Amritsar Massacre Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Amritsar Massacre to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Historical Background

- Prelude

- The Massacre

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Amritsar Massacre!

The Amritsar Massacre, commonly known as the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, happened on 13 April 1919 at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, British India. In the beginning, it was just a peaceful protest against the Rowlatt Act, which indefinitely prolonged the emergency measures of preventative indefinite detention, imprisonment without trial and judicial review, as well as the jailing of some activists. The peaceful protest resulted in a brutal event. The brutality was caused by an order given by Brigadier-General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer. Dyer was the temporary Brigadier-General at that time, tasked by the Governor of Punjab with restoring order there.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

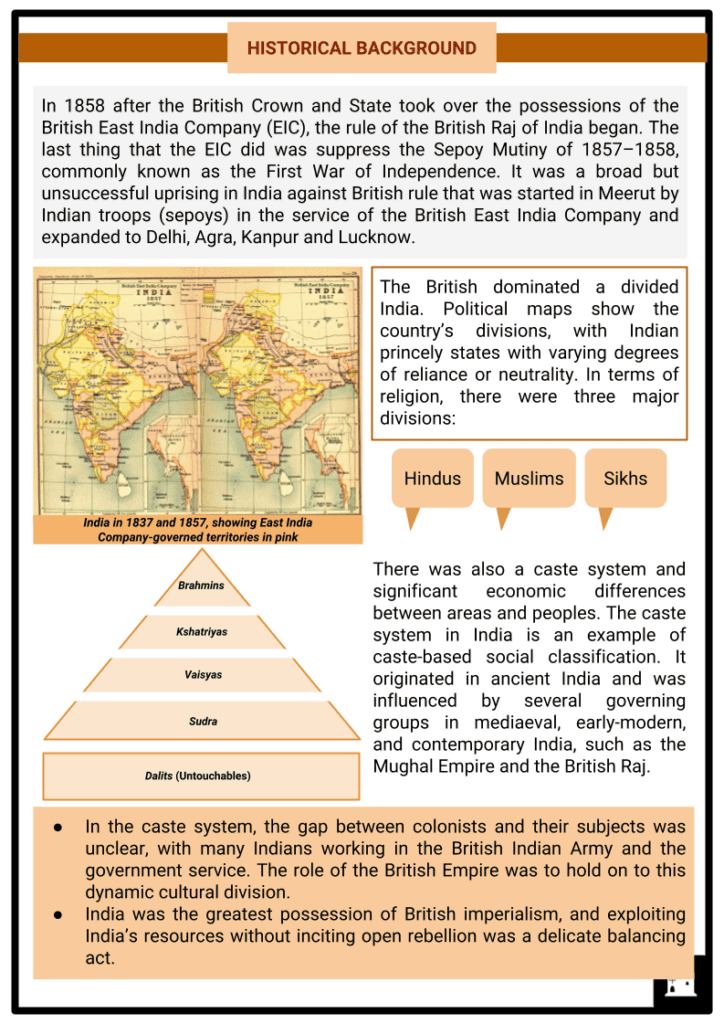

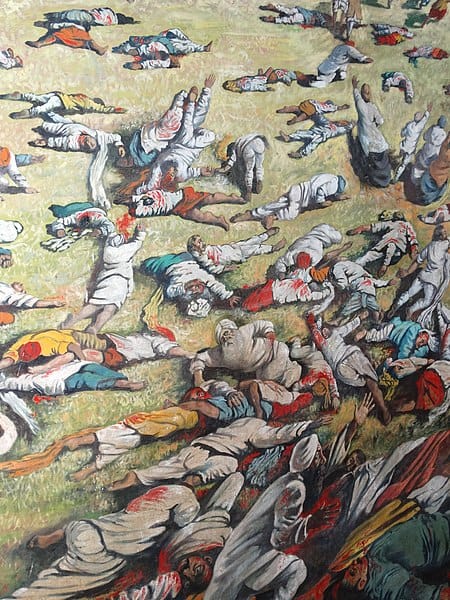

- In 1858 after the British Crown and State took over the possessions of the British East India Company (EIC), the rule of the British Raj of India began. The last thing that the EIC did was suppress the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857–1858, commonly known as the First War of Independence. It was a broad but unsuccessful uprising in India against British rule that was started in Meerut by Indian troops (sepoys) in the service of the British East India Company and expanded to Delhi, Agra, Kanpur and Lucknow.

- The British dominated a divided India. Political maps show the country’s divisions, with Indian princely states with varying degrees of reliance or neutrality. In terms of religion, there were three major divisions: Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs.

