Great Reform Act 1832 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Great Reform Act 1832 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background and passage of the act

- Great Reform Act 1832

- Effect of the act

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Great Reform Act 1832!

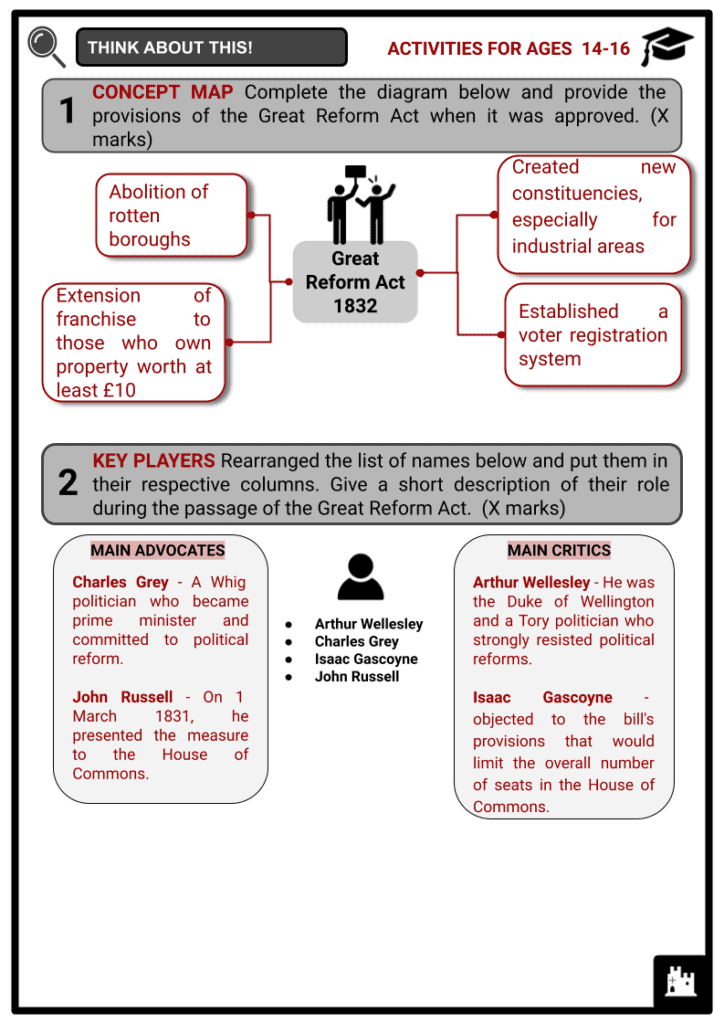

The Representation of the People Act 1832, often known as the Great Reform Act or the First Reform Bill, was the result of a lengthy public and parliamentary campaign. It was a bill passed by Parliament that altered the British electoral system and effectively gave middle-class men the right to vote, rectify the uneven distribution of seats, and abolish rotten boroughs. However, these changes accomplished little for the working class. Approximately 90% of the British people still lacked the right to vote (including all women).

Background and passage of the act

- During the reign of Henry VI, laws enacted in 1430 and 1432 standardised the property requirements for county voters. Under these acts, all owners of freehold property or land in a given county valued at least 40 shillings were eligible to vote in that county.

- This criterion, known as the 40 shilling freehold, was never updated for inflation in land value, so the quantity of land a person needed to possess in order to vote decreased over time.

- The right to vote was confined to men by tradition rather than by law.

- In the 19th century, Parliament was not representative of the population. To be eligible to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes, which disenfranchised the majority of the working class. This meant the vast majority of citizens were not eligible to vote.

- The system was very uneven and severely limited the right to vote: it failed to account for demographic movements and the rise of a new social class that accompanied the Industrial Revolution.

- Only roughly 435,000 individuals out of a population of over 24 million in the British Isles, including Ireland, were eligible to vote.

- There were constituencies with numerous voters that elected two representatives to the House of Commons.

- Pocket boroughs, owned by the Crown or big landholders, and rotten boroughs, whose populations had dwindled, were well represented, such as Old Sarum in Salisbury. Yet, major industrial towns like Birmingham and Manchester, which had risen during the previous 80 years, had no representatives in Parliament.

