Bantustans Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Bantustans to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Creation of Bantustans

- Life of People in Bantustans

- Dissolution of Bantustans

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Bantustans!

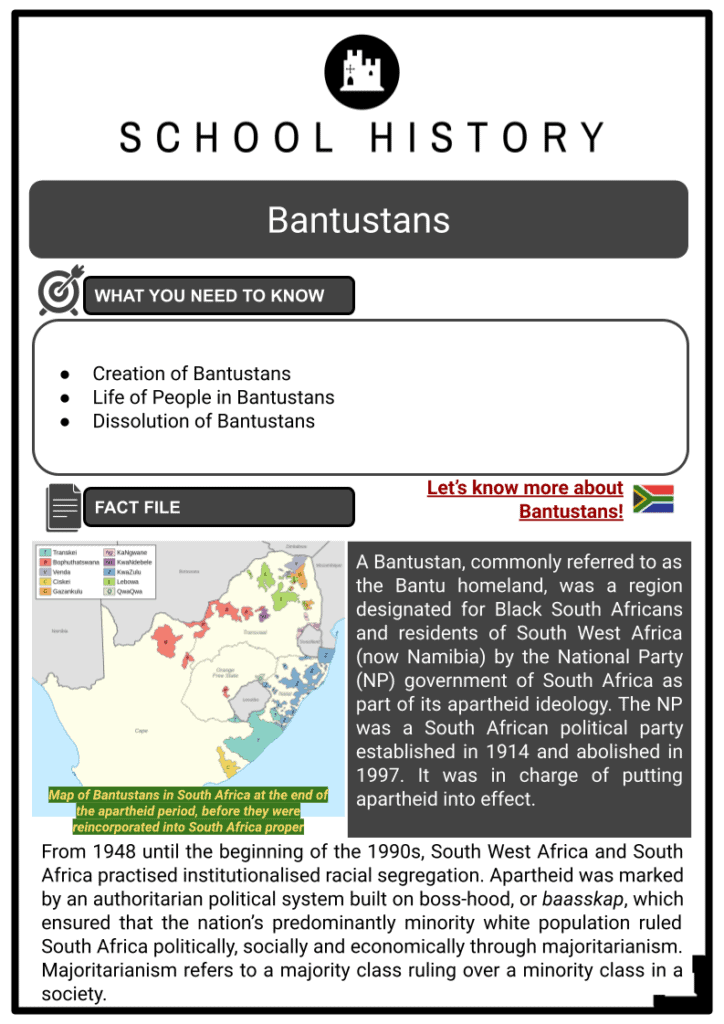

A Bantustan, commonly referred to as the Bantu homeland, was a region designated for Black South Africans and residents of South West Africa (now Namibia) by the National Party (NP) government of South Africa as part of its apartheid ideology. The NP was a South African political party established in 1914 and abolished in 1997. It was in charge of putting apartheid into effect. From 1948 until the beginning of the 1990s, South West Africa and South Africa practised institutionalised racial segregation. Apartheid was marked by an authoritarian political system built on boss-hood, or baasskap, which ensured that the nation’s predominantly minority white population ruled South Africa politically, socially and economically through majoritarianism. Majoritarianism refers to a majority class ruling over a minority class in a society.

