Peterloo Massacre Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Peterloo Massacre to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- The Day of the Peterloo Massacre

- Aftermath of the Massacre

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Peterloo Massacre !

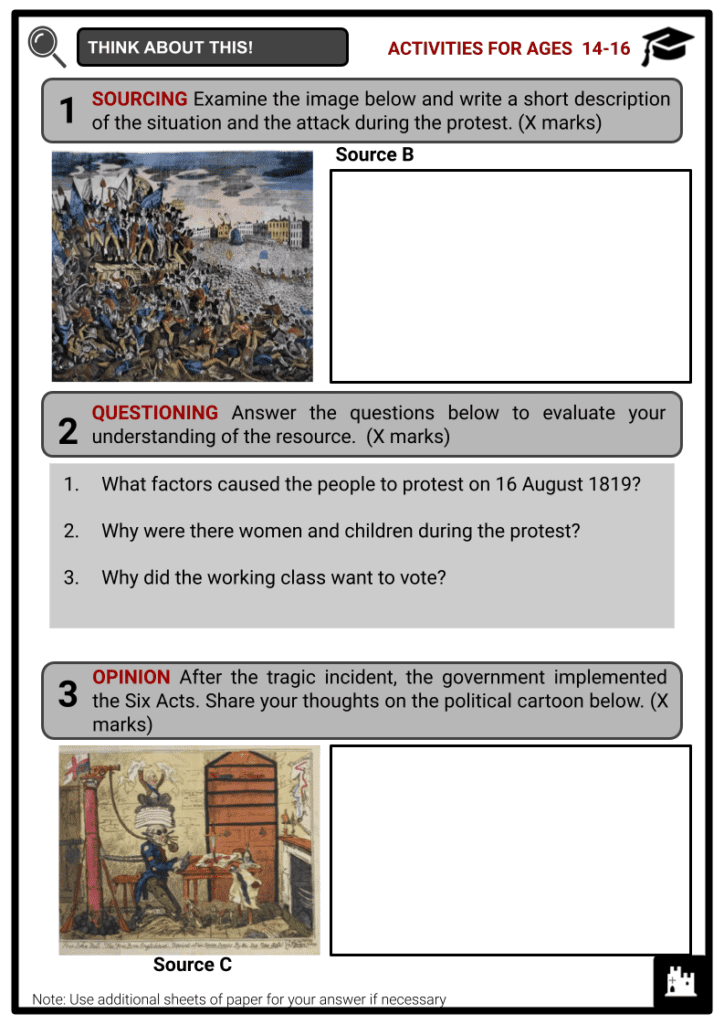

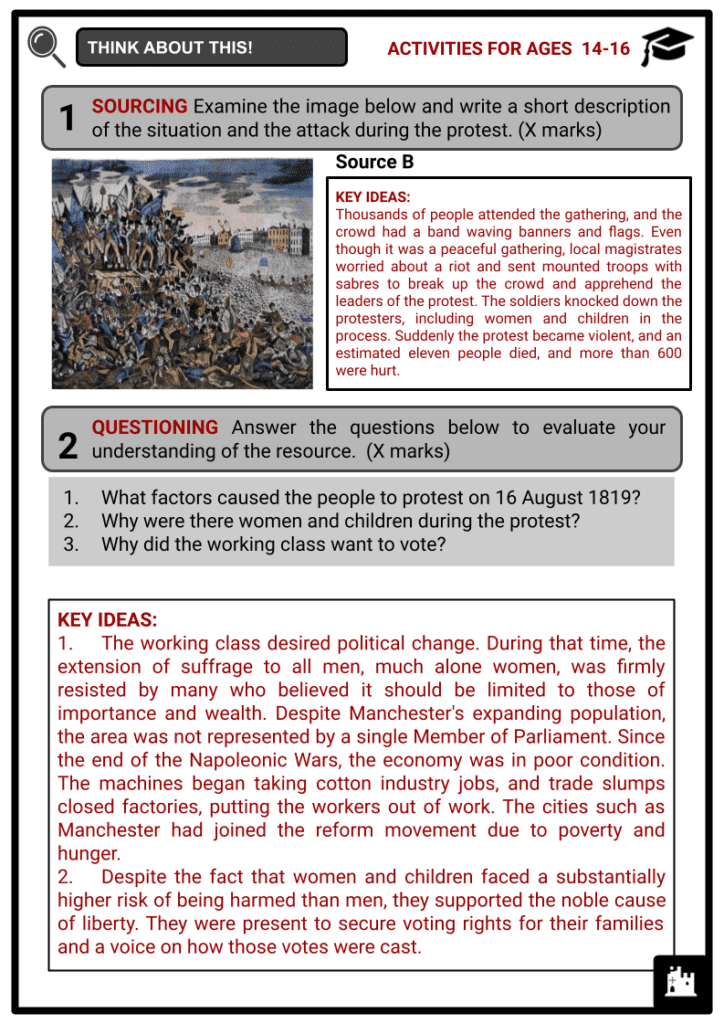

In the early 19th century, only wealthy men who owned property were allowed to vote in elections. The working-class people were unhappy with the lack of representation in Parliament. An estimated 60,000 people gathered at St. Peter's Fields on 16 August 1819, carrying banners with slogans supporting political reform. Their primary demand was a voice in Parliament. The peaceful protest turned violent when magistrates in Manchester ordered a private militia funded by wealthy locals to charge the crowd with sabres. An estimated 18 people were killed in the chaos, and over 650 were injured. The tragic incident was known as the Peterloo Massacre in British history.

Background

- In 1819, a year marked by industrial downturn and rising food costs, a series of political protests culminated in the August gathering of political radicals.

Economic Strife after the Napoleonic War

- The reinforcements during the Napoleonic War came at a great cost, and taxes were hiked to pay for the war effort. Due to high taxes, soaring food prices, unemployment induced by wartime trade restrictions, and the increased use of labour-saving machines, many British men and women were left in absolute poverty.

- The cotton and wool textile industrialists who reduced wages without providing relief attributed their actions to market forces caused by the aftershocks of the Napoleonic War.

- The end of the Napoleonic War in 1815 brought famine, and many people were unemployed due to a severe economic downturn. This was made worse when the first of the Corn Laws Laws passed.

- Under the Corn Laws, the United Kingdom implemented tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn between 1815 and 1846.

- The Corn Laws prevented the import of affordable corn, initially by restricting imports below a specific price and later by imposing high import charges, making it costly to import from overseas, even when food supplies were few.

