Download Clara Barton Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Clara Barton to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life of Clara Barton

- Participation in the Civil War

- Founding of the American Red Cross

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Clara Barton!

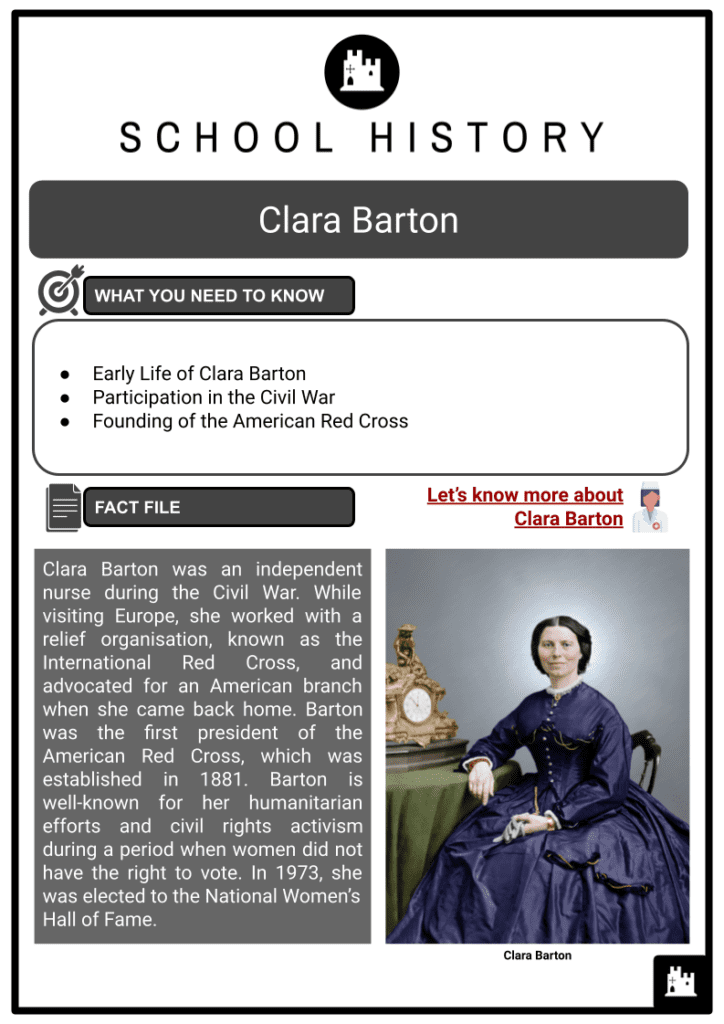

Clara Barton was an independent nurse during the Civil War. While visiting Europe, she worked with a relief organisation, known as the International Red Cross, and advocated for an American branch when she came back home. Barton was the first president of the American Red Cross, which was established in 1881. Barton is well-known for her humanitarian efforts and civil rights activism during a period when women did not have the right to vote. In 1973, she was elected to the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Early Life

- Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born in North Oxford, Massachusetts, on 25 December 1821, and was named after the hero of Samuel Richardson’s novel Clarissa. Her father was Captain Stephen Barton, a member of the local militia and a selectman (political), who instilled patriotism and a broad humanitarian interest in his daughter.

- Barton was sent to school alongside her brother, Stephen when she was three years old. She excelled in reading and spelling. At school, she became good friends with Nancy Fitts, who – due to her extreme shyness – was the only known childhood friend Barton had.

- When Barton was ten years old, she took it upon herself to nurse her brother David back to health after he suffered a terrible head injury after falling off the roof of a barn. She studied how to administer prescribed medication to her brother, as well as how to bleed him with leeches, which was a common treatment at the time. Long after the physicians had given up on David, she remained to look after him. He was able to fully recover.

- Her parents tried to help her overcome her timidity by putting her in Colonel Stones High School, but their plan backfired. Barton became more shy and depressed, and she refused to eat. She was returned to her home to recover her health.

- Barton’s parents urged her to become a schoolteacher in order to help her overcome her shyness. She received her first teacher’s certificate in 1839, when she was just 17 years old. This field caught Barton’s interest and helped motivate her; she went on to run a successful redistricting effort that allowed workers’ children to attend school. This and other successful programmes gave Barton the confidence she needed to seek equal pay for teaching.

- After her mother’s death in 1851, the family home shut. Barton opted to continue her studies by enrolling at the Clinton Liberal Institute in New York to study writing and languages. She made a lot of friends at this institution, and they helped her extend her perspective on a lot of issues that were going on at the time.

- Barton observed the lack of public schools in Bordentown, a nearby community, while teaching in Hightstown. She was hired to open a free school in Bordentown in 1852, which was the state’s first free school. She was successful and within a year she had recruited another woman to assist her in instructing over 600 students.

