Battle of Britain Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Battle of Britain to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- Course of the Battle

- Change in Approach

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Battle of Britain!

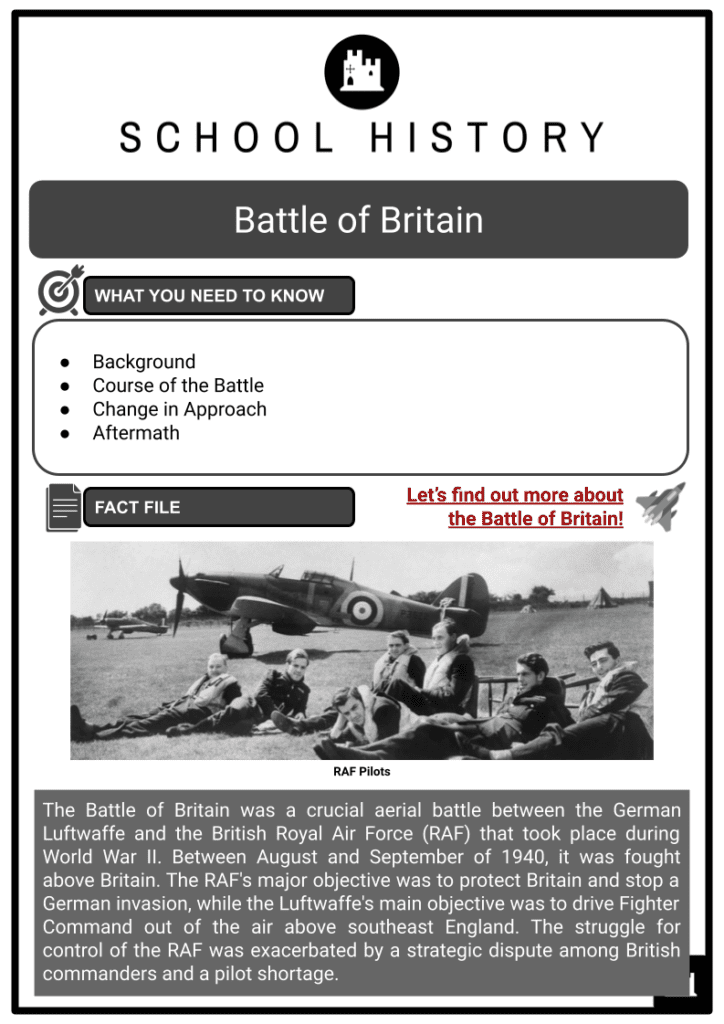

The Battle of Britain was a crucial aerial battle between the German Luftwaffe and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) that took place during World War II. Between August and September of 1940, it was fought above Britain. The RAF's major objective was to protect Britain and stop a German invasion, while the Luftwaffe's main objective was to drive Fighter Command out of the air above southeast England. The struggle for control of the RAF was exacerbated by a strategic dispute among British commanders and a pilot shortage.

BACKGROUND

- Following the collapse of France in June 1940, only Britain remained to confront the rise of Nazi Germany. The British Expeditionary Force was able to successfully evacuate most of its troops from Dunkirk, but it was forced to abandon much of its heavy machinery. Adolf Hitler first hoped that Britain would file for a negotiated peace because he did not enjoy the notion of having to attack Britain. This optimism was immediately dashed when Britain's determination to fight to the end was reaffirmed by incoming Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

- Hitler responded by directing the start of the invasion of Great Britain on 16 July. This strategy, known as Operation Sea Lion, called for an invasion in August. The annihilation of the Royal Air Force was a crucial requirement for the invasion since the Kriegsmarine had been severely depleted in prior wars, giving the Luftwaffe air control over the Channel. The Luftwaffe would be able to keep the Royal Navy at bay when German forces landed in southern England with this in hand.

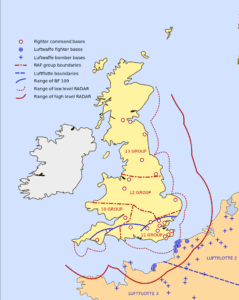

- Hitler used Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, to destroy the RAF. The flamboyant and arrogant Göring, a veteran of World War I, had successfully led the Luftwaffe throughout the early operations of the conflict. He repositioned his troops for the next conflict, bringing three Luftflotten (air fleets) to bear on Britain. Field Marshals Hugo Sperrle and Albert Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 and 3 would launch attacks from bases in France and the Low Countries, respectively, while Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff's Luftflotte 5 would do so from bases in Norway.

