Battle of Agincourt Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Battle of Agincourt to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background and the War Preparation

- Siege of Harfleur

- Battle of Agincourt

- Casualties and Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Battle of Agincourt!

During the Hundred Years War (1337–1453), the Battle of Agincourt was one of the most significant English victories. On 25 October 1415, the young English King Henry V led his armies to victory in northern France. The surprising English triumph over a numerically superior French army increased English morale and reputation. Following other conquests in France, Henry V was acknowledged in 1420 as the successor to the French throne and regent of France.

Background and the War Preparation

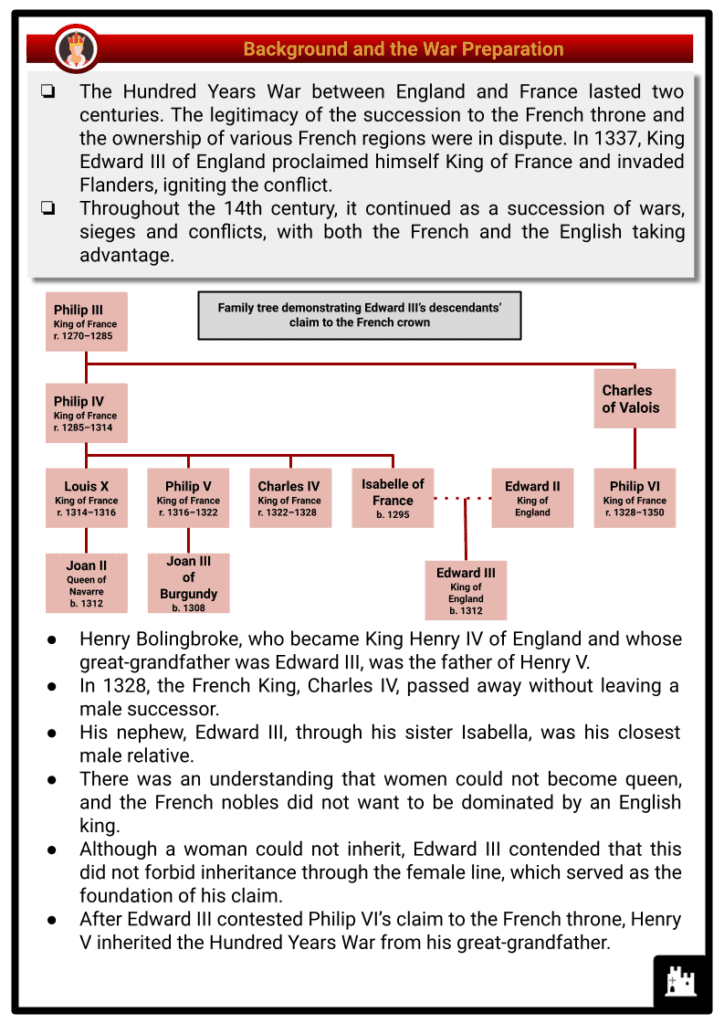

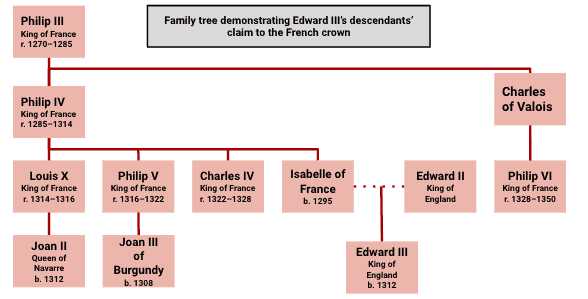

- The Hundred Years War between England and France lasted two centuries. The legitimacy of the succession to the French throne and the ownership of various French regions were in dispute. In 1337, King Edward III of England proclaimed himself King of France and invaded Flanders, igniting the conflict.

- Throughout the 14th century, it continued as a succession of wars, sieges and conflicts, with both the French and the English taking advantage.

- Henry Bolingbroke, who became King Henry IV of England and whose great-grandfather was Edward III, was the father of Henry V.

- In 1328, the French King, Charles IV, passed away without leaving a male successor.

- His nephew, Edward III, through his sister Isabella, was his closest male relative.

