Bloody Sunday 1972 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Bloody Sunday 1972 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background: The Troubles

- Prelude to the March

- Events of Bloody Sunday

- Aftermath

- Saville Inquiry

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Bloody Sunday 1972!

On 30 January 1972, 26 unarmed citizens were shot by British soldiers during a protest march in Northern Ireland. The day is known as Bloody Sunday. For a long time, the government claimed that the soldiers were acting in self-defence, but an investigation found that this was not the case. Many individuals died: 13 were murdered outright, while another man died four months later due to his injuries. Many victims were shot while escaping the military, and others were shot while attempting to aid the injured.

BACKGROUND: The Troubles

- Many Irish Nationalists and Catholics in Northern Ireland saw Derry City as the epitome of ‘fifty years of Unionist misrule’. Despite having a nationalist majority, gerrymandering ensured that elections to the City Corporation always returned a unionist majority. The city was believed to be starved of public investment: highways were not extended to it, a university was established in the smaller Protestant-majority town of Coleraine rather than Derry and, most importantly, the city’s housing stock was in disrepair.

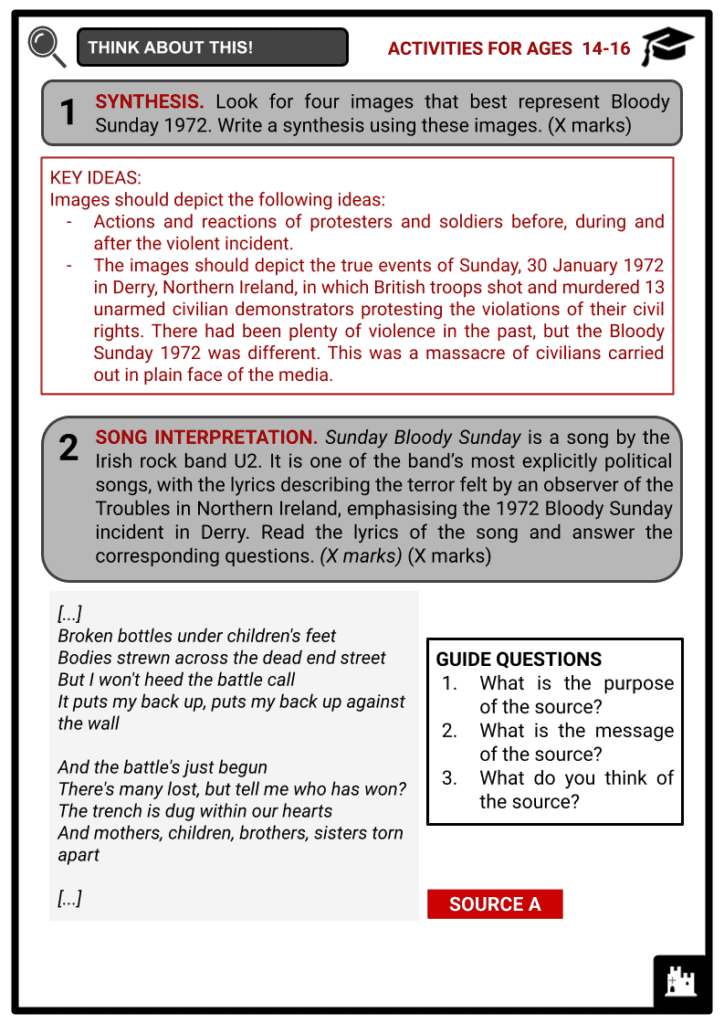

Political map of Ireland - In the late 1960s, Derry became a vital focus of the civil rights campaign spearheaded by organisations like the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). In August 1969, it was the site of the huge riot known as the Battle of the Bogside, which prompted the Northern Ireland administration to request military assistance. While many Catholics welcomed the British Army as a neutral force, as opposed to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), considered a sectarian police force, relations between the two quickly worsened.

- Internment without trial was implemented on 9 August 1971 in response to growing levels of violence throughout Northern Ireland. Following the implementation of detention, there was widespread unrest in the region, with 21 people dead in three days of violence. In what became known as the Ballymurphy Massacre, troops from the Parachute Regiment shot and killed 11 people in Belfast. Bombardier Paul Challoner was shot by a sniper in the Creggan housing complex on 10 August, becoming the first soldier killed by the Irish Republican paramilitary force known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA) in Derry.

Notable IRA actions within the brigade’s operational area in Derry

1971

- Two British soldiers, David Tilbury (29) and Angus Stevens (18), were murdered in an IRA bomb strike on an observation post at the rear of the Rosemount RUC/British Army camp in Derry on 27 October 1971.

1972

- On 7 July 1972, two British Army captains were apprehended and detained by an IRA patrol in Derry’s Bogside district while off duty. The two officers were grilled for 18 hours before being released unharmed.

