Download Political Clubs Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Political Clubs to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Origins of the political clubs

- Political clubs in the French Revolution

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Political Clubs!

- Over the course of the French Revolution in the late 18th century, numerous political groups, clubs and organisations were created and grew in popularity as they were no longer subject to censorship. The political clubs started as social gatherings outside the legislatures and evolved into political parties influencing the agenda and decisions in the legislature.

Origins of Political Clubs

- They were organised, attracting ambitious men looking to advance their careers in the government. Consequently, these clubs became a vehicle for manipulating and pressuring the national government. Significant political clubs during the period include the Breton Club, Jacobins, Society of 1789, Cordeliers, Feuillants, and the Girondins.

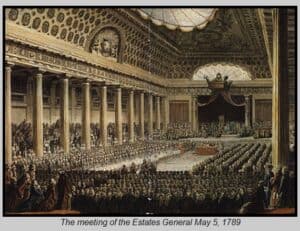

- The meeting of the Estates General at Versailles, May5, 1789. The Three Estates are seated separately, the Nobility on the left, the Clergy on the right, and the Third Estate in the rear of the hall, furthest removed from the king and ministers.

- From approximately the 15th century until 1789, the Ancien Régime was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France. Under the regime, France was an absolute monarchy with few and limited representative institutions. All rights and status flowed from the social institutions, divided into the estates of the realm: clergy, nobility, and commoners. Politics was perceived as the private business of the monarch.

- Between 1700 and 1789, the French population ballooned, resulting in the rise in unemployment, accompanied by climbing in food prices due to years of bad harvests.

- Royal authority collapsed, and widespread social distress led to the gathering of the Estates-General in May 1789, a national representative body which had not met since 1614.

- In June, the representatives of the Third Estate (commoners) of the Estates-General transformed into a National Assembly, which passed a series of radical measures, among them the abolition of feudalism, state control of the Catholic Church, and extending the right to vote.

- They declared that the Nation, not the king, was now the sovereign authority in France.

- The storming of the Bastille in Paris on 14 July prevented Louis XVI from subduing the resistance.

- The National Assembly started the immense work of reforming institutions and society and creating a new constitution for the country.

- As the censorships were lifted, political writings were distributed, and political clubs began to form to support the work of reform.

- Political clubs began as social events but were different from the salons, circles and literary associations of the 1780s. Most political clubs were formed informally but with time they were modified and became more organised and formalised.

Political clubs in the French Revolution

- Political clubs can be defined as groups formed by like-minded people who meet socially, outside of the legislatures and formal political bodies, to discuss and debate political issues and events. They played an integral part in the French Revolution from late 1789. Most clubs established their own goals, customs, procedures and membership requirements. All clubs, however, acquired a regular meeting place and members attended regularly. Some clubs behaved similarly to modern-day political parties.

Breton Club

- The Breton Club, the Revolution’s first significant political club, began as an informal gathering of Third Estate deputies at a Versailles café, before and after sessions of the Estates-General. Initially, most of these deputies were from Brittany, hence the name of the club. Their meetings involved discussions on provincial issues as well as the proceedings at the Estates-General.

- By early June, the Bretons had opened their meetings to deputies from other regions, as well as a few liberal aristocrats. Some members left the Breton Club in July, following the formation of the National Assembly, especially members not from Brittany as they felt that their mission was accomplished.

Jacobins

- The Society of the Friends of the Constitution, commonly known as the Jacobin Club, became the most radical and influential political club during the Revolution.

- It evolved from the Breton Club. The nickname Jacobins originated from the location of the club’s main convent on Rue Saint-Jacques (Jacobus in Latin). Members of this club were mostly businessmen, bankers, lawyers and other notables who could manage the high membership fees. At its height, the club reached 500,000 members. It was initially founded by anti-royalist deputies and grew into a nationwide republican movement. Its members supported the rights of property and favoured free trade and a liberal economy.

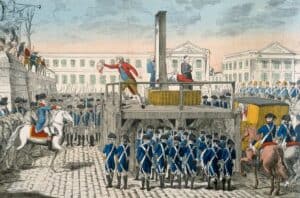

- As the Revolution progressed, they grew more extreme and radical along with the governing assemblies. By 1793, they were playing a leading role in Revolutionary government and became instruments of the Reign of Terror. The club was permanently closed in 1794.

Society of 1789

- A group of constitutional monarchists, frustrated by growing radicalism, abandoned the Jacobins to form their own group called the Society of 1789, founded in April 1790. The Society of 1789 had around 300 members, including 40 to 50 deputies from the National Constituent Assembly. Meetings of the Society were not different from social gatherings of the Parisian elite, with fine dining followed by brandy and wine, served on a balcony overlooking the Palais-Royal.

- The Jacobins regarded the Society a remnant of the privilege and elitism of the Ancien Régime. The popularity of the club eventually decreased the same year as it was founded.

Cordeliers

- The Society of the Friends of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, commonly known as the Cordeliers, was located in the Convent of the Cordeliers (another name for Franciscans).

- With its membership fees kept low, the club was open to all. With the slogan ‘Liberty, equality, fraternity’, the club was focused on grievances and criticisms and campaigned for the protection of individual rights and freedoms. It was sympathetic to the interests of the working class and served as a watchdog looking for signs of abuse of power by the men in authority.

- The club’s famous demonstration in the Champ-de-Mar, dispersed by the National Guard, resulted in casualties and in the temporary disbanding of the club. In 1794, their leaders were arrested and executed for criticising the rule of the Convention. The club consequently fell into oblivion.

Feuillants

- The Feuillants split from the Jacobins on 16 July 1791 after the flight to Varennes. They were in support of preserving the position of the king and the proposed plan of the Assembly for a constitutional monarchy. They held their meetings in a former monastery of the Feuillant monks and called themselves the Amis de la Constitution. Its members attempted to capture the Jacobins’ network of provincial affiliates, but most refused to join them.

- The club’s moderation and exclusivism made it less popular than the Jacobins. Membership rapidly declined until it disappeared when the monarchy fell in 1792.

Girondins

- The Girondins were initially part of the Jacobins. The name originated from the département of Gironde in southwest France, where the prominent members of the group came from. Unlike other political clubs, they were a group of loosely affiliated individuals. They supported the end of the monarchy but resisted the revolutionary activities. Furthermore, they were hesitant to reform and kept on delaying the execution of the king. Their conflict with the Jacobins became intense, resulting in the arrest, trial and execution of Girondins’ leaders and the first major purge of the Revolution.