The Revolutions of 1820 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Revolutions of 1820 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Prologue

- The Revolutions of 1820: Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece

- Aftermath of the Revolutions

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Revolutions of 1820!

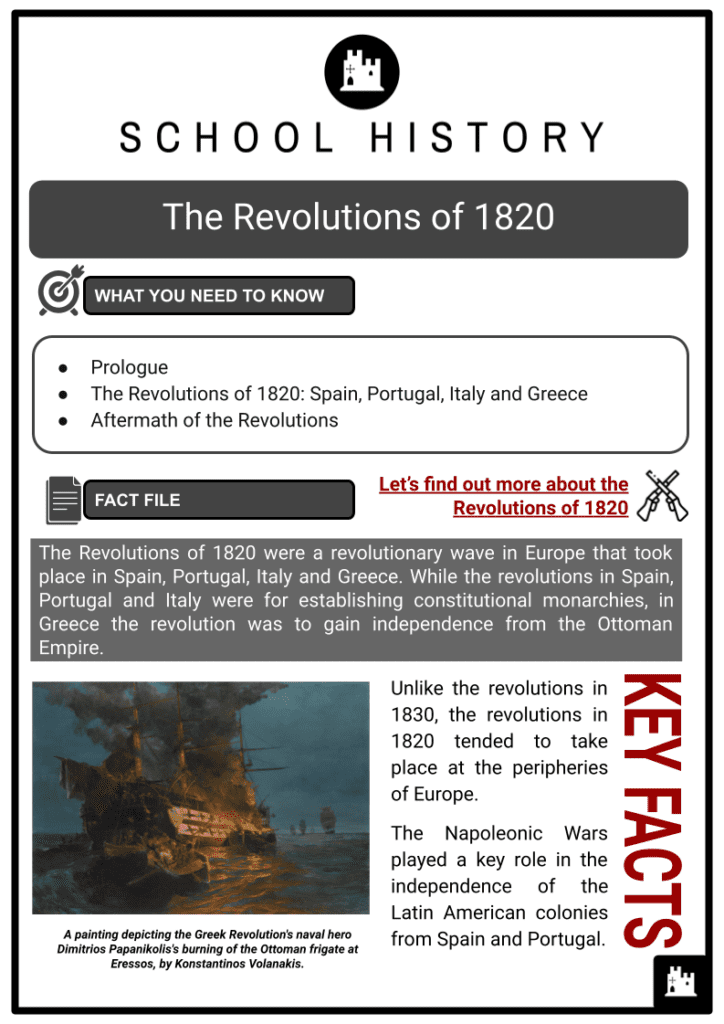

The Revolutions of 1820 were a revolutionary wave in Europe that took place in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece. While the revolutions in Spain, Portugal and Italy were for establishing constitutional monarchies, in Greece the revolution was to gain independence from the Ottoman Empire. Unlike the revolutions in 1830, the revolutions in 1820 tended to take place at the peripheries of Europe. The Napoleonic Wars played a key role in the independence of the Latin American colonies from Spain and Portugal.

Lord Byron, the famous British poet, supported the liberation movement in Italy and even actively fought in the Greek War of Independence. He spent his fortune supporting the Greeks and ultimately gave his life to Greece, a country that wasn’t even his homeland. Secret societies played a great role in the fight against both conservatism and Ottoman rule.

Prologue

- The Revolutions of 1820 were the first challenge to the conservative order of Europe established after the fall of Napoleon I in 1815. Whereas most failed, they showed the growing power of the liberal-nationalist movement, which would eventually overthrow the conservative order.

- The years following 1815 were relatively quiet. After years of revolution and war, most Europeans were relieved to see peace and order restored. However, a disgruntled liberal-nationalist minority formed secret societies dedicated to ousting the existing system. The Carbonari was the most important, playing a key role in the 1820 revolutions.

