Irish War of Independence Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Irish War of Independence to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Origin and Cause of the Conflict

- Independence Movement

- Declaration of Independence

- Outbreak of the War

- Anglo-Irish Treaty

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Irish War of Independence!

After centuries of British rule, Irish nationalists fought for their country's independence in the Irish War of Independence. Tensions between the two countries escalated with a surge in nationalist sentiment in the early 1900s, and after a series of dramatic uprisings against British control, war was declared in 1919. It resulted in the establishment of the Irish Free State, which eventually evolved into the Republic of Ireland, and Northern Ireland, which remained a part of the United Kingdom.

Origin and Cause of the Conflict

Colonisation in Ireland

- The Norman invasion of Ireland, which took place about 700 years ago, is seen as the beginning of a period in the history of the neighbouring islands of Ireland and England that has been characterised by conflict, brutality and difficult diplomatic relations.

- The Irish Parliament granted King Henry VIII the title King of Ireland in 1541, following an insurrection that challenged royal rule. This act handed the English Crown control over Ireland.

- In 1603, King James VI of Scotland eventually became King James I of England. This brought together two nations that had been at war for centuries.

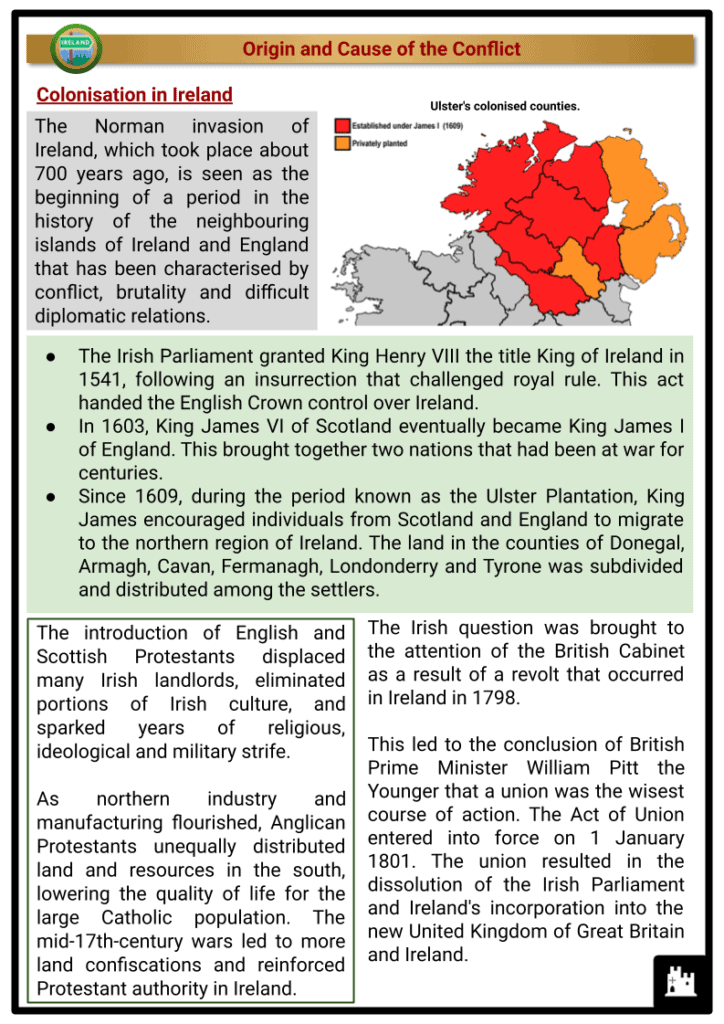

- Since 1609, during the period known as the Ulster Plantation, King James encouraged individuals from Scotland and England to migrate to the northern region of Ireland. The land in the counties of Donegal, Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone was subdivided and distributed among the settlers.

- The introduction of English and Scottish Protestants displaced many Irish landlords, eliminated portions of Irish culture, and sparked years of religious, ideological and military strife.