- There was an understanding that women could not become queen, and the French nobles did not want to be dominated by an English king.

- Although a woman could not inherit, Edward III contended that this did not forbid inheritance through the female line, which served as the foundation of his claim.

- After Edward III contested Philip VI’s claim to the French throne, Henry V inherited the Hundred Years War from his great-grandfather.

- As his great-grandfather Edward III had done, Henry V desired to reestablish English claims to the throne of France and authority over French possessions.

- France was in the middle of a civil war, and military action against an external foe would help solidify Henry’s position as king and improve the devotion of his countrymen.

- The King called a Great Council and gathered influential nobles and prelates and announced his plan to lead an army into France. However, the Lords urged that he continue negotiations.

- During the subsequent negotiations, Henry stated that he would forfeit his claim to the French throne if the French paid the outstanding ransom of John II (who had been captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356) and conceded English ownership of Anjou, Brittany, Flanders, Normandy and Touraine in addition to Aquitaine. Henry would wed Catherine, the young daughter of Charles VI, and receive a dowry of two million crowns.

- The French countered with what they believed to be generous marriage terms for Catherine: 600,000 crowns in dowry and an expanded Aquitaine. By 1415, discussions had ceased, with the English saying that the French had insulted their claims and Henry himself.

- Henry once more requested permission for war with France from the Great Council on 19 April 1415, and this time they approved.

War Preparation

- The invasion entailed a large number of troops, weapons and hundreds of ships, none of which were inexpensive. Henry convinced Parliament to impose additional taxes and borrowed vast sums from rich English residents and cities to support his quest.

- London alone loaned him almost 5 million in current dollars. As a guarantee of repayment, Henry presented his supporters with a variety of royal treasures, including jewels, a gold collar known as the ‘Pusan d’Or’, and a crown adorned with rubies and diamonds that had belonged to King Richard II.

- The majority of the troops in late medieval England’s army were professionals serving under contract.

- The monarch, a nobleman or even a squire might enter into a formal agreement (an indenture) with a second party, establishing rules for military duty in exchange for a certain salary.

- These stipulations typically comprised the number of men-at-arms (heavily armed troops mounted on horses) and archers (mounted or on foot and principally armed with longbows) to be recruited, the period of service, and confirmation of the daily pay rates.

- A record of an agreement of war was signed by the Crown and Sir James Haryngton on 29 April 1415.

- Sir James’ indenture stated that he and his soldiers were to receive the period’s standard daily pay rates, which were two shillings for himself, twelve pence for each man-at-arms, and six pence for each archer.

Siege of Harfleur

- On 11 August 1415, Henry set sail from Southampton with a force of around 12,000 troops, which reportedly comprised 1,500 ships. Three days later, they reached the northern French coast and began their campaign by moving his army to the Seine’s mouth and besieging the strategically significant city of Harfleur.

- The King anticipated the town would fall within a few days, but the siege lasted five arduous weeks, during which at least one-third of his army perished or were crippled due to dysentery.

- The city surrendered on 22 September, and the English troops did not withdraw until 8 October.

- The time it took to seize Harfleur, and the strain of disease on Henry’s forces negatively impacted his plans to invade France. He made the decision to send his troops, roughly 9,000 of them, to the English-controlled port city of Calais.

Siege in Harfleur - Moving to Calais had been challenging for Henry’s troops. Firstly, it was 250 kilometres from Harfleur. Secondly, it required overcoming several natural barriers, the River Somme being the most significant. Thirdly, the men were weary and had nothing to eat. Finally, the French army had also started its move.

- After Henry V’s march to the north, the French advanced along the River Somme to obstruct his path.

- They were initially successful, compelling Henry to travel south, away from Calais, in order to locate a ford.

- The English eventually crossed the Somme south of Péronne, near Béthencourt and Voyennes, and began their march northwards.

- On 24 October, a sizable French army under the command of the Constable Charles d’Albret and the marshal Jean II le Meingre (known as Boucicaut) were able to catch him close to the hamlet of Agincourt as a result of the delay.

- The French hesitated to initiate a conflict. They followed Henry’s army while issuing an appeal to aristocrats in the region to join the army.

