Corfu Incident Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Corfu Incident to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background of the Incident

- Murder of Tellini

- Attack of Corfu

- Resolution and Conclusion of the Incident

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Corfu Incident!

The Corfu Incident was a military and diplomatic conflict between Greece and Italy in 1923. It began when an Italian general leading a committee to settle a boundary dispute between Greece and Albania, was killed, along with members of his staff, on Greek land. Benito Mussolini responded by giving Greece an order, and when it was not fully complied with, he sent troops to attack and capture Corfu. In defiance of Mussolini, who threatened to leave the League of Nations if it served as an arbitrator in the dispute, the Conference of Ambassadors finally put out a deal that favoured Italy. This was a warning sign of the league's vulnerability in the face of more powerful nations.

BACKGROUND OF THE INCIDENT

- Italy had captured the Greek-dominated Dodecanese Islands during the Italo-Ottoman War of 1911–1912. The Dodecanese Islands, with the exception of Rhodes, would be transferred to Greece under the 1919 Venizelos–Tittoni agreement in exchange for Greek acknowledgement of Italian rights to a portion of Anatolia. Mussolini came under increasing pressure from the Greeks about the Dodecanese Islands. In the summer of 1923, as part of his preparations to legally annexe the islands to Italy, he ordered the Italian garrison there to be strengthened, which prompted Greece to write protest letters.

- Lord Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary, informed Mussolini that Britain would surrender Jubaland and Jarabub to Italy as part of a general agreement of all of Italy's claims in May 1923 while on a trip to Rome.

- He added that Italians had to resolve their differences with both Yugoslavia and Greece as a component of the cost of Jubaland and Jarabub.

- Jubaland and Jarabub were pledged to Italy as part of the conditions of the Treaty of London of 1915, which allowed Italy to enter World War I.

Benito Mussolini - Although Britain had agreed in the Milner-Scialoja agreement in 1920 to hand over Jubaland and Jarabub to Italy, the British had later constrained that to the Italians resolving the Dodecanese Islands conflict first. Mussolini's reputation suffered greatly as a result of the Allied powers abandoning their assertions to Turkey under the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923.

- As the leader of the opposition, Mussolini had pledged to win all of the territories the Italians had fought for in World War I, including a sizable portion of Anatolia.

- He had previously criticised his predecessors as incompetent politicians who had brought about the 'mutilated victory' of 1918 and guaranteed that he would be a 'strong leader' who would undo it.

- Between Greece and Albania, there existed a border dispute. The two states brought their disagreement to the Conference of Ambassadors, which established a panel made up of British, French and Italian officials to decide the boundary. The League of Nations gave this body permission to resolve the conflict. Enrico Tellini, a general from Italy, was named the commission's chairman. The communication between Greece and the commission was strained from the beginning of the discussions. Finally, the Greek representative came out and accused Tellini of supporting Albania's allegations.

MURDER OF TELLINI

- At the Kakavia border crossing, close to the town of Ioannina in Greek territory on 27 August 1923, Tellini, Major Luigi Corti, Lieutenant Mario Bonacini, Albanian interpreter Thanas Gheziri, and the chauffeur Remigio Farnetti were ambushed and killed by unidentified assailants. Due to its proximity to the line of contention, the event may have been committed by either side.

- Newspapers in Italy and the Albanian government's official statement claimed that the Greeks were responsible for the attack, while other sources, including the Greek government, its authorities, and the Romanian consul in Ioannina, blamed Albanian bandits for the murder. According to British Ambassador to Greece Reginald Leeper's letter to British Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden from April 1945, the Cham Albanians killed General Tellini. The letter claimed that General Tellini and the other officers were murdered by Cham Albanian bandit Daout Hodja (also known as Daout Hoxha).

- Following the murder, anti-Greek protests started to occur throughout Italy. According to Australian publications, all Greek newspapers condemned the Tellini crime and expressed positive feelings towards Italy. They anticipated that the Cabinet would provide Italy with justifiable satisfaction while remaining within the bounds of national honour.

