Download Richard I of England Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Richard I of England to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Background and early years

- Rebellion and Henry II’s final years

- Succession to the Angevin throne and involvement in the Third Crusade

- Captivity and return to England

- War against Philip II of France

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Richard I of England!

- The third son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Richard I was the second Angevin king of England, ruling from 1189 until his death in 1199. He first displayed his military and political intelligence in controlling the turbulent nobility of his inherited French territories at a young age. During his reign, he became one of the important leaders in the Third Crusade, during which he achieved considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin. After he was freed from captivity in Germany in 1194, the rest of his reign was concentrated on the active defence of his French lands against Philip II of France.

Background and early years

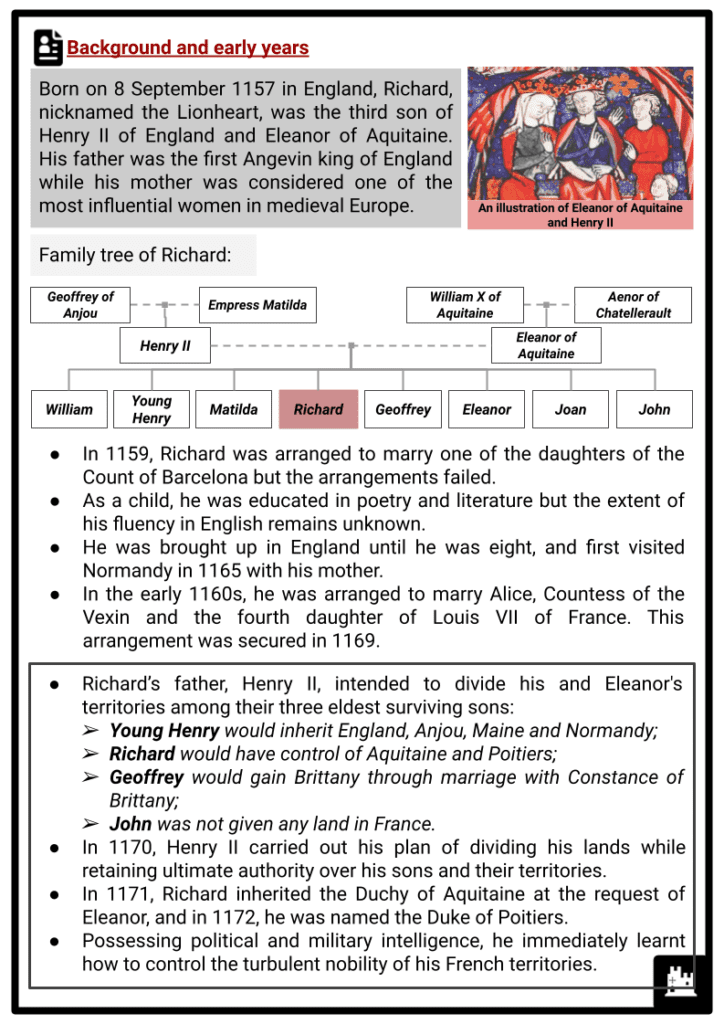

- Born on 8 September 1157 in England, Richard, nicknamed the Lionheart, was the third son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. His father was the first Angevin king of England while his mother was considered one of the most influential women in medieval Europe.

- In 1159, Richard was arranged to marry one of the daughters of the Count of Barcelona but the arrangements failed.

- As a child, he was educated in poetry and literature but the extent of his fluency in English remains unknown.

- He was brought up in England until he was eight, and first visited Normandy in 1165 with his mother.

- In the early 1160s, he was arranged to marry Alice, Countess of the Vexin and the fourth daughter of Louis VII of France. This arrangement was secured in 1169.

- Richard’s father, Henry II, intended to divide his and Eleanor's territories among their three eldest surviving sons:

- Young Henry would inherit England, Anjou, Maine and Normandy;

- Richard would have control of Aquitaine and Poitiers;

- Geoffrey would gain Brittany through marriage with Constance of Brittany;

- John was not given any land in France.

