Saladin Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Saladin to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Unifying the Muslims

- Capturing Jerusalem

- The Third Crusade

- Death and Legacy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Saladin!

Saladin was the Muslim Sultan of Egypt and Syria who stunned the western world by defeating a Christian Crusader army in the Battle of Hattin and then capturing Jerusalem in 1187. In order to unify the Muslim Near East from Egypt to Arabia, Saladin used a potent combination of military conquest, diplomacy and the threat of holy war. Saladin was honoured by both Christian and Muslim writers due to his prowess in battle and politics as well as his personal virtues of generosity and bravery.

UNIFYING THE MUSLIMS

- Saladin, whose full name was al-Malik al-Nasir Salah al-Dunya wa'l-Din Abu'l Muzaffar Yusuf Ibn Ayyub Ibn Shadi al-Kurdi, was born in 1137 in the fortress of Takrit, north of Baghdad, to Ayub, a displaced Kurdish mercenary. Saladin would advance in the military, where he had a reputation for being a talented polo player and a competent rider. He went on the same war as his uncle Shirkuh, who in 1169 conquered Egypt. Then Saladin replaced Nur ad-Din (or Nur al-Din), the independent ruler of Aleppo and Edessa, as Egypt’s ruler. When Nur ad-Din passed away in May 1174, his alliance of Muslim kingdoms disintegrated as his heirs fought for dominance. Saladin claimed to be the rightful heir and seized control of Egypt.

