The Directory Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about The Directory to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- Creation of the French Directory

- Inflation

- Days of Terror

- Royalists’ Coup

- Military Victories

- End and Impact

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Directory (France)!

The Directory, also known as the Directorate, acted as the executive body, consisting of five people, of the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 to 10 November 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew it in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced it with the Consulate. The last four years of the French Revolution were known as the Directoire. The word is commonly used in mainstream historiography to describe the time frame from the dissolution of the National Convention on 26 October 1795 until Napoleon’s coup d’état.

BACKGROUND

- The Reign of Terror, led by the Jacobins, ended on 28 July 1794 when Maximilien Robespierre and 21 of his associates were executed by guillotine in Paris. During the subsequent 15-month period, known as the Thermidorian Reaction, Jacobin radicalism was abandoned and more conservative policies that benefited the bourgeoisie were implemented.

- The Thermidorians dismantled the extreme Jacobin laws in an attempt to revive the revolutionary ideas of 1789. The Jacobins themselves were persecuted during the First White Terror and the Jacobin Club was permanently closed in November 1794.

- They stopped the persecution of the nobles and the Catholic Church

- They promised justice but failed to address food shortages during the winter of 1794–1795

- The issuance of new batches of assignats led to increased inflation

- The return of émigrés led to a resurgence of royalism and criticism of the Republic

- Royalists launched a well-funded media campaign criticising the Republic and romanticising the former monarchy

- Despite the Thermidorians’ claim that their defeat of Robespierre saved France, the Republic was clearly in a bad state. In 1795, social unrest manifested itself in the form of popular uprisings, first from the Jacobin left (Prairial Uprising), then from the royalist right (revolt of 13 Vendémiaire), since France’s economic position was hardly better than it had been before the Revolution. These signs indicated a serious illness that threatened the Republic’s survival. Thermidorians and others in France believed that the solution was to adopt a new constitution.

- Since the monarch was deposed in August 1792, the country had been without a constitution. The Jacobins had drafted one of their own, but the Thermidorians rejected it as utopian and unworkable. The Thermidorians formed an 11-person committee to draft a constitution more in line with their goals. The document, completed in August 1795, called for the establishment of a new government. The French Directory was such a government, ruling France for four tumultuous years from 2 November 1795.