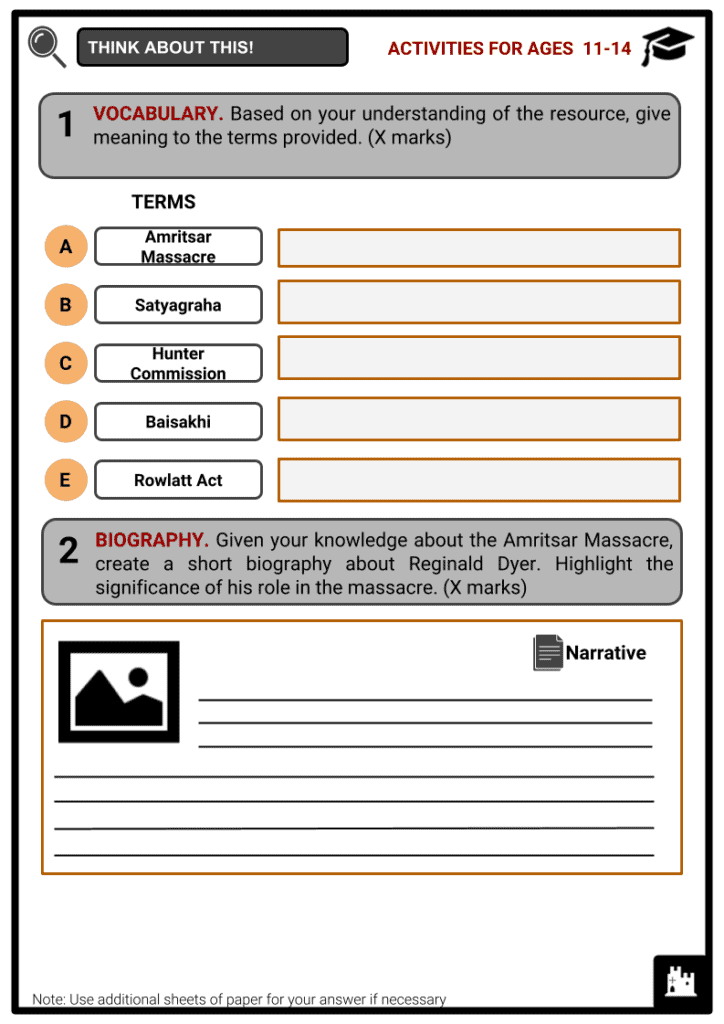

- There was also a caste system and significant economic differences between areas and peoples. The caste system in India is an example of caste-based social classification. It originated in ancient India and was influenced by several governing groups in mediaeval, early-modern, and contemporary India, such as the Mughal Empire and the British Raj.

- In the caste system, the gap between colonists and their subjects was unclear, with many Indians working in the British Indian Army and the government service. The role of the British Empire was to hold on to this dynamic cultural division.

- India was the greatest possession of British imperialism, and exploiting India’s resources without inciting open rebellion was a delicate balancing act.

- The First World War aggravated colonial tensions in India. Indians had fought to defend British interests in India and elsewhere, yet many Indian troops could not find meaningful work when they came back to India after the war.

- India had also contributed considerable equipment and raw supplies to the war effort, highlighting the British administration’s shortcomings more than ever. The Punjab region in northern India was considered a particularly risky location for British interests.

- The Indians of many faiths in the Punjab region were impressively united and politically active, with organisations such as the Ghadar Party dedicated to driving the British out of India.

- After facing difficulties brought about by war, the Rowlatt Act of March 1919 followed. The act authorised the British administration to continue using control in the government and giving them the authority to imprison anyone that they thought was against them.

