France in WWII Worksheets

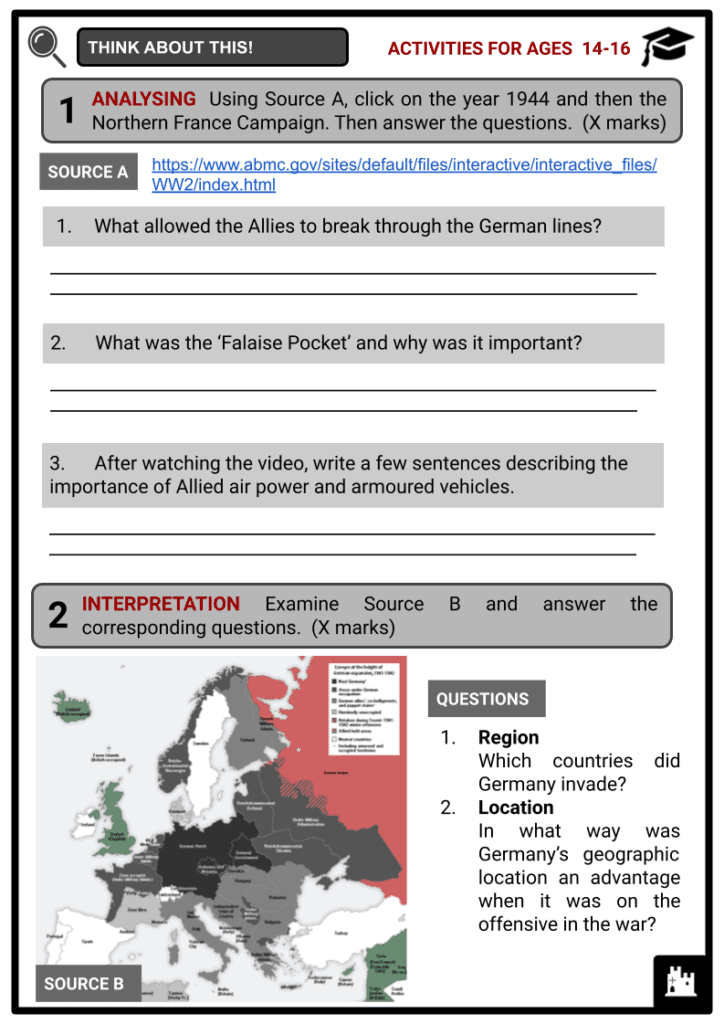

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about France in WWII to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- France Between Wars

- German Invasion

- Occupation and Resistance

- Fall of France

- Liberation of France

- Trials after the Liberation

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about France in WWII!

From 1939 to 1940, the French Third Republic was at war with Nazi Germany. At the Battle of France in 1940, the Germans defeated the French. The Germans occupied French territory in the north and west, and a joint regime led by Philippe Pétain came to power in Vichy. General Charles de Gaulle established a government in exile in London, competing with Vichy France for control of France’s foreign empire, and receiving support from its French allies.

France Between Wars

- German policies differed by country, including direct, brutal occupation and reliance on collaborating regimes. France was divided into two zones: occupied and unoccupied, each with its own set of policies.

- France was one of the more welcoming countries to Jewish immigrants, many of whom came from Eastern Europe, during the interwar period.

- Following World War I, thousands of Jews saw France as a European land of equality and opportunity, and they helped to establish Paris as a thriving centre of Jewish cultural life.

- Exhausted by a large influx of refugees fleeing Nazi Germany and the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, the leaders of the French Third Republic (1870-1940) began to reconsider this ‘open-door’ policy.

- By 1939, French authorities had imposed strict limits on immigration and established a number of internment and detention camps for refugees in southern France, such as Gurs and Rivesaltes.

German Invasion

- There were approximately 350,000 Jews in France when the Third Republic collapsed under German attack in the early summer of 1940. Fewer than half of them were French nationals. Seventy-five thousand Jewish residents lacked French citizenship.

- Many of these people were refugees fleeing Nazi persecution in the Third Reich. Jews and other persecuted people fleeing oppression in German-occupied Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands soon joined them in the summer of 1940.

- On 10 May 1940, German forces invaded France. France signed an armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940, which took effect on 25 June 1940.

