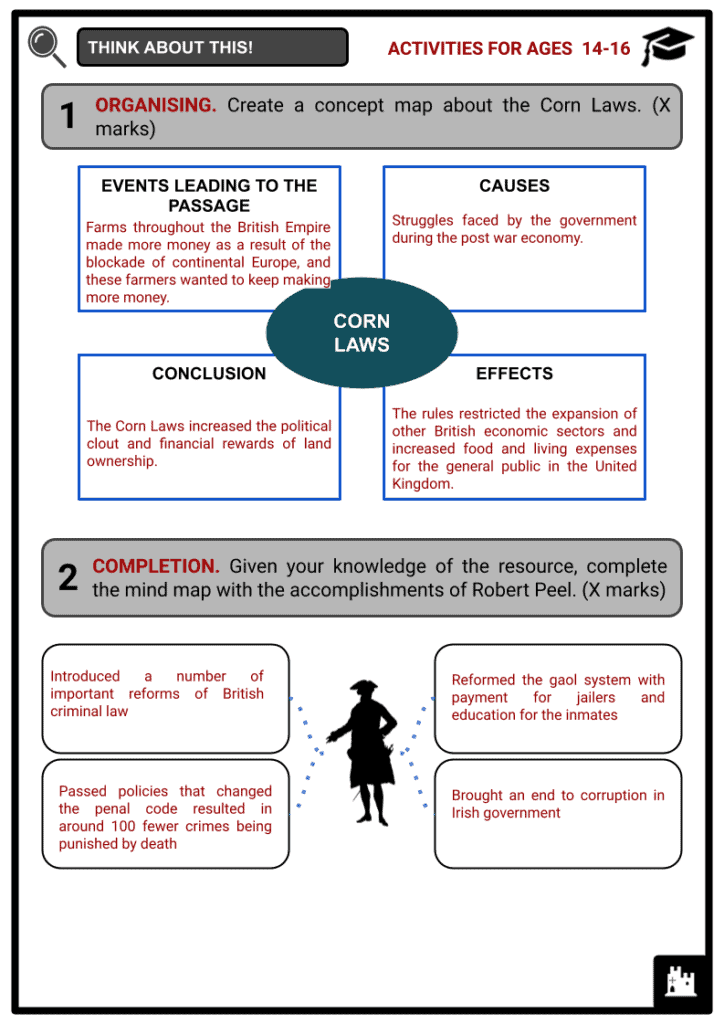

Robert Peel Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Robert Peel to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life

- Early Career

- Queen Victoria and Peel

- Peel and the Corn Laws

- Later Career and Death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Robert Peel!

From 10 December 1834 to 8 April 1835, and again from 30 August 1841 to 29 June 1846, Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, served as the Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. While serving as Home Secretary, he contributed to developing the modern police force, oversaw the creation of the Conservative Party from the remnants of the Tory Party, and repealed the Corn Laws. This regulation imposed tariffs on foreign-imported cereal grains like wheat and maise to support domestic agriculture.

EARLY LIFE

- Peel was born at Chamber Hall in Bury, Lancashire, to Sir Robert Peel, 1st Baronet, an entrepreneur and politician, and his wife Ellen Yates. His father was one of the wealthiest textile manufacturers of the early Industrial Revolution. The family relocated from Lancashire to Drayton Manor in the Staffordshire town of Tamworth; the house was later torn down, and Drayton Manor Theme Park now stands on the site.

- In Bury and Tamworth, Peel acquired his early education from a clergyman who also served as his tutor. In February 1800, he enrolled at Harrow School. Peel matriculated at Christ Church in Oxford in 1805. Charles Lloyd was his mentor and was later named Regius Professor of Divinity and Bishop of Oxford on Peel’s advice. Peel was the first Oxford student to earn a double first in mathematics and classics in 1808. As a Manchester Regiment of Militia captain in 1808, he also held military commissions. In 1809, Peel attended Lincoln’s Inn to study law.

