Kingdom of Kongo Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Kingdom of Kongo to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Formation and History

- Trade and Government

- Christianity

- Decline of the Kingdom of Kongo

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Kingdom of Kongo!

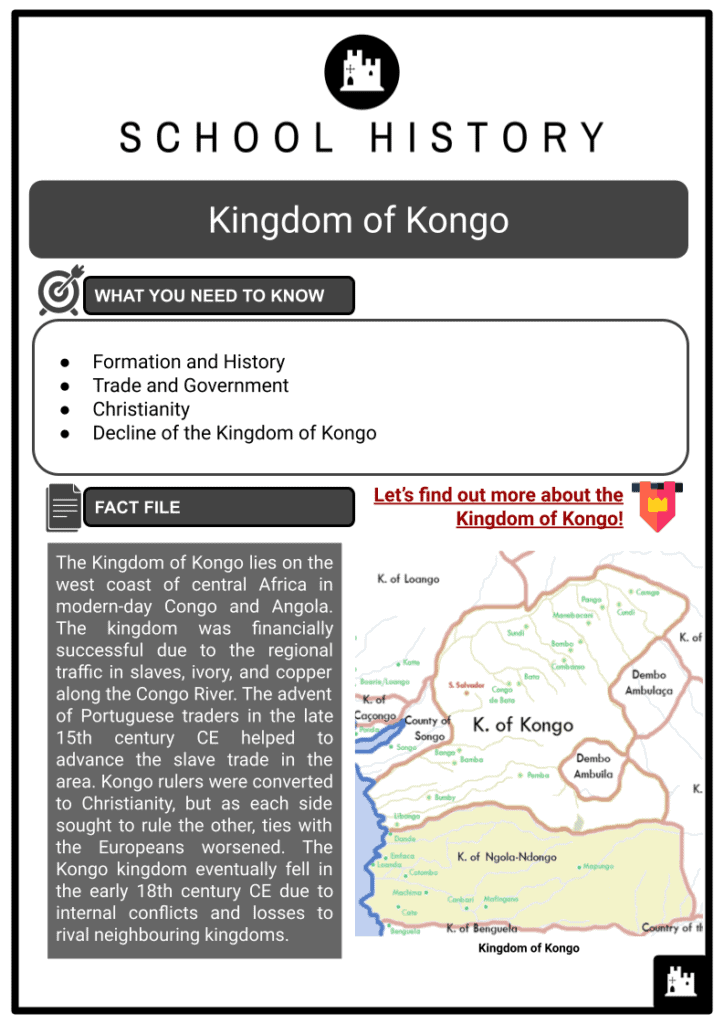

The Kingdom of Kongo lies on the west coast of central Africa in modern-day Congo and Angola. The kingdom was financially successful due to the regional traffic in slaves, ivory, and copper along the Congo River. The advent of Portuguese traders in the late 15th century CE helped to advance the slave trade in the area. Kongo rulers were converted to Christianity, but as each side sought to rule the other, ties with the Europeans worsened. The Kingdom of Kongo eventually fell in the early 18th century CE due to internal conflicts and losses to rival neighbouring kingdoms.

FORMATION AND HISTORY

- The kingdom, which was formed in the late 14th century CE as a result of the union of several regional principalities that had existed since the latter half of the first millennium CE, was situated on the western coast of central Africa, south of the Congo River (previously known as the Zaire River). A rich and well-watered plateau right below the western end of the Congo River was home to Mbanza Kongo, the capital of Kongo, which was ruled by Bantu-speaking people.

- Lack of early written materials and the problematic reality that nearly all later narratives were authored by Europeans make it difficult to understand the early history of the Kingdom of Kongo. This implies that since European accounts were written from the perspective of conquerors and outsiders, it is important to be sceptical of them. Another problem is that local chroniclers—those who wrote from an insider's perspective—made conclusions based on how clans were organised in more recent history, such the Congolese historian Petelo Boka.

- Nonetheless, it is widely accepted that the formation of the Kingdom of Kongo resulted from the both voluntary and unwillful integration of neighbouring states around a single core state.

- Early territorial expansion of the Kongo Kingdom was mostly accomplished by voluntary agreements with smaller neighbouring powers.

- Some historians prefer to refer to states that resemble the Kingdom of Kongo as "commonwealths" rather than "kingdoms" since they were founded in part on collaboration, marital connections, and mutual understanding as opposed to conquest. Conquest was a bigger factor in the Kingdom's later territorial expansion.