PRELUDE TO THE MARCH

- Northern Ireland Prime Minister Brian Faulkner prohibited all regional parades and marches until the end of the year on 18 January 1972. An anti-internment march was conducted at Magilligan strand near Derry four days later in violation of the restriction. Protesters marched to a detention camp but were met with resistance from Parachute Regiment soldiers. When some demonstrators flung stones and attempted to go around the barbed wire, paratroopers forced them back with close-range rubber bullets and baton charges.

- The paratroopers severely beat several demonstrators, who had to be physically stopped by their own officers. These charges of paratrooper cruelty were widely publicised on television and in the press. Some members of the British Army believed the paratroopers had used excessive force. On 30 January, NICRA planned another anti-internment march in Derry. To avoid riots, the authorities agreed to allow it to progress through the Bogside but to prevent it from reaching Guildhall Square. Major General Robert Ford, then Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, directed that the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment (1 Para), be sent to Derry to arrest protesters. Operation Forecast was the code name for the arrest operation.

EVENTS OF BLOODY SUNDAY

- The march gathered on the Creggan while chanting on the beautiful afternoon of 30 January. It made its way down to the Bogside, led by the coal lorry, its numbers growing as more people joined along the way. When the lorry reached the intersection of William Street and Little James Street, it swerved south along the latter and went towards Free Derry Corner. Despite stewards’ efforts to direct marchers to follow the lorry, a considerable number continued along William Street towards Barrier 14, just before the intersection of Chamberlain Street.

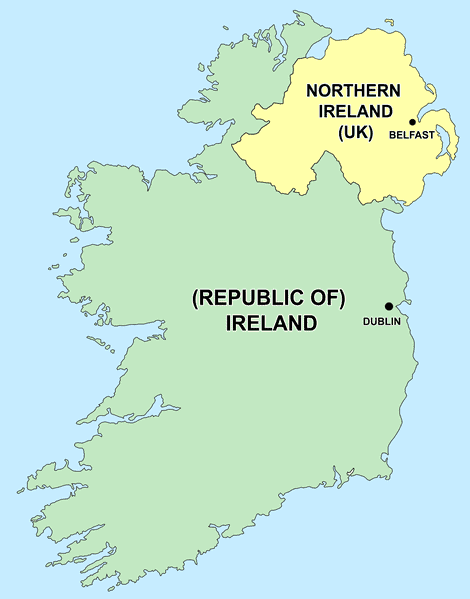

Map showing the places where the violent shooting during Bloody Sunday took place

3.55 PM

- Soldiers opened fire on Damien Donaghy and John Johnston in a decrepit building on William Street, away from the melee and out of sight of the gathering. Both were treated for their injuries and sent to the hospital.

- Around the same time, as the violence on William Street was dissolving, paratroopers asked permission to commence an arrest operation. By 4.05 pm, most people had made their way to Free Derry Corner to attend the meeting.

4.07 PM

- A 1 Para section was ordered to enter William Street to commence an arrest operation targeting any lingering protestors. The order authorising the arrest operation stipulated that the soldiers were ‘not to conduct a running battle down Rossville Street’.

4.10 PM

- Soldiers from the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment’s Support Company opened fire on people in the Rossville Street Flats neighbourhood at 4.10 pm.

4.40 PM

- The violence concluded around 4.40pm, with 13 individuals killed outright and 14 more injured from gunshots. The shooting occurred in four locations: the Rossville Flats car park (courtyard); the forecourt of the Rossville Flats (between the flats and Joseph Place); the rubble and wire barricade on Rossville Street (between the flats and Glenfada Park); and the area surrounding Glenfada Park (between Glenfada Park and Abbey Park).

AFTERMATH

- Aside from the soldiers, all eyewitnesses there, including marchers, residents and the British and Irish media, maintain that the soldiers fired into an unarmed crowd or aimed at fleeing civilians and those assisting the injured. No British soldiers were injured by gunfire or explosions, and no bullets or nail bombs were recovered to support their assertions. The British Army’s version of events was that paratroopers fired back at gunmen and bomb-throwers, as laid out in the House of Commons the day after Bloody Sunday by the Ministry of Defence and confirmed by Reginald Maudling, the Home Secretary at that time.

Monday, 31 January 1972

- Reginald Maudling told the House of Commons about the events of Bloody Sunday, saying, ‘The Army returned the fire directed at them with aimed shots and inflicted several casualties on those who were attacking them with firearms and bombs.’ Maudling then announced an investigation of the march’s conditions.