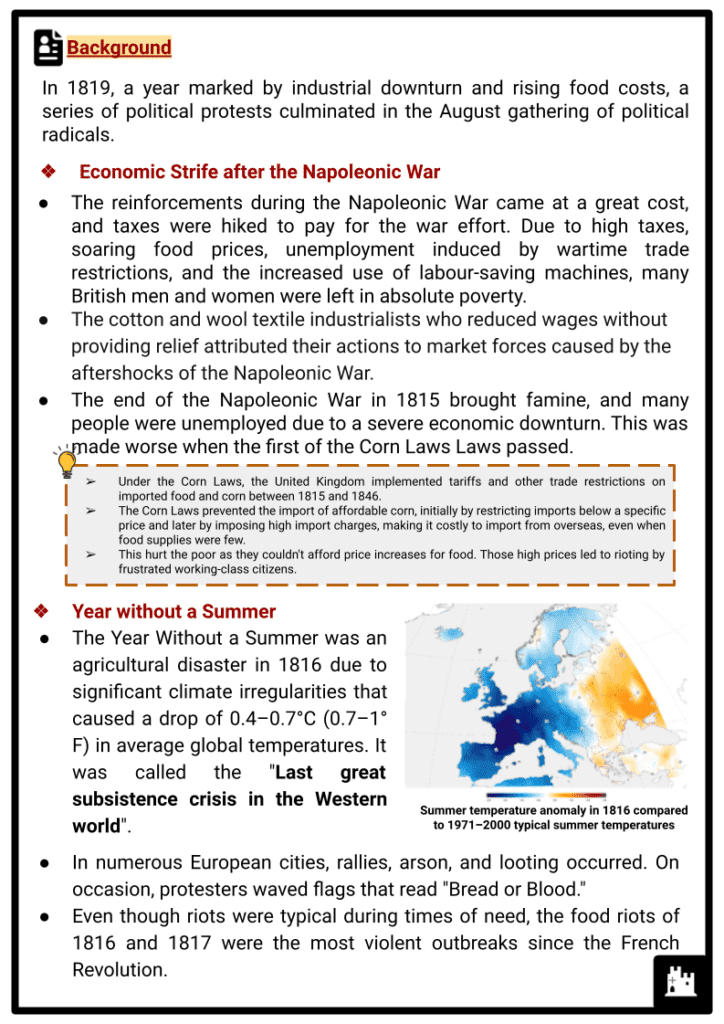

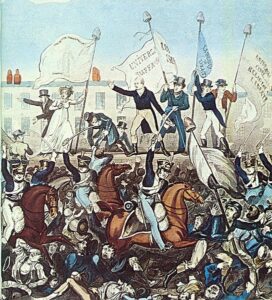

Summer temperature anomaly in 1816 compared to 1971–2000 typical summer temperatures - This hurt the poor as they couldn't afford price increases for food. Those high prices led to rioting by frustrated working-class citizens.

Year without a Summer

- The Year Without a Summer was an agricultural disaster in 1816 due to significant climate irregularities that caused a drop of 0.4–0.7°C (0.7–1°F) in average global temperatures. It was called the "Last great subsistence crisis in the Western world".

- In numerous European cities, rallies, arson, and looting occurred. On occasion, protesters waved flags that read "Bread or Blood."

- Even though riots were typical during times of need, the food riots of 1816 and 1817 were the most violent outbreaks since the French Revolution.

Rotten boroughs and political corruption

- A rotten borough was a town sending representatives to Parliament, describing constituencies maintained by the crown or an aristocratic patron to control House of Commons seats.

- A member of Parliament from a rotten borough was usually appointed by the landlords.

- The term rotten had the connotation of corruption because of the lack of a secret ballot and their dependence on the borough's "owner," most or all of the few electors in such boroughs were unable to vote as they liked. Hence, it was easy for candidates to buy their way to victory.

Suffrage

- Only extremely rich men who owned property were permitted to vote at the time. This meant that less than 5% of the population had a say in how the nation was governed.

- In addition, many common people were dissatisfied with the lack of representation in Parliament. Manchester and Salford, for instance, each had a population of over 150,000 people yet lacked their own representative in Parliament.

Radical meetings

- During 1816–1817, the House of Commons rejected numerous reform petitions, the greatest of which was from Manchester, with over 30,000 signatories.

- On 10 March 1817, a mass of 5,000 assembled at St. Peter's Fields to send a portion of their number to march to London to petition the Prince Regent to urge parliament into reform; the so-called "Blanket March”, named for the blankets the protesters (Blanketeers) brought to keep warm throughout the long evenings spent marching.

The Day of the Peterloo Massacre

- By the beginning of 1819, the economy was in bad shape. The factory workers had very few rights and most of them worked in appalling conditions. With no platform to air their grievances, so the calls for political reform gathered momentum.

- In March 1819, the Manchester Patriotic Union Society was formed by Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe from the Manchester Observer newspaper. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined to support the organisation.

Manchester Observer Newspaper - The Manchester Observer was a radical provincial newspaper with a national impact formed by a group of radicals that included John Knight, John Saxton and James Wroe. They called for the reform of the Houses of Parliament and the repeal of the Corn Laws.

- Its influence spread to the most important cities and towns in northern England, and copies were sold in Birmingham. After only a year, 4,000 copies had been sold.

- The organisation's primary purpose was to obtain parliamentary reform. They decided to invite Richard Carlile, Henry “Orator” Hunt, and Major John Cartwright to speak at a public meeting in Manchester.

The Day of the Protest

- About 60,000 people attended St Peter’s Field on 16 August 1819. Men and women with children from all over the North West, including some who walked nearly 30 miles to get there, came to the event. No one was armed, and everyone acted peacefully.

- Some people in the crowd were there just to see what was going on, but most were there because they wanted to see the main speaker, Henry Hunt, known as "Orator" Hunt because he was so good at public speaking.

- Hunt was a British radical speaker known as a pioneer of working-class radicalism and significantly influenced the ensuing Chartist movement. He pushed for the reform of parliament and the abolition of the Corn Laws.

