Download Mary Seacole Worksheets

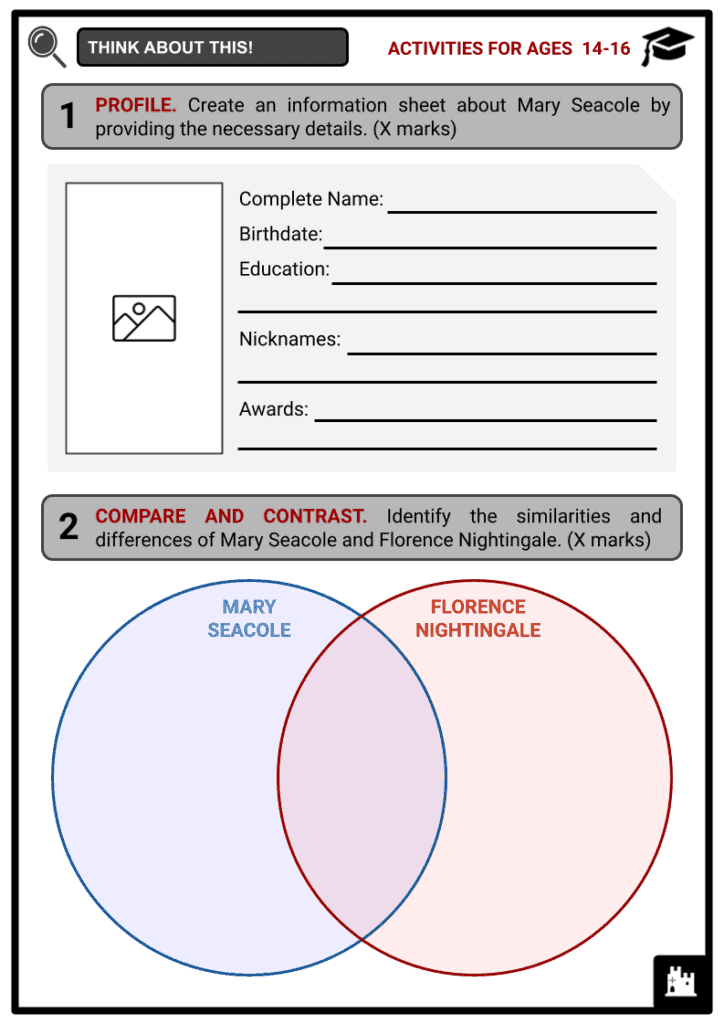

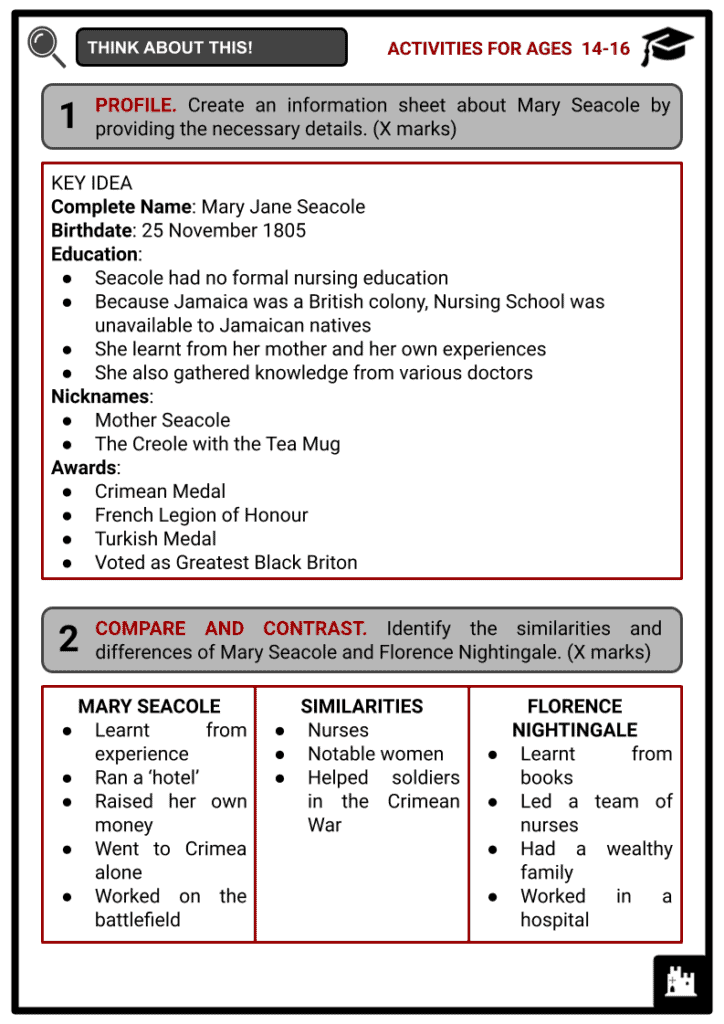

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Mary Seacole to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Early life of Mary Jane Seacole

- Travels from the Caribbean to Panama and England

- Seacole’s similarity to Florence Nightingale

- Legacy and recognition

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Mary Seacole!