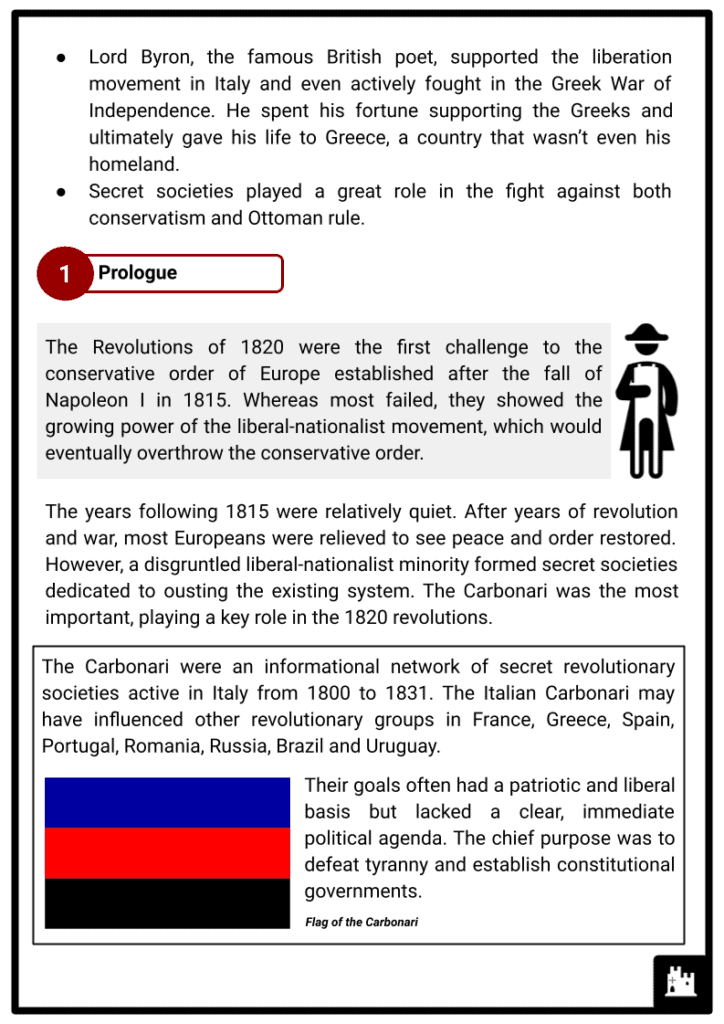

- The Carbonari were an informational network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from 1800 to 1831. The Italian Carbonari may have influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Brazil and Uruguay. Their goals often had a patriotic and liberal basis but lacked a clear, immediate political agenda. The chief purpose was to defeat tyranny and establish constitutional governments.

- In the north of Italy, other groups such as the Adelfia and Filadelfia were associated organisations. Prominent members of the Carbonari included Giuseppe Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Marquis de Lafayette, Lord Byron, Gabriele Rossetti and Louise Auguste Blanqui.

The Revolutions of 1820: Spain and Portugal

- In 1807 the Portuguese royal family and court had to flee from Portugal due to Napoleon’s approaching armies. Portugal, being a long-term ally of Britain, ignored the Continental System imposed by Napoleon, which forbade countries to continue trade with England.

- The Portuguese royal family was escorted by the British navy to Brazil to escape from Napoleon’s troops. In 1808, after arriving in Brazil, the Portuguese decided to open the ports of Brazil to ‘all friendly nations’. In 1810, the Anglo-Brazilian Treaty imposed higher tariffs on Brazil than it did on the British.

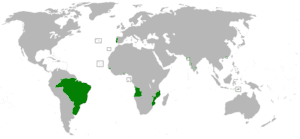

A modern map of the 1800 United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves with its colonies. - The war with France concluded in 1815, but the Portuguese royal family refused to come back to Portugal.

- In December 1815, Brazil was raised to the rank of a kingdom by John VI, who was then crowned King of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Since the departure of the Portuguese royal family, Portugal was ruled by a British pro-consul by the name of Beresford. Portugal as an independent nation collapsed: it was destroyed by the previous three French invasions, its economy was dominated by British soft imperialism and, politically, it was subordinate to Brazil and Britain. The Portuguese people arrived at a dead-end situation: they were poor and enslaved.

- In 1817, the Masonic leader General Gomes Freire de Andrade tried a coup against Beresford. It failed and he was executed. This execution put an end to the daily diminishing possibility of a peaceful penetration of Portugal by English constitutional methods. After the execution, unrest increased and when Beresford himself went to Brazil to get instructions and power from John VI, the revolution began in Porto and spread all over the country.

