Irish Potato Famine Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Irish Potato Famine to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Ireland in the 1800s

- Arrival of potato blight

- Government response to the famine

- Impact of the famine

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Irish Potato Famine!

Occurring from 1845 to 1852, the Irish Potato Famine was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland due to crop failures caused by potato blight. Absentee landlordism, widespread potato dependency and a heavy reliance on a single variety of potato in Ireland contributed to the outbreak of famine. Consecutive responses of the Conservative and Liberal British governments to the crisis in Ireland were unsatisfactory. The famine resulted in the deaths of about a million people, mass emigration, a significant population decline in Ireland and crucial changes in land ownership.

Ireland in the 1800s

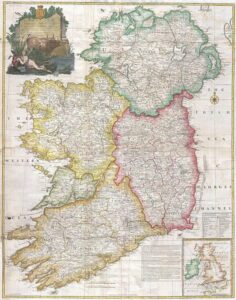

- With the ratification of the Acts of Union in January 1801, Ireland had been effectively a colony of Great Britain. The British government appointed Ireland’s executive heads of state, known respectively as the Lord Lieutenant and the Chief Secretary of Ireland. Ireland sent 105 members of Parliament to the House of Commons and 28 peers, who were titled landowners, to the House of Lords. The majority of these elected representatives were landowners or sons of landowners of British origin.

- Ireland during this period was an agricultural nation. The bulk of the Irish countryside was owned by an English and Anglo-Irish hereditary ruling class. Many were absentee landlords who were mainly Protestant.

- Large tracts of land on the various estates were rented by Protestant middlemen throughout Ireland. They then divided the land into smaller holdings, which they subsequently rented to poor Catholic farmers.

- The middleman system was a major source of discontent for tenant farmers as middlemen continued to divide estates into smaller and smaller parts while raising the rent yearly.

- The tenant farmers usually permitted landless labourers known as cottiers to reside on their farms in order to help with the annual harvest and carry out daily errands. In return, cottiers were allowed to build a tiny cabin and keep their own potato farm to feed their family.

- Some cottiers rented small fertilised potato plots from farmers as conacre, with a percentage of their potato harvest given up as payment of rent.

- More than anyone else, poor Irish labourers developed a complete dependence on the potato for survival. They also endured constant unease because of the impending risk that they might be thrown off their plot.

- Potatoes were likely first cultivated in the Andes mountains of Peru, South America. They were carried back to Europe by the Spanish, eventually reaching England.

- They were brought to Ireland in the late 16th century and farmers immediately discovered they flourished in their country’s cool, damp soil with little work.

- Potato had replaced other crops as the main source of food in the poorest regions by the 1800s. Almost three million Irish peasants lived primarily off the crop.

- Furthermore, the cottier system was developed in large part thanks to potatoes, which also supported very inexpensive labour at the expense of lower living standards.

A 1794 map of Ireland

Arrival of potato blight

- It remains uncertain how and when the strain of the water mould Phytophthora infestans, commonly known as blight, arrived in Europe. The pathogen is believed to have originated in the Toluca Valley in Mexico, spreading first within North America and then to Europe. It most likely arrived in Ireland in 1844.

Why did the emergence of P infestans have such devastating effects in Ireland and in similar areas of Europe?

- The widespread dependency on potatoes, which was not witnessed in any other country in Europe

- A disproportionate share of the potatoes grown in Ireland were of a single variety, the Irish Lumper

Timeline of potato blight and the resulting famine

- In 1844, Irish newspapers reported a disease that had attacked the potato crops in America for two years. It was during this time that ships from Baltimore, Philadelphia or New York City had accidentally carried diseased potatoes to European ports.

- The pathogen was transported to Belgium in a cargo of apparently healthy potatoes. In the summer of 1845, it revived and reproduced, devastating the potato crop in Flanders, Normandy, Holland and southern England.

- By August 1845, The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Horticultural Gazette reported about the blight on the Isle of Wight. At the same time, the blight was recorded at the Dublin Botanical Gardens, and a week later, a total failure of the crop was reported in County Fermanagh.

- In September, a couple of newspapers confirmed the presence of the blight in Ireland. Once introduced to the country, the blight spread rapidly and the potatoes themselves were rendered inedible. Crop loss in 1845 has been estimated at anywhere from one-third to as high as one-half. This plunged the rural poor into a crisis, causing great hardship.

- In 1846, the destruction of the potato crop was as rapid as it was comprehensive. Three-quarters of the harvest was lost to blight and very few healthy potatoes were harvested that autumn. As a consequence, this year marked the beginning of mass starvation and death, made even worse by an unusually cold winter. Typhus and dysentery, which took hold among malnourished and weakened people, caused more deaths.

