Henry III of England Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Henry III of England to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life and Personal Life

- Conflicts during Henry’s Reign

- Rise to Fame

- Political Crisis

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Henry III of England!

Henry III, also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England from 1216 to 1272, during which time he faced a revolt by English barons over issues of royal power and baronial misgovernment. He assumed the throne at the age of nine and his early rule was dominated by advisers Hubert de Burgh and Peter des Roches. He attempted to reconquer French provinces but the campaign failed and resulted in a revolt led by William Marshal’s son Richard. The conflict was ultimately resolved through a peace settlement negotiated by the Church.

EARLY LIFE AND PERSONAL LIFE

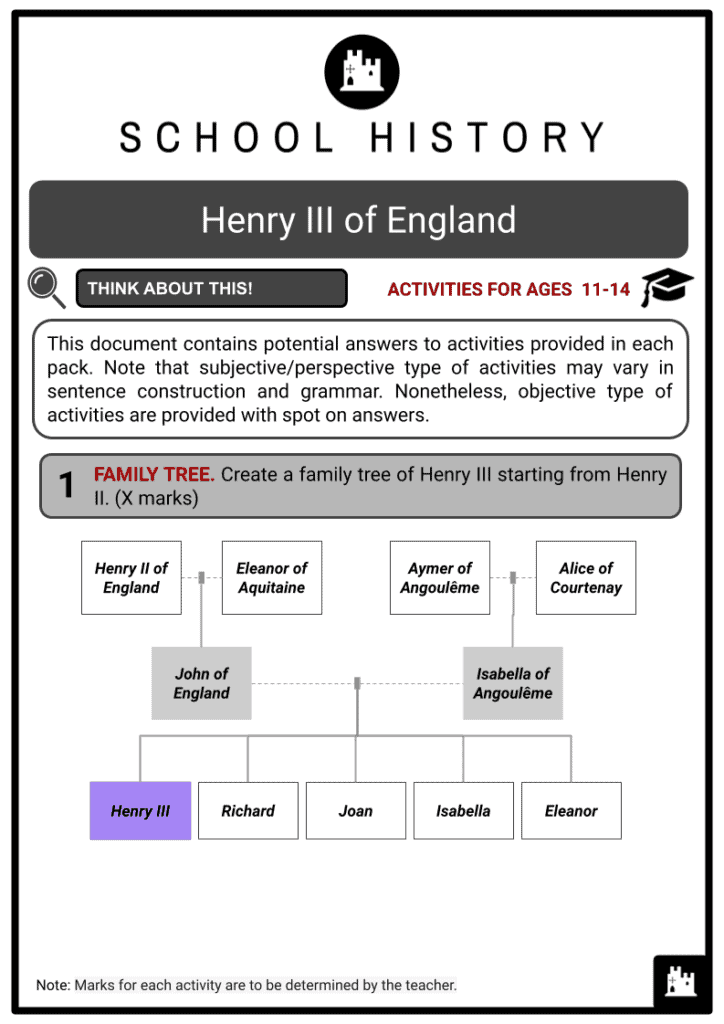

- Civil war gripped England following the failure of the Magna Carta in 1215. The rebel barons were aided by the French king’s son, Louis, who was claiming the English throne for himself. The war soon reached a stalemate. This was the situation in England when the last Angevin king, John, became ill and died in 1216. John left the nine-year-old Henry as his heir.

- Henry III inherited the throne at a difficult time, with much of his realm occupied by rebel barons and supporters of Louis, and most of his father’s possessions under French control. However, he had support from loyalist leaders and the papal legate and was crowned at Gloucester Cathedral in October 1216 to reinforce his claim to the throne. The Council of Thirteen worked to rally support for his claim.

- Henry III, in his youth, considered several potential marriage partners but ultimately married Eleanor of Provence in 1236. She was the second daughter of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence, and well-mannered, cultured and articulate. The couple married at Canterbury Cathedral and she was crowned queen at Westminster in a lavish ceremony. While Eleanor did not bring any land with her, her family’s connections throughout Europe made her a wise choice for the king:

- Her sister was married to Louis IX of France

- Her mother’s family controlled the entry point to northern Italy

- Her family was connected to the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire

- Her uncles were skillful diplomats

Coronation of Henry III

- Henry III and Eleanor’s marriage was a happy one, despite the age gap between them. The union brought many Savoyard relatives to England, who were given patronage and political influence by Henry III, and many were also married into the English nobility. This caused divisions among the English nobility as these foreigners became the dominant group in the royal court, but the marriage did successfully provide Henry III with heirs. However, it did not bring any territorial gains for the Crown.