- Both forces were poised to fight, but the French refused, anticipating the arrival of more soldiers.

- The two armies spent the night of 24 October on open ground.

Battle of Agincourt

- Most historians think that only 6,000 to 9,000 Englishmen fought against a French army of between 12,000 and 30,000 during the Battle of Agincourt.

- Fearing an ambush by his much bigger foe, Henry V maintained discipline in his ranks by ordering 24 October to pass in complete stillness and silence.

- Knights and men-at-arms were informed that defying the command would result in the loss of their mount and equipment. Meanwhile, the lower rank were threatened with losing their right ear.

- On 25 October, Henry led the English troops into the battle of Agincourt. A bigger French army was headed by the French Marshal Boucicaut and the French Constable Charles D’Albret.

- Henry’s army at Agincourt likely numbered 5,000 to 8,000 knights, men-at-arms and archers. The French army’s strength is estimated to be somewhere between 15,000 and 30,000 soldiers.

- The English and Welsh archers were armed with the English longbow, a weapon renowned for its lethal range. Archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets, and war hammers for hand-to-hand combat.

French and English army - King Henry donned a bascinet helmet adorned with a gold crown and polished plumes. The flags of England and France were embroidered on his overcoat.

- The army was divided into three sections, with the right wing commanded by Edward, Duke of York, the centre by the King himself, and the left wing by the elderly and seasoned Baron Thomas Camoys. Sir Thomas Erpingham was the leader of the archers. Hundreds of sharply pointed stakes protruded from the English positions. The English deployment somewhat resembled a crescent shape.

- The Dukes of Alençon and Edward III, Duke of Bar led the main battle. The French army was dominated by highly armoured mounted and foot met-at-arms. Crossbowmen were there, but they were relegated to the rear.

- There were three mounted special detachments: two to eliminate the English archers on the wings, and one to rally the natives and distract the enemy by attacking the baggage train.

- The English military tactic was to wait for the French to charge, at which point the archers would snipe them to bits and the dismounted men-at-arms would finish them off. However, the French army did not move, so Henry made the decision to advance.

- Sir Thomas Erpingham gave the archers the signal. They removed their stakes from the ground, and Henry’s entire army, maintaining its crescent formation, moved to within around 250 metres of the enemy. From this distance, the longbows were dangerous.