- Under the terms of the armistice, Germany annexed the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, which shared borders with Germany and had long been a source of contention between the two countries.

- The German army occupied the rest of northern and western France and administered it alongside occupied Belgium under a military commander (Militärbefehlshaber). General Otto von Stülpnagel held this position from October 1940 to March 1942. General Karl-Heinrich Stülpnagel, his cousin, was appointed Military Commander of Belgium and northern France in March 1942 and held the position until his arrest following the 20 July 1944 assassination attempt on Hitler.

- However, the SS and police had set up shop under von Stülpnagel’s staff in occupied France as early as the winter of 1940-1941.

- SS Colonel Helmut Knochen was the Commander of Security Police and the SD (Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, BdS), and SS Captain Theodor Dannecker represented the Reich Central Office for Security’s Jewish affairs office, which was led by SS Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann.

- Following the replacement of the Military Commander in occupied France and Belgium, and in preparation for the deportation of French Jews, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler appointed SS Major General Carl Oberg as Higher SS and Police Leader (Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer, HSSPF) for German-occupied France in March 1942.

Occupation and Resistance

- Germany invaded and defeated France in just six weeks in the spring of 1940. The entire world was taken aback. How had Europe’s most admired army been brought to its knees so quickly? Many people’s instinctive reaction was to flee in droves to southern France. However, the defeated French government’s response was a one-sided armistice that would leave a psychological scar on the country for decades.

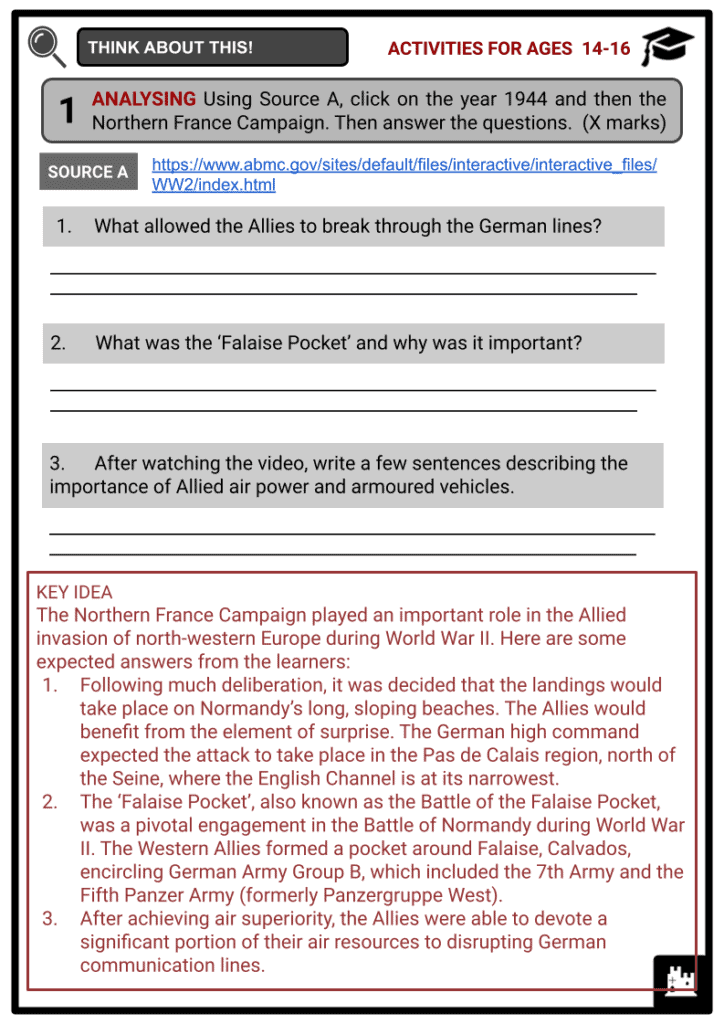

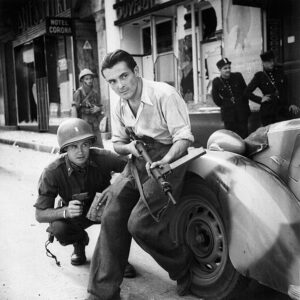

An American officer and a French partisan in 1944 - The armistice, signed by Adolf Hitler and France’s revered leader, Marshal Philippe Pétain, divided the country into two large geographical sectors, one occupied by Germany and one ostensibly designated as free and governed by a new regime in Vichy.