India in 1837 and 1857, showing East India Company-governed territories in pink

ROWLATT ACT

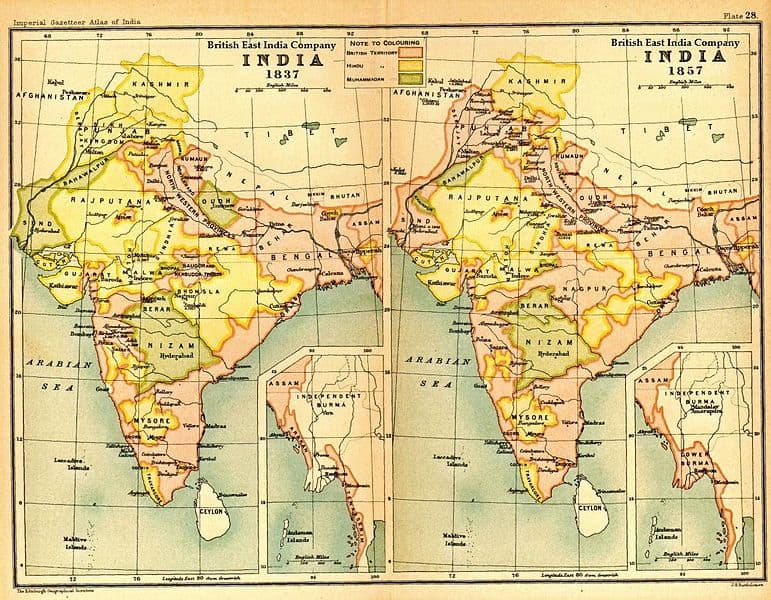

- The British Colonial Government issued the Rowlatt Act, which empowered police to arrest anyone, even for no reason. The act’s objective was to quell the country’s burgeoning nationalist outburst. Mahatma Gandhi encouraged people to protest the act through satyagraha, which implied a unique approach of mass protest that emphasises the power of truth, and the need to search for truth. The Rowlatt Act, named after its president, Sir Sidney Rowlatt, was passed on the recommendations of the Rowlatt Committee and effectively authorised the British government to detain any person suspected of terrorism living in British India. This act also allowed the colonial authorities power to deal with all revolutionary activities. The following were the highlights of the act:

- Anyone accused of terrorist activity could be detained for up to two years without a trial.

- A trial could be conducted without a jury.

- Police could detain people without legal reasons.

- A search warrant was not required.

- Among other Indian leaders, Mahatma Gandhi was harshly critical of the act, arguing that not everyone should be punished for individual political offences. Members of the All-India Muslim League, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Mazharul Haque and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, resigned from the Imperial Legislative Council to protest the act.

- Gandhi and others believed constitutional opposition to the proposal would be futile, so they staged a hartal on 6 April. A hartal was an act in which Indians ceased enterprises and went on strike after strike, fasting, praying, and holding public gatherings in opposition to the Rowlatt Act and people were encouraged to carry out civil disobedience to show their disagreement at the Rowlatt Act.

Sir Sidney Rowlatt - However, the success of the hartal in Delhi was overshadowed by heightened tensions, which resulted in riots in Punjab, Delhi and Gujarat. Gandhi discontinued the resistance after concluding that Indians were unwilling to take a stand consistent with the ideal of nonviolence, an essential component of satyagraha.

- The Rowlatt Act went into effect on 21 March 1919. The protest movement in Punjab was quite strong, and on 10 April, two congress leaders, Dr Satyapal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, were arrested and covertly transferred to Dharamsala.

PRELUDE

- The situation in India, especially in Punjab, was deteriorating rapidly due to factors including disruptions of rail, telegraph, and systems of communication. Indian army officers thought that there would be revolts, so they prepared themselves for this. Michael O’Dwyer, the British Lieutenant-Governor at that time, believed there was a sign of conspiracy for a coordinated rebellion planned around May.

BRIEF TIMELINE BEFORE THE AMRITSAR MASSACRE

10 APRIL 1919

- A demonstration was held outside the home of Miles Irving, the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar. The protest was held to urge the immediate release of Satyapal and Kitchlew, two prominent figures of the Indian Independence Movement who had been detained for organising a gathering to criticise the passage of the Rowlatt Act and British government rule in India.

- Satyapal and Kitchlew were supporters of Gandhi’s satyagraha movement. A military picket fired into the crowd, killing several demonstrators and sparking a chain of events. Riotous crowds set fire to British banks and killed some British citizens.

11 APRIL 1919

- Fearing for the safety of the more or less 600 Indian children under her care, Marcella Sherwood, an elderly English missionary, was on her way to close the schools and send the youngsters home.

- A mob attacked her while travelling through the narrow street of the Kucha Kurrichhan. She was saved by some local Indians, including the father of one of her students, who concealed her from the mob and then smuggled her to Gobindgarh Fort for safety. Amritsar was peaceful for the next two days. Still, violence continued in the outlying regions of Punjab. Railway connections were severed, telegraph poles were destroyed and government buildings were set on fire.

13 APRIL 1919

- The British government had decided to declare martial law in most of Punjab. The legislation curtailed several civil liberties, notably the right to assemble in groups of more than four persons.