Hitler and Göring - The Luftwaffe was primarily created to offer aerial support for the blitzkrieg style of attack used by the German Army; therefore, it was not well-suited for the kind of strategic bombing that would be needed in the next fight. Even though its primary fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, was on par with the greatest British aircraft, its operating range would restrict the amount of time it could spend over Britain.

- The twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110 assisted the Bf 109 at the opening of the fight. The Bf 110 was a failure in its intended function as a long-range escort fighter because it rapidly exposed itself to the more agile British aircraft.

- The Luftwaffe depended on three older twin-engine bombers: the Heinkel He 111, Junkers Ju 88, and Dornier Do 17, as it lacked a four-engine strategic bomber. The single-engine Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber assisted them. The Stuka was a weapon that was effective in the early fights of the war, but it finally proved to be quite weak against British fighters and was removed from the conflict.

COURSE OF THE BATTLE

- Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, the commander of Fighter Command, was tasked with protecting Britain from the air. Dowding, who went by the moniker "Stuffy," had assumed control of Fighter Command in 1936. He had worked relentlessly to assure that the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire, the RAF's two primary fighters, were developed. The former was a little underpowered but was still capable of out-turning the German fighter, while the latter was a match for the BF 109. Dowding equipped both planes with eight machine guns because he anticipated the need for more weaponry. He frequently referred to his pilots as his "chicks" and was very protective of them.

- Dowding recognised the importance of new, advanced fighters and effective command from the ground.

- He established the Chain Home radar network and the "Dowding System," which combined radar, ground observers, raid mapping, and radio control of planes.

- He established a secured telephone network managed by RAF Bentley Priory to connect all parts.

- Dowding split command into four groups: 10 Group (Wales and West Country), 11 Group (Southeastern England), 12 Group (Midland and East Anglia), and 13 Group (Northern England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland).

- Dowding was initially set to retire in June 1939 but was urged to stay on until March 1940 due to the global situation. Later, his retirement was postponed until July and then October.

- Dowding fiercely resisted moving Hurricane squadrons over the Channel during the Battle of France to maintain strength.

- The Luftwaffe had an inaccurate assessment of Fighter Command's strength since the majority of its resources had been hoarded in Britain during earlier combat. Göring mistakenly assumed that the British had 300 to 400 planes, whereas Dowding had nearly 700. The German general thought that Fighter Command might be eliminated from the air in four days as a result. The British radar system and ground control network were known to the Luftwaffe, but it downplayed their significance and thought they formed an inflexible tactical structure for the British squadrons. The system gave squadron commanders the freedom to make appropriate decisions based on the most recent information.

- Göring expected to quickly defeat Fighter Command during a bombing campaign that lasted five weeks, from 8 August to 15 September. The initial raids targetted coastal RAF airfields and then advanced to bigger sector airfields and aircraft factories. A disagreement over tactics between Kesselring and Sperrle arose, with Kesselring wanting to continue attacking British air defenses and Sperrle wanting direct strikes on London. However, Hitler's directive forbidding the bombing of London put a stop to the argument.

- Dowding believed that avoiding major air battles and using deception tactics was the best way to use his aircraft and pilots. He aimed to make the Germans believe that Fighter Command was running low on supplies by attacking in squadron strength, causing the Luftwaffe to suffer unsustainable losses. This strategy was not popular and not supported by the Air Ministry, but Dowding believed it was necessary to prevent the German invasion. He instructed his pilots to pursue the German bombers, avoid fighter-to-fighter combat, and conduct action over Britain so that downed pilots could be quickly rescued.

Kanalkampf

- On 10 July, the Royal Air Force and Luftwaffe engaged in combat over the English Channel. German Stukas attacked British coastal convoys during these battles, which were known as the Kanalkampf or Channel Battles. Even though Churchill and the Royal Navy refused to symbolically abandon control of the Channel, Dowding was prevented from doing so from above. He would have preferred to stop the convoys rather than spend pilots and aircraft defending them. German twin-engine bombers were added as the battle went on, followed by Messerschmitt fighters.

