Treaty of Brétigny Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Treaty of Brétigny to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years’ War

- Terms and outcomes of the Treaty of Brétigny

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Treaty of Brétigny!

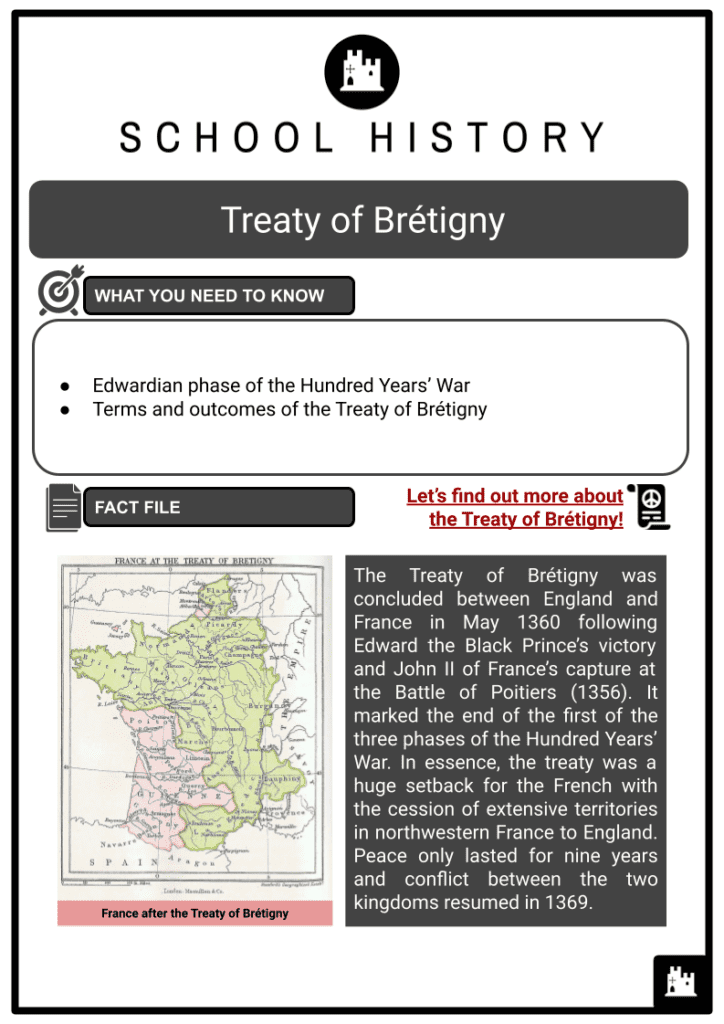

The Treaty of Brétigny was concluded between England and France in May 1360 following Edward the Black Prince’s victory and John II of France’s capture at the Battle of Poitiers (1356). It marked the end of the first of the three phases of the Hundred Years’ War. In essence, the treaty was a huge setback for the French with the cession of extensive territories in northwestern France to England. Peace only lasted for nine years and conflict between the two kingdoms resumed in 1369.

Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years’ War

- The Hundred Years’ War was a series of conflicts from 1337 to 1453. It drew in many allies of the English House of Plantagenet against the French House of Valois over the right to rule the kingdom of France and the issue of sovereignty. The conflict spanned five generations of kings and two rival dynasties over the largest kingdom in Western Europe.

- The French origins of the English royal family had become the root of tensions between the French and English monarchies over the centuries since the Norman conquest of England.

- It was because English monarchs held much land and titles within France, which made them vassals to the kings of France. The French fiefs of the English monarchs were a major source of conflict.

- The size of English land ownership in France varied over the years, sometimes dwarfing that of French ownership.

- France would strip away land, wealth and titles from England where opportunity arose in order to keep the growth of England in check. This especially happened when England was at war with Scotland, an ally of France.