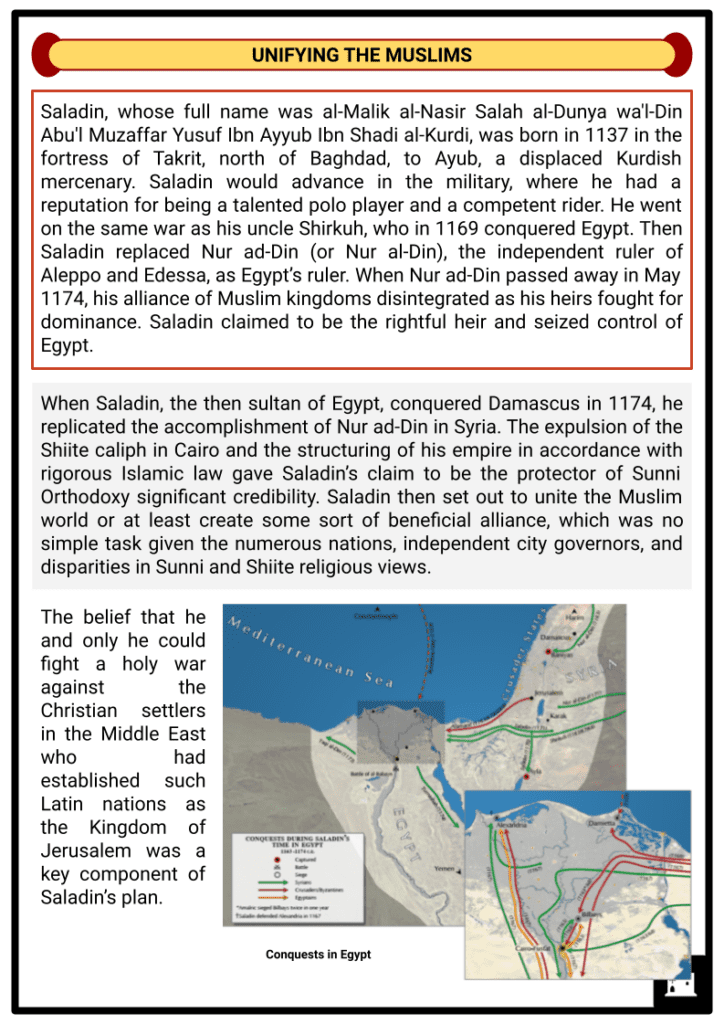

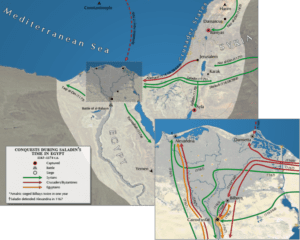

Conquests in Egypt - When Saladin, the then sultan of Egypt, conquered Damascus in 1174, he replicated the accomplishment of Nur ad-Din in Syria. The expulsion of the Shiite caliph in Cairo and the structuring of his empire in accordance with rigorous Islamic law gave Saladin’s claim to be the protector of Sunni Orthodoxy significant credibility. Saladin then set out to unite the Muslim world or at least create some sort of beneficial alliance, which was no simple task given the numerous nations, independent city governors, and disparities in Sunni and Shiite religious views.

- The belief that he and only he could fight a holy war against the Christian settlers in the Middle East who had established such Latin nations as the Kingdom of Jerusalem was a key component of Saladin’s plan.

- But first, the military chief had no qualms about declaring war on his Muslim opponents. He defeated an army from a rival state at Aleppo in 1175, for instance, at Hama.

- When the caliph of Baghdad, the leader of Sunni Islam, legally recognised Saladin as the ruler of Egypt, Syria and Yemen, it solidified his position as the most powerful Muslim leader.

- Unfortunately, Aleppo remained independent and posed a significant diplomatic challenge for Saladin since it was commanded by the son of Nur ad-Din.

- More personal dangers also existed since the formidable Shiite sect known as the Assassins twice attempted to kill the Sultan of Egypt, but he managed to survive both times. In Syria’s Masyaf, the castle of the Assassins was attacked by Saladin, who then pillaged the surrounding region.

- In the meantime, the diplomatic option was also used, particularly in the marriage of Nur ad-Din’s Ismat, who was also the descendant of the late Damascan ruler Unur. Saladin thus conveniently allied himself with two governing dynasties at once. Saladin’s intention to completely purge the Middle East of westerners was demonstrated by victories in 1179 at Marj Ayyun and the capture of a fairly large fortress on the Jordan River despite setbacks along the way, including the defeat to the Franks, as the western settlers were known, at Mont Gisard in 1177.

- Saladin’s developing reputation for justice and kindness, as well as his own carefully created image as the protector of Islam against competing religions, particularly Christianity, were both beneficial to him. When Saladin conquered Aleppo in May 1183, he further strengthened his position.

- He also did this by wisely assembling a highly important Egyptian naval fleet. By 1185, Saladin had taken control of Mosul, and he formed a pact with the Byzantine Empire to cooperate against their shared adversary, the Seljuks. Now that his own borders were protected, he could travel to the Latin American countries with confidence. The moment for Saladin to attack was now since the Franks were preoccupied with succession disputes and the question of who should lead the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

- A force led by Saladin’s son, al-Afdal, proceeded on Acre after the Franks’ castle at Kerak was attacked in April 1187, while Saladin himself assembled a massive army made up of soldiers from Egypt, Syria, Aleppo and Jazira (northern Iraq). As Saladin’s siege of Tiberias continued, the Franks assembled their troops in response, and the two armies met at Hattin.

CAPTURING JERUSALEM

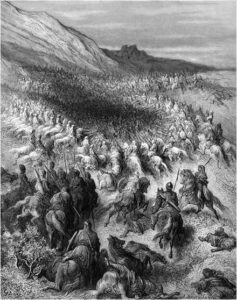

- Saladin’s mounted archers constantly attacked and retreated, harassing the advancing Franks as the battle of Hattin began in earnest on 3 July 1187. The arrows pierced them, turning their lions into hedgehogs, as one Muslim historian described it. The next day, a more significant engagement took place. At Hattin, Saladin was able to deploy about 20,000 soldiers. Guy of Lusignan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, served as the head of the Franks, who could field some 15,000 soldiers and 1,300 knights.

Battle of Hattin - The Muslim army, which had plenty of supplies due to their camel trains, set fire to the dry grass and bushes to increase the enemy’s thirst while the Franks were outnumbered and severely dehydrated.

- The infantry were in disarray and no longer forming the customary ring of protection for the heavy cavalry when the Franks’ formation broke apart.