EARLY CAREER

MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT

- At age 21, Peel entered politics as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish rotten borough of Cashel, Tipperary.

- Besides his father, Chief Secretary for Ireland, Sir Arthur Wellesley who later on became the Duke of Wellington, sponsored Peel for the election.

- In 1810, Peel became the Under-Secretary of State for War and the Colonies and worked directly with Lord Liverpool, Secretary of State. In 1812, Peel became Chief Secretary for Ireland under the government formed by Lord Liverpool.

- Insisting that Catholics could not be admitted to Parliament because they would not take the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, Peel vehemently opposed Catholic Emancipation. Peel gave the final speech opposing Henry Grattan’s Catholic Emancipation bill in May 1817; the measure was defeated by 245 votes to 221 in the House.

- To stabilise British finances following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the House of Commons established the Bullion Committee in 1819, with Peel as its chairman. The Bank Restriction Act of 1797 was intended to be repealed under Peel’s Bill in four years, which would have put British currency back on the gold standard.

HOME SECRETARY

- In 1822, Peel entered the cabinet as Home Secretary and was considered one of the vital members of the Tory party.

- He introduced significant changes to British criminal law while serving as Home Secretary. By eliminating numerous criminal acts and combining their provisions into what are now known as ‘Peel’s Acts’, he decreased the number of offences that could result in death and streamlined the law.

- Lord Liverpool became ill in 1827, and George Canning took his place. Peel left his position as Home Secretary. Canning supported Catholic Emancipation, but Peel had been one of the movement’s most vocal opponents. Four months later, Canning died. Peel returned as the Home Secretary under the premiership of Duke Wellington.

- Peel was forced to run for re-election to his Oxford seat because he represented Oxford University graduates, many of whom were Anglican clergy members, and since he had previously run on a platform opposing Catholic Emancipation.

- Peel guided the Catholic Emancipation bill through the House of Commons, while Wellington through the House of Lords. Only with the assistance of the Whigs, a political party in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, could the bill be passed because many Ultra-Tories were adamantly opposed to Catholic Emancipation.

- It was in 1829 that Peel established the Metropolitan Police Force for London, based at Scotland Yard. The Metropolitan Police Force was under the Metropolitan Police Act 1829, and on 29 September of that year, the first constables of the service appeared on the streets of London. Although initially unpopular, they were extraordinarily effective in reducing crime in London, and by 1857, other British cities were required to establish their police forces.

Satire of Peel and Wellington on extinguishing the Catholic Emancipation - The Metropolitan Police’s first set of Instructions to Police Officers, which emphasised the value of its civilian nature and police by consent, is credited to Peel, the founder of contemporary policing.

THREE CORE IDEAS OF POLICING

- “Instead of arresting criminals, the objective is to prevent crime. We don’t need to punish or repress citizens’ rights if the police prevent crime from occurring. A police force that works well doesn’t make many arrests; instead, the crime rate in the area is low.”

- “Gaining the public’s support is essential for crime prevention. Every community member must take on the same level of responsibility for crime prevention as if they were all volunteer police officers. It will If the public believes in and trusts the police, they should only take this obligation.”

- “The public supports the police because they uphold communal values. Using force only as a last resort, employing cops who represent and understand the community, and keeping the law impartially are all necessary steps in earning the public’s approval.”

NINE PRINCIPLES OF POLICING

- To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment.

- To recognise always that the power of the police to fulfil their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.

- To recognise always that to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also securing the willing cooperation of the public in the task of securing observance of laws.

- To recognise always that the extent to which the cooperation of the public can be secured diminishes proportionately the necessity of the use of physical force and compulsion for achieving police objectives.

- To seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion, but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy, and without regard to the justice or injustice of the substance of individual laws, by ready offering of individual service and friendship to all members of the public without regard to their wealth or social standing, by ready exercise of courtesy and friendly good humour, and by ready offering of individual sacrifice in protecting and preserving life.

- To use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain public cooperation to an extent necessary to secure observance of law or to restore order, and to use only the minimum degree of physical force which is necessary on any particular occasion for achieving a police objective.

- To maintain at all times a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public is the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- To recognise always the need for strict adherence to police-executive functions, and to refrain from even seeming to usurp the powers of the judiciary of avenging individuals or the State, and of authoritatively judging guilt and punishing the guilty.

- To recognise always that the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder and not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with them.

PRIME MINISTER

- After serving twice as Home Secretary (1822-1827 and 1828-1930), Robert Peel joined the opposition from 1830 to 1834 during the term of PM Charles Grey. When Parliament was dissolved in December 1834, Peel gained considerable support, but it was still insufficient to achieve a majority against the Whigs led by William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne.

- In 1835, the total number of seats in the House of Commons was 658 and 330 seats were required for a majority. In the 1832 elections, the Whigs under Melbourne won 441 seats versus Peel’s 175 seats.

- During the general election in 1834, Peel issued the Tamworth Manifesto, a political statement many historians consider the foundation of the Conservative Party. With Duke of Wellington’s endorsement, Peel became prime minister in December 1834. On 18 December, the Tamworth Manifesto was published and distributed around Britain. The manifesto appealed the following to the electorate:

- Peel’s acceptance of the 1832 Reform Act.

- A careful review of institutions, including Church reforms.

- A promise of modest reforms for the survival of the Conservatives.

- In the first 100 days of premiership, he faced severe opposition from the Whigs and Irish Radical members of Parliament. Due to a lack of majority votes, bills were repeatedly defeated. Out of frustration, Peel resigned as prime minister in 1835. With the support of the Whigs, Lord Melbourne became prime minister again, a position he held until 1841.

- In May 1839, Peel was again offered to form a government. However, like the previous years, he would lead a minority government. At the time, the newly crowned Queen Victoria was highly influenced by the Whigs and Lord Melbourne. Wives and female relatives of the Whigs populated the queen’s household. Before considering the offer of a premiership, Peel requested that the queen’s entourage be replaced with Conservatives. Despite the assurance of the Duke of Wellington, both Queen Victoria and Peel refused to compromise.

- On 20 June 1837, Victoria, daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent (the fourth son of George III) and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, inherited the throne of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. With the death of her father’s three elder brothers without any surviving heirs, 18-year-old Victoria became queen.

QUEEN VICTORIA AND PEEL

- The Bedchamber Crisis occurred on 7 May 1839, during Queen Victoria’s first change of government. After a narrow margin of five votes in the House of Commons, PM Lord Melbourne declared his intent to resign. New to her role as sovereign, Queen Victoria, a Whig sympathiser, asked the Duke of Wellington to form a government. Wellington, a Tory, politely declined. Queen Victoria then requested Conservative Peel, who also plunged due to a weak number of supporters. Peel offered a bargain which Queen Victoria refused.

- In the end, the queen retained her bedchamber ladies, whom she considered to be her friends. Meanwhile, Peel dismissed the offer of a premiership. Soon, Lord Melbourne agreed to stay on as prime minister. Following Queen Victoria’s marriage to Prince Albert in 1840, her ladies played a minimal role. By 1841, the queen replaced three of her Whig ladies with Conservatives. Many believed that the queen accepted her husband’s democratic advice.

- Despite Queen Victoria’s support to Lord Melbourne, the prime minister dissolved Parliament and called for an election. Using the Conservative’s 11-point programme, Peel won the election.

- When Peel finally gained the majority of the government, he faced economic recession and a budget deficit of £7.5 million.

- 1842. To raise revenue, Peel reintroduced the Income Tax Act. A rate of 7 pence per pound was imposed on all annual incomes over £150.

- Before 1842, income tax was introduced by PM Henry Addington in 1803. Peel’s income tax was the first imposition outside of wartime. In the same year, the House of Commons defeated an attempt to repeal the Corn Laws.