- In 1170, Henry II carried out his plan of dividing his lands while retaining ultimate authority over his sons and their territories.

- In 1171, Richard inherited the Duchy of Aquitaine at the request of Eleanor, and in 1172, he was named the Duke of Poitiers.

- Possessing political and military intelligence, he immediately learnt how to control the turbulent nobility of his French territories.

Rebellion and Henry II’s final years

- In 1173-74, influenced by their mother Eleanor, Richard and his two brothers led the Great Rebellion against their father, after Henry II agreed to grant John three castles in France.

- As a result of Henry II’s bequeathing of Chinon in Touraine, Mirebeau, and Loudon in Poitou to John, Young Henry, Richard and Geoffrey were outraged.

- Young Henry even demanded his father grant him the effective government of a part of his inheritance, which was rejected by the English king.

- At this, Young Henry was urged to rebel by many nobles who saw potential profit and gain in a power transition. Eleanor joined his cause, along with many others who resented Henry II and his policies.

- Despite the several important alliances formed against the English king, the Great Rebellion of 1173-74 was subdued by Henry II.

- Richard went back to England, knelt before his father and asked for forgiveness.

- Upon reconciliation, he was granted the County of Poitou and half of the income of Aquitaine.

- Eleanor, who was captured during the rebellion, remained Henry II's prisoner, perhaps as an insurance for Richard’s good behaviour.

- In 1175, Richard was sent to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him in the rebellion. He successfully forced the rebels into submission.

- He then focused on putting down continuous internal revolts in Aquitaine through punitive campaigns that generated more hostility.

- Between 1180 and 1183, Richard again challenged his father as a result of his refusal to pay homage to Young Henry.

- Young Henry and Geoffrey then attempted to invade Aquitaine to subdue Richard, but the war abruptly ended with Young Henry’s death.

- This resulted in changes to Henry II’s succession plans.

- By 1183, Richard was now named the heir to the English throne.

- Henry II asked Richard to give up Aquitaine for his brother John.

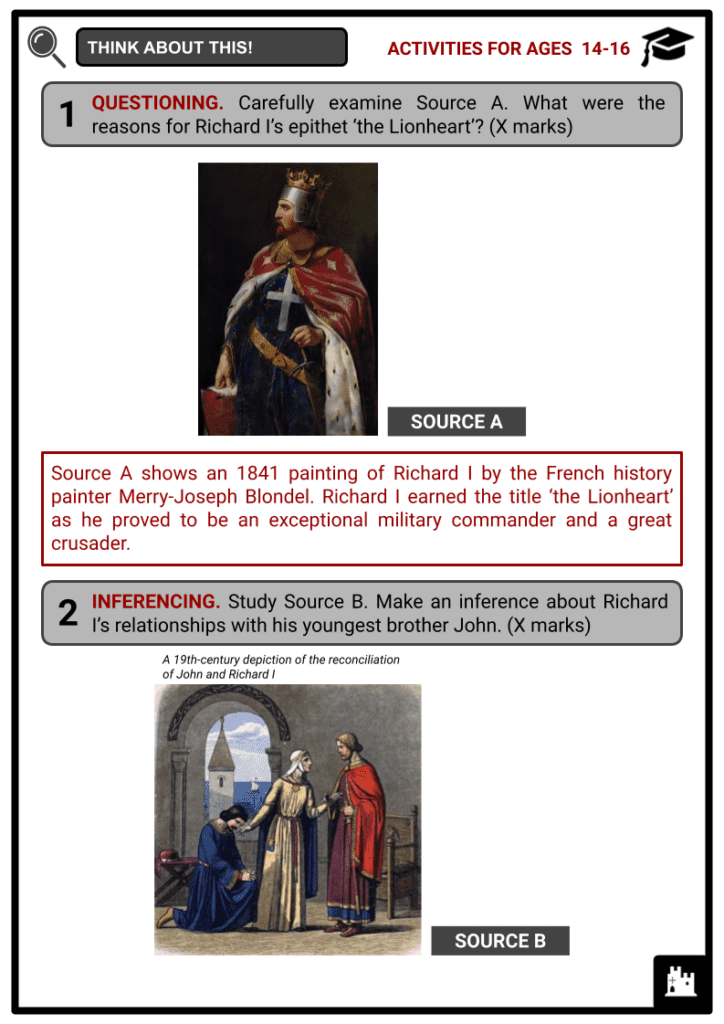

- However, due to Richard’s deep attachment to the duchy, he initially refused but was forced to reconcile with his father thanks to Eleanor’s intervention.