- The Muslim defences were breached by a cavalry group under the command of Raymond of Tripoli, but the rest of the army was unable to flee, and Saladin easily defeated the biggest army the Franks had ever amassed.

- Saladin handed a cold sherbert to Guy in a customary act of generosity. Like in other medieval battles, certain nobility, including Guy, were let free upon the payment of a ransom. Others weren’t as lucky. Reynald of Chatillon, the Prince of Antioch, was beheaded by Saladin after the latter had earlier attacked a Muslim caravan and chopped off one of Reynald’s arms with his scimitar. The two military orders’ knights, the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar, were also sentenced to death since they were seen to be excessively dangerous and fanatical (in addition to having little chance of securing any ransom). The remaining captives were bought and sold into slavery.

- Saladin took control of Jerusalem in September 1187, which was now almost completely undefended and held great symbolic value for both sides. Christians in the city once more resisted being massacred in large numbers, and the majority were either ransomed or forced into slaves. Eastern Christians were allowed to stay in the city, despite the fact that mosques were built in the place of all except the Holy Sepulchre’s churches.

- Saladin already held control over a number of significant cities, including Acre, Tiberias, Caesarea, Nazareth and Jaffa.

- Tyre was the only large city in the Middle East that was still under western control.

- Saladin’s heroic character was established with the victory at Hattin, the seizure of the True Cross, the most sacred object to the Franks, and the destruction of Jerusalem’s Holy City.

- The Sultan worked hard to build his reputation, even hiring two official biographers to document his accomplishments.

- The same was true for institutions of higher learning and religion, whose works praised their sponsors’ merits.

- The Sultan was famous for his passion for gardening, poetry and hunting. He was also renowned for his kindness, especially among his relatives who oversaw the regions of his kingdom.

THE THIRD CRUSADE

- Saladin had long considered the idea of waging a holy war against the western Christian forces, and now that he had taken Jerusalem, he would have to do it. The three most powerful monarchs in Europe – Frederick I Barbarossa, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor; Philip II of France; and Richard I, ‘the Lionheart’ of England – responded to Pope Gregory III’s call for a Third Crusade to retake Jerusalem.

- The Crusader army then advanced southeast towards Jerusalem while being harassed by Saladin’s army along the way.

Philip and Richard - On 7 September 1191, a major fight then broke out on the plain of Arsuf.

- Saladin was forced to retreat to the relatively secure haven of the woodland that bordered the plain as the Crusaders won the day, although Muslim losses were not great.

- Saladin’s army had not been seriously harmed by Acre or Arsuf, but the two losses that came so quickly after one another, together with the subsequent fall of Jaffa to Richard I in August 1192, did impair Saladin’s military standing among his contemporaries.

- Guy of Lusignan returned to the campaign route in the meantime. In August 1189, he had set out from Tyre with some 7,000 infantry soldiers, 400 knights and a small Pisan navy to start a siege of Acre, which was ruled by Muslims. It was the start of a protracted and difficult siege, and Saladin’s land army was encircling the Frankish strongholds. Only the ultimate arrival of Philip and Richard’s forces turned the tide in the Crusaders’ favour. On 12 July 1191, the city was completely conquered, along with 70 ships, the majority of Saladin’s navy.

DEATH AND LEGACY

- Saladin passed away shortly after in Damascus on 4 March 1193, preventing him from taking advantage of the Crusaders’ withdrawal. He was just 55 or 56 years old when he passed away, and it was likely the physical toll of years spent in the war. Once their great leader had passed away, the fragile and frequently unstable Muslim alliance swiftly fell apart. Three of Saladin’s sons each gained leadership of Egypt, Damascus and Aleppo, while other relatives and emirs fought over the remaining territories.