- Due to the German airfields' closeness to the shore, the aircraft of No. 11 Group sometimes lacked the necessary forewarning to prevent these assaults. Park's fighters were forced to perform patrols as a result, placing a burden on their pilots and machinery. Both sides used the combat over the Channel as a training ground as they got ready for the greater conflict that was to come. Fighter Command downed 227 aircraft while losing 96 during June and July.

Adlerangriff

- Göring was further persuaded that Fighter Command was in operation with between 300 and 400 aircraft by the sparse numbers of British fighters his aircraft had met in July and early August. He was preparing for a big aerial assault known as Adlerangriff (Eagle Attack), and he was looking for four straight days of clear skies to launch it. On 12 August, some early strikes were launched, during which German aircraft attacked four radar installations and lightly damaged several coastal airfields.

- The strikes caused little long-term damage since they were aimed at the radar towers rather than the more crucial plotting huts and operations centers. The radar plotters from the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) demonstrated their tenacity throughout the bombing by continuing to work when bombs burst close by. British forces lost 22 of their soldiers while taking down 31 Germans.

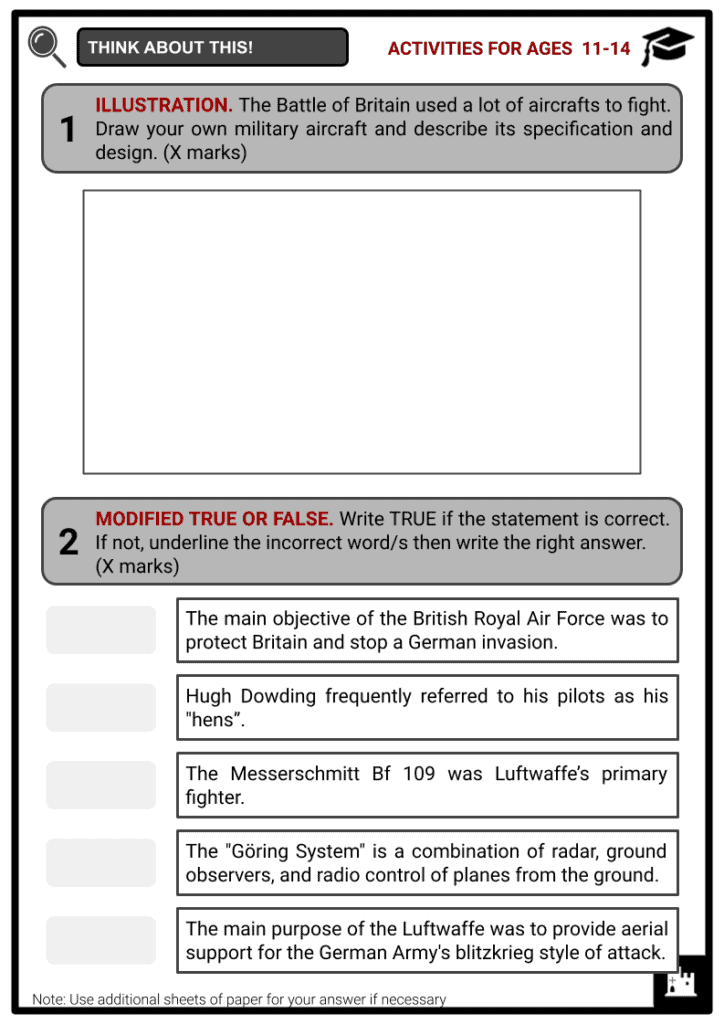

Air Battle in 1940 - German forces, who believed they had done major damage on 12 August, started their onslaught the next day, known as Adler Tag (Eagle Day). Due to unclear orders, a series of jumbled strikes were carried out in the morning, followed by bigger raids that struck a range of targets around southern Britain in the afternoon but did not cause any permanent harm. The following day, Fighter Command fought the raids with squadron strength. The Germans prepared their biggest assault to date for 15 August, with Luftflotte 5 assaulting northern British sites and Kesselring and Sperrle striking the south. This strategy was predicated on the mistaken idea that No. 12 Group had been feeding reinforcements south during the prior days and could be prevented from doing so by striking the Midlands.