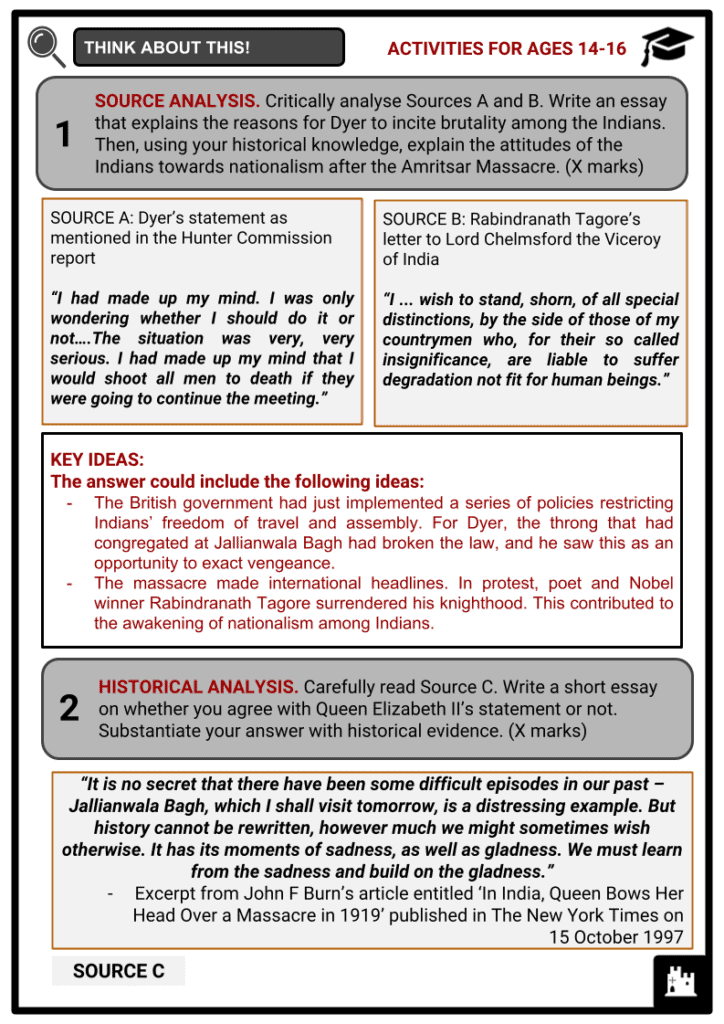

THE MASSACRE

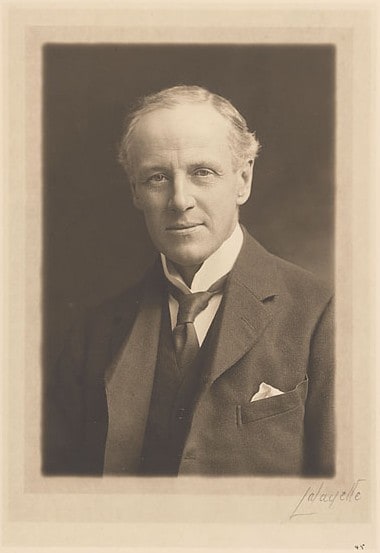

- On Sunday 13 April 1919, Reginald Dyer, the acting Brigadier-General during this period, was convinced a significant insurrection could take place so he banned all meetings and public gatherings.

- People were enjoying a harvest festival known as the Baisakhi. Dyer, accompanied by many municipal officials, marched across the city and announced the establishment of a pass system for entering and leaving Amritsar. He also announced a curfew that night and banned all public gatherings of four or more people. Meanwhile, word of mouth and plainclothes investigators in the crowd provided local police with information about the planned meeting in Jallianwala Bagh.

- Thousands of Indians had assembled in Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh Garden near the Harmandir Sahib by mid-afternoon on 19 April. Many of those present had been to the Golden Temple earlier in the day and passed through the Bagh on their way home.

- Aside from pilgrims, Amritsar had filled up in the previous days with farmers, traders and merchants attending the annual Baisakhi horse and cow exhibition.

Reginald Dyer - According to Nigel Collett’s book The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer, Dyer arranged for an aeroplane to fly over the area of Bagh and check the crowd, which he reported was around 6,000. However, the Hunter Commission estimates that a group of 10,000 to 20,000 had gathered by the time Dyer arrived.

- Colonel Dyer and Deputy Commissioner Irving, the top civil authority in Amritsar, took no action to prevent the crowds from forming or to disperse them quietly. This became a significant charge brought against both Dyer and Irving.

- Dyer ordered his forces to block the main entrances and started shooting towards the crowded areas of the mob in front of the available tiny exits, where frantic crowds were attempting to flee the Bagh.