- However, there was a third France, based in England and led by an invincible brigadier general named Charles de Gaulle.

- Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who ruled Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945.

- He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, first as chancellor in 1933 and then as Führer und Reichskanzler in 1934.

- During his dictatorship, he launched World War II in Europe on 1 September 1939, by invading Poland. He was intimately involved in military operations throughout the war and was central to the Holocaust, the genocide of approximately six million Jews and millions of other victims.

- The occupation was not a well-oiled machine. Despite the German Occupation Authority’s internal divisions and shifting policies, one factor remained constant: the Reich required France’s wealth to continue its war against England and, a year later, against the Soviet Union.

- Changes were soon noticeable in French households, which were mostly run by women, because nearly two million men were in POW camps throughout Europe. Essentials like medicine and heating fuel became increasingly scarce.

- The unpredictability of food availability fuelled the growth of a thriving black market. Families would frequently roam the countryside in search of food. Hitler desired a subdued France, but by mid-1942, the nervous occupiers’ imposition of order had become increasingly erratic, and personal safety had become as important a concern as daily needs.

- During the war, the term ‘resistance’ was rarely used. Instead, the French talked about ‘clandestine’ or ‘secret’ activities. The draft of young people as part of the large workforce to support the Reich’s economy was one of the most devastating German demands imposed on the French. Many of the targeted draftees fled to the forests or mountains in order to avoid being recruited as forced labourers. Their involvement in anti-German and anti-Vichy activities was critical in keeping the idea of a free France alive.

Adolf Hitler - At 6pm on 18 June 1940, Charles de Gaulle, a relatively unknown French two-star general, composed himself in front of a microphone at the BBC’s Broadcasting House in London and began a speech. His words, which lasted fewer than six minutes, were an impassioned rejection of the armistice with Nazi Germany announced the day before by Marshal Pétain, the collaborationist Vichy regime’s prime minister and soon-to-be head of state.

- Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 1890 – 9 November 1970) was a French statesman and army officer who led Free France against Nazi Germany during World War II and led the Provisional Government of the French Republic from 1944 to 1946 to restore France’s democracy.

- President René Coty appointed him President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) in 1958, bringing him out of retirement. Following referendum approval, he rewrote France’s Constitution and established the Fifth Republic. Later that year, he was elected President of France, a position he reclaimed in 1965 and held until his resignation in 1969.

- Few French people responded to de Gaulle’s appeal, primarily because it was difficult to reject Pétain’s logic that Nazi Germany had triumphed. Indeed, most saw de Gaulle as irrelevant, preferring to embrace Pétain as the saviour figure, whose authoritarian anti-Semitic regime, based in the central spa town of Vichy, enjoyed widespread support in autumn 1940.

- However, after WWII, de Gaulle’s speech of 18 June 1940 became enshrined in French history as the beginning of the French Resistance, which led directly to the Liberation four years later. This founding narrative enabled the French to forget the humiliation of the Nazi occupation and rebuild national self-esteem.

General Charles reviews Free French Air Forces’ airmen during a Bastille Day parade - In late 1940 and 1941, grassroots groups sprang up across France, independent of de Gaulle and one another. These groups were few in number, and not all of them were military in nature.

Fall of France

- Between 9 May and 22 June 1940, the Battle of France, a remarkable German assault on north-west Europe, resulted in the capture and subjugation of not only France, but also three other countries: Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Belgium. It also witnessed the British Army’s retreat and evacuation from Dunkirk, which was controlled from Dover Castle, and other western French ports. Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Belgium had all fallen, and France was next.

- The German Army moved quickly to launch Case Red. This resulted in German forces striking south into France, with the goal of capturing Paris. It all started on 5 June, with an attack across the Somme and Aisne rivers, heading into north and west central France.

- A separate force from the French side attacked the Maginot Line, the powerful fortifications on France’s eastern border.

- This second attack prevented French troops on the Maginot Line from reinforcing the defenders of Paris against the German attack.

