William Howard Russell Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about William Howard Russell to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life of William Howard Russell

- The Crimean War and Russell’s War Reporting

- Russell During the Capture of Lucknow

- Later Life and Legacy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about William Howard Russell!

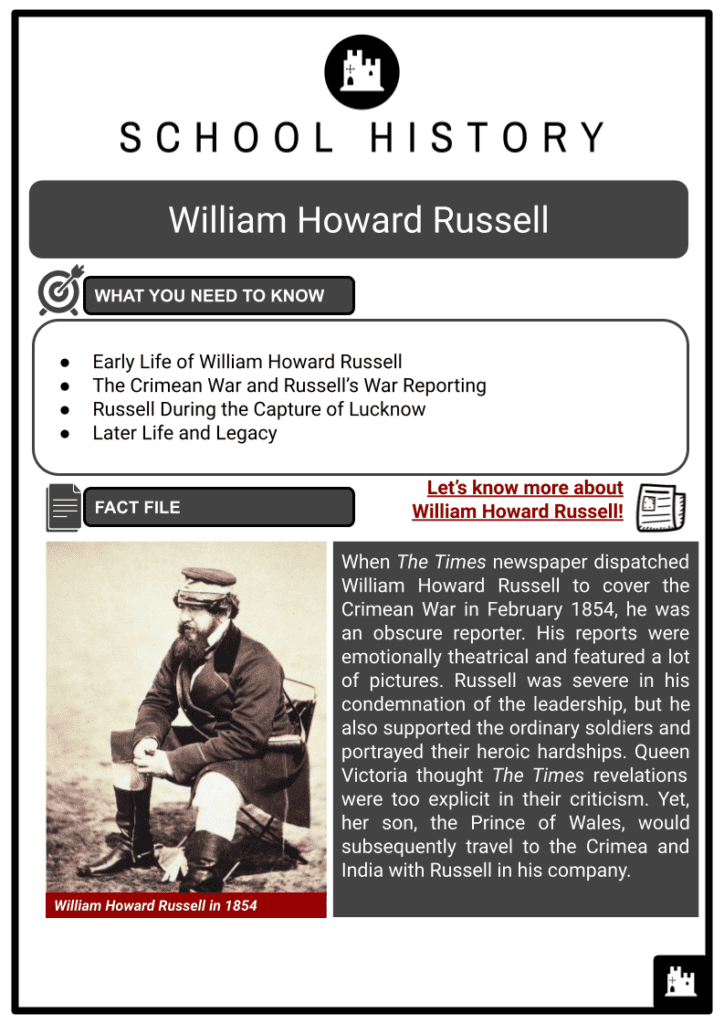

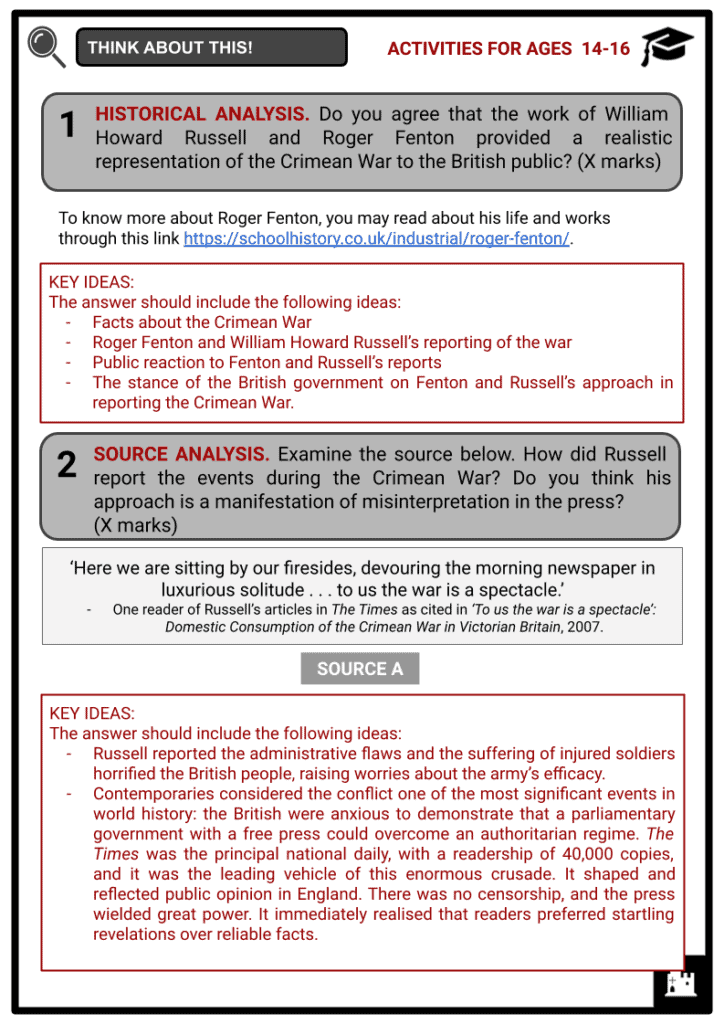

When The Times newspaper dispatched William Howard Russell to cover the Crimean War in February 1854, he was an obscure reporter. His reports were emotionally theatrical and featured a lot of pictures. Russell was severe in his condemnation of the leadership, but he also supported the ordinary soldiers and portrayed their heroic hardships. Queen Victoria thought The Times revelations were too explicit in their criticism. Yet, her son, the Prince of Wales, would subsequently travel to the Crimea and India with Russell in his company.

EARLY LIFE OF WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL

- On 28 March 1827, William Howard Russell was born in Lily Vale, Jobstown, Co Dublin. He was the son of John Russell, a successful businessman from the Co Limerick family, and Mary Russell, a Jobstown resident. Russell’s father failed in business when he was very young and moved the family to Liverpool hoping to regain his fortune through another business endeavour. Russell was placed in the care of his maternal grandparents at Lily Vale when their second son was born in 1823.

- Russell’s grandfather, Capt Jack Kelly, a Roman Catholic, was the master of the Tallaght foxhounds and was so fascinated by foxhunting that his estate suffered due to the time he spent hunting. Russell’s recollection of his boyhood at Lily Vale suggests that he relished these years as much as Capt Kelly’s oddities.

- Because of Capt Kelly’s financial difficulties, Russell relocated to the home of his paternal grandparents at 40 Upper Baggot St when he was about seven years old. His paternal grandpa, William Russell, was a Moravian church member in Dublin with strong Puritan tendencies.