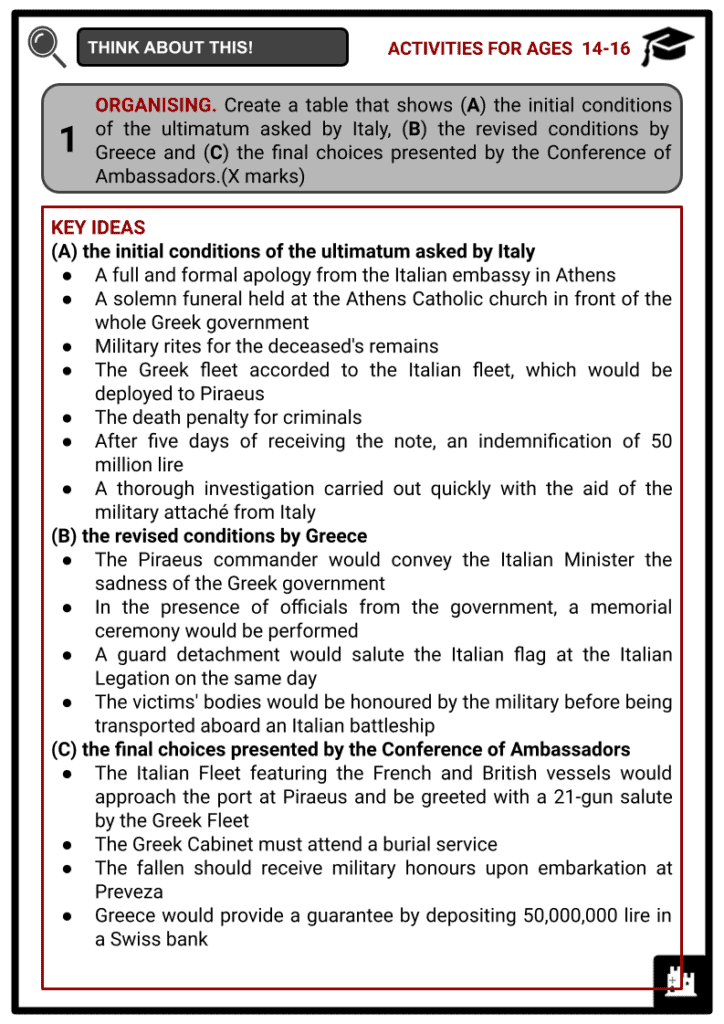

- On 29 August 1923, Italy issued an ultimatum to Greece, requesting:

- A full and formal apology from the Italian embassy in Athens

- A solemn funeral held at the Athens Catholic church in front of the whole Greek government

- Military rites for the deceased's remains

- The Greek fleet accorded to the Italian fleet, which would be deployed to Piraeus

- The death penalty for criminals

- After five days of receiving the note, an indemnification of 50 million lire

- A thorough investigation, carried out quickly with the aid of the military attaché from Italy

- Greece was also required to respond to the ultimatum within 24 hours

- On 30 August 1923, Greece sent Italy a reply, accepting four of the conditions with the following modifications:

- The Piraeus commander would convey the Italian Minister the sadness of the Greek government

- In the presence of officials from the government, a memorial ceremony would be performed

- A guard detachment would salute the Italian flag at the Italian Legation on the same day

- The victims' bodies would be honoured by the military before being transported aboard an Italian battleship

- The other requests were turned down since they would violate Greece's sovereignty and honour. The Greek government also stated that it would be more than happy to accept any assistance Colonel Perone (the Italian military attaché) may be able to lend by providing any information likely to facilitate the discovery of the assassins.

Enrico Tellini - The Greek government further stated that it would be more than willing to grant an equitable indemnity to the families of the victims as a measure of justice and that it did not accept an investigation in the presence of the Italian military attaché. Mussolini and his cabinet rejected the Greek government's response because they were dissatisfied with it. Mussolini's demands were supported by the Italian press, including the opposition newspapers, which stressed that Greece must comply immediately. The choice made by Mussolini was enthusiastically embraced across Italy.

ATTACK OF CORFU

- A crew of the Italian Navy attacked the Greek island of Corfu on 31 August 1923, and between 5,000 and 10,000 soldiers were landed. Aircraft supported the strike. The attack lasted between 15 and 30 minutes. According to other estimates, 20 people were murdered and 32 were injured as a result of the shelling, which also left 16 civilians dead, 30 injured, and two with severed limbs. None of the victims, who were all orphans and refugees, were identified as troops. Children made up the majority of those who died. The Italian bombing was called 'inhuman and repulsive, unjustified and needless' by the commissioner of the British charity Save the Children Fund.

