Bloody Sunday 1905 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Bloody Sunday 1905 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- Putilov Incident

- Events of the Russian Bloody Sunday

- The Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Bloody Sunday 1905!

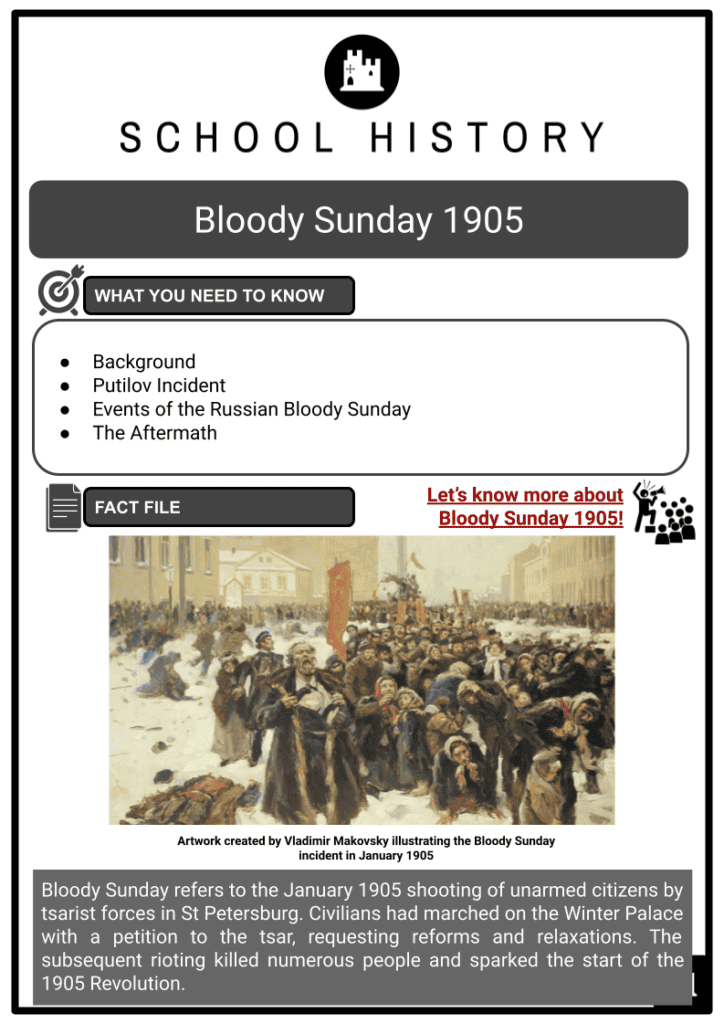

Bloody Sunday refers to the January 1905 shooting of unarmed citizens by tsarist forces in St Petersburg. Civilians had marched on the Winter Palace with a petition to the tsar, requesting reforms and relaxations. The subsequent rioting killed numerous people and sparked the start of the 1905 Revolution.