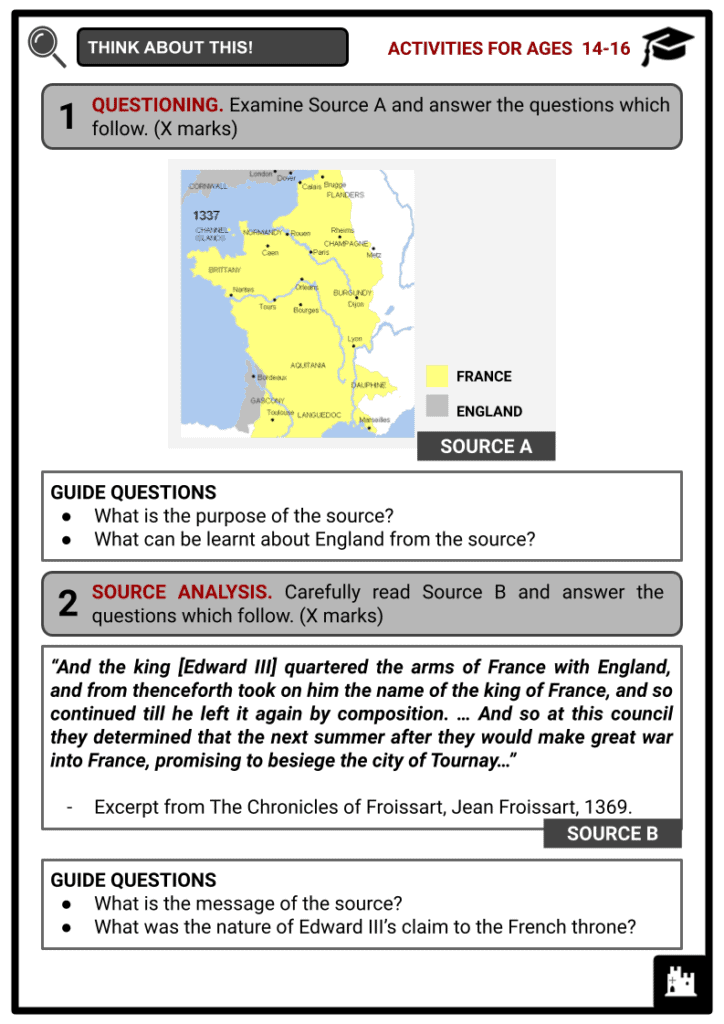

- In 1337, only Gascony in France was held by England. That year, Edward III, king of England from 1327, experienced ongoing conflict with Scotland. Philip VI of France allied with Scottish King David II.

- The English king was aware that he could not fight a war on two fronts. In retaliation, he provided refuge for French fugitive Robert III of Artois.

- This prompted the French king to confiscate Edward III’s French Duchy of Aquitaine on the grounds that the latter was in breach of his obligations as vassal and had sheltered the French fugitive.

- Edward III responded by reasserting his claim to the French throne, marking the beginning of the first of the three phases of the Hundred Years’ War known as the Edwardian War.

- This phase ensued from 1337 to 1360.

Depiction of Edward III of England and Philip VI of France - However, Edward III’s alliances failed to measure up to France’s. He experienced no real victories in the early stages other than a naval victory at the Battle of Sluys in 1340, which secured English control of the Channel.

- Meanwhile, discontent grew back home in England, created by debt and financial pressure from the war. By 1340, Edward III returned to England and purged his administration. However, instability continued.

- New limitations were imposed on English monarchs who were given defined duties and limits. Come July 1346, Edward III staged a major offensive in Normandy with 15,000 men and met up with English forces in Flanders. The 35,000-strong army dominated the Battle of Crécy.

- Having lost the Battle of Crécy and Calais to England, the Estates of France refused to fund Philip VI’s plan to counter-attack and invade England.

- By 1348, the Black Death was sweeping through England and France wiping out over a third of the population.

- The epidemic killed millions, creating labour shortages and impacting wages and inflation.

- Both Philip VI and Edward III concentrated on stabilising their countries and ceased conflict. Military operations in France only resumed on a large-scale in the mid-1350s.

- Philip VI died in 1350 and was succeeded by his son, John II.

- In 1356, Edward III’s eldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, fought and won the Battle of Poitiers. He captured John II and his son Philip.

- England enjoyed a series of victories and held large swathes of France. The French king was in custody and the French government nearing collapse in his absence.

Depiction of the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 - Proposed by England and accepted by France, the Treaty of London in 1359 followed the Black Prince’s resounding victory at Poitiers. In the terms, England was permitted to annex its lands, such as Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Aquitaine, within its ancient limits of Calais and Ponthieu, and was given independence rather than the fiefdom of the Duchy of Brittany. In addition, France would pay a ransom of three million gold coins for John II’s release. The French Estates-General rejected the treaty, stating too much territory was being relinquished.

Terms and outcomes of the Treaty of Brétigny

- Edward III launched a fresh invasion and besieged Rheims. As supplies ran low, he was forced to withdraw to Burgundy. A failed attempt to besiege Paris was made by the English army, after which the English king marched to Chartres and decided to reopen negotiations with France. The resulting truce known as the Treaty of Brétigny was signed between John II of France and Edward III of England in May 1360.

