Trail of Tears Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Trail of Tears to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Historical Background

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

- Removal of the Cherokee Nation

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Trail of Tears!

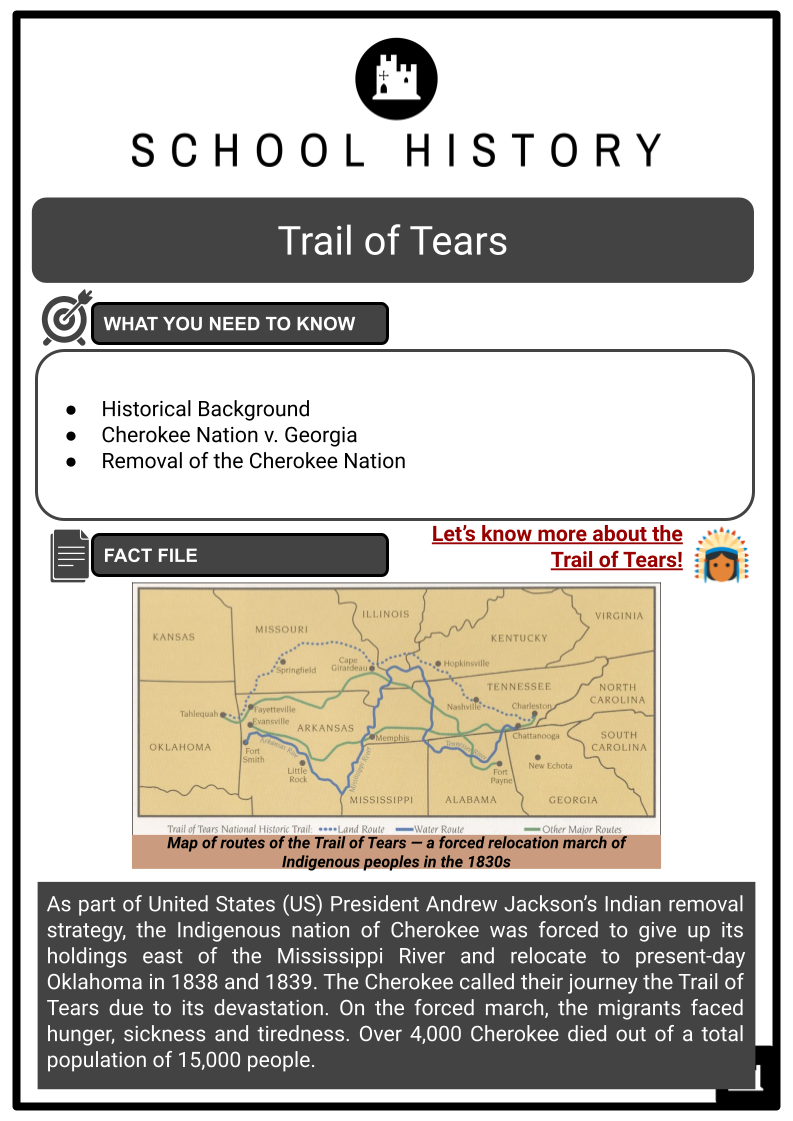

As part of United States (US) President Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal strategy, the Indigenous nation of Cherokee was forced to give up its holdings east of the Mississippi River and relocate to present-day Oklahoma in 1838 and 1839. The Cherokee called their journey the Trail of Tears due to its devastation. On the forced march, the migrants faced hunger, sickness and tiredness. Over 4,000 Cherokee died out of a total population of 15,000 people.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

