Iran–Iraq War Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Iran–Iraq War to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Course of the Iran–Iraq War

- Shi'ite Mobilisation

- New Foreign Policy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Iran–Iraq War!

The Iran–Iraq War started in September 1980 when Iraqi forces invaded neighbouring Iran in hot pursuit. The war, which was sparked by territorial, religious and political conflicts between the two nations, concluded in a ceasefire nearly eight years later, after more than 500,000 troops and civilians had died. Prior to the Islamic Revolution, it was not believed that Iraq could achieve its goal of removing Iran as the dominant force in the Persian Gulf since Pahlavi Iran possessed enormous military and financial power in addition to close ties to the US and Israel.

COURSE OF THE IRAN–IRAQ WAR

- In the 1970s, one persistent source of dispute involved the direct authority of the Shatt al-Arab, the seaport formed by the convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the southern end of which forms the boundary between the two territories. Tensions between Iran and Iraq started almost straight after the formation of Iraq in 1921, as a result of World War I. As part of the 1975 Algiers Agreement, Iran withdrew assistance for a Kurdish rebellion in northern Iraq in exchange for weakened Iraqi sovereignty over the canal.

- The Iranian Revolution of 1978–79 marked a defining moment, overthrowing Shah Mohammad Reza Pallavi's pro-Western administration in favour of a fundamentalist rule led by Shi'ite Muslim cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. In July 1979, Saddam Hussein, then president of Iraq and head of the Ba'ath Party, relied on the backing of his country's minority Sunni Muslims and worried that the Iranian Revolution would spread to Shi'ite-dominated Iraq. In addition, Saddam aimed to revoke the 1975 border accords and retake control of both banks of the Shatt al-Arab, Iraq's only route to the Persian Gulf.

- Saddam made the decision to attack Iran first because of the Iranian military's post-revolutionary weakness. Iraqi soldiers attacked Iranian air bases with airstrikes on 22 September 1980. They then invaded Khuzestan, an oil-producing border area, by land. The invasion was initially successful: by November Iraq had taken control of Khorramshahr and gained further territory.

- However, the Iranian resistance, which was fuelled by the inclusion of revolutionary forces in the conventional armed forces, quickly slowed the Iraqi advance.

Saddam Hussein - Iran began a counteroffensive in 1981, and by early 1982 they had nearly all of the lost territory back.

- Iraq made an effort to find peace before the year's end after pulling back its soldiers to the border areas from before the conflict.

- Iran declined under Khomeini's direction and insisted on escalating the conflict in an effort to remove Saddam's government.

- Iran made its first of several failed incursions into Iraqi territory in July 1982 in an effort to seize control of Basra, the country's port city.

- As Iraq's fortifications hardened in response to Iran's onslaught, the conflict along a front roughly parallel to the border came to a virtual standstill.

- The United States and other Western nations sent battleships to the Persian Gulf to control the output of oil to the global market after both sides conducted air and missile strikes against towns, military installations, oil infrastructure, and shipping.

- Despite having a significant numerical edge over Iran, Iraq possessed more advanced weapons and a better officer corps because of direct backing from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and other Arab governments as well as covert help from Western countries like the United States.

- Khomeini's leadership stayed completely isolated from the world community during the hostage situation involving diplomats at the American Tehran embassy in 1979–81; Iran's primary friends during the war were Syria and Libya. Despite the international community's horror over its use of chemical warfare against Iranian forces and Kurdish people in Iraq who were regarded as being pro-Iran, Iraq continued to pursue peace.

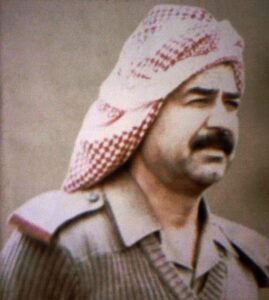

Map of the Gulf War - As a result of Iran's numerous offensive failures over the years, Iraq began its own string of ground assaults in the spring of 1988. Iran's religious authorities were persuaded by Iraqi combat victories that they had a slim chance of winning the war decisively. Under Security Council Resolution 598, which was negotiated by the United Nations, the two countries consented to accept a ceasefire: the conflict legally ended on 20 August 1988.

- The estimated number of casualties in the Iran–Iraq War ranges from one to two million, with half believed to have died, including tens of thousands of Kurds massacred by Iraqi troops. Iraq gained increased power in the area as a result of the war thanks to a reinforced military and the ruthless ambition of its leader, who had received the support of practically all Arab countries in an effort to control Iran. Saddam gave the order to invade Kuwait on 2 August 1990, starting the first Persian Gulf War.

SHI'ITE MOBILISATION

- Iran's recruitment of Iraqi Shi'ite resistance groups was a crucial dynamic throughout the conflict and one that would persist in the decades that followed. Tehran offered backing to various resistance organisations, such as the Kurds, but was primarily concerned with igniting a Shi'ite insurgency campaign inside Iraq, encouraging large-scale military desertions, and attempting to spark an uprising among the country's majority-Shi'ite people.

- Iran's revolutionary passion helped Tehran fight back against an adversary with superior technological capabilities and a large number of supporters, including the United States, its allies in the West, and the Gulf Arab states, but it was unable to elicit a comparable response in Iraq. The opposition organisations and fighters Iran supported were extremely fragmented and without discipline or expertise in combat. They were classified as fundamentalist Shi'ite Islamist terrorists by the world community, and the Baath dictatorship showed an extraordinary capability for repression and coercion, as well as the ability to protect its armed forces from widespread desertions.