What were the terms of the Treaty of Brétigny?

-

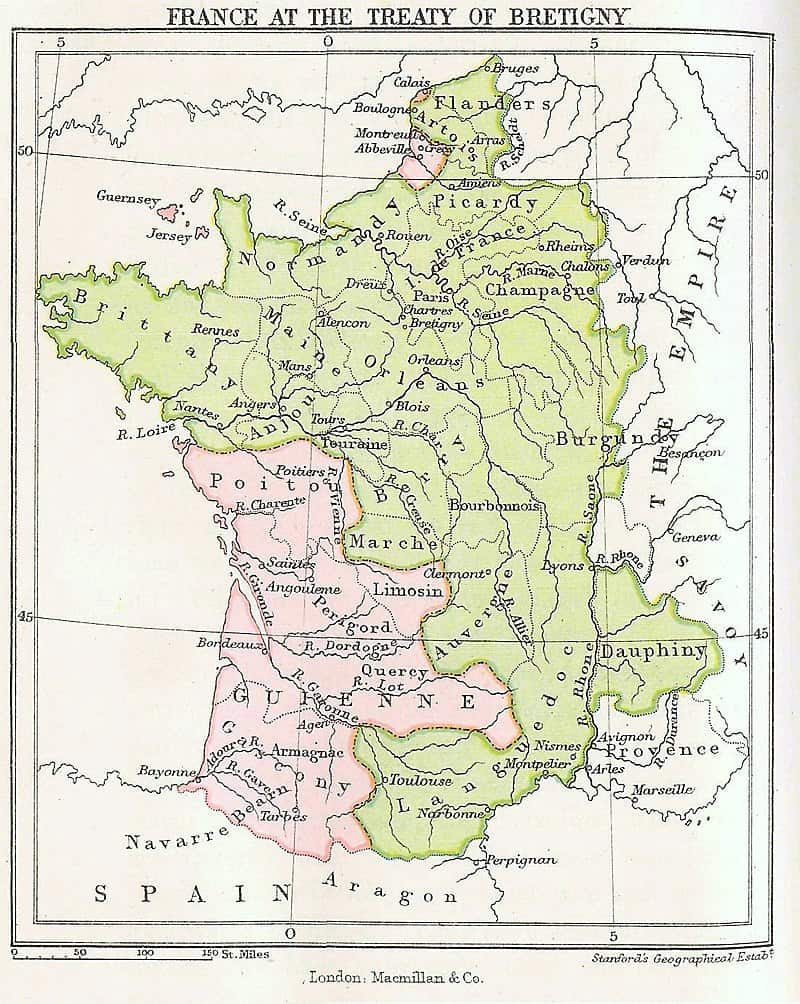

- Edward III acquired, besides Guyenne and Gascony, Poitou, Saintonge, Aunis, Agenais, Périgord, Limousin, Quercy, Bigorre, the countship of Gauré, Angoumois, Rouergue, Montreuil-sur-Mer, Ponthieu, Calais, Sangatte, Ham and the countship of Guînes, in full sovereignty and clear of homage.

- The title of Duke of Aquitaine was replaced by Lord of Aquitaine.

- Edward III relinquished the Duchy of Touraine, the countships of Anjou and Maine, and independence of Brittany and Flanders.

- Edward III renounced all claims to the French throne.

- France agreed to ransom John II at a cost of three million gold coins.

- The Treaty of Brétigny marked the end of the Edwardian War. It was later ratified as the Treaty of Calais on 24 October 1360.

- John II, who had been held captive in England, was allowed to be released after a payment of a million gold coins in exchange for two of his sons, several princes and nobles, four inhabitants of Paris, and two residents from each of the main French towns.

- The French king travelled back to France and attempted to raise funds for the remaining ransom.

- In 1362, his son Louis of Anjou, one of the hostages held by the English in Calais, successfully fled from captivity.

- Honouring the agreement he made with England, John II returned to captivity in London. He died in imprisonment in 1364.

- John II’s son, Charles V, succeeded to the French throne. In 1369, he clashed with the Black Prince regarding the English domains in Aquitaine. This resulted in the outbreak of the second phase of the Hundred Years’ War, effectively ending the nine-year peace brought about by the Treaty of Brétigny.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Map-_France_at_the_Treaty_of_Bretigny.jpg/800px-Map-_France_at_the_Treaty_of_Bretigny.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/Edward_III_of_England_%28Order_of_the_Garter%29.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/The_battle_of_Poitiers.jpg