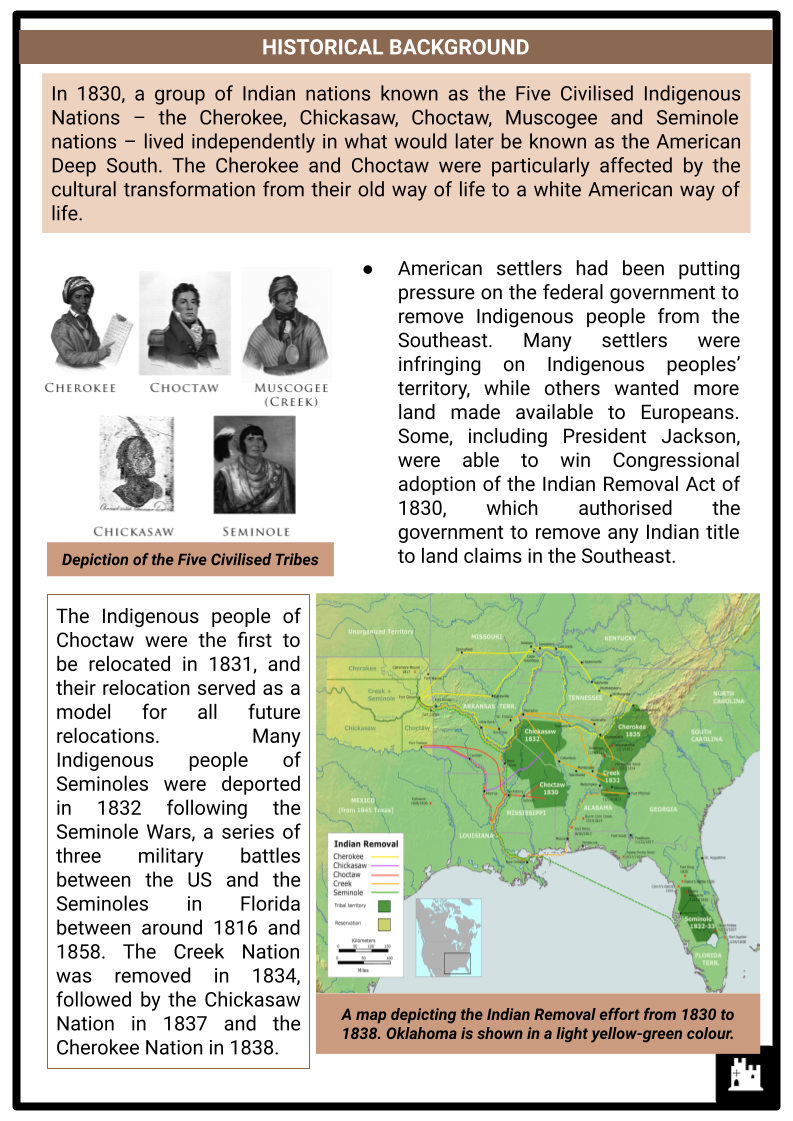

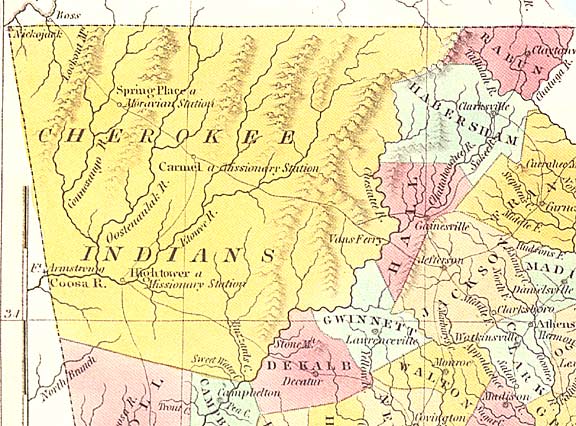

- In 1830, a group of Indigenous nations known as the Five Civilised Indigenous Nations – the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole nations – lived independently in what would later be known as the American Deep South. The Cherokee and Choctaw were particularly affected by the cultural transformation from their old way of life to a white American way of life.

- American settlers had been putting pressure on the federal government to remove Indigenous people from the Southeast. Many settlers were infringing on Indigenous peoples’ territory, while others wanted more land made available to Europeans. Some, including President Jackson, were able to win Congressional adoption of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorised the government to remove any Indian title to land claims in the Southeast.

- The Indigenous people of Choctaw were the first to be relocated in 1831, and their relocation served as a model for all future relocations. Many Indigenous people of Seminoles were deported in 1832 following the Seminole Wars, a series of three military battles between the US and the Seminoles in Florida between around 1816 and 1858. The Creek Nation was removed in 1834, followed by the Chickasaw Nation in 1837 and the Cherokee Nation in 1838.

- According to an article published on the website of the Public Broadcasting Service, 46,000 Indigenous people from the southeastern states were relocated, freeing up 25 million acres for white settlement by 1837.

- When the Five Civilised Indigenous Tribes arrived in Indian Territory, they followed their physical appropriation with an erasure of their predecessors’ history, perpetuating the idea that they had discovered an undeveloped environment when they arrived in an attempt to appeal to white American culture and values by participating in the settler colonial process themselves.

- Other Indigenous nations, such as the Quapaws and Osages, had arrived in Indian Territory before the Five Tribes and saw them as intruders.

ROLE OF ANDREW JACKSON

- Even though Jackson was not the single or original man behind the Indian Removal policy, his contributions affected its course. Jackson’s advocacy for the removal of Indigenous people began at least a decade before his administration. When he became President, Jackson’s first legislative objective was the expulsion of the Indigenous people.