CREATION OF BANTUSTANS

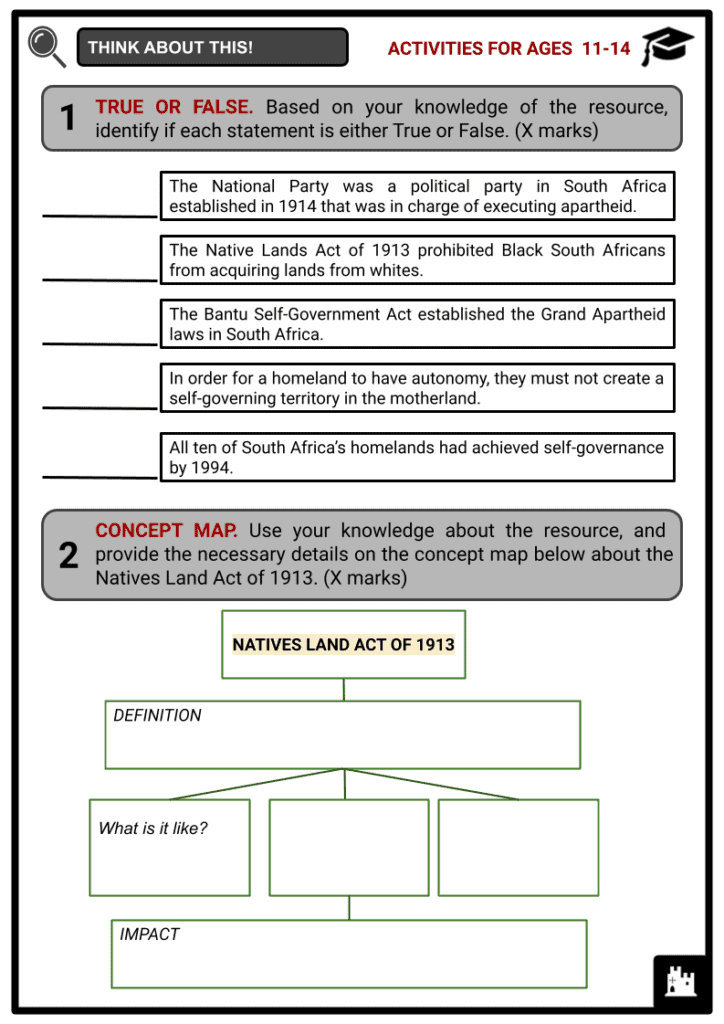

- Starting in 1913, South African administrations with a white majority separated the Black South Africans from the white population by establishing reserves for them. Black South Africans were only allowed to own 7% of the nation’s land due to the Natives Land Act of 1913. The Natives Land Act was the first significant legislation on segregation. The act prohibited Black people from purchasing land from white people and the reverse.

- Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd, the Minister for Native Affairs under the NP, came to power in 1948 and built on this segregation by enacting several grand apartheid laws, including the Group Areas Acts and the Natives Resettlement Act of 1954, which changed South African society so that white people would make up the majority of the population.

- The creation of Bantustans was vital in order to have a majority of white people.

- Black people would be stripped of their South African citizenship and right to vote, preserving white supremacy over South Africa.

- According to Verwoerd, the Bantustans were the original homes of South Africa’s Black population. The Bantu Authorities Act was introduced in 1951 by Prime Minister Daniel François Malan’s administration to create homelands designated for the nation’s Black ethnic nations.

- Over time, a Black South African ruling class with a vested financial and personal stake in preserving the homelands began to form. While this contributed to the political stability of the homelands to some extent, their status remained dependent on South African assistance.

- When the Bantu Self-Government Act was passed in 1959, it established a strategy known as Separate Development and increased the role of the homelands. As a result, the homelands could establish themselves long-term as autonomous nations and eventually as nominally complete independent governments.

BANTU SELF-GOVERNMENT ACT

- Established the Grand Apartheid laws call for the permanent division of South Africa into national homelands.

- Most of the nation would be ruled by the Afrikaners (indigenised Dutch), while the African population was split into eight ethnic groups.

- A Commissioner-General was appointed to oversee the development of each Black nation.

- Black people were supposed to exercise their political rights in these homeland enclave states.

For each homeland, the procedure of being an autonomous nation was to be completed in a succession of four key steps:

-

- combining the reserves for the various tribes (formally referred to as nations since 1959) under a single Territorial Authority

- the creation of a legislative body with restricted self-government for each homeland

- creation of a self-governing territory in the motherland

- the declaration of the country’s complete nominal independence

- As its institutional development began before the Bantu Self-Government Act, the homeland of Transkei acted in many ways as a testing ground for apartheid policies and, as a result, its attainment of self-government and independence was implemented earlier than for the other homelands.

- As part of his approach to apartheid, John Vorster, Verwoerd’s successor as Prime Minister, intensified this policy. However, this policy’s real goal was to carry out Verwoerd’s initial vision of converting the little remaining privileges that Black South Africans had as citizens into homeland nationals rather than South Africans.

- The homelands were urged to choose independence because doing so would significantly decrease the number of Black South African citizens. The process of establishing the legal framework for this strategy was completed by the Black Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970, which formally recognised all Black South Africans as citizens of the homelands even if they resided in ‘White South Africa’, and the Bantu Homelands Constitution Act of 1971, which offered a general roadmap for the stages of constitutional development for all homelands, aside from Transkei.