CONFLICTS DURING THE REIGN

- While Henry III had first assumed power in 1227, it was only after the dismissal of Peter des Roches and his supporters that the king ruled England personally, making several significant changes in royal government. The period between 1232 and 1258 was one of apparent domestic peace. It also witnessed Henry III as a king in his own right.

- The post of justiciar was left vacant, turning the position of chancellor into a more junior role.

- A small royal council was created, in which appointments, patronage and policy were decided personally by the king and his immediate advisers.

- Those outside the king’s inner circle found it difficult to influence policy or to pursue legitimate grievances, particularly against the king’s friends.

- In 1226, Louis VIII died and left the French throne to his 12-year-old son, Louis IX, who faced threats from several French barons and revolts across the country. In 1227, Henry III took control of his government and planned to invade and reclaim his Angevin inheritance, but instead proceeded slowly south to Bordeaux in 1230. As he decided to avoid open battle with the French by not invading, perhaps on the advice of his justiciar, his campaign failed:

- Henry III failed to advance to Normandy and rally the support of the local barons.

- Henry III failed to seize towns or gain the allegiance of his mother or her new husband, Hugh de Lusignan.

- In 1230, Henry III returned to England after a failed campaign to retake the Angevin lands from France. The blame for the failure was put on Hubert de Burgh, who was arrested and imprisoned by Peter des Roches. This led to complaints from barons and a rebellion in 1232.

- In 1234, Peter des Roches led armies into Richard Marshal’s lands in Ireland and South Wales, causing Richard to ally with Prince Llywelyn and take Glamorgan. This led to a rebellion in England. Henry III was unable to gain a clear military advantage and feared that Louis IX of France would take advantage and invade Brittany. The Archbishop of Canterbury intervened and threatened the king with excommunication unless he dismissed Peter des Roches and his associates. The rebellion was settled in May 1234 at Gloucester and the king was praised for his humility in accepting a slightly embarrassing peace.

- The terms of the agreement included the following:

- Henry III received the rebels back into allegiance.

- Gilbert Marshal, Richard’s younger brother, succeeded to the family estates.

- Some land seizures were reversed.

- Henry III vowed to consult with councils.

- Some rebel barons were restored to their estates.

- Meanwhile, England’s truce with France finally ended. Fresh conflict between the French king and Henry III’s allies in France broke out and Brittany fell to Louis IX in November.

RISE TO FAME

By 1258, Henry III’s rule had grown increasingly unpopular as a result of various endeavours and overseas policies the king had pursued.

War with France

- The Saintonge War in the early 1240s provided an opportunity for Henry III to regain the Angevin possessions lost during his father’s reign. The conflict arose from discontent among vassals of Louis IX in Poitou over the naming of Alphonse, the French king’s brother, as Count of Poitou instead of Henry III’s brother, Richard of Cornwall.

- The Poitevin nobility, led by Hugh X of Lusignan, formed a confederacy against the French king due to his increasing control over their demesne. Count Alphonse of Poitiers rallied loyal nobles and Louis IX assembled a large force to defeat the rebel Poitevins. Henry III and Richard of Cornwall joined the French rebel force, but the French defeated them at the Battle of Taillebourg and Henry III fled to Saintes and eventually withdrew to Bordeaux. Hugh X also surrendered, Louis IX confiscated and sold his castles and Henry III was forced to ask for a five-year truce by March 1243, as his focus shifted to European politics.

The Lusignans

- The failure of Henry III and the French rebels at the Saintonge War prompted the departure of the Lusignans from France. Some of them arrived in England in 1247 and were warmly welcomed by the English king. His generosity towards the Lusignans caused widespread resentment and contributed to the growing anger towards foreigners in the kingdom.

- Henry III began granting favours to the Lusignans and rewarding them with castles and manors.

- The Lusignans were resented for their harsh rule. In fact, they sometimes resorted to violence in solving disputes.