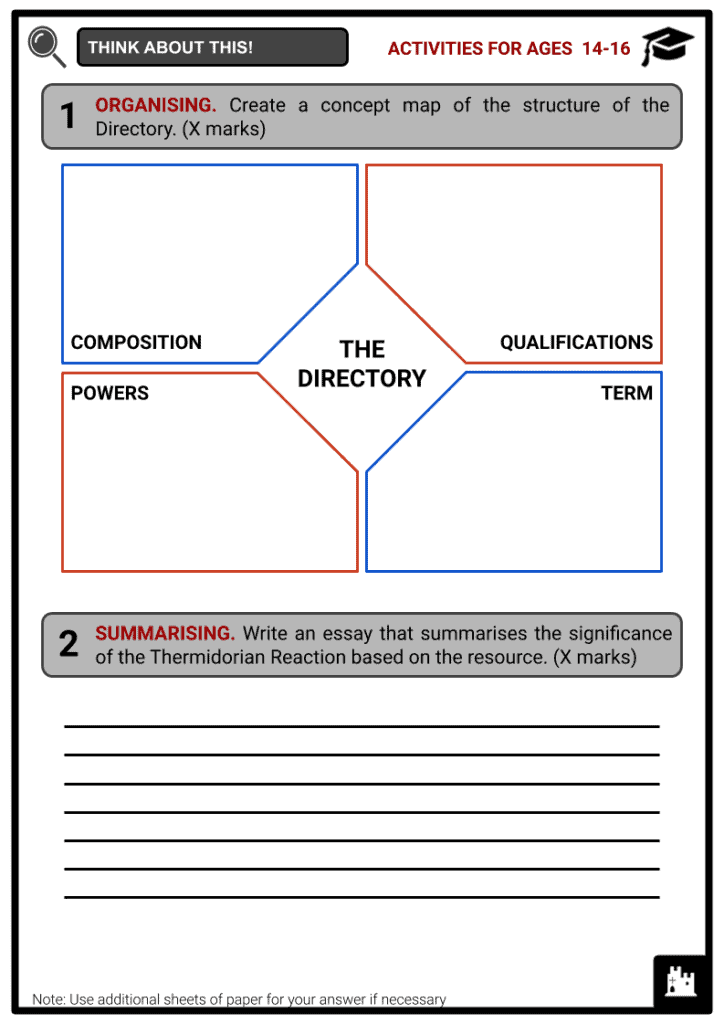

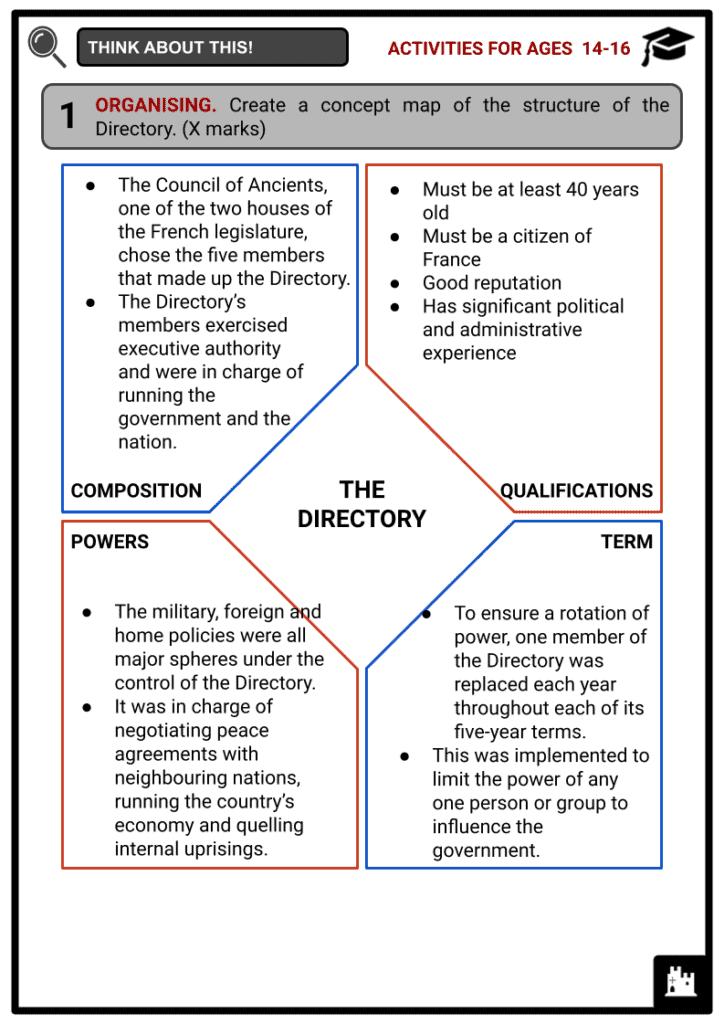

CREATION OF THE FRENCH DIRECTORY

- The Constitution of Year III (1795) was less democratic than its predecessors, limiting voting to male taxpayers over 21 years old who owned or rented land. This reduced the number of qualified voters from over 6 million to around 1 million. The new constitution aimed for stability by making it difficult to amend and by replacing the 48 Parisian districts with 12 arrondissements.

- The government was composed of the Corps Législatif, which consisted of the Council of Ancients and the Council of 500.

- The Council of Ancients, made up of 250 delegates over 40, had the power to veto or adopt laws, while the Council of 500 proposed legislation.

- The executive power was held by five Directors, each over 40 and with prior ministerial or parliamentary experience, selected by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the Council of 500.

- The Directors were replaced annually through a random draw to maintain a separation of powers.

Members of the Directory

- Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras:

- Member of a minor noble family from Provence.

- Revolutionary envoy to Toulon where he met and promoted Bonaparte to captain.

- Removed from the Committee of Public Safety by Robespierre.

- Helped organise the downfall of Robespierre.

- Expert in political intrigue and became the dominant figure in the Directory.

- Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux:

- Fierce republican and anti-Catholic.

- Proposed to execute Louis XVI after the flight to Varennes.

- Promoted the establishment of a new religion, theophilanthropy, to replace Christianity.

- Jean-François Rewbell:

- Expertise in foreign relations.

- Firm moderate republican who voted for the death of the King.

- Opposed Robespierre and the extreme Jacobins.

- Opponent of the Catholic Church and proponent of individual liberties.

- Étienne-François Le Tourneur:

- Former captain of engineers and specialist in military and naval affairs.

- Close ally of Carnot in the Directory.

- Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot:

- Army captain at the beginning of the Revolution.

- Vocal opponent of Robespierre and member of the commission of military affairs.

- Energetic and efficient manager who restructured the French military and helped it achieve its first successes.

- ‘The Organiser of the Victory’ and later became Napoleon’s Minister of War.

INFLATION

- The issue of inflation was one of the new Directory’s most pressing problems. By December 1795, the assignat currency’s value had decreased to 1% of its face value. In Paris, bread cost 50 livres, butter cost 100 livres and soap cost 170 livres. A British embargo and a subpar harvest season had further raised prices, requiring the government to rigorously ration all commodities, candles and fuel.

- The assignat was eventually abandoned in February 1796, as it was evident at this stage that it could not be salvaged. The printing presses that had been used to produce assignats were destroyed in a ceremony on the Place Vendôme.

- The Directory replaced the assignats with mandats territoriaux, a new type of currency. The value of the national estates that had been seized from the nobility or the church was backed by the mandats, which were paper currencies. The mandates were demonetised in February 1797, just a year after their initial issue, having failed even faster than the assignats. The mandats’ failure resulted in the reintroduction of metal money and, reluctantly, the creation of a central bank by 1800.

- In addition to rising inflation, the Directory had to contend with the same massive national debt that had triggered the Revolution. By declaring bankruptcy on two-thirds of the debt and committing to pay the remaining one-third, the Directory was able to stabilise the situation.

- The Directory attempted to increase its revenue by imposing additional taxes on luxury goods, but the treasury was primarily maintained by the successful French army. Each city that was conquered was required to transfer a substantial sum of money to Paris. Moreover, French generals looted conquered nations for their magnificent artworks, which they used to fill the Louvre, recently converted into a museum. The Italian Campaign of Napoleon in 1796–1797 brought in a considerable amount of money.

DAYS OF TERROR

- Food shortages and economic problems in France did nothing to alleviate the widespread suffering experienced by the country. As the winter of 1795–1796 proved to be just as severe as the previous year, people began to yearn for simpler times gone by. For Jacobins and poor sans-culottes, this meant the time during the Terror, when bread was affordable and the Constitution of 1793 had been a ray of hope.

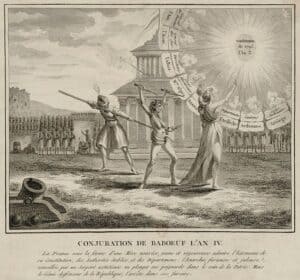

- In late 1795, like-minded revolutionaries gathered at the Pantheon Club, which had taken the place of the Jacobin Club.

- They listened to dramatic readings of the radical journal Le Tribun du Peuple, published there and written by agitator Gracchus Babeuf.

- Babeuf advocated community ownership instead of private property, a position ultimately linked to communism.

- The Directory ordered General Napoleon Bonaparte to close the Pantheon Club on 27 February 1796. Babeuf and his associates planned a coup to remove the Directory in the spring of 1796.

- The Conspiracy of Equals was discovered by the Directory, who ordered the arrests of Babeuf and his accomplices on 10 May 1796.

Conspiracy of Equals - Babeuf and one other conspirator were executed on 27 May 1797, and seven others were deported.

- The execution of Babeuf did nothing to quell societal anger, which later manifested among the political right.

- The royalists, nostalgic for earlier times, desired a new monarch and disagreed on how to reinstate it. Some wanted a constitutional monarchy, while others wanted absolutism. They set aside their differences and planned to seize control through legitimate means by targeting the Directory’s initial elections in the spring of 1797.

- The royalists launched propaganda from the Clichy Club, highlighting the poor living conditions and the Directory’s corruption. The Directory removed the vote from aristocrats still on the émigré list, but the 1797 elections showed their unpopularity. Only 11 of the 234 lawmakers were re-elected, while the royalists won 182 seats, and General Jean-Charles Pichegru was elected to lead the Council of 500.

ROYALISTS’ COUP

- The emergence of royalists indicated that the republic was in danger, with Britain and Austria moving to secure peace talks with a fragmented France. However, the generals, especially Hoche and Bonaparte, rejected this as they were aware of Pichegru’s plan to overthrow the government with a military coup, which was revealed in secret letters from Bonaparte to the Directors. In 1797, Directors Barras, Rewbell and La Révellière planned a coup to seize power in France. Soldiers under General Hoche landed in Paris and were joined by soldiers under General Augereau.