- Russell attended Dr EJ Geoghegan’s school on Hume Street (1832–7) and entered TCD in 1838 but did not know what he wanted to pursue, contemplating both law and medicine. He did not apply to his studies because he did not receive a scholarship and departed in 1841 without a degree.

- In the same year, his cousin Robert Russell, who worked for The Times, approached him for assistance in writing about the general election, and he later covered the ‘monster meetings’ of 1843. He covered Daniel O’Connell’s trial in 1844 and worked as a legislative correspondent in London.

- O’Connell was known as The Liberator throughout his lifetime. In the first half of the 19th century, he was recognised as the political leader of Ireland’s Roman Catholic majority. In 1829, his mobilisation of Catholic Ireland, right down to the poorest class of tenant farmers, secured the final installment of Catholic emancipation.

THE CRIMEAN WAR AND RUSSELL’S WAR REPORTING

- Russell began studying for the law in London, enrolling as a student at the Middle Temple in 1846. He was called to the bar in 1850 but did not seriously pursue a legal career.

- Russell rejoined The Times after a stint with the Morning Chronicle (1845–8) and covered the conflict in Schleswig-Holstein in 1850. When war with Russia seemed likely in February 1854, The Times’ editor, John T Delane, sought permission from Lord Hardinge of the British army for a journalist to accompany the Guards Brigade to Malta.

- Russell was asked to go and promised to return home by Easter. He moved to Varna with the army after the declaration of war in March 1854 and then to Crimea, not coming home for nearly two years.

- Delane’s 3-month timeframe for covering the Crimean War was stretched to 22 months. Russell began reporting on the realities of the Crimean War to the British people at important events such as the Siege of Sevastopol. He earned a lasting reputation as the ‘first Special Correspondent’ for reporting on the Crimean War.