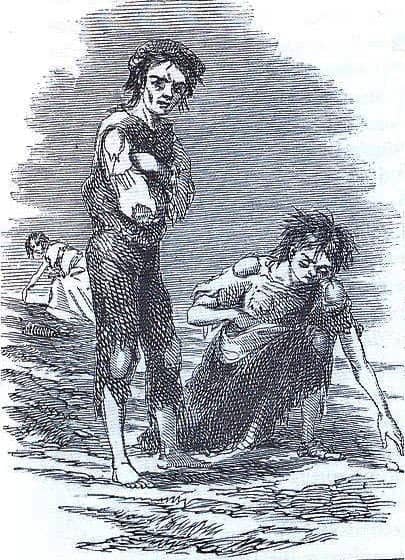

A depiction of a mother and children during the famine - In 1847, although the potato crop did not fail, seed potatoes were scarce. Many potato farmers had either not sown seeds in expectation of potato crop failure, did not have any more seeds or had been evicted for failure to pay rent. Hardly any potatoes were harvested as a result and hunger continued. This year, often referred to as Black ‘47, marked the worst point of the famine owing to the mass death and evictions.

- In 1848, potato crop yields were poor again, amounting to only two-thirds of a normal yield. Mass evictions continued with many cruel landlords taking the opportunity to remove unprofitable tenant farmers and labourers from their estates in order to replace them in many cases with livestock. Eviction often meant not only the ejection of tenants but also the burning of their cabins to prevent their reoccupation. In the same year, a radical Young Ireland group attempted an armed rebellion against the British rule, known as the Young Irelander Rebellion, but were unsuccessful.

- The potato crop picked up in the years afterwards, resulting in a gradual decline in famine deaths by about 1851.

Government response to the famine

- The British government in Dublin was overwhelmed by the famine crisis of the years 1845–1852 and their efforts to relieve the famine appeared to be inadequate.

What were the relief efforts during the famine?

Conservative government

- Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel proceeded to permit grain exports from Ireland to Great Britain. In early 1845 and 1846, he made an effort to provide relief to the famine.

- He authorised the import of maize and cornmeal from the United States, which helped avoid some starvation despite the initial unpopularity of such food.

- By 1846, the famine situation worsened, and the repeal of the Corn Laws in that year did little to help the starving Irish.

Liberal government

- Prime Minister Lord John Russell replaced Peel in June 1846 and maintained his predecessor’s policy regarding grain exports from Ireland.

- He then took a laissez-faire approach to the plight of the Irish, believing that the market would provide the food needed.

- The government’s food aid and relief works became limited, leaving many hundreds of thousands of people without access to work, money or food.

- Realising that the laissez-faire approach was inefficient, the government turned to a mixture of indoor and outdoor direct relief with a reliance on Irish resources. Indoor direct relief was administered in workhouses through the Irish Poor Laws while outdoor direct relief was provided through the soup kitchens.

- In June 1847, the government decided not to use any more central funds to alleviate famine in Ireland, putting much of the financial burden of providing for the starving Irish peasantry upon the Irish landowners. Consequently, many landlords avoided paying poor relief, which had a calamitous impact on the famine.

- By August 1847, as many as three million people received rations at soup kitchens.

Response of the military

- Being ordered in January 1846 to assist distressed regions, the Royal Navy squadron stationed in Cork undertook a significant relief operation from 1846 to 1847, transporting government relief into the port of Cork and other ports along the Irish coast.

- They also distributed supplies from the British Relief Association and treated them identically to government aid. Some naval officers supervised the logistics of relief operations further inland from Cork.

- Moreover, Royal Navy surgeons were sent to the island to help with proper, hygienic burials for the deceased and to distribute medicines that were in short supply. They also provided medical care for those suffering from famine-related illnesses.

- However, these efforts were inadequate at preventing mass death from famine and disease.

Impact of the famine

- The famine of 1845–1852 was a defining moment in the history of Ireland and its effects permanently changed the country’s demographic, political, and cultural landscape.

- About one million people died from starvation or from typhus and other famine-related diseases. The majority of the deaths were overwhelmingly from the rural poor.

- About 1.5 million people fled from Ireland, mostly to North America. Mass migration continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

- The population of Ireland continued to decline in the following decades due to overseas emigration and lower birth rates.

- The western and southwestern counties saw an exceptionally sharp decline in the number of agricultural labourers and smallholders.

- The removal of numerous smallholders from their land and the concentration of land ownership in fewer hands were further effects of the famine.

- More land was then used than before for the grazing of sheep and cattle, providing animal products for export to Britain.

- The Irish Potato Famine created a long-lasting legacy of deep resentment and mistrust towards the British. Many Irish people believed that British colonial actions directly caused the famine.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/97/Skibbereen_by_James_Mahony%2C_1847.JPG?20130122145100

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/1794_Rocque_Wall_Map_of_Ireland_-_Geographicus_-_Ireland2-rocque-1794.jpg/472px-1794_Rocque_Wall_Map_of_Ireland_-_Geographicus_-_Ireland2-rocque-1794.jpg?20110323042200

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Irish_potato_famine_Bridget_O%27Donnel.jpg/413px-Irish_potato_famine_Bridget_O%27Donnel.jpg?20050121080901