- The prioritisation of American Indian removal, as well as his violent reputation, provoked unrest among US territories. Jackson and his successor, US President Martin Van Buren, carried out the removals in response to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which gave the president the authority to swap land with Indigenous nations and improve infrastructure on existing lands.

- Jackson’s motives were violent, according to historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. According to Dunbar-Ortiz, Jackson believed in bleeding enemies to bring them to their senses in his drive to serve the goal of US expansion.

- According to historian Amy H Sturgis, Jackson’s removal tactics drew criticism from respected social figures, and many leaders of Jacksonian reform movements were especially disturbed by US policy towards Indigenous people.

- According to historian Francis Paul Prucha, these conclusions were made by Jackson’s political opponents and Jackson had good intentions. He claims that Jackson never acquired a doctrinal anti-Indigenous peoples mentality and that his overarching goal was to ensure the security and well-being of the US and its Indigenous people and white residents.

TREATY OF NEW ECHOTA

- Jackson elected to proceed with the forced removal of the Indigenous nations, and on 29 December 1835, he negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which authorised the Cherokee two years to go to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). The treaty established provisions for the Cherokee Nation to renounce its southeast region and relocate to the Indian region. Although the Cherokee National Council did not accept the treaty and it was not signed by Principal Chief John Ross, it was revised and ratified in March 1836 and constituted the legal basis for the Trail of Tears.

- In February 1836, the Cherokee National Council petitioned Congress to annul the pact, signed by hundreds of Cherokee people. Only a small percentage of Cherokee departed voluntarily.

- In 1838, the US government, aided by state militias, drove the majority of the surviving Cherokee west.

- The Cherokee were imprisoned in camps in eastern Tennessee for the time being.

- In November, the Cherokee were divided into groups of roughly 1,000 people and set out west. They had to deal with torrential rains, snow and frigid temperatures.

- When the Cherokee negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, they gave up all their land east of the Mississippi for land in modern Oklahoma and a $5 million federal settlement.

- Many Cherokee felt betrayed when their leaders approved the bargain, and over 16,000 Cherokee signed a petition to stop the treaty from being signed.

- Tens of thousands of Cherokee and other Indigenous nations had been driven from their country east of the Mississippi River. Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Creek, Choctaw, Seminole and Chickasaw were also removed.

CHEROKEE NATION V. GEORGIA

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia is a landmark decision in Indigenous peoples’ law because of its ramifications for the sovereignty and legal definition of the relationship between federally recognised Indigenous nations and the US government.

- The Georgia State Legislature approved two pieces of legislation in the late 1920s that proclaimed that the Cherokee Nation’s territory might be examined, divided up and allocated to white Georgia citizens.

- Anyone who did not comply with the legislation faced sanctions and punishment. The legislation was designed to push the Cherokee nation off their lands.

- The Cherokee Nation and Ross attempted to declare the laws unlawful based on treaties signed by the Cherokee Nation and the US government.

- The Cherokee Nation claimed that the treaties guaranteed tribal sovereignty and federal protection, and therefore, the Cherokee Nation’s lands should fall outside the purview of the state’s authority.

- The Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, rejected the claim that the Cherokee Nation constituted a foreign state, as defined in the US Constitution. Instead, Justice Marshall described the Cherokee Nation as a domestic dependent nation, and the majority decision contended that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear and decide the issue.

- In a dissenting opinion, Justice Smith Thompson expressed worry that the tribe did not have a forum like the Supreme Court to pursue objections when its rights were violated.

“And if they, as a nation, are competent to make a treaty or contract, it would seem to me to be a strange inconsistency to deny to them the right and the power to enforce such a contract.” - Justice Thompson

- The majority ruling in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia was eventually overturned the following year in Worcester v. Georgia, where the Court asserted its jurisdiction to judge matters involving states and sovereign tribal nations.

REMOVAL OF THE CHEROKEE NATION

- General Winfield Scott led the Cherokee removal in 1838, with 7,000 soldiers and members of several state militias accompanying the Cherokee and other Indians west. The Cherokee were mostly in Georgia at the time of the removal, though tribal territories extended into Alabama, Tennessee, North Carolina and other states. The Cherokee pro-treaty faction signed away Cherokee lands in Appalachia and began the removal process at New Echota, Georgia.

- Despite a petition and vote to reject the terms, treaty negotiations took place at the neighbouring Red Clay Council Ground, about 13 miles south of Cleveland. Red Clay Council Ground visitors can observe where the meeting took place and view Cherokee displays.

- Rattlesnake Springs is located five miles northeast of Cleveland and was the site of the Cherokee’s final council before their westward migration.