- Luftflotte 5's aircraft were detected far out at sea and were unescorted.

- No. 13 Group attacked but suffered severe casualties and made little progress.

- Luftflotte 5 had no further involvement in the conflict.

- RAF airfields in the south were severely damaged.

- Park's soldiers, assisted by the No. 12 Group, fought in sortie after sortie.

- RAF Croydon was accidentally hit by a German aircraft during combat, killing over 70 people and angering Hitler.

- Fighter Command shot down 75 Germans and lost 34 aircraft and 18 pilots.

- The next day, despite bad weather, German raids continued.

- On 18 August, both sides suffered their greatest losses in the conflict.

- The 18th, known as the "Hardest Day," saw raids on sector airfields at Biggin Hill and Kenley.

- The damage was transitory, and business was not significantly impacted.

CHANGE IN APPROACH

- After the strikes on 18 August, it became obvious that Göring's pledge to Hitler to swiftly destroy the RAF would not be kept. Operation Sea Lion was consequently put off until 17 September. The Ju 87 Stuka was also removed from the conflict, and the Bf 110's role was diminished as a result of the significant casualties sustained on the 18th. Future operations were to target Fighter Command facilities and airfields exclusively, leaving the radar sites out of the picture. German fighters were also instructed to closely accompany the bombers rather than perform sweeps.

- During the Battle of Britain, a disagreement arose between Air Vice Marshal Keith Park and Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory over the best strategy to employ. Leigh-Mallory supported large, organised assaults with "Big Wings" made up of multiple squadrons, while Park preferred intercepting enemy raids with individual squadrons.

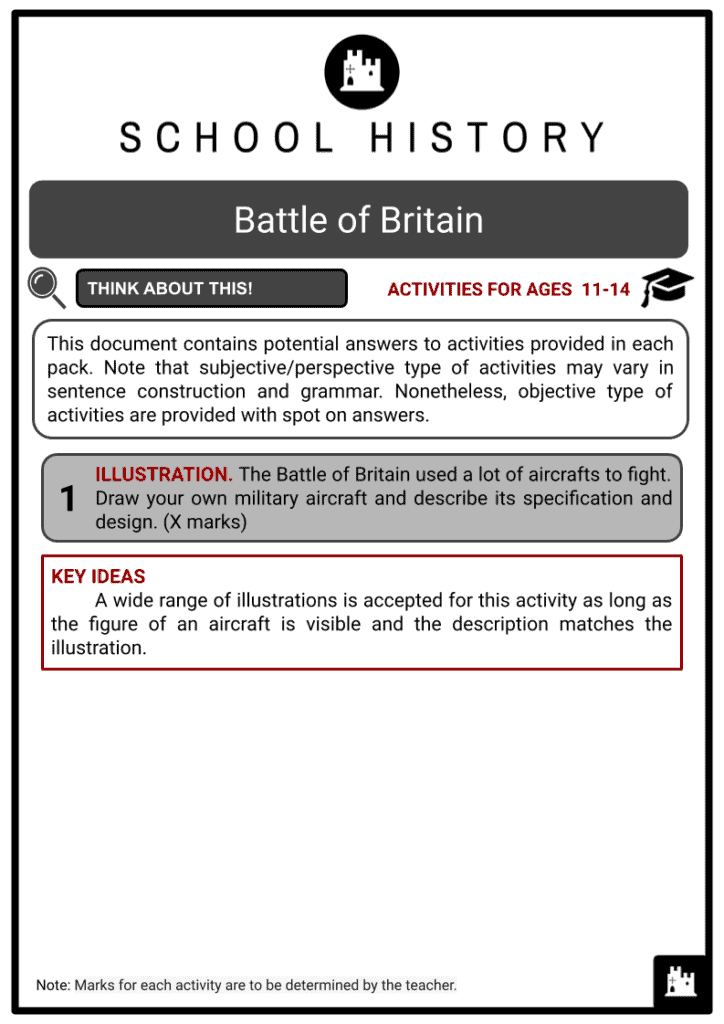

RAF and Luftwaffe Bases - The Big Wing strategy aimed to reduce RAF fatalities and increase enemy losses but took longer to form and increased the risk of aircraft being grounded for refueling. Despite support for both strategies from the Air Ministry and Dowding's commanders, personal conflicts between Park and Leigh-Mallory worsened the issue, and a resolution was not reached.