- Russell’s reports in The Times shaped the British public’s understanding of the Crimean conflict. Russell’s reports, on the other hand, as described by historians, were ‘sharp, clear, and detailed’. Russell documented the reality of warfare, as he stated the public ‘should know’ about the ‘hard truths,’ showing how Russell’s reports were far from disputable and unreliable. Russell’s reports played an integral role in the Crimean story.

- The British government did not impose press censorship in the 1850s: journalists were free to report and comment on the war without fear of undermining patriotism. While it was a diffused war, the press and the war were two wholly separate entities that worked against one another rather than in conjunction. Russell was able to criticise military errors because of this journalistic freedom.

- Russell mentions the British army’s lack of equipment during the Siege of Sebastopol in one report, saying how:

‘The wretched beggar who wanders the streets of London lends the life of a prince compared with the British soldiers.’ - Russell, William, The Times, 18 December 1854.

- Russell’s comparison and the freedom of the press explain why the newspaper maintained an undisputed place in the Crimean narrative. Russell’s reports provided the public with sufficient information and allowed them to learn about the realities of military action for the first time. Russell’s dispatches were avidly read by Britain’s literate populace, with 6,100 copies produced daily by 1855, demonstrating how newspapers were vital resources in the narrative of the Crimean War.

Queen Victoria

How did Russell get his stories during the War?

- Russell frequently interviewed troops to obtain firsthand accounts of the events of the war. He wrote about the notorious Charge of the Light Brigade, a failed military manoeuvre against Russian forces in October 1854 during the Battle of Balaclava. British army officer Lord Raglan’s mistaken order resulted in the deaths of 100 cavalrymen. Russell detailed the casualties and chastised Lord Raglan for his failure.

- Despite being widely read, Russell’s candid reporting on the horrors of war was not always well received. Russell’s lack of patriotism and assaults on Lord Raglan did not impress Queen Victoria, who stated that ‘his infamous attacks against the army have disgraced our newspapers.’ Furthermore, Prince Albert remarked that ‘the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country,’ while Secretary of War Sidney Herbert stated:

‘I trust the Army will lynch The Times correspondent.’ As cited in an article published on The Irish Times website, 2020.

- Despite these criticisms, there is little doubt that Russell’s reports in The Times contributed to bringing the harsh reality of combat to light. Russell’s candid yet critical reporting on the events in Crimea exposed the public to the reality of battle for the first time.

- This not only influenced popular views towards the war, but it also aided in the reform of medical treatment during the conflict. Russell’s dispatches and the newspaper press occupied an undisputed place in the narrative of the Crimean War: for the first time, the gap between war and the general public was bridged. As a result, Russell’s name is intimately connected with some of the most stirring incidents of the mid-19th century.

- His dispatches were extremely important because they allowed the public to read about the reality of combat for the first time. The public’s shock and outrage at his accounts compelled the government to reconsider troop treatment, resulting in Florence Nightingale’s involvement in revolutionising battlefield medicine. During the Crimean War, Nightingale rose to fame as a nurse manager and teacher, organising treatment for wounded soldiers in Constantinople.

- Russell left Crimea in December 1855, to be replaced by The Times’ correspondent in Constantinople.

RUSSELL DURING THE CAPTURE OF LUCKNOW

- Russell was dispatched to Moscow in 1856 to record Tsar Alexander II’s coronation, then the following year to India, where he witnessed the ultimate recapture of Lucknow (1858). The Battle of Lucknow was fought during the Indian revolt of 1857. The British reclaimed Lucknow, which they had abandoned the previous winter after rescuing a beleaguered force in the Residency, and defeated the rebels’ organised resistance in the Kingdom of Awadh (or Oudh, as it was known in most contemporary reports).

- Skeletons still littered the streets, and the city’s domes and minars were riddled with shell holes. Nonetheless, the walls of the Red Fort, the vast Mughal palace, remained majestic.

‘I have seldom seen a nobler mural aspect and the great space of bright red walls put me in mind of (the) finest part of Windsor Castle.’- Russell wrote in his diary.