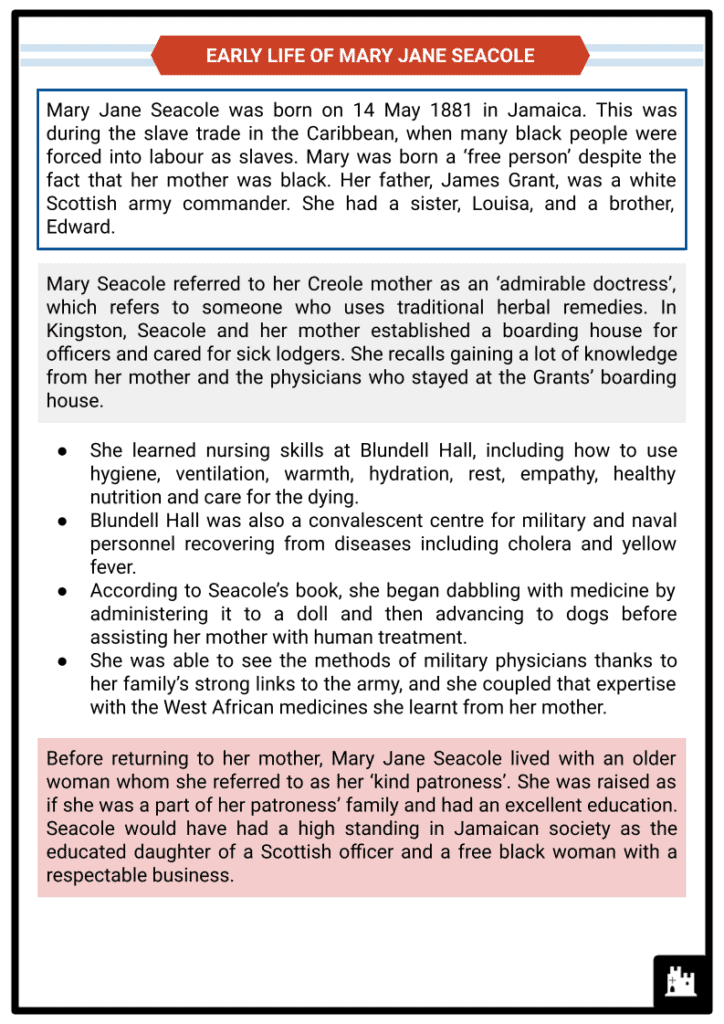

- Mary Jane Seacole, a British-Jamaican nurse and entrepreneur, established the ‘British Hotel’ behind the lines during the Crimean War. She relied on her skills and expertise as a healer and female doctor from Jamaica. Seacole was posthumously awarded the Order of Merit by the Jamaican government and hailed as the greatest black Briton in the United Kingdom.