- The Italians imprisoned Greek officers and officials as well as the prefect of Corfu, Petros Evripaios, onboard an Italian cruiser. The 150-man Greek garrison retreated to the interior of the island rather than surrendering. The Italian officers were glad to learn that there were no British people among the victims since they had worried that British nationals would have been hurt or murdered after the landing. However, Italian forces ransacked the home of the British officer who oversaw the police academy.

- Contarini emerged during the crisis as a moderate force within the Italian government, working tirelessly to convince Mussolini to back down and accept a compromise along with Antonio Salandra, the Italian representative to the League of Nations, and Romano Avezzana, the Italian ambassador to France.

- Mussolini, who only took office as prime minister on 28 October 1922, was committed to establishing his authority by demonstrating that he was an atypical leader who did not adhere to the conventional rules of diplomacy.

- The Corfu crisis marked the first confrontation between Mussolini and the traditional Italian elites, who, while they did not object to Il Duce's rash behaviour, disliked his imperialistic policies. Italy and Britain were negotiating at the time for the surrender of Jarabub in North Africa and Jubaland in East Africa to the Italian dominion.

- According to the Palazzo Chigi, presenting Italy to Britain as a trustworthy partner was crucial to the outcome of these talks since Britain was concerned by Mussolini's impulsive actions, including the takeover of Corfu.

- Following the event, martial law was imposed across Greece by the Greek government. To avoid coming into touch with the Italian force, the Greek fleet was instructed to withdraw to the Gulf of Volos. A poignant memorial ceremony for those murdered in the Corfu bombing was performed at the Athens Cathedral, and bells from every church were rung nonstop. Following the service, anti-Italy protests started. All entertainment facilities were closed in remembrance of the bombing victims.

- Following the Italian Minister's objection, the Greek government prohibited the daily Eleftheros Typos for one day and fired the censor for allowing the article that referred to the Italians as 'the fugitives of Caporetto' to run. The Italian Legation in Athens was guarded by a contingent of 30 troops from the Greek government. Greece's newspapers all expressed their disapproval of Italy's conduct.

- Greek ships were barred from the Straits of Otranto by Italy. Greek steamers were imprisoned in Italian ports, and one was captured by a submarine in the Corfu Straits, but on 2 September, the Italian Ministry of Marine ordered the release of all Greek vessels from Italian ports. Demonstrations against Greeks erupted once more in Italy. The Italian government gave the Italian reservists in London instructions to keep themselves in military readiness. Victor Emmanuel III, the King of Italy, left his summer palace immediately and came back to Rome. The Italian legation brought in the military attaché from Italy who had been ordered to look into the assassination of the Italian delegates, and Greek journalists were banished from Italy.

- Albania strengthened its border with Greece and forbade crossing. While some in Turkey counselled Mustafa Kemal to exploit the chance to attack Western Thrace, Serbian publications stated that Serbia would back Greece. The head of Near East Relief deemed the bombardment to be wholly pointless and unjustifiable. Italy contacted the American embassy to voice its disagreement with this assertion.

- Harold Nicolson and Sir William Tyrrell at the Foreign Office also advocated focusing efforts to defend Greece through the League of Nations agency against an aggressor.

- Following Mussolini's threat to quit the league, Lord Curzon abandoned his first attempt to resolve the situation by sending it to the League of Nations.

Mustafa Kemal - Furthermore, if the Corfu event were brought to the league, it was thought that France would block any punishment against Italy since they would need the League Council's permission.

- The Treasury in Whitehall opposed imposing sanctions on Italy on the premises that, since the United States was not a league member, any sanctions imposed by the league would be ineffective because the country would continue to conduct business with Italy, whereas the Admiralty demanded a declaration of war against Italy as a condition for imposing a blockade.

- Kennard favoured fascism over communism, which led him to support appeasement. He claimed that the best way to prevent war was for Britain to put pressure on Greece to accept the Italian demands while attempting to persuade Mussolini to reduce the compensation sums. Further away, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, whose governments both denounced Italy's activities, were more sympathetic to Greece.

RESOLUTION AND CONCLUSION

- Greece made a request to the League of Nations on 1 September, but Italian ambassador Antonio Salandra notified the Council that he was not authorised to handle the problem. Mussolini insisted that the Conference of Ambassadors handle the situation instead of checking with the league. Italy said that it would quit the league rather than allow it to meddle. Britain was in favour of sending the Corfu dispute to the League of Nations, but France was against it because they thought it would set a precedent for the league to become engaged in the French occupation of the Ruhr.