- In October, a government was imposed by force in Lisbon, and the Spanish constitution of 1812 was temporarily applied in order to elect a constituent assembly. The first Portuguese constitution was proclaimed in 1822.

A portrait of Pedro I, also known as ‘The Liberator’. - The Portuguese monarchy’s political constitution established a constitutional monarchy in Portugal. It declared that sovereignty rested in the nation and established the liberal separation of powers in three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. It also provided a catalogue of individual rights to be protected.

- In 1821, John VI was forced to return to Portugal to swear the constitution. But his son Pedro, who remained in Brazil as his representative, declared Brazil’s independence in 1822.

- In 1825, John VI recognised the independence of Brazil, something he had already been preparing at least since 1815 in agreement with Britain and the United States. Portugal, a founding member of the Atlantic World, was trapped in the conflict triggered by the democratic revolutions and new European imperialism. Through emerging global powers and new political actors, liberalism arrived in continental Portugal.

- In Spain, a revolution occurred in January 1820. From 1820 to 1823, Spain was ruled by a liberal government as a result of the January 1820 uprising led by Rafael del Riego against Ferdinand VII’s absolute monarchy.

- On 1 January 1820, Rafael del Riego and other liberal officers started a mutiny with the objective of the re-establishment of the 1812 Constitution, a set of laws that permitted the formation of delegates from the Spanish Colonies in America as well as the Philippines. On 7 March 1820, the royal palace in Madrid was surrounded by General Francisco Ballesteros. By 10 March, Ferdinand VII had agreed to restore the constitution.

- The period between 1820 and 1823 in Spain was known as the Trienio Liberal (Liberal Triennium) and was led by the liberal government. It only lasted for three years because in December 1822, in the Congress of Vienna, Ferdinand VII asked for the assistance of the other absolute monarchs in Europe to restore his leadership in Spain. From April to November 1823, the French army was mobilised, as per the instruction of their Bourbon King Louis XVIII, to help the Spanish Royalists. Led by the Duke of Angoulême, the French army was called the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, and was successful in the restoration of absolute monarchy in Spain.

The Revolutions of 1820: Italy

- In 1820, the Spanish people successfully revolted over disputes about their constitution, which influenced the development of a similar movement in Italy.

- Inspired by the Spaniards, a regiment in the army of the Two Kingdoms of Sicily, commanded by Guglielmo Pepe (a Carbonaro), the army mutinied and conquered the peninsular part of the Two Sicilies.

- Before these actions, Pepe was interested in the Carbonari: he organised them into a national militia, intending to use them for political purposes. He had hoped that Ferdinand I, the king of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, would grant a constitution similar to that of the Spaniards. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was a nest of Carbonari that infiltrated almost all social classes. Their name came from their trade of charcoal-burning. They were divided into Masonic-type lodges and had secret titles, codes, rituals and more.

- Their flag was red, white and black, a banner that remained the symbol of liberal revolution in Italy until it was replaced by the present-day red, white and green in 1831.

- They grew in strength after the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, and became the focal point of the 1820 revolution. For a time, at least, the revolution succeeded in wringing a constitution out of the autocratic Bourbon ruler Ferdinand I.

A portrait of King Ferdinand IV of Naples, who reigned from 1816 to 1825, c.1772–1773. - The uprising of 1820 in Naples seemed successful at first. Despite the ruthless measures to eliminate the secret society, Ferdinand was faced with the fact that his own armed forces were infiltrated with Carbonari members. Therefore, Ferdinand I was forced into conceding a constitution for his kingdom. In reaction to this, a new congress was convened in Troppau in 1820.

- This move gave the king the authority to seek aid from Austria. He left Naples after swearing an oath to the constitution and quickly hastened to Austria. He returned with an army of 50,000 men to put down the rebellion. This time he was sure that no Carbonari were in his ranks. They were met by a Neapolitan force of 8,000 men, which they defeated at Rieti on the 7 March 1821. A few days later, the king returned to Naples in triumph at the head of an Austrian army. He dismissed the parliament and tore up the constitution.

- The inevitable trials of ‘traitors’ ensued, followed by the inevitable executions. It is from this date that a constant foreign presence in Naples, either the Austrian army of Swiss mercenaries, was necessary to support what had become the last bastion of absolutism in Europe. Despite this, during the 1830s, Carbonari-related activity spread to Piedmont, Lombardy, Parma, Modena, Romagna and the Papal States. It even attracted foreigners who had taken up the cause of Italian unity: Lord Byron, for one, who would go on and even fight in the Greek War of Independence.

