Download Hundred Years’ War Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Hundred Years’ War to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

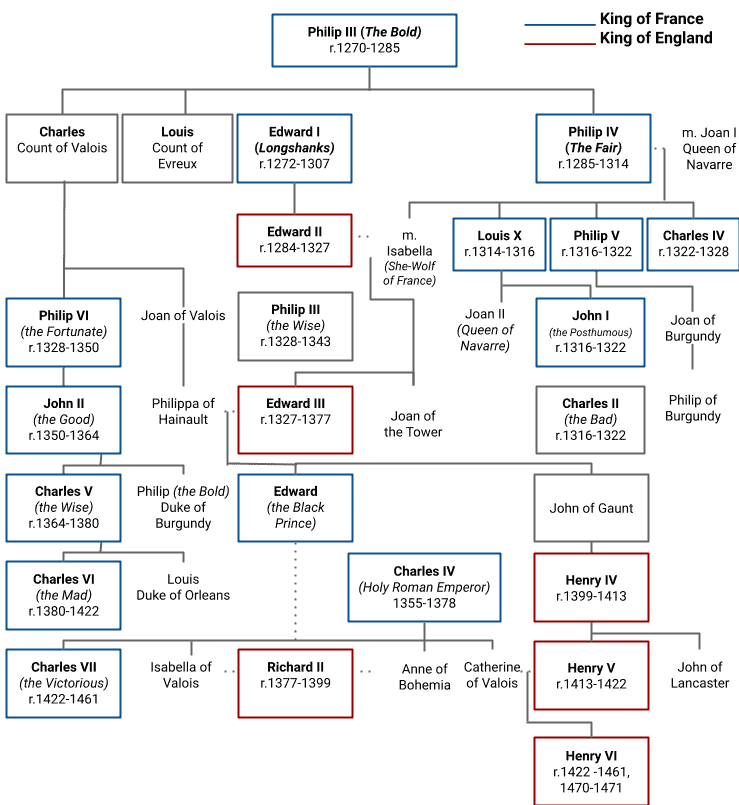

- English and French Royal Houses during the Hundred Years’ War

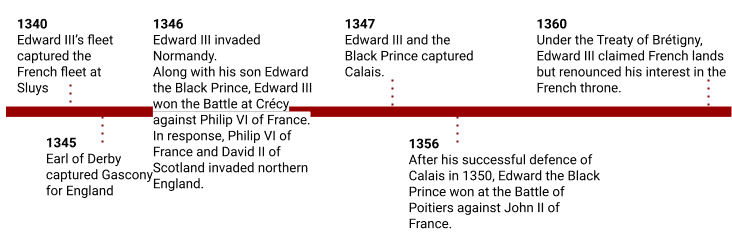

- Timeline of Significant Events

- The Edwardian War

- The Carolingian War

- The Lancastrian War

- Impact of the Hundred Years’ War

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Hundred Years’ War!

- Historians adopted the term ‘Hundred Years’ War’ as a means to periodise all the events that culminated in the longest military conflict in European history (1337 to 1453). The conflict drew in many allies of the English House of Plantagenet against the French House of Valois over the right to rule the kingdom of France and the issue of sovereignty.

- The Hundred Years’ War was a series of conflicts from 1337 to 1453 (it actually lasted 116 years). The battle spanned five generations of kings and two rival dynasties over the largest kingdom in Western Europe. Over and above warfare, the people endured famine and plague. On the other hand, nationalism gained new momentum and fervour. England dominated for decades, but victories see-sawed.

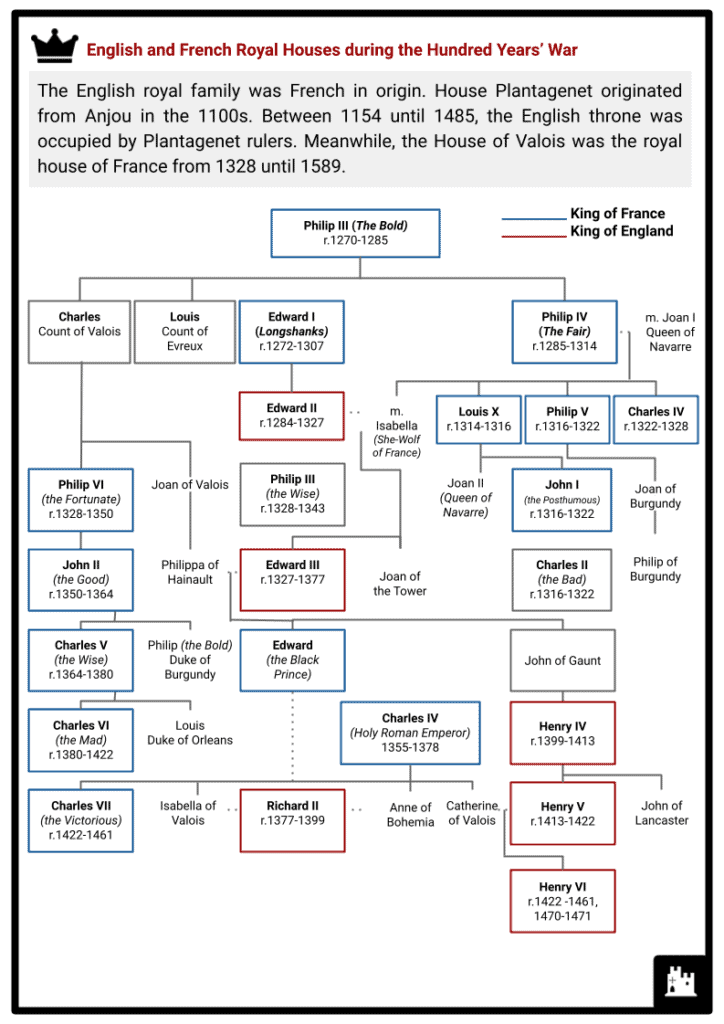

English and French Royal Houses during the Hundred Years’ War

- The English royal family was French in origin. House Plantagenet originated from Anjou in the 1100s. Between 1154 until 1485, the English throne was occupied by Plantagenet rulers. Meanwhile, the House of Valois was the royal house of France from 1328 until 1589.

Timeline of Significant Events

- The Hundred Years’ War is commonly divided into three phases: The Edwardian (1337-60); The Caroline War (1369-1389); and The Lancastrian War (1415-1453). It was separated by several truces and fought by five generations of monarchs from two rival dynasties.

The Edwardian War (1337-1360)

- The French origin meant much land and many titles were held by the English.

- As per fiefdom, having French titles meant being vassal to the king of France – a major source of conflict.

- The size of English land ownership in France varied over the years, sometimes dwarfing that of French ownership.

- France would strip away land, wealth and titles from England where opportunity arose in order to keep the growth of England in check.

- This especially happened when England was at war with Scotland, an ally of France. But by 1337, only Gascony in France was held by England.

- Edward III (reigning England from 1327) experienced ongoing conflict with Scotland. Philip VI of France allied with Scottish King David II. Edward III knew he couldn’t fight a war on two fronts. In retaliation, Edward III provided refuge for French fugitive Robert III of Artois.

- Refusing to expel Robert III, Philip VI confiscated Edward III’s French Duchy of Aquitaine.

- Edward III responded by reasserting his claim to the French throne. Conflict ensued from 1337 to 1360. However, Edward III’s alliances didn’t measure up to France’s. He experienced no real victories in the early stages other than a naval victory at Sluys in June 1340, which secured English control of the Channel.

- Meanwhile, discontent grew back home in England, created by debt and financial pressure from the war. By 1340, Edward III returned to England and purged his administration. Instability continued, however.

- New limitations were imposed on English monarchs who were given defined duties and limits. Come July 1346, Edward III staged a major offensive in Normandy with 15,000 men and met up with English forces in Flanders. The 35,000-strong army dominated the Battle of Crécy.

- Having lost the Battle of Crécy and Calais to England, the Estates of France refused to fund Philip VI’s plan to counter-attack and invade England.

- By 1348, the Black Death was sweeping through England and France wiping out over a third of the population.

- The epidemic killed millions, creating labour shortages and impacting wages and inflation.

- Both Philip VI and Edward III concentrated on stabilising their countries and ceased conflict. Military operations in France only resumed on a large-scale in the mid-1350s.

- Philip VI died in 1350 and was succeeded by his son, John II. In 1356, Edward III’s eldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, fought and won the Battle of Poitiers. He captured King John II and his son Philip.

- England enjoyed a series of victories and held large swathes of France. The French king was in custody and the French government nearing collapse in his absence.

- Proposed by England and accepted by France, the Treaty of London followed the Black Prince’s resounding victory at Poitiers. In the terms, England was permitted to annex its lands (Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Aquitaine) within its ancient limits of Calais and Ponthieu, and was given independence rather than the fiefdom of the Duchy of Brittany.

- In addition, France would pay a ransom of three million écus for John II’s release. The French Estates-General rejected the treaty, stating too much territory was being relinquished.

- Edward III launched a fresh invasion. His weak army led him to reopen negotiations, however.

- This was a truce signed between King John II of France and Edward III of England on 8 May 1360.

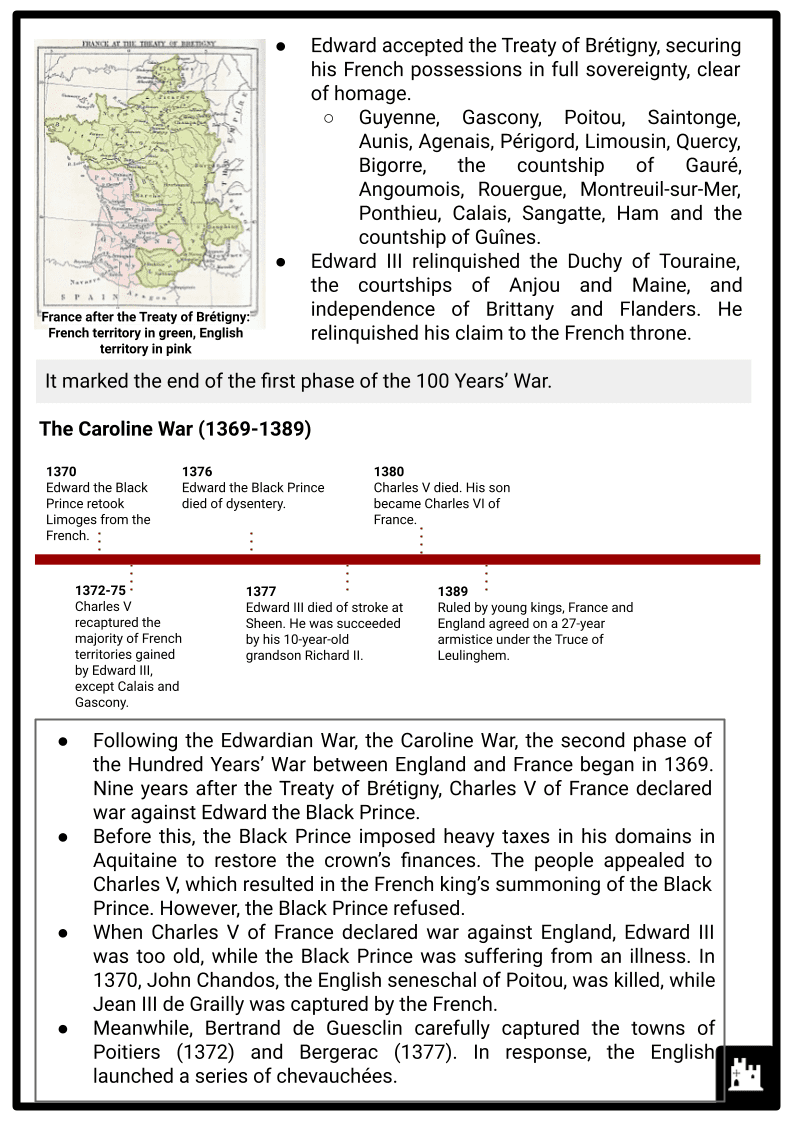

- Edward accepted the Treaty of Brétigny, securing his French possessions in full sovereignty, clear of homage.