- The issue was brought up in the Conference of Ambassadors because of Mussolini's threat to leave the league and the absence of French support. At the League of Nations, Italy's reputation was preserved, and the French were freed from any ties connecting Corfu and the Ruhr. The parameters on which the disagreement should be resolved were presented by the Conference of Ambassadors to Greece, Italy and the League of Nations on 8 September. The following choices were made:

- The Italian Fleet would approach the port at Piraeus and be greeted with a 21-gun salute by the Greek Fleet, which would also feature French and British vessels.

- The Greek Cabinet must attend a burial service.

- The fallen should receive military honours upon embarkation at Preveza.

- Greece would provide a guarantee by depositing 50,000,000 lire in a Swiss bank.

- The top military official in Greece must apologise to the British, French and Italian ambassadors in Athens.

- The Japanese Lieutenant Colonel Shibuya, a military attaché of the Japanese embassy, would lead a special international commission supervising a Greek investigation into the killings, which must be finished by 27 September.

- Greece was obligated to ensure the commission's safety and cover its costs.

- The conference demanded that the Greek government inform the British, French and Italian delegations in Athens of its full approval promptly, independently and concurrently.

- The conference also asked the Albanian government to make it easier for the commission to work there.

- It was approved on 8 September by Greece and 10 September by Italy. However, the Italians emphasised that they would stay on the island until Greece had fully satisfied them. The decision of the conference was hailed by the Italian press, which also lauded Mussolini. The 50,000,000 lire had been placed in a Swiss bank, according to the Greek representative Nikolaos Politis, who notified the Council on 11 September. On 15 September, the Ambassadors Conference warned Mussolini that Italy had to leave Corfu by 27 September at the latest.

- Before the investigation was complete, on 26 September, the Conference of Ambassadors granted Italy a 50,000,000 lire compensation on the pretext that 'the Greek authorities had been guilty of a certain incompetence before and after the crime'. The Conference of the Ambassadors responded that Italy maintained the right to seek redress from an International Court of Justice in connection with the occupation expenditures after Italy requested 1,000,000 lire per day from Greece for the cost of the possession of Corfu. Greece experienced considerable dejection with the choice because Italy essentially got what she wanted.

- The Italian flag was lowered and the Italian forces left Corfu on 27 September. When the Greek flag was raised, the Italian flagship saluted it, along with the Italian fleet and a Greek destroyer. When the prefect arrived, 40,000 people in Corfu greeted him and carried him to the prefecture. The mob that gathered en masse in front of the Anglo-French consulates raised the British and French flags.

- Until Italy got the 50 million lire, the Italian squadron had to remain moored.

- The Hague Tribunal had access to the 50,000,000 lire that had been put in a Swiss bank, but the bank would not transfer the funds to Rome without permission from the Greek National Bank, which it received that day's evening.

- With the exception of one destroyer, the Italian navy left on 30 September.

- Mussolini's standing in Italy had improved.

- The Municipal Theatre of Corfu hosted several performances of Italian operas throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. This custom was discontinued after the Corfu tragedy. Following the bombardment, the theatre presented Greek operas and theatrical productions by renowned Greek performers including Marika Kotopouli and Pelos Katselis.

- The strategic location of Corfu near the Adriatic Sea's entrance served as the invasion's covert motivation. The crisis was the League of Nations' first significant test, and it failed. It demonstrated the league's weakness and inability to mediate conflicts when a large power challenged a smaller one. Italy, a founder member of the league and a permanent member of the council, had openly disobeyed the authority of the league. In its first significant foreign conflict, the Italian fascist state had succeeded in winning.

- Great Britain's strategy, which throughout the crisis seemed to be the strongest defender of the league, was also a failure during the crisis. The Dodecanese Islands problem was put on hold while the Greeks concentrated on getting Corfu back, and the Greek government stopped objecting to the ongoing Italian occupation of the islands, which Mussolini legally annexed to Italy in 1925. It also demonstrated the intent and tenor of fascist foreign policy. The most aggressive action taken by Mussolini in the 1920s was the Italian invasion of Corfu. Mussolini's standing in Italy had improved.