Mao Tse-tung Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Mao Tse-tung to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese Communist Party

- Mao’s position in the People’s Republic of China

- Hundred Flowers Campaign

- The Great Leap Forward

- Great Chinese Famine

- Mao’s position in 1962

- Mao’s Personality Cult

- Cultural Revolution

- Conditions of China at Mao's death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Mao Tse-tung!

Mao Tse-tung was a Chinese Marxist theorist, statesman and revolutionary who became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party from 1949 until his death in 1976 and founder and chairman of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from 1949 to 1959. His philosophical ideas mainly centered on nationalism, feminism, traditional Chinese philosophy and Marxism, which would later on be collectively termed as Maoism and seen in the programmes of the CCP.

Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese Communist Party

- After the May Fourth Movement in 1919, anarchist and Marxist ideas started to spread widely in China, resulting in the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or CPC) in 1921. Since the establishment of the Republic of China, the party has been in sole control of the Chinese government.

- At the time of the founding of the CCP, China was still a divided and backward country ruled by power-greedy warlords. Because of constant wars with other factions, each warlord tried to receive foreign help, which resulted in foreign powers territorially and economically within China. The intellectuals who founded the CCP believed that Marxism would unite, strengthen and modernise China.

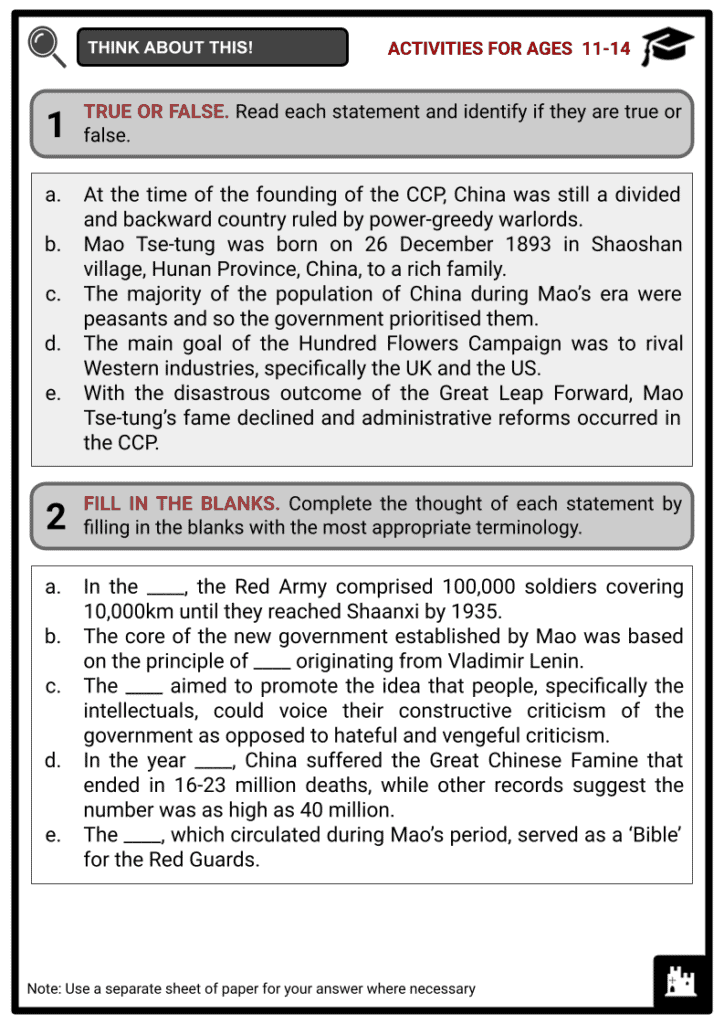

- In 1934, Chiang Kai-shek led a massive campaign against the CCP which forced the latter to escape towards the north. This event was eventually known as the Long March. In the Long March, the Red Army comprised 100,000 soldiers covering 10,000km until they reached Shaanxi by 1935. It is said that 95,000 soldiers died and this is the period where Mao Tse-tung gained leadership of the Red Army.

- Mao Tse-tung was born on 26 December 1893 in Shaoshan village, Hunan Province, China, to a poor peasant family. He was a staunch supporter of anti-imperialism in China. While working at Peking University, he adopted Marxism-Leninism and became a founding member of the CCP in 1911.