- As northern industry and manufacturing flourished, Anglican Protestants unequally distributed land and resources in the south, lowering the quality of life for the large Catholic population. The mid-17th-century wars led to more land confiscations and reinforced Protestant authority in Ireland.

- The Irish question was brought to the attention of the British Cabinet as a result of a revolt that occurred in Ireland in 1798.

- This led to the conclusion of British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger that a union was the wisest course of action. The Act of Union entered into force on 1 January 1801. The union resulted in the dissolution of the Irish Parliament and Ireland's incorporation into the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

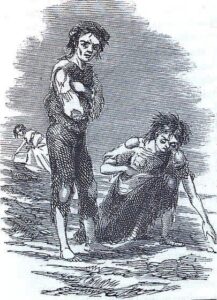

Great Irish Famine

- The subsequent 40 years were relatively peaceful, but the Great Famine of the 1840s planted the seeds of unrest. Many thought that the British government was indifferent, if not neglectful, while the Irish portion of the United Kingdom suffered from crop failure and disease.

Image depicting the Great Famine or Great Hunger - The grave effects of the infestation were exacerbated by the acts and inactions of the Whig administration led by Lord John Russell, Prime Minister of Great Britain, between 1846 and 1852.

- More than a million people perished as a direct result of the famine, and at least twice as many were compelled to leave the country as a result.

- In the latter part of the 19th century, the famine and other social, political and economic concerns contributed to a surge in Irish nationalist sentiment.

Independence Movement

Home Rule Movement

- The revival of Gaelic culture in Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries gave rise to a newfound sense of national pride and identity among the Irish people. All of these factors, especially the spread of democratic ideas and the rising demand for land reform, contributed to a renewed zeal for the fight for Irish independence.

- During this time, there was also a movement led by the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) that sought to constitutionally and peacefully bring about devolution for Ireland.

- The Home Rule movement was the leading political campaign of Irish nationalism, advocating for Ireland's autonomy within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Members of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) had been lobbying the British government for Home Rule since the 1870s. Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin (Irish Republican political party) was one such fringe group that advocated for Irish independence, although they were in the minority.

- The policy of Home Rule, which had previously failed in the legislature in 1886 and 1893, was on the verge of triumph in 1912 and was almost passed into law in 1914. Yet it still met with great opposition in Ulster, where the Protestant majority was unwilling to be placed under Catholic control.

Paramilitaries

- The Ulster Unionist Council led by Edward Carson and James Craig formally established the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). The UVF was a paramilitary organisation that pledged to use force to stop Irish Home Rule. However, nationalists responded by forming their own paramilitary group, the Irish Volunteers Force.

- All of these organisations aimed to smuggle weapons into Ireland and acquire proficiency in their usage.

- This escalation in military activity was a dangerous step towards all-out war, and it only served to heighten existing political tensions.

- On 18 September 1914, British parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914 (also known as the Home Rule Act) with an amending bill for the partition of Ireland introduced by Ulster Unionist MPs, but its implementation was immediately postponed by the Suspensory Act 1914 due to the outbreak of World War One.

- To assure the start of Home Rule after the war, most nationalists heeded their IPP leaders' and John Redmond's appeal to serve Britain and the Allied war effort in Irish battalions of the New British Army.

- Not all Irish Volunteers supported Ireland's participation in the war. Redmond led the faction of the volunteer movement, called the National Volunteers. Eoin MacNeill, who was in charge of the remaining Irish Volunteers, were hostile to the war and insisted that they would keep operating until Home Rule was officially approved.

- Within this volunteer organisation, a section led by the separatist

Irish Republican Brotherhood began to plan a rebellion against

British control in Ireland.

Easter Rising

- In 1916, the IRB led an armed uprising against the Crown known as the Easter Rising. On the basis of their inherent right to be a sovereign state, the IRB, led by Patrick Pearse, wanted to declare Irish independence from the United Kingdom and the creation of an Irish Republic. In Dublin, Pearse and his colleagues made public vows of independence before seizing public buildings.

- A week later, and with roughly 500 casualties, the revolt was put down, but the British reaction – executing the leaders and detaining 3,000 nationalist activists – enraged Irish public opinion.