Background

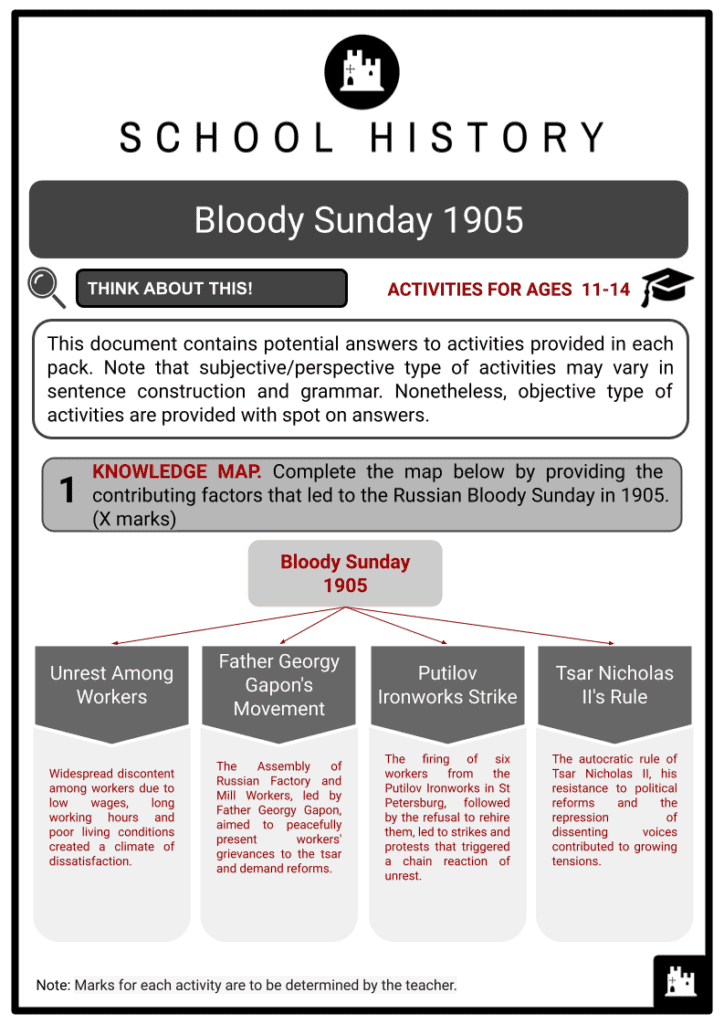

- After the emancipation of serfs by Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1861, a new working class emerged in the industrialising cities of Russia.

- Prior to emancipation, it was impossible to establish a working-class because serfs supplementing their incomes in the cities maintained ties to the land and their landlords.

- Even though the working conditions in the cities were terrible, they were only employed for brief periods and returned to their village when their work was complete or when it was time to resume agricultural labour.

- Serfdom was a form of servitude and debt bondage that existed in Europe during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. It had similarities to and differences from slavery, and it persisted in some countries until the mid-19th century. During the rule of Emperor Alexander II of Russia (1855–1881), he implemented the emancipation reform of 1861, which was the first and most crucial of the liberal changes. This reform successfully eliminated serfdom throughout the Russian Empire.

- The serfs' emancipation led to the formation of a permanent urban working class, which put pressure on the traditional Russian social structure.

- Peasants encountered unfamiliar social dynamics, a strict factory routine, and a challenging life in the city. This recently emerged group of peasant labourers constituted the majority of urban workers.

- Mostly lacking specialised skills, these peasants earned meagre wages, worked in unsafe workplaces, and endured very long working hours, sometimes up to 15 hours a day.

- Peasants under serfdom had little to no interaction with their landowner. However, in the new urban environment, factory employers frequently abused and arbitrarily exercised their power.

- Strikes broke out in Russia as a result of their abuse of power, which was manifested by extended working hours, low pay and a lack of safety measures.

Rising unrest in the cities

- Strikes were seen by Russian law as illegal acts of conspiracy and potential catalysts for rebellion.

- The government, on the other hand, supported the workers' efforts and advocated strikes as an effective instrument that workers might use to help improve their working circumstances.

- Tsarist authorities frequently intervened with heavy punishment, especially for strike leaders and speakers, but often the strikers' allegations were evaluated and found to be justified, and the employers were obliged to address the abuses that the strikers had complained about.

- These changes did not solve a system that was severely unfair and clearly benefited employers. This resulted in the continuation of strikes, including the first significant industrial strike in Russia in St Petersburg in 1870.

- This new phenomenon sparked many additional strikes in Russia, reaching its height between 1884 and 1885 when about 4,000 workers went on strike at Morozov's cotton mill.

- This massive strike prompted officials to consider regulations that would restrict employer abuse and ensure workplace safety. In 1886, a new law was enacted that required factory employers to specify working conditions in writing.

- This included worker treatment, working hours, and safety measures taken by the employer. This new law also established factory inspectors tasked with maintaining industrial harmony. In 1897, the workday was shortened to 11.5 hours as a consequence of the 1890s' resurgence of strike activity.