- The English king appeared willing to violate the Magna Carta in support of his favourites.

- Legal protection was often given to the Lusignans as their wealth proved useful to the Crown.

- Since the Lusignans enjoyed royal patronage, they had regular access to the king, which meant they had a huge impact on policy and influence over many of Henry III’s autocratic ideas.

- In essence, the considerable power and the attitude of the Lusignans in England was resented in the kingdom, thereby contributing to the growing unpopularity of Henry III.

Rebellion in Gascony

- In 1252, Henry III was forced to deal with a violent uprising in Gascony caused by the harsh policies of his lieutenant, Simon de Montfort. Simon de Montfort, a French noble, rose to power in England, gaining the earldom of Leicester in 1236 and becoming the royal lieutenant of Gascony in 1248. He was given freedom of action in Gascony, but his confiscation of land and destruction of buildings caused a rebellion and opportunity for neighbouring Castile to assert claim to the region. The English court was split on the crisis, with Simon and his wife Eleanor blaming the Gascons, while Henry III blamed Simon’s misjudgement and instituted an inquiry.

- The trial of Simon further damaged the relations between the barons and Henry III.

- Simon was formally acquitted on the charges of oppression and was forced to retire to France.

- Henry III’s relationship with his sister became strained because of this.

- To suppress the rebellion in Gascony, the English king organised an expensive campaign to stabilise the province: he personally went to the region, took castles and granted expensive rewards.

- Alfonso X signed a treaty of alliance. Gascony was then given to Henry III’s son Edward, following Edward’s marriage to Alfonso X’s half-sister.

- The expensive campaign left Henry III heavily in debt and dependent on loans from his brother Richard and the Lusignans.

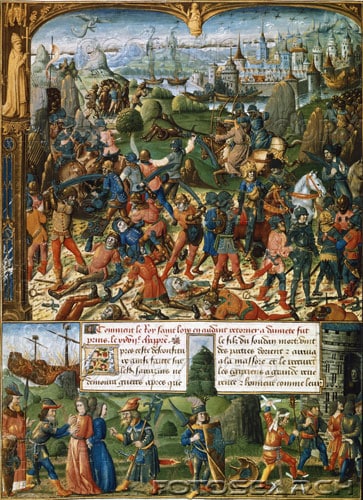

7th Crusade

Problem of Crusading

- In the 13th century, crusading was a popular cause and both Henry III and Louis IX took crusading vows. After the fall of Jerusalem to the Khwarezmian clans in 1244, Henry III planned to undertake his own crusade to the Levant by arranging passage, imposing crusading tax and planning for transportation. However, due to costly problems in Gascony, Henry III’s crusade failed to launch. But he did not give up on his hopes for a crusade.

Sicilian Affair

- In 1250, after the death of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, Pope Innocent IV sought a new ruler for Sicily and Henry III saw an opportunity to acquire it for his son Edmund. The Pope agreed and urged Henry III to send an army led by Edmund to reclaim Sicily and offered to contribute to expenses. However, Pope Innocent IV was later replaced by Pope Alexander IV, who invested Edmund as ruler of the Kingdom of Sicily in 1255.

- Henry III attempted to regain Sicily through a deal with Pope Alexander IV in 1255, but his efforts were met with resistance from parliament and the English barons. He was unable to raise enough money to pay the papacy for the expenses of the campaign and was threatened with excommunication. The grant of Sicily to his son Edmund was revoked and the English barons and Church felt the money spent was wasted.

POLITICAL CRISIS

- In 1258, English barons led by Simon de Montfort revolted against Henry III’s personal rule, citing issues with officials raising funds, foreign influence at court and failed overseas policies. They forced the king to accept a panel of barons and clergymen to govern in place of personal rule. Henry III, in a vulnerable position, agreed to the reforms.

- The barons demanded that:

- Henry III and his heir Edward were to be bound by a panel of 24 barons and clergymen.

- The panel was to be chosen by the king and the barons, each side choosing 12 men.

- The king was not to impose taxes.

- Henry III was to hand over the royal seal.

- The panel would elect a council of 15 to aid the king.

- Parliament would meet three times a year.

