Thermidorian Regime Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Thermidorian Regime to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Thermidorians

- Fall of the Jacobins

- White Terror

- Thermidorian Policy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Thermidorian Regime!

The Thermidorians rose to power by plotting to assassinate and remove Maximilien Robespierre. The Thermidorian government began to end the Reign of Terror after the execution of Robespierre by firing the Jacobins from positions of authority and ruthlessly repressing their beliefs during the First White Terror.

THERMIDORIANS

- The term Thermidorians, which applied to those who plotted to overthrow the Robespierrist government, comes from the French Republican calendar month of Thermidor, which falls in the middle of the summer, the time of the coup. The Thermidorians disliked Robespierre, but that was all they had in common.

- Many were conservative Republicans who stood for the centrist ‘Plain’ group of Convention deputies and wanted to return to the Revolution’s earlier years, before the Terror, in 1792. Others wanted to go even further and called for another constitutional monarchy attempt similar to the one in 1791. There are some factors that contributed to the unpopularity of the Thermidorian Convention.

- The lack of consensus and the absence of dominating personalities contributed to the ineffectiveness and unpopularity of the Thermidorian Convention.

- At best, their critics saw them as a forgettable interlude between Robespierre and Napoleon. At worst, they were the Revolution’s gravediggers – former revolutionaries lured and corrupted by the glories of power. According to historian Bronisaw Baczko, Thermidorians were only being realistic. The Revolution had lost much of its vigour, bringing it closer to exhaustion each month. The fact that the Revolution could no longer fulfil the promises made in 1789 was becoming increasingly apparent.

- Therefore, Baczko contends that the Thermidorians knew these constraints and tried to work around them rather than deliberately burying the Revolution. Many French citizens preferred stability over revolutionary advancement following the violence of the Reign of Terror, which the Thermidorians sought to provide. In any case, the Thermidorian Reaction represented a form of counter-revolution, turning away from the bold advancement of the Jacobins and returning to steadfast conservatism.

FALL OF THE JACOBINS

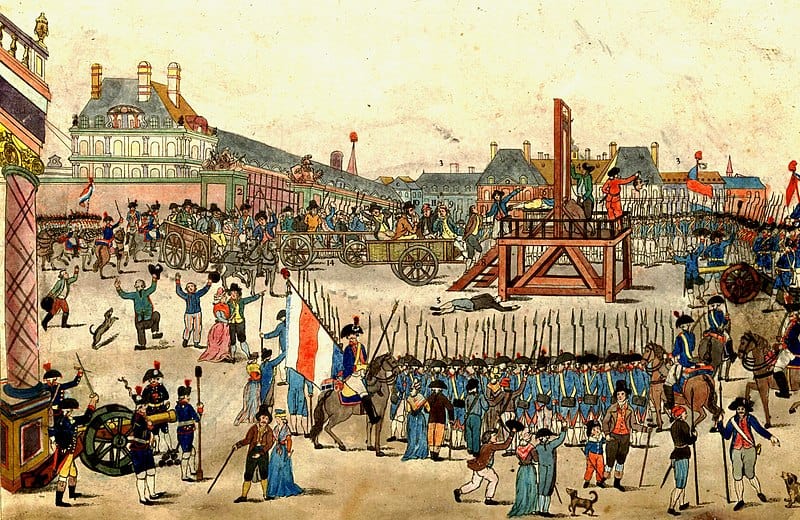

- The execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794 ended France’s Reign of Terror after months of bloodshed. By then, the Terror had killed anywhere from 20 to 40,000 people, leaving many of France tired of the constant carnage.

- Many Convention deputies had given Robespierre a reason to despise them, making them worry that they would be executed next, although he avoided dropping names. They decided to attack first and successfully overthrew Robespierre, who was put to death when a bullet destroyed his jaw. The conspirators, later known as Thermidorians, resolved to secure their victory by securing the final destruction of the Mountain (the Jacobins’ political group), with Robespierre no longer in the picture.

- They started by destroying the Terrorists’ weapons and punishing those who had used them. The Committee of Public Safety was reduced to one of many committees under the control of the National Convention on the day Robespierre passed away after the National Convention rejected a proposal that would have confirmed its authority. The Committee of Public Safety would no longer be in charge of France but would continue to oversee the war effort.

- The execution of 70 of the Paris Commune’s officials who had stayed faithful to Robespierre without trial on 29 July similarly ended the uprising. The most emotional members of the Revolutionary Tribunal’s staff were removed, but the organisation was briefly maintained. Most notably, Antoine Fouquier-Tinville, the notorious top prosecutor, was detained and executed.

- The Thermidorians deployed representatives-on-mission across the provinces to assure the complete de-Jacobinisation of the nation, while other Jacobins were abruptly ousted from authority. Thousands of convicts detained without trial were freed on 1 August after the Thermidorians repealed the laws that supported the Terror, specifically the Law of 22 Prairial and the Law of Suspects.

- 71 Convention representatives who were detained in June 1793 for allegedly supporting the Girondins were freed and rehired in the government.

- The infamous phrase was changed to a new one once the Reign of Terror was eventually proclaimed to be finished.

‘Terror is the order of the day.’ --> ‘Justice is the order of the day.’

- An example is that, in stark contrast to the 342 people executed there the month before, just six people were guillotined in Paris throughout August. Nearly 800 petitions lauded the National Convention for ousting the ‘scoundrel’ Robespierre and glorifying the Thermidorians as France’s new founding fathers were presented to them.

WHITE TERROR

- Not everyone was pleased with the Thermidorians’ assurance of justice. Others had not forgotten the friends and loved ones they had lost to the guillotine, while many recently freed inmates still harboured resentment towards the men who had placed them there. Many people in France advocated that retribution rather than justice prevail.