- Mary Jane Seacole’s accomplishments as a mixed-race woman in the 19th century were absolutely exceptional. She defied societal norms and prejudices to travel the world, operate enterprises and assist those in need, even in the most dangerous places.

EARLY LIFE OF MARY JANE SEACOLE

- Mary Jane Seacole was born on 14 May 1881 in Jamaica. This was during the slave trade in the Caribbean, when many black people were forced into labour as slaves. Mary was born a ‘free person’ despite the fact that her mother was black. Her father, James Grant, was a white Scottish army commander. She had a sister, Louisa, and a brother, Edward.

- Mary Seacole referred to her Creole mother as an ‘admirable doctress’, which refers to someone who uses traditional herbal remedies. In Kingston, Seacole and her mother established a boarding house for officers and cared for sick lodgers. She recalls gaining a lot of knowledge from her mother and the physicians who stayed at the Grants’ boarding house.

- She learned nursing skills at Blundell Hall, including how to use hygiene, ventilation, warmth, hydration, rest, empathy, healthy nutrition and care for the dying.

- Blundell Hall was also a convalescent centre for military and naval personnel recovering from diseases including cholera and yellow fever.

- According to Seacole’s book, she began dabbling with medicine by administering it to a doll and then advancing to dogs before assisting her mother with human treatment.

- She was able to see the methods of military physicians thanks to her family’s strong links to the army, and she coupled that expertise with the West African medicines she learnt from her mother.

- Before returning to her mother, Mary Jane Seacole lived with an older woman whom she referred to as her ‘kind patroness’. She was raised as if she was a part of her patroness’ family and had an excellent education. Seacole would have had a high standing in Jamaican society as the educated daughter of a Scottish officer and a free black woman with a respectable business.

TRAVELS FROM THE CARIBBEAN TO PANAMA AND ENGLAND

- Mary Seacole then worked with her mother, providing nursing help in the British Army hospital at Up-Park Camp on occasion. She also visited the British colony of Fledgling Providence in the Bahamas, the Spanish province of Cuba and the new Republic of Haiti in the Caribbean. Seacole recorded these travels, but excluded any mention of significant events, such as the Christmas Rebellion in Jamaica of 1831, the abolition of slavery in 1833 and the abolition of ‘apprenticeship’ in 1838.

- On 10 November 1836, Mary Jane Seacole married Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston. Edwin was a trader who appeared to be of weak constitution. The newlyweds relocated to Black River and opened a grocery business, which failed to thrive. In the early 1840s, they returned to Blundell Hall.

- She had a slew of personal tragedies between 1843 and 1844. On 29 August 1843, a fire in Kingston destroyed much of the boarding house, and she and her family were forced to leave. Blundell Hall was destroyed, and New Blundell Hall was built in its stead. In October 1844, her husband died, followed by her mother.

- In 1850, she was a nurse who cared for cholera patients in Kingston. Then in 1851, she travelled to Panama, only to discover that her abilities were required once more since the town of Cruces was experiencing its own epidemic of the illness. Mary claims to have saved her first cholera patients in Cruces by employing mustard emetics to induce vomiting, heated cloths to battle chills, mustard plasters on the stomach and back, and Calomel in high dosages at first, then in lower amounts. She returned to Kingston in 1853 to help victims of the yellow fever epidemic.

- Medical authorities asked her to administer nursing services at Up-Park, the British Army’s headquarters in Kingston, and she reorganised New Blundell Hall, her mother’s old lodging house that had been rebuilt following a fire, to serve as a hospital.

- Mary didn’t have any children of her own, but the deep maternal bonds she built with these troops, as well as her affections for them, would eventually lead her to the Crimea.

- European and Asian nations both valued Crimea as a strategic location. The overland routes to India were under the power of whoever controlled the Crimean Peninsula. In March 1854, Britain and France declared war on Russia in support of the Ottoman Empire.