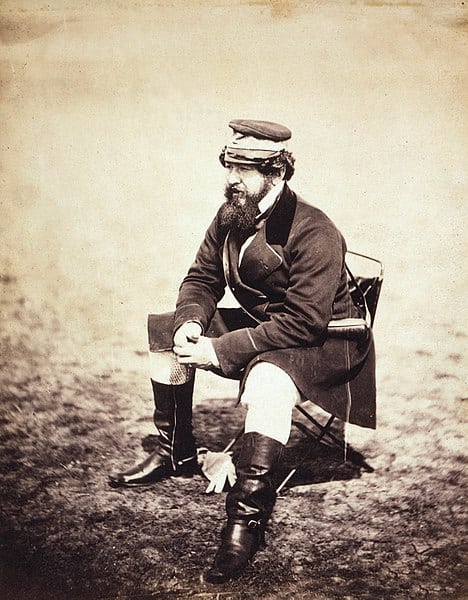

- Russell’s eventual destination, on the other hand, was far less impressive. Russell was escorted to the cell of a frail 83-year-old man accused by the British of masterminding the Great Rising, or Mutiny, of 1857, the most significant military act of resistance to Western power ever mounted anywhere on the earth.

‘He was a dim, wandering-eyed, dreamy old man with a feeble hanging nether lip and toothless gums. Not a word came from his lips; in silence he sat day and night with his eyes cast on the ground, and as though utterly oblivious of the conditions in which he was placed.... His eyes had the dull, filmy look of very old age.... Some heard him quoting verses of his own composition, writing poetry on a wall with a burned stick.’

- The prisoner was Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, the founder and first khagan of the Mongol Empire.

- Zafar was born in 1775 when the British were still a minor coastal power with three enclaves on the Indian coast. During his lifetime, he witnessed his dynasty reduced to humiliating insignificance while the British evolved from a submissive trading force into an aggressively expansionist military force.

Bahadur Shah Zafar in 1858, shortly after his trial and before his exile in Burma

What happened to Russell after his coverage of the Capture of Lucknow?

- Russell travelled west from Cork on the steamer Arabia in March 1861 to report on the American Civil War and the First Battle of Bull Run, named after a stream southwest of Washington. Russell later dispatched messages from the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and was present at the Battle of Sedan, which led to Emperor Napoleon III’s capture and the Fall of Paris. During Russell’s final campaign in 1879, he covered the Zulu War in South Africa for the Daily Telegraph. He was a prolific writer who wrote many works, including four diaries in which he captured unique glimpses of the wars he observed.

LATER LIFE AND LEGACY

- In May 1895, Russell was knighted. On 11 August 1902, King Edward VII named him a Commander of the Royal Victorian Honour (CVO), a dynastic honour bestowed by the King without the government’s intervention. During the inauguration, the King reportedly urged Russell, ‘Don’t kneel, Billy, just stoop.’

- Russell’s telegraph reports from the Crimea are his legacy. For the first time, he revealed the reality of war to readers. This reduced the gap between the home front and distant battlegrounds. They were compiled, edited and published in two volumes as The War in 1856, then amended and retitled History of the British Expedition to the Crimea in 1858.

- Russell’s battle reporting figures significantly in Northern Irish poet Ciaran Carson’s Breaking News (2003) reenactment of the Crimean battle. John Black Atkins, the Manchester Guardian’s first special correspondent, wrote Russell’s biography.

- Russell died on 10 February 1907 and is buried in London’s Brompton Cemetery.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was William Howard Russell?

William Howard Russell was a 19th-century Irish journalist widely regarded as one of the first modern war correspondents. He gained fame for reporting during the Crimean War, particularly for his work in The Times newspaper, providing detailed and often critical accounts of the conflict.

- What was Russell's significant contribution to journalism?

Russell is best known for his pioneering work as a war correspondent. He provided firsthand, vivid reports from the battlefield during the Crimean War, offering detailed accounts of the soldiers' lives and their harsh conditions. His reporting set a standard for war journalism.

- How did Russell's reporting impact public opinion during the Crimean War?

Russell's reports brought the harsh realities of war to the public's attention. His vivid descriptions of the conditions faced by soldiers, including lack of medical care and supplies, played a significant role in shaping public opinion and ultimately influenced military and government reforms.