Appeasement Policy in the 1930s Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Appeasement Policy in the 1930s to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- History

- Conduct of Appeasement

- Perspectives on Appeasement

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Appeasement Policy in the 1930s!

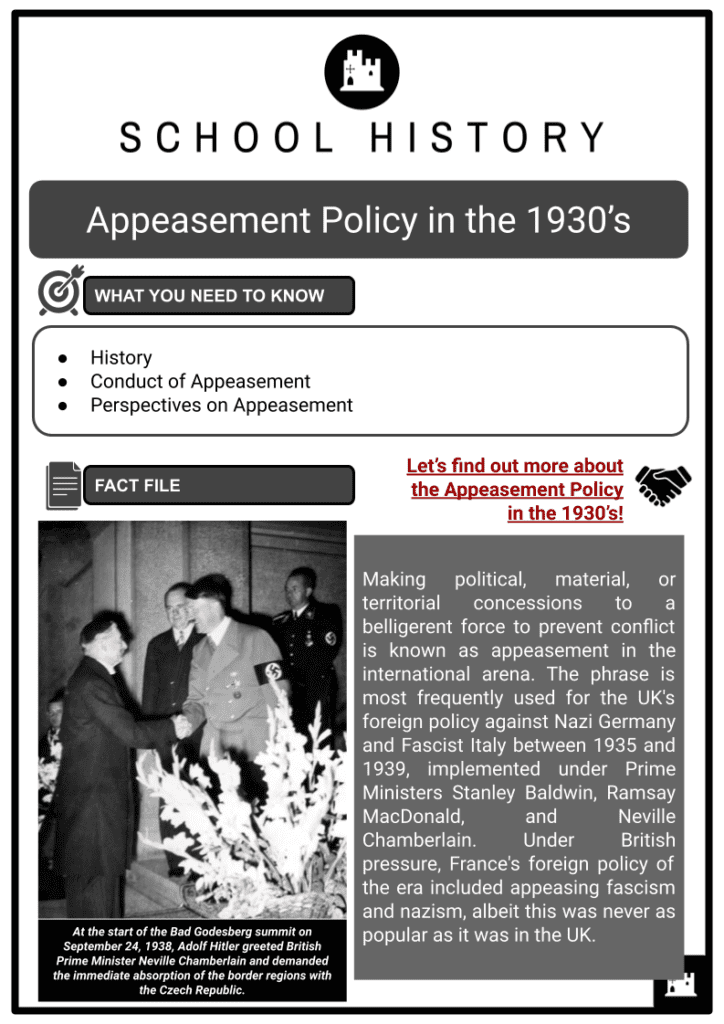

Making political, material, or territorial concessions to a belligerent force to prevent conflict is known as appeasement in the international arena. The phrase is most frequently used for the UK's foreign policy against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy between 1935 and 1939, implemented under Prime Ministers Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, and Neville Chamberlain. Under British pressure, France's foreign policy of the era included appeasing fascism and nazism, albeit this was never as popular as it was in the UK.

HISTORY

- The League of Nations dissolution and the absence of global security gave rise to Chamberlain's appeasement policy. The League of Nations was founded to prevent future wars through international cooperation and unified anti-invasion resistance after World War I.

- If they were attacked, League members had a right to the support of other League members. The collective security strategy was intended to run parallel to efforts to achieve global disarmament and, whenever possible, be based on economic sanctions against an aggressor.

- It seemed ineffective when faced with dictatorial aggression, such as Germany's Remilitarisation of the Rhineland and Italian leader Benito Mussolini's invasion of Abyssinia.