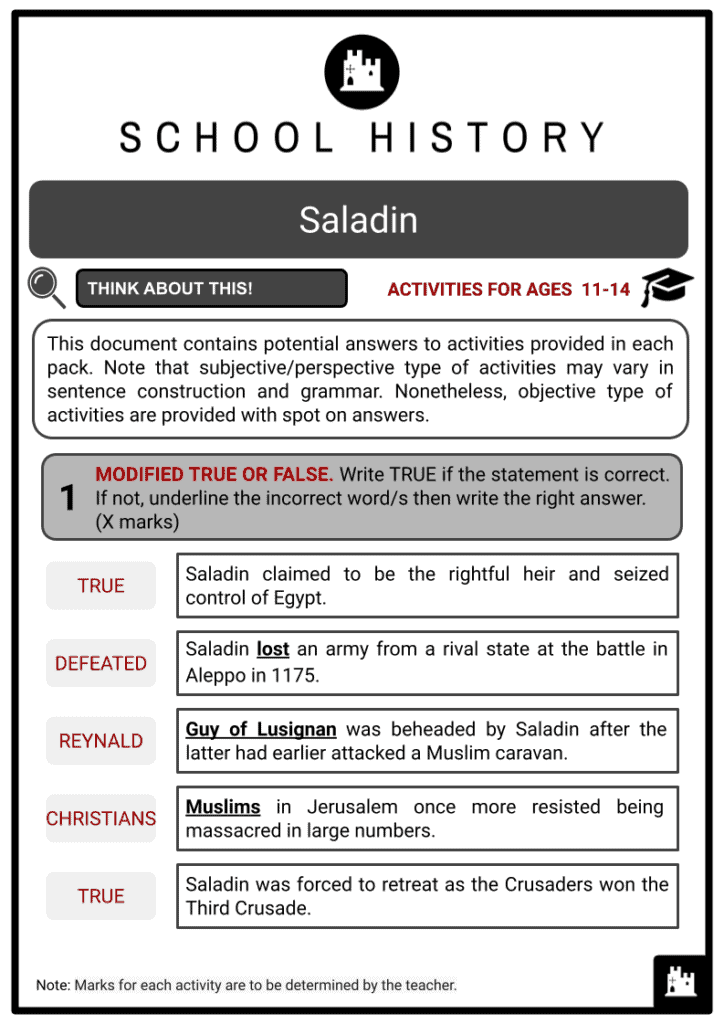

Mausoleum of Saladin - Saladin did leave a lasting legacy since he established the Ayyubid dynasty, which governed Egypt until 1250 and Syria until 1260 before being ousted by the Mamluks in both countries.

- Saladin also left a literary legacy that includes both Christian and Muslim authors.

- It is ironic, in fact, that the Muslim commander ended up being one of the most prominent figures in literature from the 13th century in Europe.

- There has been much written about the Sultan both during his lifetime and subsequently, but the fact that Saladin’s leadership and diplomatic abilities are praised in both modern Muslim and Christian sources would imply that he is deserving of his place among the greatest medieval leaders.

- Saladin is a well-known historical figure who is buried in a tomb outside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria. German Emperor Wilhelm II gave the mausoleum a brand-new marble sarcophagus, but Saladin wasn’t buried in it. Instead, the tomb currently holds two sarcophagi: one made of wood with Saladin’s body inside and one made of marble with no body inside.

Image Sources

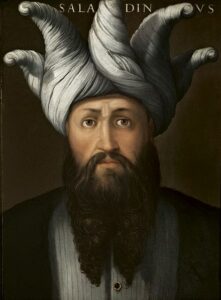

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Cristofano_dell%27altissimo%2C_saladino%2C_ante_1568_-_Serie_Gioviana.jpg/440px-Cristofano_dell%27altissimo%2C_saladino%2C_ante_1568_-_Serie_Gioviana.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Saladin_in_Egypt_Conquest.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Gustave_Doré-_Battle_of_Hattin.jpg/440px-Gustave_Doré-_Battle_of_Hattin.jpg

- https://cdn2.picryl.com/photo/2022/01/04/philippe-auguste-et-richard-iiie-croisade-ecd352-small.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Saladin_mouselum_tomb_Damascus.jpg/500px-Saladin_mouselum_tomb_Damascus.jpg