Declaration of Independence

1918 General Election

- In April 1918, during WWI, the British government drafted a law (The Military Service no. 2 Act) that would enforce conscription in Ireland. This further alienated Irish nationalists and led to widespread protests during the 1918 Conscription Crisis.

- Irish people demonstrated their dissatisfaction at British policies in the 1918 general election by electing republican Sinn Féin to 70% (73 seats out of 105) of Irish seats. Sinn Féin committed not to sit in Westminster's British Parliament, but rather to establish an Irish Parliament.

- Following their overwhelming victory in the 1918 general election, 26 elected republican Sinn Féin members of parliament convened at the Dublin Mansion House to organise the formation of a revolutionary parliament named Dáil Éireann, Ireland's first self-governing assembly.

- The Conscription Crisis of 1918 was sparked by an effort by the British government to enforce conscription (military drafting) in Ireland during the First World War in April 1918.

- A conscription statute was approved, but it was never implemented; no Irishmen were conscripted into the British Army. Both the idea and the subsequent response galvanised support for political groups that promoted Irish secession and shaped events leading up to the Irish War of Independence.

- Arthur Griffith started Sinn Féin in 1905. Griffith favoured a peaceful settlement based on 'dual monarchy' with the United Kingdom, that is, two independent kingdoms with a single head of state and a restricted central government to regulate only areas of common interest.

- In 1918, however, under its new leader, Éamon de Valera, Sinn Féin came to favour gaining independence from Britain by an armed revolt and the foundation of an independent republic.

Declaration of Irish Republic

- George Gavan Duffy, Sean T O' Kelly and Piaras Beslai were among the committee members tasked with drafting a temporary constitution for the Dáil and preparing for its public inauguration.

- The First Dáil Éireann convened in the Mansion House on 21 January 1919. Thousands of people gathered outside, some of whom climbed lampposts to get a closer look. The Round Room and its gallery were packed with visitors, clergy and members of the press.

Members of the First Dáil - The Dáil's provisional constitution was read and overwhelmingly approved, after which the Irish Declaration of Independence was read in Irish and English, ratifying an Irish republic and rejecting British control. The assembly urged the 'Free Nations of the World' to accept their new government, and approved a provisional constitution.

Outbreak of the War

- The Dáil's stance was certain to draw a harsh reaction from Britain, but there was disagreement inside the body as to whether or not violence was the appropriate means to attain their aim. Nonetheless, at this time the IRB (Irish Republican Brotherhood) and the Irish Volunteers had already started pushing the country into war.

- Two men of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were ambushed and killed at Soloheadbeg, County Tipperary, on the day the Dáil met. This action heralded the beginning of the War of Independence.

- Seán Treacy, Seán Hogan, Séumas Robinson and Dan Breen took the initiative to plan and execute the Soloheadbeg Ambush.

- The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), Ireland's national police force, was a frequent target of political campaigns and physical assaults throughout the Irish War of Independence.

Irish Action

- Soon after Irish independence was declared, Sinn Féin urged the people of Ireland to shun the RIC as agents of the British government. Many police personnel were socially isolated as a result of the campaign.

- The Irish Republican Army's (IRA) campaign against the police was in full swing at the beginning of 1919. This resulted in a rise in Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) resignations and an inadequate police force in broad portions of southern Ireland.

- In the first phases of their movement, the IRA's primary challenge was a shortage of firearms. There were never quite enough weapons to match the number of eager soldiers. Therefore, prior to contemplating military action, each unit was entrusted with equipping itself.

- In order to get firearms like shotguns and revolvers, the IRA routinely attacked Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks and major landowners' homes.

- In addition, an IRA-controlled covert weapons factory was established in Dublin.

- Attacks on British government property, raids on guns and finances, and the assassination of key British officials were all initiated by volunteers. In Westport, County Mayo, Volunteers shot and killed Resident Magistrate John C Milling after he had remanded them to jail for illegal assembly and drilling. They adopted the uniformless, quick and aggressive tactics that the Boers had found to be so effective.