- The coup took place on 4 September 1797 and resulted in the capture of the city’s fortifications and encirclement of the legislative buildings.

- 53 deputies were detained, including Pichegru, and two Directors who did not participate in the coup were dismissed.

- The most recent elections were cancelled, leaving 177 seats empty, and anti-royalist laws were put into effect. Émigrés were given two weeks to depart or risk execution, and 160 aristocrats were put to death.

- The clergy was required to take an oath against royalism or risk being expelled, and churches were seized and rededicated as temples for the new deistic religion theophilanthropy.

- These anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic laws encouraged a Jacobin revival, and a significant number of Jacobin voters turned out for the 1798 elections, which were held between 9 and 18 April. Following Fructidor, the royalists were prohibited from running in elections, and the moderates were still in disarray following their defeat in the 1797 elections, allowing the Jacobins to seize control of the Corps Législatif.

MILITARY VICTORIES

- During the age of the Directory, French military triumphs resulted in the transformation of the Dutch Republic into the Batavian Republic, the end of the Vendée War, and the unsuccessful French Expedition to Ireland under the command of Lazare Hoche, who passed away in 1797, ending his plans for a second invasion of the British Isles. These events unintentionally laid the groundwork for the Napoleonic Wars.

- Elsewhere, French troops appeared unstoppable, particularly in Italy, where Bonaparte astonished Europe with his audacity and military prowess. After the Fructidor Coup crushed the Coalition’s hopes of negotiating with sympathetic royalists, Austria signed the Campo Formio Treaty in October 1797, ending the War of the First Coalition and leaving only Great Britain at war with France.

- Overconfident French diplomats forced the German states to cede the left bank of the Rhine during the Congress of Rastatt in 1798. The French, who had already occupied Belgium, had ambitious plans for expansion.

- European nations were alarmed by French aggression, especially after France established the Helvetic Republic and invaded the Papal States.

- The Helvetic Republic was established in January 1798 after a coup in Switzerland, granting France access to the Alpine passes.

- Napoleon invaded the Papal States in February 1798 after a French general was killed during a riot in Rome.

- He founded a sister republic in Rome and imprisoned Pope Pius VI, who died in France a year later.

- The breaking point came with Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign, which began in July 1798. Bonaparte and Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, the French minister of foreign affairs, initiated the plan to take Egypt from the Ottomans.

- European nations found this apparent act of aggression unbearable, and in 1798 they began to assemble another coalition to fight France. After only a year of peace, this led to the conflict of the Second Coalition, which plunged Europe back into total war.

END AND IMPACT

- In October 1799, General Bonaparte, who was then a popular figure, returned from Egypt. By this time, the neo-Jacobin hegemony of the legislature had been established by the elections of 1799. Napoleon’s own brother Lucien, a fervent Jacobin, had been chosen as the President of the Council of 500, despite being just 24 years old.

- Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès was appointed a Director the same year. Sieyès, who disagreed with the Constitution of Year III, saw this as an opportunity to launch his own coup and establish a new administration. He won the support of important people like Talleyrand, but he knew he would need a popular general to lead the coup. General Joubert, Sieyès’ initial choice, was killed in action, so he opted for the wildly popular Napoleon Bonaparte.

Emmanuel Sieyès - Napoleon and his army were successful in their ensuing Coup of 18 Brumaire on 9 November. With Lucien Bonaparte’s assistance, they forced the Directory to dissolve.

- A French Consulate consisting of Sieyès, Roger Ducos and Napoleon was established in its place.

- Napoleon outmanoeuvred his fellow consuls and became the driving force behind the new Constitution of Year VIII, but he had no intention of being the least senior member of the triumvirate.

- Soon, Napoleon became First Consul and was well on his way to becoming the French emperor. After the Directory, the French Revolution was finally over.

- The Directory brought stability, centralised power, implemented economic reforms and led to military conquests. However, it also led to corruption and abuse of power and paved the way for the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who ultimately ended the Directory with a coup d’état. Overall, it was a period of significant change and development in France.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Place_Vend%C3%B4me#/media/File:Place_Vendome,_Paris_20_April_2011.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_of_the_Equals#/media/File:Conjuration_des_%C3%A9gaux.JPEG

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Joseph_Siey%C3%A8s#/media/File:Emmanuel_Joseph_Siey%C3%A8s,_by_Jacques_Louis_David.jpg