- He was the first parliamentarian to support women's suffrage. He became known as a great speaker, and people always asked him to speak at public events.

- The protesters were dressed in their Sunday best and marched into Manchester. There was a festive atmosphere despite the seriousness of the cause.

- Alongside the procession were bands playing music and individuals dancing. In many cities, the march was practised on local moors in the weeks preceding the meeting so that everyone could come in an orderly manner.

- Their demands were straightforward: the right to vote for every man, regardless of income, annual elections, and a secret ballot so that nobody knew who voted for whom.

Suppressing the Protesters

- Although there was no trouble, the magistrates feared that such a growing crowd of reformers could result in a riot. The magistrates arranged for a substantial contingent of soldiers to be present in Manchester on the day of the meeting.

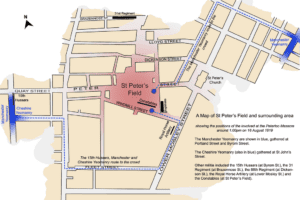

- It included four squadrons of cavalry from the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, a division of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), the Salford and Manchester Yeomanry (120 men), and all the special constables of Manchester (400 men).

The surrounding area of St. Peter’s Field on 16 August 1819. - As Hunt began his address, William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates gave the order to arrest him and the other leaders of the demonstration.

- In an attempt to follow the order, the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, a volunteer cavalry used for home defence and keeping the peace, charged into the crowd, knocking down a woman and killing a child. Henry Hunt was eventually caught.

- The 15th The King's Hussars, a mounted regiment of the regular British Army, was then called upon to disperse the protesters. With drawn sabres, they attacked the crowd, ensuing general panic and mayhem.

- Protesters who were already cramped, exhausted and overheated panicked when the soldiers rode in, and several were crushed while attempting to flee. Soldiers intentionally sliced both men and women, particularly those carrying banners and flags.

- The actual number of those injured and killed at St. Peter's Field has never been determined with certainty, as there was neither an official count nor an investigation, and many injured individuals fled to safety without reporting their injuries or seeking treatment.

- According to historians, there were 11–18 fatalities at the Battle of Peterloo, including the tragic loss of an unborn child. In addition, more than 650 people were hurt.

- A notable aspect of the event was the large number of women present at the Peterloo gathering. There were also recorded casualties of women.

- The majority of the ladies wore white, and some created all-female contingents bearing their own flags.

- They were there to support their husbands, fathers, and sons in their fight for radical parliamentary reform.

The Aftermath of the Massacre

- The incident came to be known as the "Peterloo Massacre." James Wroe, editor of Manchester Observer published the name Peterloo for the first time a few days after the massacre. The term was intended to ridicule the soldiers who attacked and killed defenceless citizens by contrasting them to the newly returning Waterloo combat heroes.

- There was tremendous public sympathy for the demonstrators' dire situation. The Times newspaper published a horrific account of the day's events, sparking wide outrage and briefly uniting supporters of a more limited reform with radical advocates of universal suffrage.

- A massive petition including 20 pages of signatures was presented, emphasising the petitioners' belief that, regardless of their stance on the reform cause, the 16 August assembly was calm until the arrival of the soldiers.

- The government ordered the police and courts to investigate the journalists, presses, and publications of the Manchester Observer.

- Wroe was arrested and charged with making a publication against the government.

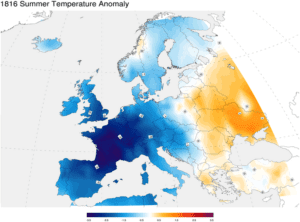

- The government had enacted the Six Acts by the end of 1819 to restrict publications and radical meetings. By the end of 1820, every prominent working-class radical reformer was in gaol.

- The law restricted the rights of free speech, assembly, and other civil liberties, increased fines for seditious libel and taxes on newspapers, expanded police access to private residences and allowed for swift trials and severe penalties for those who violated public order.

- Even though Peterloo didn't succeed in its goal of getting better political representation, it brought this issue to the public's attention and is now known as the start of the suffrage movement.

- The massacre helped to establish parliamentary democracy, particularly the Great Reform Act of 1832, which eliminated "rotten" boroughs like Old Sarum and established new parliamentary seats, mainly in the industrial towns of northern England.