- Despite their displacement, the Cherokee maintained Cherokee culture, language and traditions in the new area. For many, the long journey west began at Rattlesnake Springs. The Cherokee were a well-established people before they left. Visitors can tour the home and school of Samuel Worcester, a print shop, the tribal Supreme Court Building and a relocated tavern at the partially reconstructed Cherokee capital of New Echota.

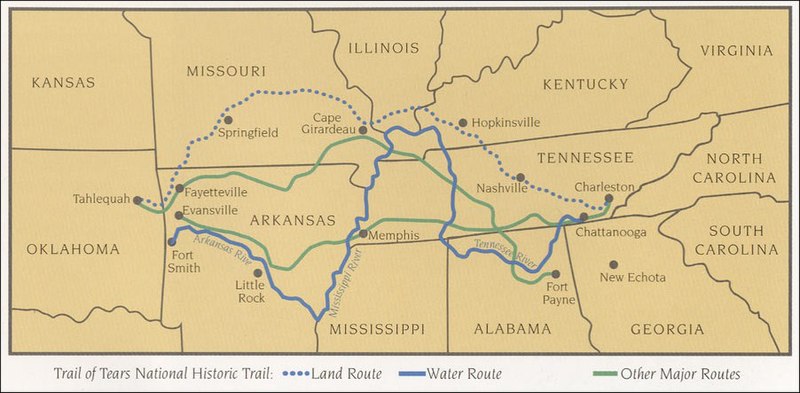

- The majority of the displaced Cherokee walked west on roads. However, some travelled by canoe.

- Most Cherokee were herded west after being rounded up into assembly centres, sent to emigration depots, and then herded again. In 1837, United States Army Lieutenant BB Cannon led a party of Cherokee who voluntarily went west.

- Armed soldiers drove the Cherokee from their houses and took their treasured things.

- They discovered that food and water were sparse in the holding centres, and disease and death were prevalent.

- The Cherokee and their armed escorts took several months to complete the march. The travellers spent a few nights at campgrounds resting between portions of the journey or waiting for weather conditions to change so they could continue west.

- Mantle Rock, now part of the Mantle Rock Nature Preserve in Smithland in Livingston County, Kentucky, contains a portion of the Cherokee roadbed and a Cherokee campsite. Mantle Rock was a massive natural sandstone arch that provided adequate cover for the Cherokee. Only some camps were in a good location.

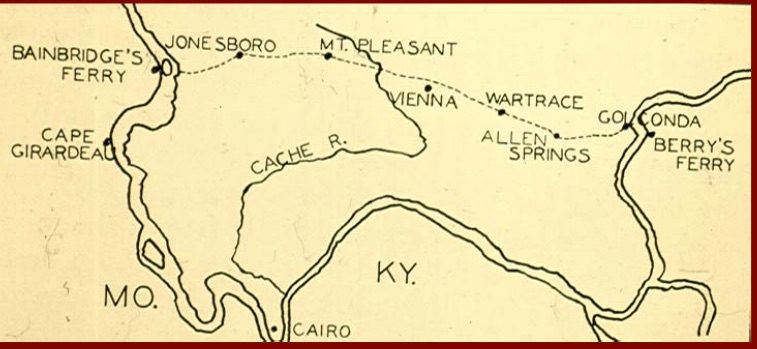

- Following Mantle Rock, 11 of 13 overland Cherokee detachments that went through the area crossed the Ohio River by ferry from Kentucky to Illinois. The Cherokee campsite at Mantle Rock were forced to wait because the ferry could only transport a few people at once. The Ohio and Mississippi rivers were frozen due to an abnormally cold winter, halting the last detachment at Mantle Rock.

- The final resting places of the Cherokee who perished at Mantle Rock are mainly unknown. There are markers at other grave sites along the trail.

- Two Cherokee elders, Whitepath and Fly Smith, travelled in the second detachment and died in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in October 1838 along the journey from Nashville to Hopkinsville. The Cherokee that made it west successfully exited the Trail of Tears at disbandment sites such as Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. When they arrived in Indian Territory, the other parties had just dispersed.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the Trail of Tears?

The Trail of Tears refers to the forced removal of Indigenous peoples nations, particularly the Cherokee, from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to designated Indian Territory in the 1830s.

- What was the main reason for the forced removal of the Indigenous peoples?

The primary reason for the forced removal was the implementation of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, which sought to clear land for white settlement.

- What were the conditions like during the forced removal?

The conditions during the Trail of Tears were harsh and deplorable. Indigenous peoples faced exposure to the elements, lack of proper provisions, and inadequate medical care, leading to widespread suffering and death.