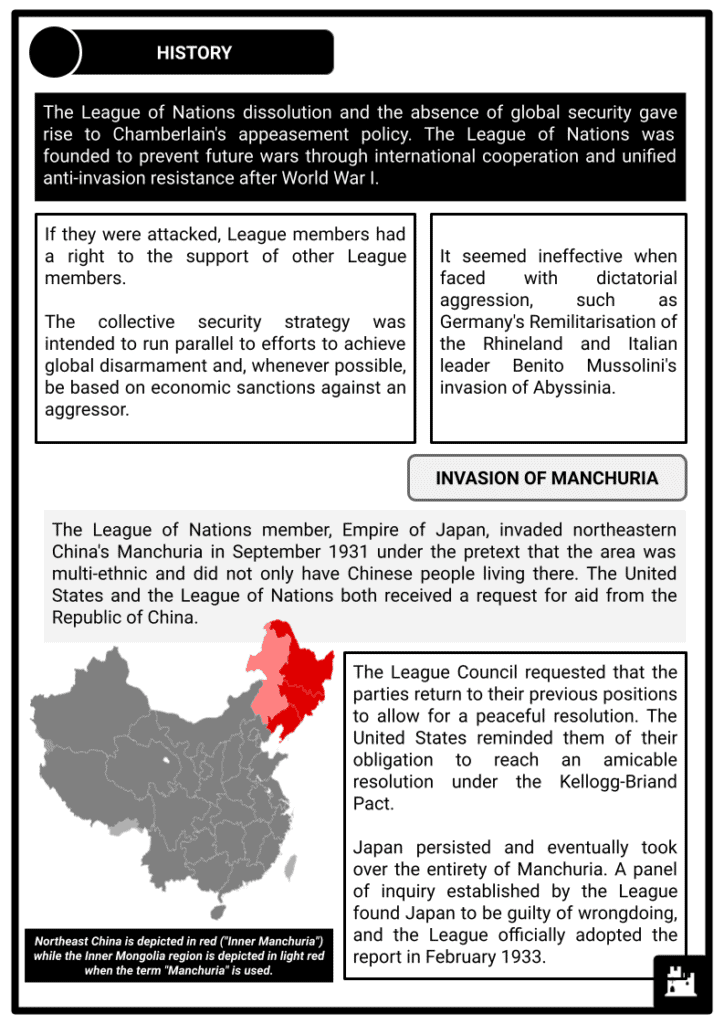

INVASION OF MANCHURIA

- The League of Nations member, Empire of Japan, invaded northeastern China's Manchuria in September 1931 under the pretext that the area was multi-ethnic and did not only have Chinese people living there. The United States and the League of Nations both received a request for aid from the Republic of China.

- The League Council requested that the parties return to their previous positions to allow for a peaceful resolution. The United States reminded them of their obligation to reach an amicable resolution under the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Japan persisted and eventually took over the entirety of Manchuria. A panel of inquiry established by the League found Japan to be guilty of wrongdoing, and the League officially adopted the report in February 1933.

- Japan resigned from the League in reaction, and the League and the U.S. did little to stop Japan's push into China. However, the U.S. declared the Stimson Doctrine and refused to acknowledge Japan's conquest, which contributed to a change in U.S. policy in the late 1930s that favoured China over Japan.

ANGLO-GERMAN NAVAL AGREEMENT

- In this 1935 agreement, the United Kingdom consented to allow Nazi Germany to begin rebuilding its fleet, including its U-boats, even though Hitler had already violated the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles.

ABYSSINIAN CRISIS

- Benito Mussolini, the Italian prime minister, desired to rule Ethiopia as an imperial power. Eritrea and Somalia, two neighbouring countries, were already in Italy's possession. At Walwal, close to the border between British and Italian Somaliland, Royal Italian Army and Imperial Ethiopian Army troops engaged in combat in December 1934. Italian troops took control of the disputed territory, and 50 Italians and 150 Abyssinians were killed.

- When Italy demanded an apology and restitution from Abyssinia, the latter turned to the League, with Emperor Haile Selassie making a unique personal appeal to the Geneva assembly. The League convinced both parties to seek a settlement under the Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928, Italy continued to advance troops, and Abyssinia once more appealed to the League.

- October 1935, Abyssinia was the target of an attack by Mussolini. Coal and oil were not included in the penalties the League imposed since they were believed to be a war starter, so Italy was labelled the aggressor. Germany and the United States were not League members, and sanctions were not imposed on Albania, Austria, or Hungary.

- April 1935, Italy joined Britain and France in denouncing the rearmament of Germany. France was eager to appease him to prevent Mussolini from forming an alliance with Germany. In addition to leading the way in enacting sanctions and deploying a naval fleet into the Mediterranean, Britain was less antagonistic toward Germany.

- November 1935, During their private talks, French Prime Minister Pierre Laval and British Foreign Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare decided to hand over two-thirds of Abyssinia to Italy. Hoare and Laval were obliged to quit as a result of the public backlash after the press published the details of the meetings.

- May 1936, Sanctions could not discourage Italy from capturing Addis Abeba and installing Victor Emmanuel III as Ethiopia's Emperor. The League stopped enforcing punishments in July. This incident badly damaged the League's reputation because the sentences were ineffective and appeared readily abandoned.

CONDUCT OF APPEASEMENT

- Neville Chamberlain became prime minister after Stanley Baldwin resigned in 1937. Chamberlain followed an appeasement and rearmament strategy. Chamberlain's reputation as an appeaser in Austria was left as a rump state with the interim name Deutschösterreich when the German Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire were split up in 1918, with the vast majority of Austrian Germans preferring to join Germany.