- The Carbonari are historically regarded as the forerunners of the Risorgimento, the mid-19th-century movement to unify Italy, because of their identification with the cause of national unity.

- From the revolution of 1820 to the fall of the Kingdom of Naples in 1860, the Bourbon rulers proved singularly inept at dealing with the forces of liberalism other than through outright suppression.

The Revolutions of 1820: Greece

- Though the revolution in Italy ended in failure, the Greek War of Independence from 1821 to 1830 against the Ottoman Empire was a successful endeavour.

- Even after several decades since the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, most of Greece had come under Ottoman rule. Countless times the Greeks attempted to gain independence from the Ottoman Empire through revolutions. The Filiki Eteria (Friendly Society), a secret organisation, was founded in 1814 with the goal of liberating Greece.

- The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolts in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities, and Constantinople and its surrounding areas.

The Danubian Principalities - By late 1821, their plans for a revolution on 25 March had been discovered by Ottoman authorities. This prompted the revolutionary action to start earlier. The first of these revolts began on 6 March, in the Danubian Principalities, but the Ottomans quickly put down the rebellion.

- These events pushed the Greeks in the Peloponnese region to take action and on 17 March, the Greeks declared war on the Ottomans. This declaration marked the beginning of a spring of revolutionary actions against the Ottoman Empire by other controlled states. On 25 March, the revolution was officially declared and by the end of the month the Peloponnese was in open revolt against the Turks.

- The Greeks led by Theodoros Kolokotronis had captured Tripolitsa by October 1821. The Peloponnesian revolt was quickly followed by those in Crete, Macedonia and Central Greece. They were all suppressed. However, the Greek navy began to win certain battles against the Ottoman navy in the Aegean Sea, thus preventing the Ottomans from sending reinforcements by sea.

- Regardless of their common enemy, tensions began to rise among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. The Ottoman Sultan profited from this, initiating negotiations with Mehmet Ali of Egypt for an alliance. Mehmet agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain.

- Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese region in February 1825 and had immediate success. By the end of 1825, most of the Peloponnese was under Egyptian control with the city of Missolonghi being captured in April 1826 after a year of siege by the Turks.

- Ibrahim was later defeated in Mani, yet he succeeded in suppressing the majority of the revolts in the Peloponnese, leading to the recapture of Athens. The Russian Empire, the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of France, and several other European powers later aided the Greeks. The Ottomans were aided by their vassals, the Eyalets of Egypt, Algeria, Tripolitania, and the Beylik of Tunis.

- The 1828–1829 Russo-Turkish War was triggered by the Greek War of Independence. The war broke out after the Sultan closed the Dardanelles to Russian ships and revoked the Akkerman Convention in retaliation for Russia’s participation in the Battle of Navarino.

- The Treaty of Adrianople concluded the Russo-Turkish War of 1829. The final step in the acquisition of Greek independence was its recognition as a sovereign state under the London Conference, and the Treaty of Constantinople defined the final borders of the new state. It established Prince Otto of Bavaria as the first king of Greece. The Greek Revolution is celebrated by the Greek state as a national day on 25 March.

Aftermath

- The Revolutions of 1820 and 1830 showed that the ideals of the Enlightenment were here to stay. The concepts of independence, nationalism and safeguarding against corrupt rule were all easily assimilated by the people as they felt natural.

- The revolutions left many issues unresolved like the issues of the working classes and the inequality of wealth. It would take some countries even more revolutions, some countries fewer, to achieve a form of equality and equilibrium. Sadly, it would even take a couple of wars, the likes of which the world had never seen before, to slowly walk towards these goals.

Image Sources

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Κωνσταντίνος_Βολανάκης_-_Το_κάψιμο_της_τουρκικής_φρεγάτας.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portuguese_empire_1800.png

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Dom_Pedro,_Duke_of_Bragança_-_Google_Art_Project_edited.jpeg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mengs_-_Ferdinand_IV_of_Naples,_Royal_Palace_of_Madrid.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rom1856-1859.png