William Pitt, the Elder Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about William Pitt, the Elder to your students?

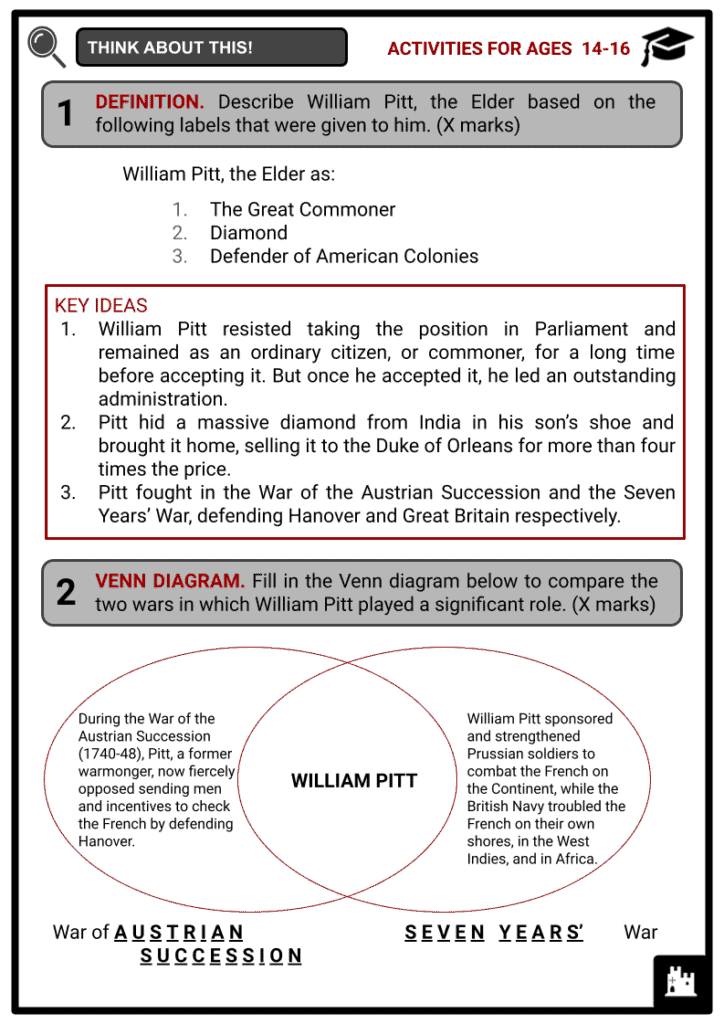

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early life

- Political career

- Contribution during the Seven Years’ of War

- Last years and death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about William Pitt, the Elder !

William Pitt, the Elder, also called the first Earl of Chatham, Viscount Pitt of Burton-Pynsent, and dubbed ‘The Great Commoner’, was a statesman whose presence and beliefs had a significant impact on British politics. He was best known as the wartime political leader of Britain in the Seven Years’ War. He died in May 1778 and was given a public funeral at Westminster Abbey. His nickname ‘The Great Commoner’ reflected the fact that he had been successful even as a ‘commoner’, before his peerage in 1766.

Early life

- William Pitt, the Elder was born on 15 November 1708 in London, England. He was from a well-known family with a long history of success in politics, both in Parliament and the colonies.

- His mother, Lady Harriet Villiers, daughter of Viscount Grandison, was from Anglo-Irish nobility while his father, Robert Pitt, was a member of Parliament, as was his grandfather, Thomas Pitt, who had been a governor of Madras.

- He attended school at Eton College from 1719 until 1726. But he hated the harshness of Eton, so he moved and studied at Trinity College, Oxford in 1727.

- Hereditary gout, which he had suffered from while still at school, forced him to leave university without a degree.

- He then continued to study for several months at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands.

- His classical education taught him to act and think in a grand Roman manner. His favourite poet was Virgil. Roman history taught him great lessons about patriotism, and Cicero, the golden-tongued orator, probably inspired him.

- His elder brother acquired the family estates, forcing William to seek alternative work. Nonetheless, he rejected the church, a younger son’s last resort as a career, and joined the military instead.

- In 1731, his Etonian friend George Lyttelton presented him to Richard Temple, the Viscount of Cobham.

- Cobham sent William on a Grand Tour of Europe, and afterwards earned him a cornetcy and a position in his horse regiment.

Political Career

- Pitt was elected to Parliament in 1735 after being awarded his brother’s ‘pocket’ boroughs in Wiltshire. He swiftly sided with Walpole’s opponents, joining Cobham’s nephews Richard Grenville and Lyttelton in the group known as Cobham’s cubs and the Boy Patriots.

- Walpole had ruled England since 1720, centralising patronage, and had grown too willing to compromise in international affairs for the sake of peace, they believed.

- The ‘patriots’ banded together with other disgruntled Whigs like John Carteret and William Pulteney to mobilise opposition forces behind Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, who was alienated from his father, King George II.

- In the 18th century, there was also no formal opposition in Parliament, and opposition to the king’s ministry was regarded as factious, if not traitorous.

- Pitt’s first speech in Parliament was so critical of the Cabinet that Walpole stripped him of his military commission.

The Battle of Fontenoy by Pierre L’Enfant. Oil on canvas. - In 1737, the Prince of Wales appointed Pitt as one of his court officials, paying him £400 per year.

- He sought to advocate for economic interests and even for colonial colonies, which were underrepresented in the Commons.