- Despite fierce fighting, the Germans gradually gained the upper hand over the French Army and the remaining British force. The fortresses of the Maginot Line fell one by one, though some held out until July. Meanwhile, the main attacks across the Somme and Aisne, which were initially repulsed by the French, eventually broke through and succeeded in taking Paris on 14 June.

After-bombardment aerial view of Vire, Normandy, 1944. - The French signed an armistice on 22 June, surrendering to the Germans. France had been defeated.

- The Maginot Line, a series of defences built along France’s border with Germany in the 1930s, was intended to prevent an invasion. The 280-mile-long line was built at a cost that may have exceeded $9 billion in today’s dollars, and it included dozens of fortresses, underground bunkers, minefields and gun batteries.

- The Maginot Line was strengthened with reinforced concrete and 55 million tons of steel buried deep underground. It was built to withstand heavy artillery fire, poison gas and whatever else the Germans could attack it with.

- Nonetheless, after WWII, the fortified border that was supposed to be France’s salvation became a symbol of a failed strategy.

- Leaders had focused on countering past-war tactics and technology, failing to prepare for the new threat posed by fast-moving armoured vehicles.

- Instead of being stymied by the Maginot Line, Hitler’s forces sped through a wilderness area in neighbouring Belgium that the French mistakenly thought was impenetrable.

Liberation of France

- The liberation of France began on 6 June 1944, with the Allied landing in Normandy. The French Resistance was crucial in assisting Allied armies in this effort.

- Members of the French Resistance movement came from every economic and political background: conservative nationalists, Catholic and Protestant clergymen, members of the persecuted Jewish community, liberal republicans, and socialist and communist Left activists.

- During the occupation, resistance cells carried out sabotage and guerilla attacks on German and collaborationist authorities, distributed identification papers and documents to Jews and other persecuted people, and maintained escape networks for forced labourers, Allied POWs, Jews and troops trapped behind German lines.

- Resistance groups now aided the Allied advance against German forces. The country was liberated in three months.

- On 25 August 1944, the German forces in Paris surrendered, and General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces (Forces Françaises Libres, or FFL) and President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, marched triumphantly into Paris the following day.

Trials after Liberation

- The provisional government immediately disbanded many collaborationist organisations, including the Milice Francaise (French Militia), the most significant paramilitary group formed to combat the French Resistance movement.

- Following a wave of popular verdicts and summary executions of Vichy officials, the provisional government launched a series of trials against top Vichy officials.

- In October 1945, French Minister of State Pierre Laval under the Petan administration and Joseph Darnand, the leader of the militia, was convicted and executed for treason. On 15 August 1945, Marshall Pétain was sentenced to death for treason. Pétain’s sentence was commuted to life in prison due to his World War I service and his advanced age (he was 89 at the time). He died in 1951.

- Beginning in the mid-1970s, French jurisprudence made efforts to charge several individuals with crimes against humanity for their roles in the Nazi genocide.

- The first successful result of these efforts was the 1987 trial of Klaus Barbie, the ‘Butcher of Lyon’, who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison by a French court, primarily for his role in the deportation and deaths of Jewish refugee children hidden in Izieu.

- Perhaps more significant were the proceedings against three Frenchmen and former Vichy officials involved in anti-Jewish crimes or the implementation of the ‘Final Solution’ in France.

- Rene Bousquet, former Secretary General of the Vichy police, was indicted in Paris in 1991 for negotiating the deportation of 10,000 foreign Jews from the Unoccupied Zone in July 1942 and ordering the notorious round-up of 13,000 Jews at the Vélodrome d’hiver in Paris that same month.

- Christian Didier, a mentally ill man who claimed to have attempted to kill Klaus Barbie, assassinated Bousquet in his Paris home on 8 June 1993, just days before his trial was to begin. These proceedings imply that the legacy of collaboration during ‘les années noires’, or the ‘dark years’ of German occupation, continues to cast a shadow over French politics and culture today.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_France

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Resistance#:~:text=The%20French%20Resistance%20(French%3A%20La,during%20the%20Second%20World%20War.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_Hitler

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_France_during_World_War_II#:~:text=From%201939%20to%201940%2C%20the,P%C3%A9tain%20established%20itself%20in%20Vichy.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombing_of_France_during_World_War_II