- The German bombing campaign started with attacks on British factories and airfields on 23 and 24 August, with parts of London's East End hit on 24 August. The RAF retaliated by attacking Berlin on 25 and 26 August. The pressure on Park's group increased as Kesselring's planes carried out 24 strong attacks on their airfields. The shortage of pilots was addressed through transfers from other branches of the military and the activation of foreign (Polish, French, and Czech) squadrons, along with individual pilots from the US and Commonwealth.

- When the fight was at its most crucial point, Park's soldiers battled to keep their fields in use as losses in the air and on the ground grew. On the first day of the conflict, on 1 September, British losses topped German losses. Early in September, German bombers also started launching attacks against London and other places in retaliation for their ongoing strikes on Berlin. Göring started organising daily attacks on London on 3 September. The Germans made every attempt to remove Fighter Command from the skies over southeast England, but they were unsuccessful. Although Park's airfields were still operational, some believed that the No. 11 Group may be forced to retreat after another two weeks of such strikes because of an overestimation of German power.

- Hitler gave the order to attack London and other British towns on 5 September.

- The Luftwaffe changed its strategy from attacking airfields to cities.

- Fighter Command was able to recover and prepare for the upcoming assault due to the pause in attacks.

- On 7 September, nearly 400 bombers targeted the East End.

- No. 12 Group's "Big Wing" missed the battle due to difficulties forming.

- On 15 September, the Luftwaffe launched a large-scale attack but suffered significant casualties and was defeated.

- Hitler postponed Operation Sea Lion on 17 September due to the Luftwaffe's losses.

- Goering directed a shift to nighttime bombing after the daytime bombing was ineffective.

- The daytime bombing stopped in October, but the worst of the Blitz started later that fall.

AFTERMATH

- The Battle of Britain, which took place between July and October 1940, was a turning point in World War II. Germany had planned to invade Britain, but the invasion danger was avoided when the assaults ceased and fall storms began to batter the English Channel. The British victory in the battle gave the Allies a lift in morale and influenced public opinion across the world to support their cause. The British lost 1,547 aircraft in the conflict, along with 544 people. 2,698 people were killed and 1,887 planes were lost by the Luftwaffe.

- Vice Marshal William Sholto Douglas and Leigh-Mallory accused Dowding, the commander of Fighter Command, of being overly cautious during the conflict. Both men believed that raids should be stopped by Fighter Command before they reached Britain. This strategy was rejected by Dowding because he thought it would result in more aircrew losses. Even though Dowding's strategy and tactics were successful in winning the battle, his superiors came to view him as tough and recalcitrant. In November 1940, not long after winning the conflict, Dowding was fired from Fighter Command and replaced by Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal. Park was also fired and relocated because he was an associate of Dowding.

- Historians generally agree that the Luftwaffe was unable to destroy the RAF.

- According to Stephen Bungay, Dowding and Park's approach of deciding when to confront the opposition while yet keeping a cohesive force was validated.

- The Germans conducted several spectacular strikes against significant British businesses, but they could not destroy the British economic capacity, and made little systematic attempt to do so.

- The fact that the threat to Fighter Command was extremely genuine cannot be hidden in hindsight, and the participants felt that there was only a small window of opportunity between success and failure.

- But, even if the German assaults on the 11 Group airfields had persisted, the RAF still had the option of withdrawing to the Midlands, out of the reach of German fighters, and carrying on the fight from there.

- With the culmination of the concentrated daylight raids, Britain was able to rebuild its military forces and establish itself as an Allied stronghold, later serving as a base from which the liberation of Europe was launched. The victory was as much psychological as physical. Winston Churchill summed up the work of Dowding's "chicks" in a speech to the House of Commons during the height of the war by remarking, "Never in the sphere of human strife was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Britain#/media/File:Pilots_of_No._32_Squadron_at_Hawkinge_during_the_Battle_of_Britain.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-2007-0316-500,_Adolf_Hitler_und_Hermann_G%C3%B6ring.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adlertag#/media/File:British_and_German_aircraft_a_dog_fight.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Britain#/media/File:Battle_of_Britain_map.sv