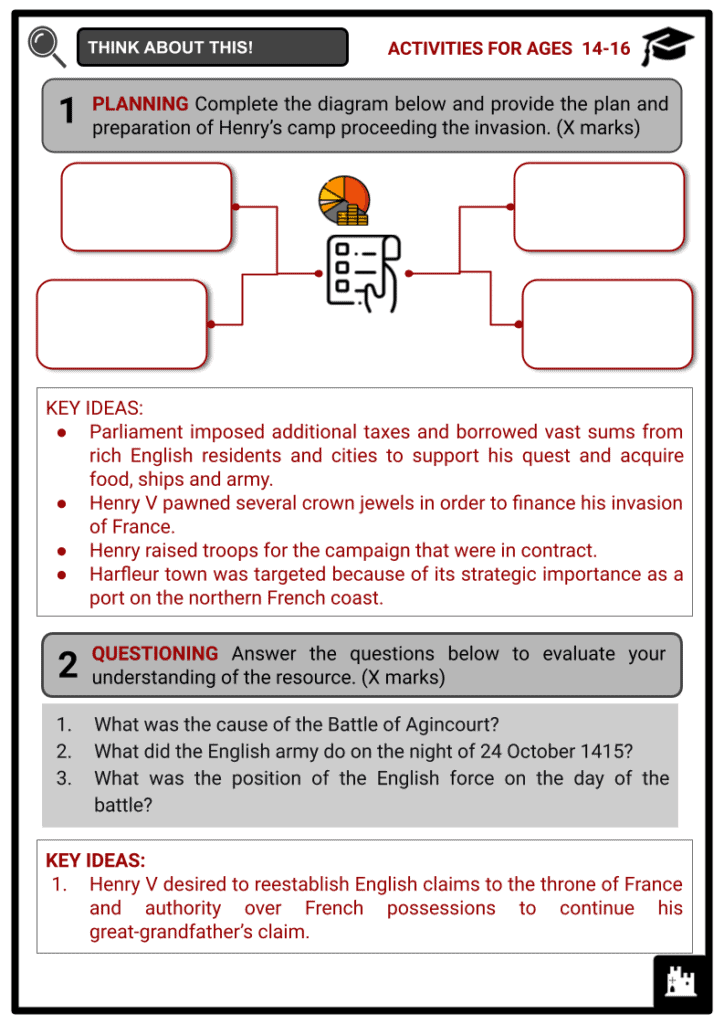

- The French were caught off guard: men hurried for their weapons and horses. The French charged towards the longbowmen, but, due to the muddy ground, they were unable to flank the longbowmen. When the French cavalry and infantry rushed the English position, the archers unleashed a hail of arrows, and the horses were mowed down.

- The remaining French infantry reached the front of the English line and forced it back, while the longbowmen on the sides continued to fire at point-blank range. As soon as the archers ran out of arrows, they abandoned their bows and attacked the disorganised, exhausted and injured French soldiers arrayed in front of them with hatchets, swords, and the mallets they had used to drive in their stakes.

- The second line of French troops had joined the attack, but they too had been unable to make much headway due to the terrain’s confinement.

- Henry, according to contemporary English chronicles, engaged in hand-to-hand combat. Upon learning that his younger brother Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, had been wounded in the groin, Henry took his household guard and stood over his brother until he could be brought to safety.

- Despite the deaths of the Duke of York, the Duke of Gloucester, and Henry himself, the French were being massacred in vast numbers. The brother of the Duke of Burgundy, the Duke of Brabant, arrived with a small number of troops, only to be arrested.

- The lone French triumph was an assault on a poorly defended English baggage train. Ysembart d’Azincourt, a local knight, with a small number of men-at-arms and varlets and roughly 600 peasants, attacked the English baggage train and stole some of Henry’s personal goods, including a crown.

- The battle lasted almost three hours, but the commanders of the second line were finally slain or captured, just as the leaders of the first line had been.

- After the initial English triumph, Henry was frightened to discover that the French were gathering for a second assault. During the brief panic, Henry ordered the execution of thousands of French captives, with only the highest-ranking ones spared. It appears to have been a choice made alone by Henry, as the English knights considered it contradictory to chivalry and against their interests to execute wealthy captives for whom it was customary to demand compensation. Henry vowed to execute

anyone who disobeyed his demands.

Casualties and Aftermath

- The battlefield was undoubtedly the most influential factor in determining the outcome. Due to its narrowness and the heavy mud that the French knights had to traverse, the newly tilled terrain surrounded by thick woods favoured the English. Recent heavy rains rendered the battlefield extremely muddy, making it difficult to traverse in full plate armour.

- Following the victory at Agincourt, King Henry continued his march to Calais and then came home to England for the celebrations and hero’s welcome. His troops remained at Calais, but it was too late in the season for further campaigning. For the moment, Harfleur became an English town.

- The defeat at Agincourt cost France between 5,000 and 10,000 killed and captive soldiers, including many of France’s most important nobles. This included three dukes, five counts and ninety barons.

- Charles d’Albret, Constable of France, died, while the renowned Boucicaut, Marshal and national hero of France, was incarcerated. The dukes of Orleans and Bourbon were held as captives. France was consumed with recrimination.

Laurence Olivier stars as Henry V - The English likely lost around 500 soldiers, as well as the Duke of York, Earl of Suffolk and Daffyd Gam.

- Henry’s success made it simpler for him to subsequently conquer Normandy since the French were hesitant to engage him in another fight.

- However, rather than only being the consequence of military might, his final victory in May 1420 — acceptance as heir to the French throne and as regent of France by the Treaty of Troyes — was brought about by political strife in France.

- Shakespeare’s Henry V, written in 1599, has the most well-known representation of the fight in popular culture.

- The drama explores the difficulties of being king, including the conflicts between projecting an image of being chivalrous, honest and righteous and becoming as Machiavellian and ruthless as circumstances

demand.