ANSCHLUSS

- The Weimar Republic's and the First Austrian Republic's constitutions both had the unification objective, which was supported by democratic parties. However, the ascent of Adolf Hitler tempered the Austrian government's enthusiasm for such a scheme. Hitler, who was born in Austria, had been a pan-German from an early age and had advocated for a Greater German Reich from the start of his political career. Kurt Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, wanted to strengthen connections with Italy but looked to Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania instead.

- Hitler violently objected to this. The Austrian Nazi Party attempted a putsch in January 1938, and some members were put in prison as a result. It is primarily based on Schuschnigg discussions with Hitler in 1938 on Czechoslovakia.

- The German Propaganda Ministry released press accounts of riots occurring in Austria and widespread calls for German troops to restore order. Hitler gave Schuschnigg until 11 March to hand over all authority to the Austrian Nazis or face an invasion. Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador in Berlin, lodged a complaint against using coercion against Austria with the German administration.

- Seyss-Inquart was elected in place of Schuschnigg after the latter realised that neither France nor the United Kingdom would actively back him. Seyss-Inquart subsequently requested the assistance of German troops to restore order. The German Wehrmacht reached the Austrian border on 12 March. They encountered no opposition and were welcomed by cheering Austrians.

- The Wehrmacht's equipment was tested for the first time in this invasion. Ostmark, a German province, was created out of Austria, with Seyss-Inquart as its governor. On 10 April, a referendum was held, with 99.73% of the vote officially indicating favour. Even though the Allies who won World War One had forbidden Austria and Germany from joining, their response to the Anschluss was muted.

Kurt Schuschnigg

MUNICH AGREEMENT

- Following the Versailles Settlement, Czechoslovakia was established, with the Czech part's area roughly matching the Czech Crown territories as they had previously existed under Austria-Hungary. It covered Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia. It had border regions with the Sudetenland, which had a predominantly German population, and areas with sizable numbers of other ethnic minorities (notably Hungarians, Poles, and Ruthenes).

- The Sudeten German Party, under the direction of Konrad Henlein, pushed for independence in April 1938 and then threatened, in Henlein's words, "direct action to bring the Sudeten Germans within the frontiers of the Reich."

- Faced with the possibility of a German invasion, Chamberlain travelled to Berchtesgaden on 15 September to meet with Hitler face-to-face. Hitler now asked that Chamberlain approve the incorporation of the Sudeten territories into Germany rather than only Sudeten self-government inside Czechoslovakia.

- Edvard Bene, the president of the Czech Republic, was instructed by Britain and France to turn over to Germany all territory having a German majority. Hitler escalated his hostility toward Czechoslovakia and gave the go-ahead for forming a Sudeten German paramilitary group, which later carried out terrorist assaults on Czech targets.

Hitler, Mussolini, Chamberlain, Daladier, and Ciano are shown in a photo taken before they signed the Munich Agreement, which granted Germany control of the Czechoslovak border regions.

PERSPECTIVES ON APPEASEMENT

- Those who supported the appeasement strategy were swiftly criticised as it failed to deter conflict. Those in charge of British or other democratic nations' diplomacy grew to view appeasement as something to be avoided. The few individuals who opposed appeasement, however, were viewed as "voices in the wilderness whose sensible counsels were mostly disregarded, with almost catastrophic results for the nation in 1939–1940."

- MacDonald and Baldwin's policies were primarily carried on by Chamberlain's administration, which enjoyed widespread support until the Munich Agreement failed to prevent Hitler from entering Czechoslovakia. Between 1919 and 1937, the term "appeasement" was considered appropriate to describe the pursuit of peace.

- As mass labour unrest returned to Britain and news of Stalin's bloody purges alarmed the West, anti-communism was occasionally acknowledged as a determining factor. Most individuals in command of British foreign policy in the 1930s, as well as notable academics, journalists, and members of the royal family, like King Edward VIII and his successor, George VI, all supported appeasement. Although Churchill claimed their supporters were split, most Conservative MPs were in favour. In 1936, Churchill led a group of prominent Conservative lawmakers to convey their concern to Baldwin about the rapidity of German rearmament and the fact that the country of Britain was lagging.

- The fact that "Churchill's current criticism of totalitarian governments other than Hitler's Germany was at best muted" has been obscured by his role in creating the post-war consensus against appeasement and his subsequent leadership of Britain during the war.

- In the House of Commons session, he didn't begin consistently criticising the National Government's conduct of foreign policy until May 1938. He seems to have been persuaded by Sudeten German leader Henlein in the spring of 1938 that a fair settlement could be reached if Britain could invite the government of Czech to make concessions to the German minority.