Tuesday, 1 February 1972

- The nomination of Lord Widgery, then Lord Chief Justice, to conduct an enquiry into the 13 deaths on Bloody Sunday was announced by Edward Heath, then British Prime Minister. The people of Derry responded to this choice of candidate with cynicism and a lack of confidence in his ability to be objective. Indeed, a number of organisations in Derry first opposed participation in the tribunal, but many were later convinced to testify before the inquiry. According to Heath, ‘We must also recognise that the IRA is waging war, not only of bullets and bombs but of words... If the IRA is allowed to win this war, I shudder to think about the future of the people living in Northern Ireland.’

Wednesday, 2 February 1972

- Over 90% of workers in Dublin stopped working in memory of those who had perished, and around 100,000 people marched to the British Embassy. They were carrying 13 coffins as well as black flags. Later, a mob stormed the Embassy with stones and bottles, then with petrol bombs, and the building was set on fire.

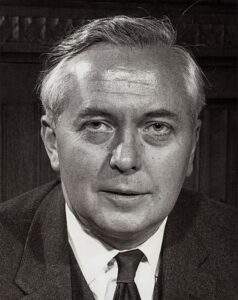

Harold Wilson - Harold Wilson, the opposition leader in the House of Commons at the time, restated his belief that a united Ireland was the only feasible solution to Northern Ireland’s Troubles. Stormont Home Affairs Minister William Craig proposed ceding the west bank of Derry to the Republic of Ireland. The Official IRA attempted to avenge Bloody Sunday on 22 February 1972 by detonating a car bomb at Aldershot military barracks, headquarters of the 16th Parachute Brigade, killing seven ancillary employees.

- Several months after Bloody Sunday, 1 Para, a military unit, once again under the command of Lt Col Wilford, was involved in another contentious shooting incident. On 7 September, paratroopers raided the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) headquarters and several homes in Belfast’s Shankill neighbourhood. UDA was an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. Two Protestant citizens were killed, and several were injured by paratroopers who claimed to be retaliating against loyalist gunmen. The Ulster Defence Regiment of the British Army refused to execute their responsibilities until 1 Para was removed from the Shankill.

SAVILLE INQUIRY

- Prime Minister Blair decided to convene a public inquiry into Bloody Sunday in 1998, near the end of the Northern Ireland peace process. Lord Saville chaired the investigation, which began in April 1998. The other judges were former High Court of Australia Justice John Toohey, who worked on Aboriginal issues, and William Hoyt, former Chief Justice of New Brunswick and member of the Canadian Judicial Council.

Murder Investigation on Bloody Sunday 1972

- The inquest concluded that an Official IRA sniper stationed in a block of flats shot one round towards British soldiers stationed at the Presbyterian church on the other side of William Street. The bullet grazed a drainpipe instead of the soldiers. According to the investigation, it was fired immediately after British forces shot Damien Donaghey and John Johnston in this location. It dismissed the sniper’s claim that he fired in retaliation, noting that he and another Official IRA member were already in position and most likely fired because the chance presented itself.

- Following the publication of the Saville Report, the Police Service of Northern Ireland’s Legacy Inquiry Branch launched a murder inquiry. On 10 November 2015, a 66-year-old former Parachute Regiment member was arrested for interrogation concerning the deaths of William Nash, Michael McDaid and John Young. Soon after, he was released on bail. The Northern Ireland Public Prosecution Service said in March 2019 that there was enough evidence to charge ‘Soldier F’ with the murders of William McKinney and James Wray, both of whom were shot in the back. In addition, he was accused of four attempted murders.

Impact on Northern Ireland divisions

- Following Bloody Sunday, many Catholics turned against the British Army, viewing it as an enemy rather than a protector. Young nationalists were increasingly drawn to armed republican organisations. With the Official Sinn Féin and Official IRA moving away from mainstream Irish republicanism and towards Marxism, the Provisional IRA began to gain support from increasingly radicalised and disaffected young.

- Two decades after the incident, the Provisional IRA and other minor republican groups, such as the Irish National Liberation Army, intensified their military campaigns against the state and anyone perceived to be in its service. The military campaigns claimed the lives of hundreds of people, with rival paramilitary formations emerging in republican and loyalist communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was Bloody Sunday in 1972?

Bloody Sunday is a tragic 30 January 1972 incident in Derry (Londonderry), Northern Ireland. British soldiers fired on unarmed civil rights protesters, resulting in the deaths of 13 people. Another person died later due to injuries sustained that day.

- What happened on Bloody Sunday?

On that day, a peaceful march was organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association to protest against internment without trial, a policy used by the British government. In an attempt to control the situation, British soldiers opened fire on the protesters. This led to the deaths and injuries of many.

- How many people were killed and injured during Bloody Sunday?

Thirteen people were killed on the day, and another died later due to injuries, bringing the total death toll to 14. Many others were wounded, some seriously.