Putilov Incident

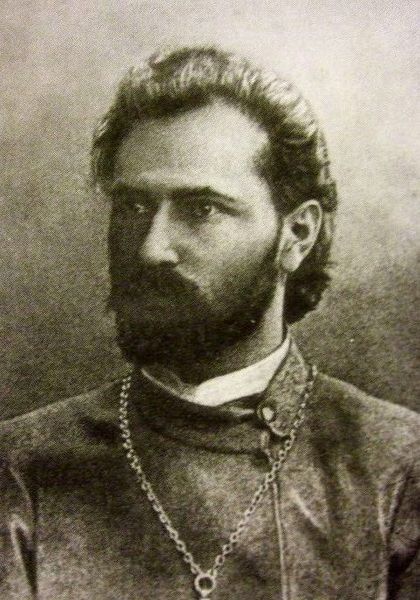

- In order to alleviate economic unrest among workers, Minister of the Interior Plehve formed a legal trade union in St Petersburg. Father Georgy Gapon, a Russian Orthodox priest, led the Assembly of Russian Factory and Mill Workers.

- Fr Gapon was a compelling speaker and efficient organiser who was concerned for Russia's working and lower classes. Fr Gapon had presided over the Assembly since 1903.

- The Assembly was supported by the Department of Police and the St Petersburg Okhrana (secret police). Its goals were to defend workers' rights and raise their moral and religious standing.

- The Assembly functioned as a form of union for the workers in St Petersburg.

- Portrayed as strongly conservative due to its endorsement of autocratic rule, the Assembly aimed to counteract revolutionary influences.

Georgy Apollonovich Gapon - It also aimed to pacify the workers by advocating for improved conditions, shorter hours and higher wages.

- The Assembly played a role in sparking the events that eventually came to be called Bloody Sunday.

- In December 1904, six workers from the Putilov Ironworks in St Petersburg lost their jobs due to their affiliation with the Assembly, even though the plant manager claimed their dismissal was unrelated.

- Following the refusal of the plant manager to rehire these workers, nearly the entire workforce of the Putilov Ironworks went on strike.

- This action led to sympathetic strikes in various areas of the city, resulting in a total of 150,000 workers from 382 factories joining the strike.

- By 21 January 1905, the city had no newspapers, and all public spaces were officially closed.

Drafting the petition and organising the march

- The decision to compile and present a petition was taken during discussions on the evening of 19 January 1905 at the headquarters of Gapon's movement – the Gapon Hall on the Shlisselburg Trakt in Saint Petersburg.

- As authored respectfully by Gapon himself, the petition made explicit the workers' difficulties and viewpoints and requested better working conditions, fairer wages, and a reduction of the working day to eight hours.

- Other demands included the end of the Russo-Japanese War and the implementation of universal suffrage.

- The march on the Winter Palace was not a revolutionary or rebellious gathering, despite the fact that it was carried out against the will of the authorities.

- The workers of St Petersburg desired fair treatment and better working conditions, so they decided to petition the tsar in the hopes that he would act on it.

- Their appeal was worded in subservient terms, and it concluded with a reminder to the Tsar Nicholas II of his commitment to the people of Russia, as well as their determination to go to any length to ensure their requests were met.

- Gapon, who had a rough history with the tsarist authorities, forwarded a copy of the petition to the Minister of the Interior, along with notice of his intention to lead a procession of members of his workers' organisation to the Winter Palace the following Sunday.

- Troops had been stationed around the Winter Palace and at other strategic locations. Despite the wishes of several members of the imperial family to remain in St Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas II left for Tsarskoye Selo on Saturday, 21 January 1905.

- A cabinet meeting that same evening, convened without any feeling of urgency, concluded that the police would publicise his absence and that the workers would most likely abandon their preparations for a march.

Events of the Russian Bloody Sunday

- Striking workers and their families began gathering at six spots on the industrial outskirts of St Petersburg in the pre-dawn winter darkness of Sunday, 22 January 1905.

- A crowd of more than 3,000 marched freely towards the Winter Palace, the official residence of the tsar.

- The fact that Nicholas II wasn't home was unknown to the silent crowd. The total number of people estimated to be involved varies greatly, with police estimates of 3,000 and organiser claims of 50,000.

- It was originally planned for women, children and old workers to lead the march in order to emphasise the unity of the movement.

- Vera Karelina, a Russian labour activist and a member of Gapon's inner circle, had encouraged women to participate despite the fact that she expected casualties. In retrospect, younger men moved to the front to form the leading ranks.

- Significant armed forces were stationed in and around the Winter Palace.

- These included forces of the Imperial Guard, which provided the permanent garrison of St Petersburg, as well as Cossacks and infantry regiments brought in by rail from Reval and Pskov.