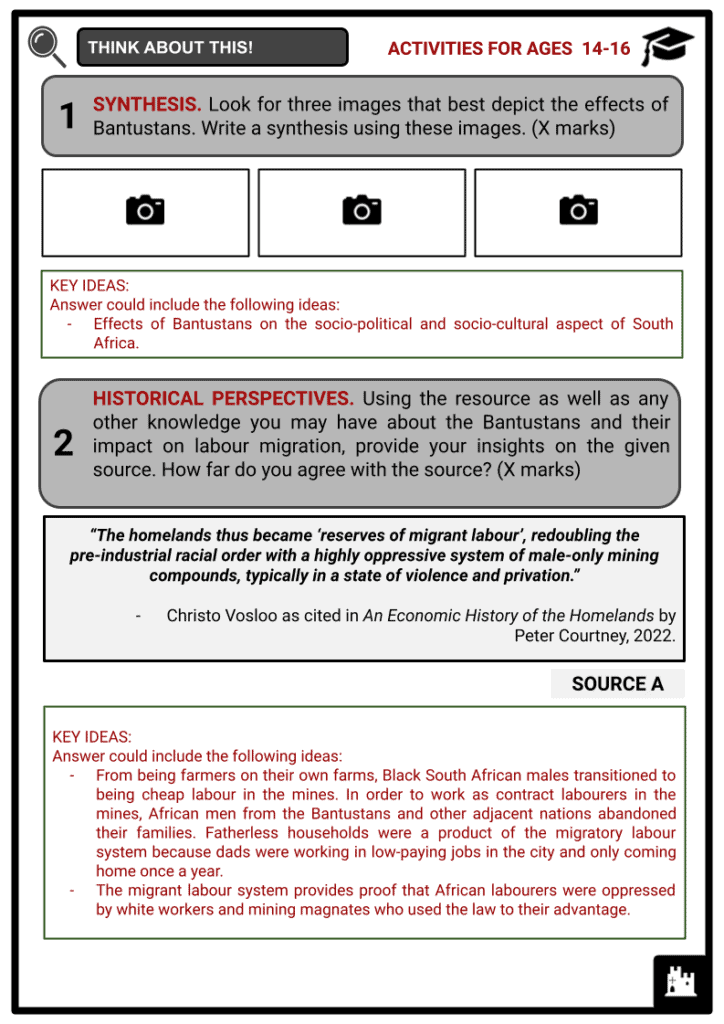

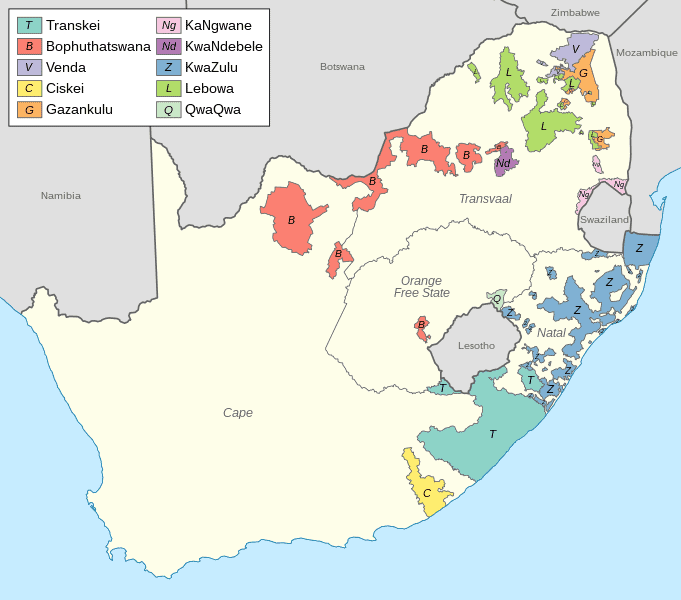

- All ten of South Africa’s homelands had achieved self-governance by 1984, and four of them (Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei) were formally recognised as independent states between 1976 and 1981.