- Rotten boroughs electoral districts with very small populations. Old Sarum had two Members of Parliament but only seven voters.

- Pocket boroughs electoral districts where representatives were chosen by noble landowners. Numerous electorates, particularly those with tiny populations, were governed by wealthy landowners and were referred to as ‘pocket boroughs’ because they were thought to be in the pockets of their patrons.

- The majority of patrons were noblemen or landed gentry who used their local power, status and fortune to sway votes.

- The selling of the seats increased, the absence of a secret ballot enabled campaigners to exert pressure on voters, and corruption became rampant.

- At the time, the majority of those in authority were rich landowners. They passed legislation in parliament that protected their own interests, such as the Corn Laws, which prohibited the importation of inexpensive corn into the United Kingdom. This kept food prices high, so landowners profited greatly from their large farms.

- The cries for change began long before 1832, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. People tried to change this antiquated system in many different ways, such as through public gatherings, riots and pamphlets to express their opinions.

The Peterloo Massacre in St Peter’s Fields in August 1819. - In Britain, one of the most notorious protests occurred in Manchester in 1819, when a peaceful demonstration was disrupted and individuals were killed and injured. This became known as the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. This incident fuelled some of the key groups that advocated for reform.

- Public outrage against the ‘rotten’ election system reached a tipping point in 1830, prompting government action out of fear of a revolutionary revolt similar to what had just occurred in France.

- An important component in all of these events was the expansion of print, such as newspapers, and the rise of literacy among the lower classes. These factors enabled and accelerated the spread of radical ideas and information.

First Reform Bill

- The Tories were the dominant party in the House of Commons from 1770 until 1830. They were highly opposed to expanding the voting population.

- Various pro-reform ‘political unions’ consisting of middle class and working class citizens were created. The Birmingham Political Union, led by Thomas Attwood, was the most famous of them. A vital campaign topic that had been brought up often during the previous legislative session was electoral reform.

- The Tories won the election, but the support for the prime minister, Arthur Wellesley (the Duke of Wellington), was weakened. When the opposition addressed the question of reform, the Duke offered an aggressive defence of the present system of governance.

- On 15 November 1830, less than two weeks after making the statements, Wellington was forced to step down.

- In November 1830, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, a Whig, was elected prime minister. He pledged for a parliamentary reform.

- The First Reform Bill was drafted by the then prime minister Charles Grey, and brought into the House of Commons by John Russell on 1 March 1831. It passed by a single vote but Isaac Gascoyne objected to the bill’s provisions that would limit the overall number of seats in the House of Commons, and the bill eventually failed in the House of Lords.

- A bicameral parliament is comprised of two distinct assemblies that have to agree fully in order to pass new legislation. The British Parliament is bicameral because both the House of Commons and the House of Lords participate in lawmaking.

- Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington (1769–1852). Wellington was a skilled military leader who led the British and Allied troops to victory at the Battle of Waterloo against Napoleon in 1815. He was a Tory politician who resisted political reforms. He acted as prime minister from 1828 to 1830 and briefly in 1834.

- Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey (1764–1845). A rich landowner and a senior member of the Whig party who was in favour of political reform. He served as prime minister from 1830 to 1834. His cabinet approved the Great Reform Act 1832 and started the process of eliminating slavery in the British Empire.

- John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (1792–1868). Russell was a British leader who identified as a Whig and a Liberal. He held the office of prime minister twice. He was a principal leader in the campaign for the Reform Act 1832 after advocating for more than ten years in favour of parliamentary reform. He was one of the four people Grey designated to the committee to draft the reform bill.

- Isaac Gascoyne (1763–1841). Gascoyne was an officer in the British Army and a Tory politician. The third son of Bamber Gascoyne and Mary Green, he was born in Barking, London, and educated at Felsted School. He used his position to vehemently resist the abolition of the Slave Trade and the Reform Act of 1832. In addition, he opposed both the prohibition of bullfighting and Catholic Emancipation.

Second Reform Bill

- In July 1831, the Reform Bill was reintroduced to the House of Commons, gained an overwhelming majority in the 1831 general election and was approved for the second reading.

- During the committee stage, opponents of the law stalled its progress with lengthy discussions of its specifics, but it was ultimately passed by a margin of more than 100 votes in September 1831.