- She moved to Washington, D.C. in 1855 and began working as a clerk in the US Patent Office; this was the first time a woman had been offered a major clerkship in the federal government at a wage comparable to that of a male. For three years, she was subjected to a barrage of abuse and slander from male clerks. As a result of political opposition to women working in government offices, her position was reduced to that of a copyist, and she was fired in 1858, under James Buchanan’s administration, for her ‘Black Republicanism’.

Participation in the Civil War

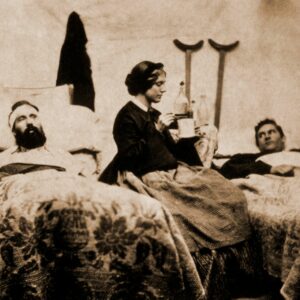

- During the Civil War, Barton did everything she could to assist the soldiers. She began by gathering and distributing supplies for the Union Army. Not content watching from the sidelines, Barton served as an independent nurse and first saw combat in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1862. She also looked to troops who had been wounded in Antietam. For her work, Barton was dubbed ‘the angel of the battlefield’.

-

Barton in the Civil War The Baltimore Riot, which took place on 19 April 1861, was the first major violence of the American Civil War. The Massachusetts regiment’s victims were taken to Washington, D.C, which happened to be Barton’s residence at the time. Wanting to help her nation, Barton rushed to the railway station as the victims arrived, and nursed 40 men.

- Barton immediately recognised them as she had grown up with and even taught some of them. Barton, along with many other ladies, individually provided the sick and injured troops with clothing, food and supplies. She learnt how to store and distribute medical supplies while also providing emotional support to the troops by keeping their spirits up. She would read books to them, send letters to their families on their behalf, converse with them, and encourage them.

- It was on that day that she decided to pursue a career in the army and began collecting medical supplies for Union forces. Quartermaster Daniel Rucker finally gave Barton permission to work on the front lines in August 1862. She was able to enlist the help of others who shared her convictions. Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, in particular, became one of her most avid supporters.

- Union General Benjamin Butler labelled her ‘the lady in charge’ of the hospitals at the front of the Army of the James in 1864. One of the most horrific incidents was when a gunshot ripped through the sleeve of her garment without touching her, killing a guy she was treating. She was dubbed America’s Florence Nightingale.

- Following the end of the American Civil War, Barton discovered that thousands of letters from devastated families to the War Department were going unanswered because the soldiers they were asking about were buried in unmarked graves. Many of these troops were just classified as missing. Miss Barton was compelled to do something about the issue, so she approached President Lincoln in the hopes of receiving official permission to respond to these unanswered questions. Once she was granted permission, the ‘Search for the Missing Men’ began.

Founding of the American Red Cross

- Barton was introduced to the Red Cross and Dr Appia during a trip to Geneva, Switzerland in 1869; he later invited her to be the spokesperson for the American branch of the Red Cross and assisted her in finding financial donors for the foundation of the American Red Cross. She was also introduced to Henry Dunant’s book A Memory of Solferino, which advocated for the establishment of national associations that would offer aid on a voluntary and neutral basis.

- She aided the Grand Duchess of Baden in the establishment of military hospitals before the start of the Franco-Prussian Conflict in 1870, and she offered the Red Cross society a lot of help during the war.

- When Barton returned to the United States, she started a campaign to have the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) recognised by the US government. She started working on this initiative in 1873. She spoke with President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878, and he expressed the sentiment of most Americans at the time, that the United States would never again face a disaster like the Civil War.

- Barton was eventually successful during President Chester Arthur’s administration, arguing that the new American Red Cross could respond to calamities other than war, including earthquakes, forest fires and storms.

- Barton became President of the American branch of the society, which held its first formal meeting at her I Street apartment in Washington, D.C. on 21 May 1881. The first local organisation was established in Dansville, Livingston County, New York, where she had a country home, on 22 August 1881.

- With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, the society’s function shifted, and it began assisting refugees and Civil War captives. The appreciative people of Santiago erected a monument in honour of Barton in the town plaza when the Spanish-American War ended, and it still remains today. Barton was praised in various publications in the United States, and she personally reported on Red Cross operations.

- In 1904, Clara Barton resigned from the American Red Cross due to a power struggle inside the organisation and allegations of financial mismanagement. Despite her reputation as an authoritarian leader, she never received a salary for her work at the organisation and occasionally used her wealth to aid rescue operations.

- Clara Barton remained active after leaving the Red Cross, delivering speeches and lectures. She also released a book called The Story of My Childhood in 1907. On 12 April 1912, Barton died at her home in Glen Echo, Maryland.