- Despite his submissions, tensions between him and Henry II continued until another scheme against his father was pursued by the alliance of Richard and Philip II of France in 1189.

- Richard attempted to take the English throne by force and Henry II, with John’s consent, agreed to name Richard his heir apparent.

- The English king died two days later.

Succession to the Angevin throne and involvement in the Third Crusade

- Richard I succeeded as the second Angevin king of England, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou in 1189. His coronation took place in Westminster Abbey.

- Tradition dictated that all Jews and women were banned from the investiture.

- During his coronation, some Jewish leaders arrived to present gifts for the new king.

- In response, the king’s courtiers stripped, flogged and flung the Jews out of court.

- Rumours also spread that Richard I ordered all Jews to be killed. This led to pogroms, or mob attacks, by Christians on Jewish homes and property from 1189 until 1190.

- In response to these riots, Richard I ordered the execution of those responsible for the most atrocious murders and persecutions of Jews. He also distributed a royal writ demanding that the Jews be left in peace.

- Despite the king’s order, violence against Jews spread in England, which resulted in around 150 deaths during the massacre of Jews in March 1190 at York Castle.

- Antisemitism, or hatred and discrimination against Jews, grew in Europe during the 12th century because many accused them of killing Jesus Christ out of jealousy over their economic success.

- In England, only about 0.25 per cent of the population were Jews but they provided 8 per cent of the royal treasury’s income.

- The massacres of Jews in London and York coincided with the preparation of the crusaders for the Third Crusade.

- Richard I was one of the leaders of the crusader army, and in order to buy arms for the Crusade, he spent most of his father’s treasury, raised taxes and sold the right to hold official positions, lands and other privileges.

Why did Richard I join the Third Crusade?

- Richard I was religious and strongly believed in his duty as a Christian.

- He thought that the Crusade was his chance to gain honour and glory.

- His desire to recapture Jerusalem was driven by his great-grandfather who had been king of the Holy Land.

- He swore an oath to renounce his past wickedness in order to show himself worthy to take the cross.

- He and Philip II of France agreed to go on Crusade, since each feared that during his absence the other might take over his territories.

The Third Crusade

- With an impressive fleet and an army, Richard I left for the Holy Land and travelled via Sicily in 1190.

- He took Messina by storm and established his base there. He stayed there until the Treaty of Messina was signed in March 1191. Richard I and Philip II remained in Sicily for a while, but this led to increasing tensions between them and their men.

- In May 1191, Richard I invaded Cyprus and married Berengaria of Navarre before leaving for Acre.

- In June 1191, Richard I’s forces joined in attacking the walls of Acre. By July, Saladin’s army was defeated. However, fierce disputes among the French, German and English contingents broke out regarding who should be the king of Jerusalem. Richard I preferred Guy de Lusignan, whilst Philip II and the Germans supported Conrad de Montferrat.

- Following the fall of Acre, Philip II abandoned Richard I and the Crusade out of fear of France being attacked without him. Once Philip II returned to France, Richard I negotiated with Saladin but the arrangements were not successful.

- In response to Saladin’s refusal, Richard I gathered about 2,700 Muslim prisoners and executed them near Saladin’s camp on 20 August. After five days, the crusaders left Acre and marched near the sea to Jaffa. While on their way to Jerusalem, Richard I’s army was protected by a fleet and infantry. Despite constant attacks from Saladin, Richard’s army was able to defend itself. In September 1191, about 30,000 of Saladin’s army attacked the crusaders in Arsuf. Richard I led his knights in defeating the Muslim rivals, before finally marching to Jaffa.