- Guyenne, Gascony, Poitou, Saintonge, Aunis, Agenais, Périgord, Limousin, Quercy, Bigorre, the countship of Gauré, Angoumois, Rouergue, Montreuil-sur-Mer, Ponthieu, Calais, Sangatte, Ham and the countship of Guînes.

- Edward III relinquished the Duchy of Touraine, the courtships of Anjou and Maine, and independence of Brittany and Flanders. He relinquished his claim to the French throne.

The Caroline War (1369-1389)

- Following the Edwardian War, the Caroline War, the second phase of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France began in 1369. Nine years after the Treaty of Brétigny, Charles V of France declared war against Edward the Black Prince.

- Before this, the Black Prince imposed heavy taxes in his domains in Aquitaine to restore the crown’s finances. The people appealed to Charles V, which resulted in the French king’s summoning of the Black Prince. However, the Black Prince refused.

- When Charles V of France declared war against England, Edward III was too old, while the Black Prince was suffering from an illness. In 1370, John Chandos, the English seneschal of Poitou, was killed, while Jean III de Grailly was captured by the French.

- Meanwhile, Bertrand de Guesclin carefully captured the towns of Poitiers (1372) and Bergerac (1377). In response, the English launched a series of chevauchées.

- John of Gaunt was the third son of Edward III of England. While the Black Prince became incapacitated to rule the kingdom, John of Gaunt assumed control of some parts of the government.

- In 1373, John of Gaunt launched the Great Chevauchée, which aimed to raid lands in France from Calais up to Bordeaux.

- However, the English military campaign faced financial difficulties because of the Black Death in 1369.

- The chavaucée or war-ride was a warfare that involved the burning of manors and villages within the enemy’s lands. The chevauchée was successfully used by Edward III and the Black Prince during the Edwardian Wars but not during the Caroline War.

- When the English forces attempted to cross the Loire and Allier rivers, the French, led by Olivier de Clisson, ambushed them. By the time John of Gaunt’s forces reached Bordeaux, many were half-starved. This defeat resulted in resentment in England.

- Instigated by Pope Gregory XI, the Treaty of Bruges was signed between England and France in 1375. It was signed in Bruges (present-day Belgium) by Philip II, Duke of Burgundy and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. However, the war resumed two years later after both factions failed to agree on sovereignty issued over Aquitaine.

- In 1376, the Black Prince died. The following year, while attempting to reconcile with France, Edward III of England also died.

- Young Richard of Bordeaux succeeded the throne before he was deposed by Henry Bolingbroke, his cousin from the House of Lancaster.

- In 1380, Charles V of France died and was succeeded by his underaged son, Charles VI.

- In 1389, a truce was declared between both young monarchs. On 12 March 1396, relations further improved when Richard II of England married the daughter of Charles VI of France, Isabella. Their union cemented a two-decade peace between the two kingdoms.

- When Henry IV became king, England was preoccupied with rebellions within England and Wales.