- Although certain republican leaders, like Éamon de Valera, favoured traditional conventional warfare to legitimise the new republic in the eyes of the world, Michael Collins and the larger IRA leadership rejected these methods since they had resulted in the military defeat of 1916. Others, such as Arthur Griffith, favoured a campaign of civil disobedience over violent conflict.

British Action

- The Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve, often known as Black and Tans, was created as a response to the falling number of police officers. The primary objective of the Black and Tans was to bolster police positions and aid the RIC in its fight against the IRA.

- In response to increasing levels of violence in the summer of 1920, the British government created the Auxiliary Division. The Auxiliaries were a RIC paramilitary squad tasked with conducting counterinsurgency operations against the republican troops. Because of their abundance of fully motorised and armoured vehicles, the Auxiliaries were considered a highly mobile and elite army.

- Like the Black and Tans, the Auxiliaries were notorious for their methods of intimidation, raids on private property, and violent attacks against citizens and towns, such as the burning of Cork.

- Midway through the year 1920, republicans took control of the majority of county councils, and British authority collapsed in the majority of the south and west, compelling the British government to implement emergency powers.

- The British Intelligence personnel were targeted by IRA units in Dublin on 21 November 1920 in a large-scale assassination attempt that left 14 men dead, at least 8 of which intelligence officials.

- In retaliation, a group of RIC Black and Tans and Auxiliaries killed 15 civilians and wounded 65 on a Gaelic football pitch in Dublin's Croke Park. The day was remembered as Bloody Sunday.

- 1920 Bloody Sunday, also known as the First Bloody Sunday, was one of the major incidents of the Irish War of Independence, which followed the proclamation of the Irish Republic and the establishment of its parliament, Dáil Éireann. The actions of the morning of 21 November, led by Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, were an attempt by the IRA in Dublin to destroy the British intelligence network in the city.

- A week later, the IRA murdered 17 Auxiliaries in County Cork at the Kilmichael Ambush.

- The conflict significantly escalated as a result of these tactics. On 10 December 1920, martial law was declared in the Munster counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary.

- In January 1921, it was extended to the other Munster counties of Clare and Waterford, as well as the Leinster counties of Kilkenny and Wexford. British soldiers burned down the city centre of Cork in retaliation for an ambush.

- In the first six months of 1921, around one thousand people were killed during the war. Violence was most severe in Dublin city, south Munster, and Belfast, but there was guerrilla action in all regions. Approximately 6,000 republicans were also imprisoned.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

- On 11 July 1921, a truce was established between the British and Irish Republican troops so that negotiations for a political solution could begin.

While discussions were taking place inside Whitehall, a crowd gathered outside to pray - On 6 December 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed by an Irish delegation as a result of the post-ceasefire negotiations.

- The treaty is officially known as the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, which concluded the War of Independence.

- The agreement was signed in London, by officials of the British government conducted by Prime Minister David Lloyd George and leaders of the Irish Republic, notably Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith.

- The treaty led to:

- Ireland becoming a dominion under the rule of King George V, and the new Irish Free State joining the British Commonwealth.

- Consolidation of the Government of Ireland Act, which reaffirmed the division of Ireland, leaving six largely unionist northern counties outside the Free State.

- The Dáil wearing an Oath of Allegiance to the King and renouncing the Irish Republic fought for by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

- For strategic reasons, the Royal Navy maintaining presence at three ports in southern Ireland.

- Following the signing of the treaty, the cabinet convened and engaged in heated debates, with the most contentious subjects including the dissolution of the Irish Republic and the acknowledgment of the King as Head of State.

- Following discussions, the cabinet voted four to three in favour of the deal. In the end, the Dáil narrowly approved the treaty by a vote of 64 to 57.

- The treaty resulted in Eamon de Valera's resignation as President of the Dáil.

- A civil war broke out in Ireland that lasted until 24 May 1923 and resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 people, including Michael Collins.

- In 1949, the Irish Free State attained complete independence and became the Republic of Ireland, having made significant progress towards independence during the subsequent decades.