- The troops, now numbering around 10,000, had been ordered to stop the marching columns before they reached the palace square, but the government forces' reaction was erratic and unclear.

- When the crowd of people continued to press forward, the Cossacks and regular cavalry charged with sabres or trampled on them.

- Large family groups were still strolling along the Nevsky Prospekt (a main street in St Petersburg) as of 2pm, as was typical on Sunday afternoons, most of them oblivious to the extent of the violence elsewhere in the city. Among them were groups of workers still heading to the Winter Palace, just as Gapon had planned.

- A detachment of the Preobrazhensky Guards, who were initially stationed in Palace Square with around 2,300 soldiers in reserve, moved onto Nevsky Prospekt. They lined up opposite the Alexander Gardens.

- After giving a single warning, a bugle sounded, and the soldiers fired four volleys into the panicked crowd, many of whom had not participated in the organised marches.

- The exact count of casualties from the day's confrontations remains uncertain. According to the tsar's officials, 96 individuals were reported dead and 333 injured.

- On the other hand, sources critical of the government asserted a toll exceeding 4,000 fatalities. More balanced approximations tend to settle around 1,000 people either killed or wounded, including those harmed by gunfire or trampling during the chaotic panic.

- Additionally, an alternative source mentioned that the official assessment indicated 132 lives lost.

- As news spread throughout the city, chaos and looting erupted. On the same day, Gapon's Assembly was shut down, and Gapon swiftly departed Russia with the help of writer and political activist Maxim Gorky.

- Despite not being present at the Winter Palace and not issuing the command for the troops to shoot, the tsar was widely held responsible for the poor and insensitive way the crisis had been managed.

The Aftermath

- The immediate outcome of Bloody Sunday was the emergence of a widespread strike movement across the entire country.

- Strikes started happening beyond St Petersburg, in cities like Moscow, Warsaw, Kovno, Vilna, Reval, Tiflis, Riga, Baku and Batum. Altogether, around 414,000 people took part in these work stoppages in January 1905.

- Tsar Nicholas II tried to contain the situation by introducing a duma, but as the strike movement kept spreading, the autocracy eventually resorted to harsh force towards the end of 1905.

- This was an attempt to suppress the growing strike movement.

- From October 1905 to April 1906, approximately 15,000 peasants and workers were either executed by hanging or shot.

- Another 20,000 were wounded, and 45,000 were sent into exile.

- A duma refers to a Russian assembly that serves in an advisory or legislative capacity. The initial officially established state duma was the Imperial State Duma, which Tsar Nicholas II introduced to the Russian Empire in 1905.

- One of the most significant outcomes of Bloody Sunday was the notable shift in how Russian peasants and workers perceived things. In the past, the tsar had been seen as the defender of the people.

- In times of crisis, the masses would turn to the tsar, often through petitions, and the tsar would promise to make things right.

- The lower classes had placed their trust in the tsar, and any difficulties they encountered were usually attributed to the Russian nobles.

- However, after Bloody Sunday, the perception of the tsar changed. He was no longer seen as distinct from the bureaucrats and was held directly accountable for the tragic events.

- This shattered the social agreement between the tsar and the people, undermining the legitimacy of his rule and his divine right to govern.

- While Bloody Sunday wasn't initially intended as a revolutionary act, the consequences of how the government reacted started to plant the seeds of revolution.

- It called into question the idea of autocracy and challenged the tsar's authority.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why was Bloody Sunday in 1905 a turning point for Russia?

Bloody Sunday in 1905 was a turning point for Russia because it triggered widespread protests, leading to the 1905 Revolution. The massacre shattered public trust in the monarchy, fueling organised opposition and demands for political reforms. The Tsar's concession of the October Manifesto marked a departure from autocracy, and the event paved the way for future revolutionary movements, ultimately leading to the downfall of the Romanov dynasty during the 1917 Russian Revolution.

- What led to the events of Bloody Sunday?

The events were precipitated by widespread social unrest and discontent in Russia, driven by factors such as harsh working conditions, low wages, political repression, and calls for political reforms.

- How many people were killed or injured on Bloody Sunday?

The exact number of casualties remains disputed, but estimates suggest that several hundred people were killed or wounded during the massacre.