- 1844. A series of acts known as the Factory Acts were passed to regulate the conditions of industrial workers. The Factories Act of 1844 repealed the 1833 Factory Act. Also known as Graham’s Factory Act, it retained the twelve-hour day and redefined night working among young persons and women of all ages. Working hours of children (ages 9-13) were limited to 9 hours with a lunch break. Rudimentary safety standards, such as regular cleaning of factories with lime, were introduced.

- 1846. The Importation Act of 1846 repealed the Corn Laws. The abolition of the Corn Laws eliminated about 28% tariff on imported grains.

PEEL AND THE CORN LAWS

- In 1836, the first Anti-Corn Law Association was founded in London. By 1838, strategist Richard Cobden and orator John Bright had established a nationwide league based in Manchester. Early attempts at the league imitated the tactics of abolitionists, such as the use of pamphlets and the organisation of emotionally charged meetings and speeches. Throughout the 1830s, the league targeted big cities to gain free trade supporters.

- Influenced by the works of economists Adam Smith, David Ricardo and David Hume, Peel supported free trade during his second term as PM. The role of Cobden was also significant in the support of Peel. Further triggered by the Great Irish Famine from 1845 to 1849, PM Peel pushed for repealing the Corn Laws. His radical move alienated landholders, including some Conservatives.

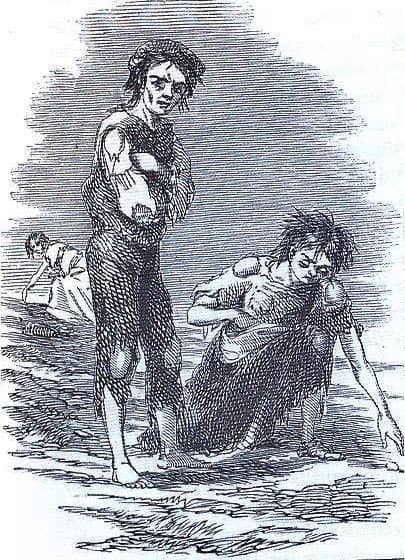

Depiction of the Potato Famine in Ireland, published in The Illustrated London News, in 1847 - As a result, the Conservative Party failed to support the Importation Bill but still gained a majority from the Whig and Radical support. It passed the House of Commons with 327 votes to 229, while the Duke of Wellington urged the House of Lords to do the same. Though aware of the negative impact of repealing the laws, Peel decided to do so.

- According to historian Boyd Hilton, Peel knew he would be deposed as leader of the Conservative Party upon repealing the Corn Laws. The issue had divided the party between liberals and paternalists since the 1830s. A hypothesis surfaced that Peel had ignored the divide hoping to lead a Peelite-Whig-Liberal alliance. Despite the significant effect of the Importation Act of Peel’s ministry, it had little impact on Ireland regarding subsidising food, which was not a typical government move at the time. For some historians, repealing the Corn Laws was more political than humanitarian.

- On 27 January 1846, Peel laid plans for gradually reducing tariffs until 1849. Among the forceful opponents of the repeal were Benjamin Disraeli and Lord George Bentinck, who believed that the act would weaken the influence of landowners and empower commercial interests. Ultimately, the Corn Laws were repealed, and Peel fell from power. Those loyal Conservatives, including the Earl of Aberdeen and William Gladstone, became known as Peelites. By 1859, the Peelites formed a coalition with the Whigs and Radicals and became known as the Liberal Party.

LATER CAREER AND DEATH

- The motion governing the House of Commons Library’s scope and collection policy for the rest of the century was passed by Peel, who served on the committee in charge.

- On 29 June 1850, Peel was knocked off his horse while riding Constitution Hill in London. The horse knocked him over, and three days later, on 2 July, he passed away at 62 from a ruptured subclavian artery brought on by a broken collarbone.