- Some anti-Jacobin organisations with this vengeful mindset started to appear in Paris and other parts of France. One such gang, the muscadins, stalked the streets of Paris while wielding wooden clubs to administer vigilante justice. Young men from the bourgeois class who attacked well-known Jacobins in back alleyways and encouraged street clashes with sans-culottes, the lower-class Jacobin sympathisers, were known as muscadins.

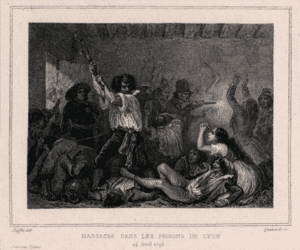

Portrait depicting the massacre of Jacobin prisoners in Lyon in 1795 - The muscadins purposefully dressed like parodies of fops, sporting wide-brimmed hats, oversized cravats, and silk stockings to ridicule Jacobin ideals. In November 1794, the muscadins invaded the Jacobin Club itself after being incited by Thermidorian-aligned journals, disrupted Jacobin meetings and beat up anyone they found there. The convention decided to permanently close the Jacobin Club instead of prosecuting the attackers, presumably to deter further lawlessness. The Jacobin Club was formally banned shortly after that.

- The Thermidorians continued to persecute former Jacobin leaders in the meantime. In the same month that the Jacobin Club was shut down, the trial of Jean-Baptiste Carrier, the man responsible for the horrific drownings at Nantes, captured the attention of Paris. Thermidorian media emphasised the brutality of Carrier’s acts and painted him as a spokesman for all Jacobins. During a harsh winter that resulted in famine, inflation, discontent and the failed uprising of 12 Germinal, Carrier was put to death in December.

- The Thermidorians intensified their attacks on the Jacobins in response to this rebellion. Thermidorian representatives-on-mission was given complete authority to disarm and detain individuals by the Law of 10 April, which resulted in the arrest of up to 90,000 alleged Jacobin sympathisers throughout the summer of 1795. Collot d’Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, two former members of the Committee of Public Safety, were accused, tried and deported to French Guiana despite their cooperation in overthrowing Robespierre. The message was loud and clear: former terrorists would be held accountable for their actions.

- The street violence only worsened during this second round of Jacobin repression in the spring and summer of 1795. Militias started to emerge in the provinces to pursue and kill Jacobins. In Lyon, the so-called Company of Jesus carried out this mission. In Nîmes, the Company of the Sun sought Jacobins. Typically, these organisations eschewed the orderly guillotine in favour of more intimate methods of eliminating their adversaries, such as lynch mobs, murderous gangs, kidnappings and ambushes.

Brief timeline of the First White Terror

- August – October 1794. Right-wing publications in Paris are now free to demand vengeance on the Jacobins, provide directives for action and identify notable terrorist targets.

- 2 February 1795. Massacre of Jacobin prisoners at Lyon.

- 30 March 1795. In Lyon, the threat of a massacre of prisoners and other Jacobins is now so great that Boisset orders detainees to be taken away to Roanne and Mâcon.

- April 1795. Several known Jacobins are arrested and killed during this period.

- May 1795. Military Commission to judge Prairial insurgents established.

- June 1795. Several Jacobins are murdered and members of the former Revolutionary Tribunal at Orange are killed and thrown into the Rhône.

THERMIDORIAN POLICY

- The Thermidorians overturned the Law of the General Maximum, which had capped the price of bread and other necessities to reverse the Jacobin economic policy. The Thermidorians generally supported capitalism and thought that a return to free market principles would help to revive France’s economy, which had been heavily affected by inflation.

- This idea was unfortunately put into effect by the Thermidorians during one of France’s harshest winters in 1794–1795. Without the regulation that the General Maximum promised, the cost of petrol and bread soared, while the price of meat increased by 300%. Paris experienced a rise in fatalities as people starved and froze to death or killed themselves to escape such dreadful fates. In response, the Thermidorians produced more assignats, the paper currency of the Revolution, but this just worsened the inflation issue.

Portrait showing a sans-culotte musing over a list of high food prices - Many Thermidorians would come to dislike them due to this disastrous economic strategy, and some would long for the Terror’s darkest days when bread was at least reasonably priced. Religiously, Thermidorian policies performed better. The Thermidorians established freedom of worship in February 1795 to curtail the dechristianisation initiatives that had blossomed under the Reign of Terror.

- The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which had established the Constitutional Church in 1790, was effectively abolished when they declared that the government would no longer pay for the maintenance of religious institutions. This was the first time in French history that the state and the church had been divided.

- The religiously conservative War in the Vendée rebels, who had revolted partly because of the Revolution's suppression of Catholicism, was granted this freedom of worship by the Thermidorians. A month after their proclamation, the Thermidorian Convention similarly granted amnesty to any rebel who laid down his arms. The insurrection persisted after this and was put down by General Lazare Hoche, who the Thermidorians sent in, in 1796.

- The Thermidorians also pardoned many aristocratic immigrants who fled France after the Ancien Régime's demise. Naturally, this resulted in a rise in royalist feeling as people were no longer frightened to express their support for the king.

- The idea of security under a stable monarch had become far more alluring than it may have been six months earlier due to the turmoil of the Terror and the accompanying months of deprivation under the Thermidorians. Louis-Charles, the 10-year-old son of the assassinated King Louis XVI of France, was the ideal candidate for the throne. Revolutionaries had re-educated the youngster and could make for a dedicated citizen king who might respect the constitution like his deceased father had not. Royalists were already proclaiming him as Louis XVII of France.