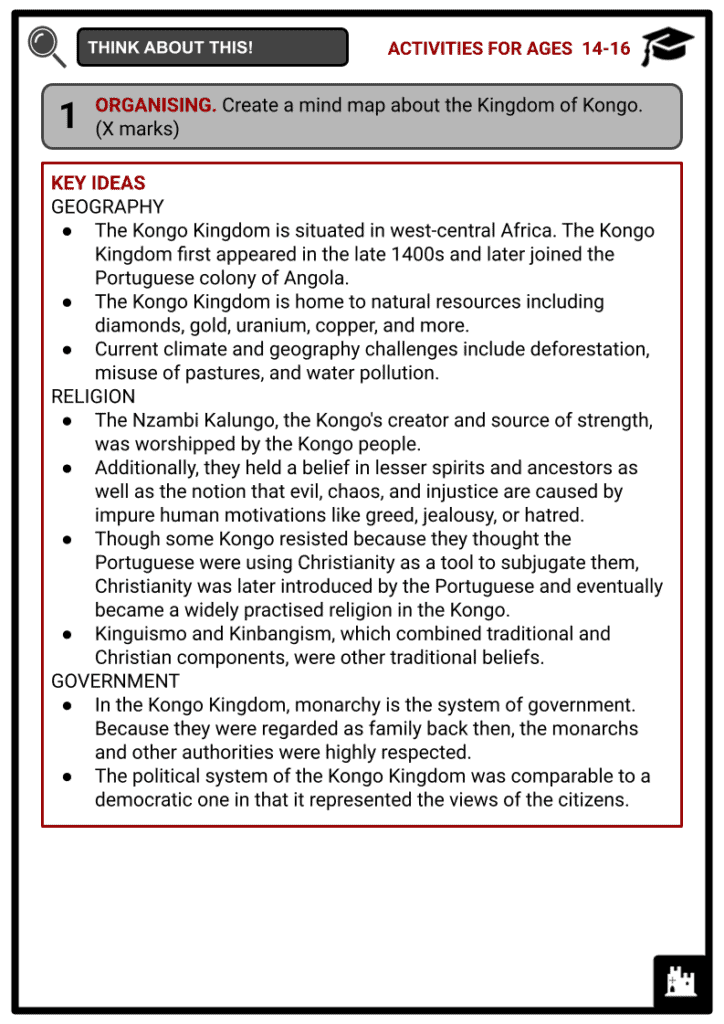

- When the kingdom was at its peak, in the 15th and 16th centuries CE, it controlled about 150 miles of the coast, extending from the Congo River in the north to a point just south of the Cuanza River in the south, and about 250 miles of central African interior, reaching the Kwango River.

TRADE AND GOVERNMENT

- With well over 2 million residents at its height, the kingdom of Kongo flourished owing to commerce in slaves, cow skins, salt, copper, and ivory. The latter trade, which included rotating marketplaces that appeared in cities on set days of the week and sold slaves sourced from the upper reaches of the Congo River, was particularly lucrative and well-regulated. The kingdom not only imported things but also made its own through specialised groups of craftspeople including weavers (who created the famed raffia textiles of Kongo), potters, and metalworkers.

Nzimbu Shells - The established employment of spiral nzimbu shells, a shell currency that originated on the offshore island of Luanda, about 150 miles distant, as a medium of payments amongst the people of the forest and grasslands of west-central Africa, is a sign of the extent of commerce between these groups.

- The shells were first intended to store riches and as a benchmark for determining the worth of other items, but they eventually started to be used like coins to purchase products and labour.

- Rival equatorial African kingdoms included Loango and Tio, both to the north of Kongo, and the loose confederation of tribes of Ndongo to the south, which did not have exclusive trading rights in the area (modern Angola).

- The Kongo kingdom was highly centralised, with a single monarch known as the nkani, selecting regional governors across his territory. These governors in turn elected local leaders and procured tribute from local chiefs, including ivory, millet, palm wine, and leopard and lion skins, which they then sent to the monarch at Mbanza Kongo.

- At grand yearly festivities that included vast quantities of beer drinking and feasting, tributes were paid. Chiefs and officials earned the king's favour, military protection, and certain tangible benefits like culinary delicacies and clothes in exchange for their contributions. The paying of tribute also had a religious component because it was seen as a method to keep both royal and divine favour.

- Kongo kings could be identified by their official regalia, which comprised of a headpiece, throne, stool, drum, and ivory and copper jewelry. The monarch had a regular army of slaves under his command that, by the late 16th century CE, had between 16,000 and 20,000 soldiers. The king was revered as a direct connection to the spiritual dimension and as a protector of the people from natural disasters like sickness and hunger.

- The king had the title "nzambi mpungu," which means "superior spirit" or "supreme creator," however only his office was considered as sacred. King weddings to famous shrine guardians like the mani kabunga, who had looked after the shrine bearing that name since long before the Kingdom of Kongo was founded, served to further this belief.

- A council of around a dozen elders, made up of high-ranking members of the aristocracy (the mwisikongo), which predominated Kongo society, provided the monarch with more temporal advice.

- The aristocrats belonged to a variety of historic family lineages, and most of their income came from trade since the tsetse fly prevented extensive cow breeding in the area and also because owning property was irrelevant due to the small population.

- The tax officer and his staff, the chief of justice, the chief of police, and the official in command of the messenger service were important roles in the centralised administration.

- The free or babuta (farmers and craftsmen) and the unfree or babika comprised the rest of society (slaves who were war captives or those unable to pay their debts).