The Lancastrian War (1415-1453)

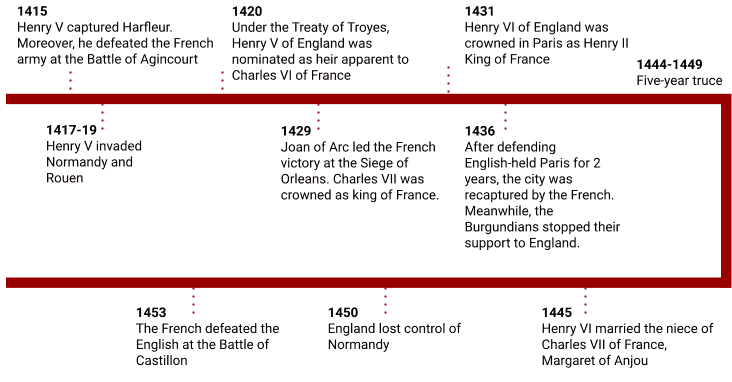

- Long peace between England and France followed after the Caroline War. However, it was interrupted in 1415 when Henry V of England insisted on his right to the French throne. The final phase of the Hundred Years’ War was the Lancastrian War, which began at the Battle of Agincourt.

- Henry V was the son of Henry (Bolingbroke) IV of England, who usurped the throne after murdering Richard II. Henry IV was the son of John of Gaunt and grandson of Edward III. Henry V believed that success in wars was a way to legitimise his reign.

- In 1415, Henry V led his forces to Normandy and captured the port of Harfleur. After winning the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415, Henry V’s forces captured Caen in 1417. By 1419, the English conquered all of Normandy, including Rouen.

- The series of French defeats convinced the nobility in France to sign a treaty. In May 1420, the Treaty of Troyes, which nominated Henry V as the regent and heir to Charles VI, was signed. In the same year, Henry V married Catherine of Valois, Charles VI’s daughter. Conflict ensued between the Burgundians and Dauphin Charles (the disinherited heir of Charles VI).

- In March 1421, Henry V’s brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, was killed at the Battle of Baugé. In response, Henry V returned to France and captured Meaux in May 1422.

- On 31 August 1422, Henry V failed to continue his military campaign when he died of dysentery at Bois de Vincennes. Henry V was succeeded by his infant son, Henry VI.

- In 1429 during the siege of Orleans, the bravery and heavenly visions of Joan of Arc restored the Dauphin as Charles VII of France. In June 1429, the French won at the Battle of Patay after surrounding English archers with the cavalry.

- In December 1431, Henry VI was crowned king of France in the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral. However, this symbolic ritual was without real substance. Despite the aggressive and surprise attacks of the English forces led by John Talbot, English-held Paris and Rouen were soon recaptured by the French.

- The English-Burgundian alliance collapsed when Philip the Good of Burgundy joined Charles VII under the Treaty of Arras in 1435.

- In addition to Dieppe and Paris, the French also recaptured Harfleur by 1440. Despite the marriage of Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou (Charles VII’s niece) in 1445, Charles retook parts of Normandy in 1449. The French recaptured Formigny in 1450, Bordeaux in 1451, Gascony in 1452, and Castillon in 1453. At this time, the English were left with Calais.

- Through marriage alliances and military strategy of conquest, the French crown united the regions of Burgundy, Brittany and Provence. Meanwhile, England was on the verge of bankruptcy, civil war and a weakening king. Henry VI suffered insanity. In 1471, he was killed in the Tower of London.

Impact of the Hundred Years’ War

- The Hundred Years’ War had both short and long-lasting consequences. The series of conflicts killed soldiers, civilians and nobles. In France, the death of nobles destabilised the kingdom. In contrary to England, the war created more nobles that the crown could tax to fund wars.

- The end of the war stripped English-held territories except for Calais. Moreover, political instability also decreased trade, particularly of English wool and Gascony wine.

- To fund the wars, both kingdoms imposed heavy taxes, which resulted in social unrest. Amongst the notable civil war conflicts was the War of the Roses in England. At the end of the Hundred Years’ War, England was on the verge of bankruptcy.

- The war also led to the development of weapons such as cannons and longbows. Sieges and chevauchée were among the common military strategies used.

- The war saw the emergence of Henry V of England, Edward the Black Prince and Joan of Arc as national heroes.

- In England, the war resulted in the development of a stronger Parliament. In contrary to France, the power of the Estates-General weakened.