- Following Richard I’s victories at Acre and Arsuf, his army attempted to enter Jerusalem twice. He followed other crusader leaders to Jerusalem but terrible weather destroyed valuable supplies such as food, clothes and weapons. As a result, crusaders diverted to Ascalon.

- When most crusaders had retreated to Ascalon, Saladin attempted to retake Jaffa. While the leaders at Jaffa were about to surrender, Richard I attacked and successfully defended the city. Saladin’s force began a long, weary march back to Jerusalem. However, Richard I failed to attack Jerusalem.

- In September 1192, Richard I made a truce for three years with Saladin, known as the Treaty of Jaffa, which allowed the Crusaders to hold Acre and a thin coastal strip and granted Christian pilgrims free access to the holy places.

Captivity and return to England

- While Richard I was engaged in the Third Crusade, royal authority in England was represented by a Council of Regency in conjunction with the Chief Justiciar. Following the end of the Third Crusade and amidst the ongoing French hostility, Richard I left for England in October 1192. He sailed in disguise but was captured near Vienna by Leopold of Austria.

- Richard I was imprisoned in a castle on the Danube and later handed over to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI.

- The Holy Roman Emperor demanded that 150,000 marks be delivered to him in exchange for the release of Richard I.

- To raise this ransom, England was again subjected to heavy taxation.

How was the ransom raised?

- All laymen and the English Church were taxed for a quarter of the value of their property.

- A feudal aid was raised from the king’s knights amounting to £1 per knight’s fee.

- The gold and silver plates and treasures of the churches were confiscated.

- Money was raised from the scutage (payment made by a knight to commute the military service) and the carucage (land tax based on the size of the taxpayer’s estate).

- The Jewish community was forced to contribute 5,000 marks.

- In February 1194, Richard I was released from imprisonment in Germany and returned at once to England. He was crowned for the second time in April, with the intention to strengthen his kingship that was thought to have been compromised by his captivity. Within a month, he departed for Normandy, never to return.

War against Philip II of France

- During Richard I’s absence in his realms, his brother John revolted with the aid of Philip II. The French king conquered some parts of Normandy. The reconquest of Normandy became Richard I’s aim upon his return from captivity. The fall of the Gisors Castle in the Vexin to the French led the English king to search for a fresh site that could act as his base. He wanted to build a new castle to defend the Duchy of Normandy.

- Richard I took the manor of Andeli by force and commenced the construction of a defence castle later known as the Château Gaillard.

- By 1198, he had worked hard and spent an enormous amount of money to secure alliances with European rulers.

- He organised an alliance with several French counts against Philip II. Meanwhile, Philip II found an ally in Richard I’s nephew, Arthur of Brittany, and teamed up with the barons in Aquitaine to rebel against Richard I.

- Both kings continued to attack the other’s territory, causing great distress to the local population.

- In 1198, Philip II launched an extensive attack on the Vexin but was not completely successful as Richard I’s allies fought the French king.

- At the Battle of Gisors, Richard I advanced through the French territory and captured numerous castles.

- Richard I had the upper hand when finally a truce was agreed in February 1199.

- Under the terms of the truce, Philip II was forced to renounce almost all territorial gains and castles he had won, except Gisors in the Vexin. In essence, the French king appeared to have lost the war.

- Philip II once again stirred up rebellion against Richard I among the barons in Aquitaine.

- In March 1199, Richard I travelled south to punish the rebel barons and besieged the tiny, virtually unarmed castle of Châlus-Chabrol.

- However, a crossbow bolt, believed to have been shot by a boy, caught him between the neck and shoulder.

- Whilst Richard I’s injury was not serious, it caused an infection which led to the English king’s death on 6 April 1199.

- Richard I’s heart was buried at Rouen in Normandy, his entrails in Châlus, and the rest of his body at the feet of his father Henry II at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou.