The Reconquista Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about The Reconquista to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Reconquista

- Medieval Iberia

- Military Orders

- Second Crusade

- Victory

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Reconquista!

Between the 11th and 13th centuries CE, the Iberian Crusades, commonly known as the Reconquista, liberated southern Portuguese and Spanish territories. The final years of the 13th century CE signalled successful military campaigns with the backing of popes and attracting Christian knights from across Europe. On the other hand, only the heavily fortified Granada remained in Muslim hands during this period.

EARLY RECONQUISTA

BEGINNING OF THE RECONQUISTA

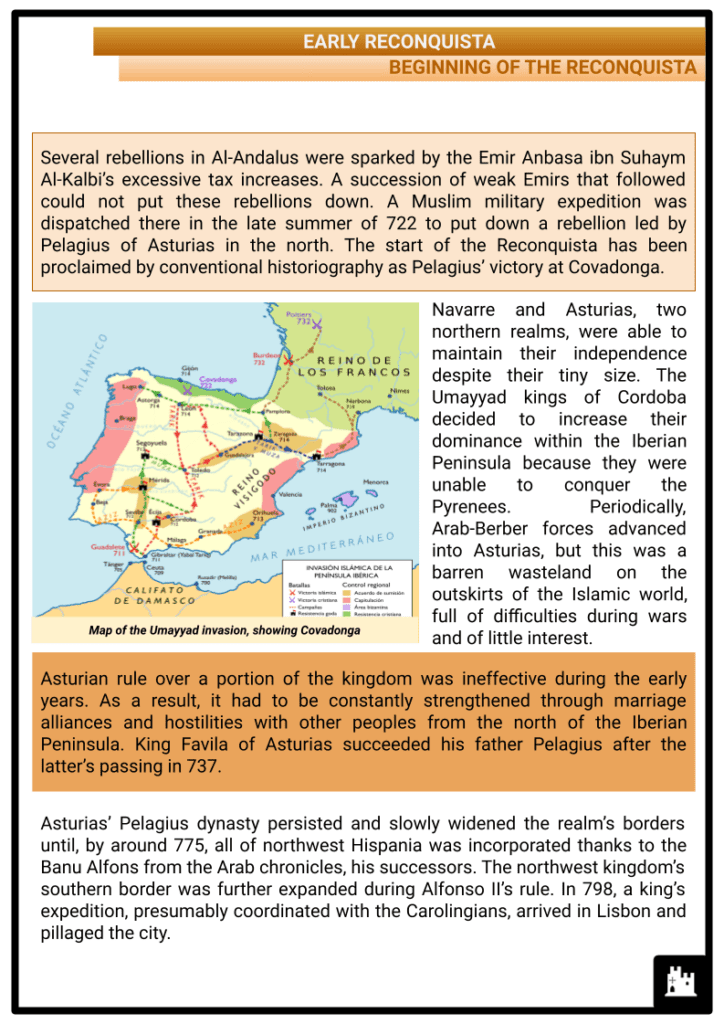

- Several rebellions in Al-Andalus were sparked by the Emir Anbasa ibn Suhaym Al-Kalbi’s excessive tax increases. A succession of weak Emirs that followed could not put these rebellions down. A Muslim military expedition was dispatched there in the late summer of 722 to put down a rebellion led by Pelagius of Asturias in the north. The start of the Reconquista has been proclaimed by conventional historiography as Pelagius’ victory at Covadonga.

- Navarre and Asturias, two northern realms, were able to maintain their independence despite their tiny size. The Umayyad kings of Cordoba decided to increase their dominance within the Iberian Peninsula because they were unable to conquer the Pyrenees. Periodically, Arab-Berber forces advanced into Asturias, but this was a barren wasteland on the outskirts of the Islamic world, full of difficulties during wars and of little interest.

- Asturian rule over a portion of the kingdom was ineffective during the early years. As a result, it had to be constantly strengthened through marriage alliances and hostilities with other peoples from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. King Favila of Asturias succeeded his father Pelagius after the latter’s passing in 737.

- Asturias’ Pelagius dynasty persisted and slowly widened the realm’s borders until, by around 775, all of northwest Hispania was incorporated thanks to the Banu Alfons from the Arab chronicles, his successors. The northwest kingdom’s southern border was further expanded during Alfonso II’s rule. In 798, a king’s expedition, presumably coordinated with the Carolingians, arrived in Lisbon and pillaged the city.

Map of the Umayyad invasion, showing Covadonga - When Charlemagne and the Pope recognised Alfonso II as the king of Asturias, the Asturian kingdom was securely established. During his rule, Santiago de Compostela in Galicia was claimed to be the location of St James the Great’s remains. Many decades later, European pilgrims connected the secluded Asturias with the Carolingian kingdoms and beyond.

FRANKISH INVASIONS

- Following the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic kingdom’s Iberian core, the Muslims crossed the Pyrenees. They gradually seized control of Septimania, beginning in 719 with the invasion of Narbonne and continuing until 725 with the conquest of Carcassonne and Nîmes. They attempted to take Aquitaine from the stronghold of Narbonne but were severely defeated at the Battle of Toulouse.

- The Carolingian monarch Pepin the Short overran Aquitaine in a brutal eight-year war after driving the Muslims from Narbonne in 759 and forcing their armies back over the Pyrenees. Following in his father’s footsteps, Charlemagne divided Aquitaine into counties, allied himself with the Church, appointed counts of Frankish or Burgundian descent, such as his devoted William of Gellone, and used Toulouse as his headquarters for campaigns against Al-Andalus.

- To control the Aquitanians and defend the southern boundary of the Carolingian Empire against Muslim incursions, Charlemagne decided to establish a regional subkingdom, the Spanish March, which encompassed a portion of modern-day Catalonia. Under the guidance of Charlemagne’s trustee William of Gellone, his three-year-old son Louis was anointed king of Aquitaine in 781 and was formally in control of the nascent Spanish March.

- In 778, Charlemagne embarked on an expedition after spotting an opportunity. Sulayman al-Arabi paid Charlemagne tribute close to the city of Zaragoza. But Husayn’s leadership caused the city to shut its gates and stand its ground. Charlemagne decided to leave after failing to take the city by force. At the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, on the way home, Basque forces ambushed and wiped out the army’s rearguard.

- Count Wilfred made Barcelona the de facto area’s capital in the late ninth century. It governed the other counties’ policies in a union, which resulted in Barcelona’s independence in 948 under Count Borrel II, who proclaimed that the new French dynasty was neither the rightful ruler of France nor his county. Except for Navarre, these republics were minor and lacked Asturias’ ability to combat the Muslims. Still, their mountainous terrain protected them from conquest, and their borders remained unchanging for two centuries.

MEDIEVAL IBERIA

NORTHERN CHRISTIAN REALMS

In the early eighth century, the Muslim Moors, located in North Africa, had taken control of most of the Iberian Peninsula, which the Visigoths then ruled. The internal wars within the Cordoba Caliphate in 1031 CE substantially aided the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain in their attempt to recapture some of the lost territories by the 11th century. Aragon, Catalonia, Castile, Leon and Navarre were the five Spanish provinces engaged. Portugal had existed as a separate state since the 1140s CE.

KINGDOM OF LEON

-

- The strategically significant city of Leon was repopulated, and Alfonso III of Asturias made it his capital. King Alfonso launched several campaigns to seize control of all the territory north of the Douro River. He divided his lands into large counties and duchies and reinforced the frontiers with several castles.

- As it gained strength, the Caliphate of Cordoba started to assault Leon. King Ordoo united with Navarre to fight Abd-al-Rahman, but they were destroyed in Valdejunquera in 920. For the following 80 years, civil warfare, Moorish assault, internal conspiracies and assassinations, as well as Galicia and Castile’s partial independence, plagued the Kingdom of Leon, delaying the reconquest and weakening the Christian armies.

- Galicia, which was left temporarily independent when the Leonese king withdrew, was not a part of the conquest of Leon. Galicia was rapidly subdued following that. Galicia was a kingdom and fief of Leon during this brief time of independence, which is why it is a part of Spain and not Portugal.

20th-century ceramic depiction of the conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI, at the Plaza de España

KINGDOM OF CASTILE

-

- The most crucial king in the middle of the eleventh century was Ferdinand I of Leon. He overthrew Coimbra and assaulted the Taifa kingdoms, frequently demanding the parias’ contributions. Ferdinand planned to keep pressing for parias until the Taifas were severely undermined both economically and militarily. He also brought many fueros back to the Borders.

- When he passed away in 1064, he divided his realm between his sons as per Navarrese custom. A young nobleman named Rodrigo Daz, later known as El Cid Campeador, accompanied his son Sancho II of Castile when he assaulted his brothers to unify his father’s realm.

- Alfonso VI the Brave repopulated Segovia, Vila and Salamanca while giving the fueros additional authority. In 1085, after establishing the Borders, King Alfonso overthrew Toledo, a significant Taifa state. Toledo, the old Visigoth capital, was a considerable landmark, and Alfonso became well-known across the Christian world due to the conquest. Alfonso VI was, first and foremost, a diplomatic king who sought to understand the rulers of Taifa and used novel prudent techniques to advance his political goals before considering force. Imperator Totius Hispaniae was the title he adopted.

KINGDOM OF NAVARRE

-

- Pamplona and the surrounding area saw the growth of the medieval state during the early years of the Iberian Reconquista. The kingdom was established due to the conflict between the Carolingian Empire and the Umayyad Emirate of Cordoba, which dominated most of the Iberian Peninsula.

- The kingdom briefly escaped Cordoba’s vassalage in the first quarter of the 10th century and grew militarily, but Cordoba soon regained control until the early 11th century. Its area was reduced due to divisions and dynastic shifts, and the kings of France and Aragon ruled briefly during this time.

- Another dynastic conflict over the monarch of Aragon’s authority in the 15th century caused internal strife. It ultimately resulted in the southern region of the kingdom being annexed by Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1512. The Courts of Castile included it in the Crown of Castile in 1515. The remaining northern part of the kingdom was once more joined with France by the personal union in 1589 when King Henry III of Navarre became Henry IV of France. It was included in the Kingdom of France in 1620.

KINGDOM OF ARAGON

-

- The contemporary autonomous community of Aragon in Spain is a descendant of the medieval and early modern country known as the country of Aragon, which was located on the Iberian Peninsula.

- This is not to be confused with the Crown of Aragon. However, some lands were ruled by the King of Aragon but were handled separately from the Kingdom of Aragon, including the Kingdom of Majorca, the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, and other territories that are now part of France, Italy and Greece.

- The Crown of Aragon joined the Spanish monarchy after the dynastic union with Castile, which signified the de facto unification of both kingdoms under a single ruler. The Barcelona family held the throne until its extinction in 1410. After fierce Catalan opposition, the Aragonese elected Ferdinand of Antequera, a prince from Castile, to the vacant Aragonese throne in 1412. To overcome the remaining Catalan resistance, one of Ferdinand’s successors, John II of Aragon, arranged for his heir, Ferdinand, to wed Isabella, Henry IV of Castile’s heir apparent.

- Today’s Spain was formed when the crowns of Aragon and Castile were united following John II’s death in 1479. The Aragonese provinces continued to have separate parliamentary and administrative organisations, such as the Corts, until the Nueva Planta decrees, which Philip V of Spain issued between 1707 and 1715 in the wake of the War of the Spanish Succession.

- A new Nueva Planta decree in 1711 restored some rights in Aragon, such as the Aragonese Civil Rights, but upheld the end of the political independence of the kingdom. The decrees de jure ended the kingdoms of Aragon, Valencia and Mallorca, as well as the Principality of Catalonia, and merged them with Castile to officially form the Spanish empire.

MILITARY ORDERS

KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER AND KNIGHTS TEMPLAR

- The Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar were two military orders of professional warrior monks who would become vital to the defence of the Crusader States in the Middle East. The enticement eventually worked, and both orders would send knights to the Reconquista – the Hospitallers in 1148 CE and the Templars in 1143 CE – despite being later scaled back by Spanish lords. The Iberian Peninsula would also witness the establishment of its regional military orders, beginning in 1158 CE with the Order of Calatrava, whose knights were renowned for donning black armour.

KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER

-

- As ‘Knights of the Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem,’ the Knights Hospitaller was a Catholic military order that dated back to the Middle Ages and was established in 1113 CE. The order’s original mission was to aid and treat Christian pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land. Nevertheless, it quickly developed into a military order with vast holdings in Europe and knights who made a great impact in the Middle Eastern and Iberian Crusades.

KNIGHTS TEMPLAR

-

- The Knights Templar dates back to its recognition from the Pope in 1119 and 1129. It was a Catholic military order from the Middle Ages that used its members’ martial prowess and dedication to monastic life to protect Christian pilgrims and sacred sites throughout the Middle East. The Knights Templar eventually grew to be a very strong organisation, controlling both castles and territory in the Levant and all over Europe.

With the creation of the Order of Santiago, Montjoy in Aragon, Alcantara, and the Order of Evora in Portugal, the 1170s CE proved to be a busy decade for new military organisations. The main benefit of these local orders was that, unlike the Templars and Hospitallers, they were not required to transmit a third of their income to a Middle Eastern headquarters. As the riches in southern Spain attracted seasoned explorers from other parts of Europe, particularly northern France and Norman Sicily, a lot more warriors would soon be on their way to aid the Christian Spanish kings as well.

SECOND CRUSADE

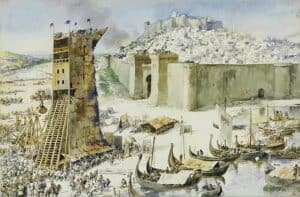

SIEGE OF LISBON

- The Second Crusade, which drew would-be pious soldiers from all around northern Europe, began in early 1147, with its headquarters in the Devon town of Dartmouth. The combined fleet contained a minimum of 164 ships. A priest served each parish onboard each ship, which could accommodate about 50 soldiers.

- The crusaders decided to assist Afonso I of Portugal in freeing Lisbon from the Moors at Oporto. They arrived in the city on 28 June 1147. Raol was among the first to arrive at the coast and was one of only 39 people who spent the first night camping beneath the city walls. The crusaders besieged Lisbon on 1 July as Afonso and his men captured the nearby countryside. As they pounded the city, the crusaders constructed manzanels. A sortie destroyed the siege engines by the Muslims.

Portrait depicting the Siege of Lisbon as part of the Portuguese Reconquista and the Second Crusade - The garrison agreed to surrender on 21 October in exchange for being given free rein to leave. Lisbon’s gates were unlocked four days later. Due to the mutually agreed-upon capitulation, the crusaders received less plunder. While the Germans and Flemings carried on to the Holy Land, many English crusaders chose to stay in Portugal and one became the Bishop of Lisbon. Lisbon became the capital of Portugal, which won papal recognition as an independent kingdom.

The enemy, when they had been despoiled in the city, left the town through three gates continuously from Saturday morning until the following Wednesday. There was such a multitude of people that it seemed as if all of Hispania were mingled in the crowd.

- Jonathan Phillips, The Conquest of Lisbon: De Expugnatione Lyxbonensi

VICTORY

CHRISTIAN VICTORY

- Pope Innocent III, who supported liberating the Iberian Peninsula in 1212 CE, gave the Spanish kings, who had suffered a crushing loss at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195 CE, a much-needed boost. There needed to be more unity among the Christians in Spain as well.

- The Pope excommunicated King Alfonso IX of Leon for his alliance with the Muslims. In an even more unprecedented move, he granted the forgiveness of sins to every Christian who opposed the king. Christians were now engaged in combat with other Christians as a result. Muslim and Christian statelets had a long history of working together in Spain, with trade and economic interests frequently taking precedence over religious differences. There was also no widespread demonisation of Muslims like there was in the Middle East.