- The government made it evident that eradicating all Black people from South Africa was its ultimate goal. On 7 February 1978, Connie Mulder, the Minister of Plural Relations and Development, stated to the House of Assembly:

“If our policy is taken to its logical conclusion as far as the Black people are concerned, there will be not one Black man with South African citizenship ... Every Black man in South Africa will eventually be accommodated in some independent new state in this honourable way and there will no longer be an obligation on this Parliament to accommodate these people politically.”

LIFE OF PEOPLE IN BANTUSTANS

- The Bantustans had few local job prospects and a general lack of wealth. However, there were some opportunities for Black people to prosper and some infrastructure and education developments.

- All apartheid laws were repealed following the independence of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei. The Bantustans’ laws were different from those of South Africa as a whole. The elite of South Africa frequently took advantage of these distinctions, for instance, by building massive casinos like Sun City in Bophuthatswana.

Bophuthatswana in red - Bophuthatswana was the richest of the Bantustans since it also had platinum deposits and other natural resources. However, the South African government’s large subsidies were the only thing keeping the homelands afloat. For instance, by 1985, 85% of Transkei’s income was coming from direct transfer payments from Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative capital.

- The governments of the Bantustans were always corrupt, and little income was distributed to the locals, who were compelled to look for work as guest workers in South Africa proper. Millions of individuals had to work for extended periods away from their homes in frequently awful conditions. On the other hand, because the homeland established industrial locations like Zone 15 and Babelegi, only 40% of Bophuthatswana’s population worked outside the homeland.

- Even though some of the Bantustans’ leaders successfully gained support, most people saw them as apartheid regime sympathisers.

- Most homeland leaders had an ambivalent attitude towards their homelands’ independence: the majority were sceptical, remained cautious, and avoided making a firm decision. Some outright rejected it because they disapproved of separate development, while others thought that nominal independence could help them strengthen their power bases.

- State President P W Botha said in January 1985 that Black residents of South Africa’s territorial jurisdiction would no longer be denied South African citizenship in favour of Bantustan citizenship. They could reapply for South African citizenship within the independent Bantustans. F W de Klerk spoke on behalf of the NP during the 1987 general election and claimed that:

“..every effort to turn the tide [of black workers] streaming into the urban areas failed. It does not help to bluff ourselves about this. The economy demands the permanent presence of the majority of Blacks in urban areas ... They cannot stay in South Africa year after year without political representation.”

- De Klerk, who took over for Botha as State President in 1989, declared in March 1990 that his administration would not grant any more Bantustans independence. The apartheid system relied on the Bantustans as one of the critical foundations of its strategy in dealing with the Black population, and the notion of separate development remained in place. Until 1990, efforts to persuade self-governing homelands to choose independence persisted, and occasionally, the governments of self-governing homelands expressed interest in doing so.

DISSOLUTION OF BANTUSTANS

- Following the Section 1 and Schedule 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, all Bantustans – both ostensibly independent and self-governing – were dismantled with the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1994. Bantustans were reincorporated into the Republic of South Africa with effect from 27 April 1994.

Logo of the ANC - The African National Congress (ANC), a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, was at the forefront of the effort to accomplish this as a critical component of its reform agenda.

- The reincorporation process was largely peaceful, despite some opposition from the local elites who stood to lose out on the homelands’ potential for money and political influence. It was highly challenging to demolish the Bophuthatswana and Ciskei homelands. South African security forces were forced to take action to diffuse a political crisis in Ciskei in March 1994.

- The majority of the nation was formally divided into new provinces beginning in 1994. However, some former Bantustan or homeland leaders have played a part in South African politics since they were abolished. While others joined the ANC, some entered their parties in the first non-racial election.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What are Bantustans?

Bantustans, also known as homelands, were areas in South Africa during the apartheid era designated semi-autonomous territories for various ethnic groups, primarily Black South Africans. The intention was to segregate and marginalise non-white populations from the white-controlled areas.

- Who are the Bantustans in South Africa?

Each Bantustan was intended to be a separate territorial entity for a specific ethnic group, per the apartheid government's policy of racial segregation. The ten Bantustans included Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, Ciskei, Gazankulu, KaNgwane, KwaNdebele, KwaZulu, Lebowa, and QwaQwa.

- When were Bantustans established?

The Bantustan policy was formalised in the 1950s under the apartheid regime in South Africa. The first Bantustan, Transkei, was created in 1959. Over time, ten Bantustans were established.