- In 1258, barons led by Simon de Montfort and Richard de Clare created an alliance, removed the Lusignans from court, and forced King Henry III to accept a series of reforms, known as the Provisions of Oxford, aimed at addressing issues of local and central government and baronial misgovernment. Henry III attempted to exploit the terms by nominating Lusignans to the panel, but in October 1259, the terms were further developed with the Provisions of Westminster.

- A Council of Fifteen was established, which was made up of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Bishop of Worcester, six earls and seven barons. The council would choose the king’s chief ministers. The chancellor could not seal charter or writs without permission of the council. Parliament, consisting of barons and knights or county, was to meet three times a year.

- Provisions to oversee the great officials of the kingdom:

- The justiciar was given extensive powers to implement reforms, to hear complaints and dispense justice.

- The treasurer and chancellor were to hold office for only one year.

- The treasurer would be required to render accounts.

- The chancellor could only seal ordinary writs without consent and could make no major grants.

- Pressure from the lesser barons and the gentry present at Oxford also helped to push through wider reform reflected in the Provisions of Westminster, aimed at limiting the abuse of power by both Henry III’s officials and the major barons.

- The Provisions sought to address many of the grievances that had developed during Henry III’s personal rule, particularly the following:

- The king’s failures to consult with the barons

- The financial problems of the country

- The maldistribution of patronage

- Henry III’s government implemented the Provisions of Oxford and Westminster, which limited the king’s power and created a council of barons and clergymen to govern alongside him. This council, known as the Council of Fifteen, held more power than the king and became the effective governing body of the kingdom. This marked the first time that a king was placed under baronial control in England.

- Changes implemented in the local government:

- Sheriffs were to hold office for only one year.

- They were to become county knights.

- They were to receive an annual salary or allowance.

- They had to render accounts.

- They were not allowed to accept bribes.

- Four knights in each shire were to investigate abuses by royal officials.

- The barons sought to prevent mistreatment and corruption by sheriffs and established a salary to deter exploitation of the office. However, these changes proved unworkable and were further developed in the Provisions of Westminster in 1259. Henry III’s personal rule was marked by both royal and baronial misgovernment and the Provisions of Oxford failed to address barons’ issues. In 1259, the Ordinances of the Magnates were issued to prevent obstruction of complaints against barons and bailiffs and to grant rights to their men, enforced by the justiciar. The Provisions of the Barons and Westminster were also issued to limit barons’ ability to bring cases to court and address the problem of summoning tenants to attend court, placing the barons under the same restrictions as the king.

- One of the aims of the new regime had been to settle the long-running dispute with France. In order to achieve this, Henry III and at least six members of the Council of Fifteen, including Simon de Montfort, left for Paris in 1259 to negotiate the final details of a peace treaty with Louis IX. Under the Treaty of Paris (1259):

- Henry III acknowledged the loss of the Duchy of Normandy.

- Henry III agreed to renounce all claims to the Angevin Empire.

- Henry III was confirmed as the legitimate ruler of Gascony, but only as a vassal to Louis IX.

- Henry III agreed to pay the French king 15,000 marks and supply 500 crusading knights for two years.

- Louis IX withdrew his support for English rebels.

- Supported by Eleanor, Henry III decided to stay in France, perhaps to conclude the arbitration over money owed to him under the 1259 treaty and also because of his poor health. His decision to remain in France began to highlight divisions among the barons and led to political manoeuvring.

- In April 1260, Simon de Montfort returned to England and reasserted royal authority independently of the barons. Conflict broke out between Richard de Clare’s forces and those of Simon and Edward, but Richard intervened and prevented a military confrontation. Simon was put on trial, and a compromise was reached with Richard de Clare, but it soon broke down. Henry III failed to maintain control and the baronial council collapsed into chaos by the end of the year. He secretly sought absolution from his oath to the Provisions and tried to settle personal grievances with Simon in an attempt to weaken his position. He then drafted his grievances against the baronial council, including:

- The worsening financial situation

- The collapse of impartial justice

- Council meetings held in his absence

- Loss of royal power and dignity

- The quality of officials appointed by the council

- Henry III attempted to use the Treaty of Paris to improve his financial position but his attempts to settle the crisis permanently by force failed. He resumed unpopular policies and failed to address baronial and royal abuse of Jewish debts, which led to a weakened royal government, further incursions in Wales and financial problems. By 1263, Henry III’s authority had collapsed and England was headed towards civil war.