- The bill was then presented to the House of Lords, whose majority was known to be oppositional. After a series of discussions, when the Lords voted on the bill’s second reading, numerous Tory peers abstained from voting.

- However, the Lords Spiritual assembled in an unusually high number, and of the 22 Lords Spiritual present, 21 opposed the bill. It failed by 41 votes on 8 October 1831. The Lords Spiritual are Church of England bishops who serve in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom.

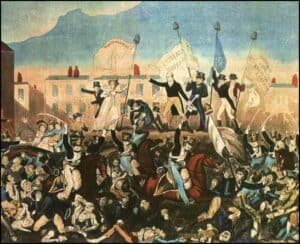

Images depicting a warehouse burned down and guards trying to subdue the riot. - When citizens received the news, reform riots broke out in various British towns, with the most severe occurring in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city’s jails were torched. In London, the residences held by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the measure in the Lords were attacked. The Bristol riots of 1831 occurred between 29 and 31 October 1831, and were part of the 1831 reform riots in England. The riots broke out after the House of Lords rejected the Second Reform Bill, delaying electoral reform attempts.

Third Reform Bill

- In December 1831, the Third Reform Act was introduced. Grey and Henry Brougham met with the new king, William IV, on 7 May 1832 and requested that he establish a large number of Whig peers in order to pass the Reform Bill in the House of Lords.

- William IV questioned the rationality of legislative change and refused to support it.

- The government of Lord Grey resigned, and the King invited the head of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to establish a new administration.

- Some protesters called for not paying taxes and a run on the banks. One day, signs popped up all over London that said, ‘Stop the Duke; go for gold!’.

- Wellington attempted to create a new government, but some Tories, notably Sir Robert Peel, refused to join a government that opposed the sentiments of the large majority of British citizens.

- The period that followed became known as the ‘Days of May’ because of the intense level of political agitation, which caused some to fear a revolution. The Days of May were a period of social unrest and political tension in the United Kingdom in May 1832, after the Tories opposed the Third Reform Bill in the House of Lords, which sought to extend parliamentary representation to the middle and working classes.

Image depicting a Birmingham Political Union meeting held in May 1832. - Lord Grey requested once more that the monarch establish a large number of new Whig Lords.

- William consented to do so, and upon hearing the news, the House of Lords decided to pass the Reform Act as a result of public pressure.

- The bill ultimately obtained royal assent on 7 June 1832, making it a law.

Reform Act 1832

- In reaction to the riots, the Reform Act of 1832 was approved by Parliament.

- It expanded the property requirements for franchise eligibility in the counties to allow male small landowners, tenant farmers, and merchants who own property worth at least £10 per year. It expanded voting rights to males of the middle class.

- Abolition of the seats: It disenfranchised 56 rotten and pocket boroughs of their seats in the House of Commons.

- New industrial areas such as Birmingham gained seats for Members of Parliament to more accurately represent the population.

- The act also established a voter registration system, which was to be managed by overseers of the poor in each parish and township to avoid voting fraud.

- As a voter was defined under the act as a male person, another change brought about by the 1832 Reform Act was the statutory prohibition of women from voting in Parliamentary elections.

Effect of the Act

- Although there had been some progress, many felt it had not gone far enough. The property requirements meant that most working men were still unable to vote. But since change had been demonstrated to be feasible, calls for additional legislative reform persisted throughout the ensuing decades.

- A few rotten boroughs, such as Totnes in Devon and Midhurst in Sussex, remained. Additionally, voting bribing remained a concern. As Sir Thomas Erskine May said, ‘it became too apparent too quickly that as more votes were generated, more votes would be sold’.

- The Reform Act did not grant voting rights to the working class. Consequently, the bond between the working class and the middle class was severed. The expansion of the Chartist Movement was a result of the 1832 Reform Act’s inability to expand the franchise beyond property-owning males.

- Chartism was the first most significant national British movement from 1838 to 1848, led by the working class calling for democracy and to expand their voting privileges. It grew due to political disappointments, economic difficulties, and the failure of the 1832 Reform Act.

- The agitation for greater change by Chartists and others had no result. However, it paved the way for subsequent reforms, such as the Second Reform of 1867 and the Third Reform of 1884.