- Even though Mary Jane Seacole saw regiments she knew leave, she decided to return to Panama to wind up her business. Seacole flew to London in the autumn of 1854 to deal with her losing gold stock market investments. Advertisements for hospital nurses needed in the Crimea were printed in local newspapers, but Mary Seacole did not apply.

- Mary Seacole’s race may have been a factor in her ability to obtain a nursing position in the Crimea, but this is not certain. Seacole never identified as a black person. Other considerations worked against her: she had never applied formally, had no hospital experience, and was beyond the age limit for nursing.

- She opted to create a company instead of continuing her nursing career. Thomas Day, a relative of her husband’s, was her business partner. She knew him from Panama and ran into him again in London. She landed in Turkey in March 1855, many months after the major battles.

SEACOLE’S SIMILARITY TO FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE

- Between Sevastopol and Balaclava in Crimea, Mary Jane Seacole established her British Hotel, which she named Spring Hill. The British Hotel was not a hotel in the modern sense of the word. While Seacole’s original plan was to create “a mess table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers”, she instead built a hut that operated as an all-in-one shop-restaurant for officers, as well as a ‘canteen’ for regular troops.

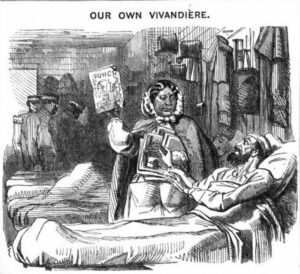

- She stayed on board a ship in Sevastopol’s harbour while waiting for her ‘tumble-down hut’ to be ready, serving hot tea, cake and lemonade to soldiers on the wharf waiting transit to the general hospitals. The weather was really cold, and the gesture was greatly appreciated.

- Part of her business was to provide beverages to battle audiences. She did this three times, then returned to the battlefield after the fighting had ended to help the injured and, on rare instances, to console the dying. Following the fall of Sevastopol, Seacole’s company flourished. There were no further fights at this time, although the peace treaty was still being negotiated.

- Mary Jane Seacole’s work as a nurse was almost as well-known as Florence Nightingale’s, and newspapers dubbed both women ‘The Mother of the Army’, with Florence Nightingale being dubbed ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ and Mary Seacole being dubbed ‘The Creole with the Tea Mug’.

- It was the wine that earned Seacole a few notable enemies in her line of work, chief among them Nightingale. Serving wine to troops was against Victorian customs, and the fact that it was being provided by a woman of colour sparked moral anger among Victorians.

- Nonetheless, the men adored Seacole, especially one Christmas when she found enough ingredients to create multiple plum puddings, a typical English holiday delicacy, for the soldiers and commanders. Many wrote lovingly of her care in letters back home, calling her ‘Aunty’ or ‘Mother Seacole’.

LEGACY AND RECOGNITION

- Mary Jane Seacole died on 25 November 1805 in her house at 3 Cambridge Street (later renamed Kendal Street) in Paddington, London; the cause of death was ‘apoplexy’. Seacole was well-known near the end of her life, but she quickly faded from public memory in the United Kingdom. However, there has been a rebirth of interest in her and efforts to recognise her accomplishments in recent years.

- In the 1950s, she was better remembered in Jamaica, where she had significant buildings named after her: the headquarters of the Jamaican General Trained Nurses’ Association was christened ‘Mary Seacole House’, followed by the naming of a hall of residence at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica, and a ward at Kingston Public Hospital. Seacole was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1990, more than a century after her death.

- The centenary of her death was celebrated with a memorial service on 14 May 1981 and her grave is maintained by the Mary Seacole Memorial Association, an organisation founded in 1980 by Jamaican-British Auxiliary Territorial Service corporal, Connie Mark.

- The Greater London Council placed an English Heritage blue plaque at her home in 157 George Street, Westminster, on 9 March 1985, but it was removed in 1998 before the site was renovated. On 11 October 2005, a green plaque was positioned at 147 George Street in Westminster. However, at 14 Soho Square, where she lived in 1857, a new blue plaque has been installed.