- Shi'ites in Iraq failed to rebel against the Baath government like their revolutionary counterparts in Iran.

- Faleh Abdul-Jabar, a late Iraqi sociologist, stated in his book The Shi'ite Movement in Iraq that such resistance organisations failed because they did not fully nationalise their cause.

- Shi'ite Islamist organisations in Iraq were driven into exile and incorporated into the Iranian war effort, looking to audiences at home to be 'internationalist with a national sidetrack'. For Islamic leaders in Iran, the emphasis was on the opposite.

- This, according to Abdul-Jabar, separated Iraq's Shi'ite opposition organisations from the country's mainstream patriotism, which 'formed during the Iraq–Iran conflict and was adopted by the bulk of the Shi'is who opposed Iran'.

- Despite their best efforts, Iran and its Iraqi allies failed to remove the Baath administration. They even recruited and rallied Iraqi military defectors and prisoners of war to form the Badr Brigade militia. Saddam's multifaceted approach to pleasing and reprimanding the Shi'ite community outmatched them. The regime's charm drive included renovating and giving enormous quantities of money to the holy shrine cities. Saddam emphasised Shi'ism's Arab heritage.

- He used Shi'ite iconography throughout the war effort and identified himself as a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali. Imam Ali's birthday was even declared a national holiday in Iraq by Saddam. Indeed, as the conflict with Iran dragged on, Saddam cunningly embraced more Shi'ites.

- In other words, Iran's control over the proxy network it possesses now has taken some time, failure, and harsh lessons. From Tehran's perspective, this has been crucial to preventing Iran's continued existential threat – which was felt strongly during the war 0 from becoming a global problem. While Iran's nuclear aspirations may still be restrained, the war's greatest lasting legacy may be the country's enormous network of armed proxies, which serves as a formidable defensive and deterrent system. The Islamic Republic's capacity to confine, discourage or remove its adversaries on the outside has been greatly aided by this network, which is under the control of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

- Iran created Hezbollah in Lebanon as its sole and most significant foreign legion during the Iran–Iraq War. Since its founding in 1982, Hezbollah has surpassed governmental institutions in Lebanon and attained a supra-state position. It has also grown to be essential to Iran's aspirations of regional expansion and essential to Tehran's capacity to organise, develop and train paramilitary units. Since then, Hezbollah has created its own affiliates in the region, with effects seen in all areas affected by conflicts. In this regard, Hezbollah has outgrown its benefactor.

IRGC - The Badr Brigade presently controls the Interior Ministry and has significant sway over all of Iraq's institutions, making it the most potent paramilitary group in the country. It controls the majority of the 100,000-strong Popular Mobilisation Force and has expanded into Syria to support Bashar Assad's government. During the conflict with Iraq, the group honed its combat skills, capability to find willing combatants, and capacity to overthrow governmental institutions. Hezbollah and the Badr Brigade would not exist without the tragic experiences, lessons and losses of the Iran–Iraq war.

NEW FOREIGN POLICY

- Many of Iran's current decision-makers' perspectives have been influenced by the conflict. Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran's current supreme leader, was Iran's president at the time. Hassan Rouhani, the country's current president, oversaw Iran's air defence at the time. The present IRGC is Iran's most potent military force and an organisation where Khamenei built his name throughout the conflict.

- This includes Qassem Soleimani, the former leader of its special Quds force, who over the last two decades oversaw Iran's extensive network of proxies until his death by the United States in January 2020. More generally, the battle contributed to the perpetuation of the Islamic Republic's founding narrative. The war made it easier for the new authority to solidify its grasp on power following a revolution that was sparked by various political forces.

- Iranian authorities still emphasise how isolated Iran was from the rest of the world after the revolution, left to deal with Iraq's tanks, chemical attacks, and Western and American support for Saddam Hussein on its own. The erroneous 1988 downing of an Iran Air aircraft by the United States, which resulted in the deaths of almost 300 innocent Iranian civilians, strengthened the idea that the Islamic Republic had no allies and that the West was out to bring about Iran's destruction. From Tehran's perspective, this history of exclusion justifies its pursuit of ballistic and nuclear missiles, as well as its continuous use of proxies outside of its borders.

- The establishment of a Shi'ite theocracy in Iran and the eight-year war that followed carved out boundaries for regional stability and peace that still influence regional conflicts today.

- Tehran, for example, gave orders to its agents to carry out the first significant contemporary suicide terrorist acts, such as the bombing of the Iraqi embassy in Beirut in 1981 and the attack on the American Marine bases in Lebanon by Hezbollah.

- The US and French embassies were the targets of suicide terrorist attacks set out in Kuwait in 1983 by members of the Islamic Dawa Party, which ruled Iraq from 2006 to 2018.

- The Islamic Dawa Party was also involved in a number of other high-profile incidents in the area.

- Thus, Shi'ite Islamist organisations and Iranian proxies were among the first to use suicide bombers, which have subsequently been adopted by jihadi movements as a staple method of combat.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran%E2%80%93Iraq_War#/media/File:Capture_in_Khorramshahr.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran%E2%80%93Iraq_War#/media/File:Saddam_Hussein_1982.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran%E2%80%93Iraq_War#/media/File:Map_of_the_frontlines_in_the_Iran-Iraq_War.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ali_Khamenei_with_the_Revolutionary_Guard_Corps_and_Basij_-_Mashhad_(33).jpg