- The shooting lasted about ten minutes. Unarmed civilians were killed, including men, women, elderly and children. Only after ammo supplies were nearly depleted was a ceasefire order issued. The troops had used roughly one-third of their ammunition.

- As mentioned in Collet’s The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer, the following was the purpose and result of Dyer’s command.

- The purpose was not to disperse the meeting but rather to punish the Indians for their disobedience.

- As a result, between 200 and 300 people were murdered, and Dyer claimed that his forces shot 1,650 rounds.

AFTERMATH

- Because of the incident that resulted in the deaths of many people, Indian loyalists abandoned their allegiance to the British government and became nationalists. O’Dwyer requested that martial law must be extended in Amritsar and other places. Viceroy Lord Chelmsford, a British diplomat who served as Viceroy of India from 1916 to 1921, agreed to his request.

- However, both Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill and former United Kingdom Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith publicly criticised the attack, with Churchill calling it ‘unutterably monstrous’ and Asquith referring to the incident as one of the worst and most brutal outrages in British history. Churchill stated in a House of Commons discussion on 8 July 1920:

“The crowd was unarmed, except with bludgeons. It was not attacking anybody or anything ... When fire had been opened upon it to disperse it, it tried to run away. Pinned up in a narrow place considerably smaller than Trafalgar Square, with hardly any exits, and packed together so that one bullet would drive through three or four bodies, the people ran madly this way and the other. When the fire was directed upon the centre, they ran to the sides. The fire was then directed to the sides. Many threw themselves down on the ground, the fire was then directed down on the ground. This was continued to 8 to 10 minutes, and it stopped only when the ammunition had reached the point of exhaustion.”

- According to Jon A Cloake’s book Britain in the Modern World, following Churchill’s address during the House of Commons debate, most British leaders voted against Dyer’s brutal act. Cloake stated that, despite the official condemnation, many British considered Dyer a hero for preserving the authority of British law in India.

- When the news about the massacre reached some loyalists, they immediately condemned the act of Dyer’s troops. One of them was Rabindranath Tagore, a Bengali polymath who was known as a writer, poet and philosopher. He renounced his British knighthood to show his symbolic act of protest against the British government.

HUNTER COMMISSION

- After the Secretary of State for India Edwin Montagu issued the orders on 14 October 1919, the Government of India appointed a committee to investigate the events in Punjab. It was first named the Disorders Inquiry Committee but was eventually called the Hunter Commission.

- It was named after the chairman, William Hunter, a former Solicitor-General for Scotland and Senator of the Scottish College of Justice. The commission’s aim was to investigate recent disturbances in Bombay, Delhi and Punjab, their causes, and the measures taken to deal with them.

- In October 1919, witnesses were called during the investigation and members of the commission managed to get detailed accounts and statements from witnesses.

- Dyer was called to appear before the commission in November 1919. Lord Hunter was the first one who questioned Dyer during the investigation. According to some historians, Dyer indicated that he learnt about the celebration at Jallianwala Bagh around 12.40pm that day (19 April) but made no move to prevent it. He stated that he went to the Bagh to open fire when he saw a mob gathered there.

- Dyer asserted that he aimed to instil panic throughout Punjab, lowering the moral standing of the ‘rebels’. Months after the investigation, the commission released a report in March 1920. The report concluded that:

- In the beginning, the lack of notice to disperse from the Bagh was a mistake.

- Dyer’s motivation for creating a sufficient moral effect was criticised.

- Dyer had stepped outside of his authority.

- There had been no plot to destabilise the British government.

- Numerous military superiors tolerated Dyer’s brutal act. Therefore the Hunter Commission took no punitive or disciplinary action. The Viceroy’s Executive Council’s Legal and Home Members ultimately agreed that military or legal punishment would be impossible for political reasons, notwithstanding Dyer’s cruel and brutal actions.

REACTIONS

- Indians were still enraged by the massacre. Even several pro-British rulers of independent princely states, like the Raja of Nabha, condemned Dyer’s excessive use of force. The Hunter Commission’s failure to find anyone guilty of anything in 1919, when there had indeed been so much unnecessary murder and humiliation in Punjab, demonstrated all too clearly that the British administration had sanitised history. Above all, Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement received a more extensive support base and continued striving for ‘home rule’ from 1920.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Detail_of_Mural_Depicting_1919_Amritsar_Massacre_-_Jallianwala_Bagh_-_Amritsar_-_Punjab_-_India_(12675536215).jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:India1837to1857.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_Sidney_Arthur_Taylor_Rowlatt_(cropped).jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:General-Reginald-Dyer.jpg