- Walpole was then deposed in 1742 and replaced by a Cabinet that comprised his old colleagues Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, and Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, with Carteret as secretary of state.

- Despite this, the Boy Patriots, of which Pitt was the recognised leader, were excluded. They fought Carteret even harder than they had Walpole.

- During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), Pitt, a former warmonger, now fiercely opposed sending men and incentives to check the French by defending Hanover.

- He denounced Carteret as a ‘Hanover troop minister’: for this, he was never forgiven by his sovereign.

- Pitt stood firm that French dominance should be resisted at sea and in its colonial territories, not on the Continent.

- When Carteret was forced to retire in 1744, Thomas and his brother Henry Pelham took over and attempted to enlist Pitt in their ministry, but George II refused.

- However, during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 (the Forty-five Rebellion), Pitt rose to prominence as the only successful statesman.

- Pitt was appointed joint vice treasurer of Ireland in February 1746 by the king, with a salary of £3,000 per year, and he became paymaster general of the soldiers two months later.

An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745, David Morier - Pitt’s friends reacted angrily, fearing he had been bought, but he went on to demonstrate his integrity as an honest but comparably poor man by pretentiously refusing to accept anything more than the official pay of more than £4,000 per year.

- He instituted numerous reforms in the administration, so while he supported the Pelhams’ alliance with Hanover, he also attempted to increase British naval power.

- Pitt anticipated promotion after Henry Pelham died in office in 1754, but after much rearrangement and intrigue, Thomas Pelham and Henry Fox (later 1st Baron Holland) abandoned him for the sake of expediency.

- He was an invalid and an old bachelor when he fell in love with Lady Hester Grenville, became engaged right away, and married in November 1754.

- After his attacks on Newcastle’s government, he was fired from the pay office in 1755, leaving him indigent.

Contribution during the Seven Years’ War

- When the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) began out in Europe, it swiftly spread to the colonies. Britain was caught off guard and, by the middle of 1757, was under threat of losing its economic entrepots in India as well as its colonies in America.

- Pitt intensified his rhetorical assault on the administration, accusing Newcastle of ineptitude.

- Military setbacks worsened and public condemnation of Newcastle grew, forcing him to retire in 1758.

- Surprisingly, George II succumbed to legislative and popular demands, allowing Pitt to join the Cabinet as secretary of state and giving him practically dictatorial control over England’s war effort.

- In November 1756, Pitt created a Cabinet that ignored Newcastle, led by the Duke of Devonshire.

- Newcastle returned to office in June 1757 with the assumption that he would control all patronage and let Pitt handle the war.

- He reactivated the militia, re-equipped and restructured the navy, and attempted to rally all parties and public opinion under a cohesive and understandable war programme.

- He focused British strategy on America and India, sending his main expeditions to America to assure the conquest of Canada and supporting the East India Company and its ‘heaven-born commander’, Robert Clive, in their war against the French East India Company.

- He sponsored and strengthened Prussian soldiers to combat the French on the Continent, while the British Navy troubled the French on their own shores, in the West Indies, and in Africa.

- This steadfast and determined campaign proved too much for Bourbon France, and under the conditions of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Great Britain retained supremacy in North America and India, preserved Minorca as a Mediterranean base, and gained territories in Africa and the West Indies.

- In 1760, George III arrived on the throne determined, as was his key adviser, the Earl of Bute, to end the war.

- Pitt resigned in October 1761 after failing to persuade his colleagues to declare war on Spain in order to prevent it from charging ahead.

Last years and death

- Pitt spent his final years gardening and suffering from gout. He referred to his gout as ‘gout in the head’ because its attacks caused him irrationalities.

- When Bute resigned in 1763, he was followed by George Grenville, and Pitt’s assaults on the government effectively ended the relationship between the two brothers-in-law.

- Pitt returned to the stage in January 1766, after being inactive in 1764 and 1765, to offer an impassioned argument for imperial liberty on behalf of the American colonists who had fought the Stamp Act and demanded its repeal.

- In July, the monarch ordered him to establish a Cabinet comprised of members from both chambers of Parliament.

The Death of the Earl of Chatham by JS Copley - Edmund Burke, his political opponent, correctly described it as a ‘tessellated pavement’.

- ‘The Great Commoner’ retreated to the Lords and lay unwell for another two years, leaving a rudderless administration to forsake his principles under the luckless Duke of Grafton and Charles Townshend.

- Pitt retreated totally and resigned from office in 1768, engulfed in a dark fit of irrationality.

- Pitt’s latter years were marred by sickness, yet he would return to the House of Lords with increasing difficulty as an elder statesman.

- His final address, against any decrease of an empire founded on liberty, marked the end of a political career committed to the synthesis of imperial authority and constitutional liberty.

- Pitt died on 11 May 1778, in the arms of his son William, who was reading him a passage from Homer’s Iliad about Hector’s goodbye.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/William_Pitt%2C_1st_Earl_of_Chatham_by_William_Hoare.jpg/330px-William_Pitt%2C_1st_Earl_of_Chatham_by_William_Hoare.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Battle_of_Fontenoy_1745.PNG/1079px-Battle_of_Fontenoy_1745.PNG?20101203115819

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/The_Battle_of_Culloden.jpg/1920px-The_Battle_of_Culloden.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/The_Death_of_the_Earl_of_Chatham_by_John_Singleton_Copley.jpg/330px-The_Death_of_the_Earl_of_Chatham_by_John_Singleton_Copley.jpg