CHRISTIANITY

- The Portuguese colonised the offshore islands of Sao Tome and Principe in 1470, which led to a boom in Kongo's slave markets. Clothing made of cotton, silk, glazed porcelain, glass mirrors, knives, and beads made of glass were given to the Kongolese in exchange. Only the privileged he favoured had access to these goods because the king tightly regulated their usage.

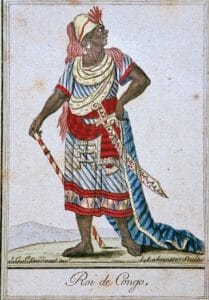

- Following the efforts of Christian missionaries who first arrived in the area in 1491 CE, some Kongo kings converted to Christianity, with King Afonso I being the first.

- The unusual but sparkling rites of the new religion and its apparent connection with prosperous European traders raised the king's status in the eyes of his followers.

- Churches were established, the capital was renamed Sao Salvador, Catholicism was made the official religion of the royal household, and Affonso even succeeded in getting the Pope to approve the appointment of a Kongo bishop.

King Afonso I - The spread of Christianity in the area was greatly aided in the second half of the 17th century CE when Italian Capuchin missionaries began to focus on Kongo.

- The kingdom's art would be permanently altered by the religion, which incorporated elements like the cross and proportional rules from Europe while fusing them with the locals' love of stylisation and geometric decoration to create unique statues, pottery, masks, and relief carvings in everything from copper to ivory as well as woven fabrics.

- In addition to bringing religion, the Portuguese also introduced crops from the Americas, such as maize, cassava, and tobacco, as well as technical skills (masonry, carpentry, and stock-breeding), as part of a larger strategy to westernise Kongo and turn it into a trusted trading partner and a base from which to conquer large portions of central Africa. In the end, however, and similarly to other parts of the continent where the Portuguese were active, the Europeans' greed and ineffective political and religious intervention only served to bring about both their own downfall and that of the native ruler.

- The Portuguese, who were stationed on the island of Sao Tome, started to overthrow the Kongo king and undertake their own attacks to capture slaves from interior Africa, or they simply abducted the Kongolese themselves, which strained relations. Now, there was a large need for slave labour to work the sugarcane fields in Brazil and Sao Tome.

- Additionally, the Portuguese aspired to rule the kingdom's copper mines, enforce their own set of laws, and convert the entire community- not just the ruling class—to Christianity.

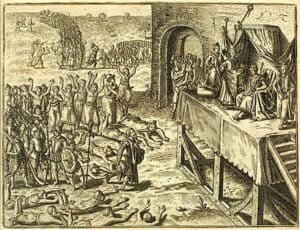

The Portuguese and the Kongo King - The Kongo kings saw the need of getting rid of the Portuguese from their trading relations and realised that by constructing their own fleet, they could convey products to the eager European market themselves.

- The two sides got into a fight about this and were suspicious of one another's motives.

- The Kongo kings came to understand that their traditional position as the political, religious, and economic leaders of the kingdom was being threatened by the unhindered smuggling of slaves and the spread of Christianity, even though the local form of that religion incorporated and coexisted with ancient indigenous beliefs.

DECLINE OF THE KINGDOM OF KONGO

- The decline of the kingdom began in the middle of the 16th century CE when the Portuguese relocated their interests farther south to the region of Ndongo because they were turned off by the interference of Kongo's regulations on trade. In 1556 CE, the latter kingdom had already routed the Kongo army.

- The Kongo kings also experienced internal conflict as a result of rising public discontent over the ever-rising taxes levied against them by an aristocracy eager to acquire expensive foreign goods. The king found it more and more difficult to keep the loyalty of the regional governors since they were enticed to engage directly with the growing number of European traders in the area once the Dutch colonists arrived in the early 17th century CE.

- Around 1568 CE, a mysterious band of warriors known as the Jaga attacked Kongo from the south (or east), and the angry and overburdened people of Kongo rose in favour of them, causing an even larger crisis to arise from beyond the kingdom. Even though the Kongo royal family was able to flee to an outlying island and subsequently mount a partial retaliation after receiving backing from the Portuguese, civil warfare amongst competing heir apparent continued to destroy the kingdom.

- The Kongo was severely defeated by their southern neighbours in the Battle of Mbwila in 1665 CE. The Kongo kings were never able to bounce back from the defeat. Even Sao Salvador was sacked and left in 1678 CE as civil conflicts continued to rage there. Even though the title "King of Kongo" was still in use by 1710 CE, the Kingdom of Kongo had all but ceased to exist as a separate nation. The various trading associations that built alliance networks and trading communities rather than nations took control of the whole region. At some point in the early 20th century CE, the Kongo area was included into the Portuguese province of Angola.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Kongo

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/39/Monetaria_moneta_01.JPG/220px-Monetaria_moneta_01.JPG

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afonso_I_of_Kongo

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Kongo_audience.jpg/440px-Kongo_audience.jpg