- Mao’s ideas mainly centered on:

- Nationalism

- Feminism

- Traditional Chinese Philosophy

- Marxism

- Mao believed that communism would be a tool for unifying China. He targeted poor peasants, as he believed that they were a clean slate and could be educated thoroughly. In unifying China, he was convinced that his people had all of the skills and expertise needed to mould their own destiny. In order to unify his country, a strong government under a communist party was needed to defend themselves against foreign control, mainly imperialism.

Overview map of the route of the Long March - Later on, Mao’s ideas would collectively be termed Maoism and be seen in the programmes of the CCP such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

- Mao believed that part of the unification of his country was to maximise the agricultural resources of China. Many were sceptical that communism/Marxism could only work in an industrialised society due to the prevalence of capitalism. Hence, in the CCP’s Great Leap Forward, the agricultural revolution was an important component resulting in a different view of communism.

- During the Chinese Civil War, Mao helped in the establishment of the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army. He became the leader of the CCP during the Long March. In the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Mao became the Chairman of the CCP from 1949 until his death in 1976.

Mao’s position in the People’s Republic of China

- Millions of peasants began to support Mao Tse-Tung’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which was initially the Red Army, as they were attracted by the promises of land. In the cities, middle-class families began to withdraw their support for Chiang Kai-shek due to worsening inflation and the Nationalists’ hostile attitude towards dissidents.

Mao Tse-tung - When the PRC was established in 1949, Mao believed that the new government was a ‘people’s democratic dictatorship’. The Chinese People’s Political Conference created a new constitution for China. It allowed for freedom of expression, freedom of religion, multi-party elections, and equal gender rights.

- The highest body of the new government was the National People’s Congress (Parliament). There was a State Council with Zhou Enlai as the appointed Premier. Mao became the first PRC President but he did not intend to act democratically. He gave himself all of the key roles – President, Chairman, Head of the PLA – for unlimited power.

- The core of the new government was based on the principle of democratic centralism. Originating from Vladimir Lenin, the principle entails that political decisions that result from voting are compulsory for all members of the party.

- As Mao needed to replace the Kuomintang officials, the party needed 2 million trained officials but there were only 720,000 trained CCP officials. Hence, he increased CCP membership to fill the positions, which resulted in mass party membership.

- By the end of 1952, the CCP was successfully running the military, education, police and trade unions through a Politburo.

- Mao used the PLA to maintain control in the country and had them hunt down 100,000 enemies of the state between 1950-1953. The PLA was also used to rebuild railways and roads. The peasants (proletariat) became the fundamental component of the new government in China.

- The majority of the population of China were peasants. Hence, the government prioritised them. They were needed for the new revolutionary army in which they would be trained in guerrilla tactics and would protect the CCP against capitalist attack.

- Part of the promotion of the ideals of the CCP was the enforcement of removing ownership of land from the wealthy landlords to the peasants. This was stipulated in the 1950 Agrarian Reform Law. Its main objective was equitable redistribution of land to landless peasants by seizing it from wealthy landlords. By 1953, the CCP had 6.5 million members.

- Being an agricultural country, Mao and his government decided that economic reforms should focus on this area. Hence, several policies were about the removal of land from landlords and its redistribution.

- Peasants were rewarded by the government and by 1952, 40% of land in China had been redistributed and 60% of peasants had benefited from the CCP’s redistribution of land. The government saw this as an opportunity to spread the message of classlessness in society. The main objective of Mao’s government was to increase the supply of food. Hence, through the redistribution of land, they came up with the concept of Four Freedoms.

- Four Freedoms

- Buy, sell and rent land

- Lend money to peasant farmers

- Hire labour needed for food production

- Trade

- It resulted in a 15% increase in food production by 1952 as the peasants were motivated to work for a profit. However, the government encountered problems. Bigger farms were needed to further increase food supply and the redistribution of land led to small-scale farming. Furthermore, more peasants were moving to urban areas as industrialisation was also taking place. Thus, Mao shifted his focus to cooperatives.

Hundred Flowers Campaign

- In 1956, Mao Tse-tung promoted the Hundred Flowers Campaign. It originated from the poem ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend’.

- The campaign aimed to promote the idea that people, specifically the intellectuals, could voice their constructive criticism of the government as opposed to hateful and vengeful criticism. Implicitly, he wanted to prove that the Chinese people were happier with the PRC and socialism compared to the Warring States.

- The country’s premier, Zhou Enlai, oversaw the campaign. Noticeably, the people did not heed the campaign for fear that they might be incriminated. At the beginning of the campaign, the government received a small amount of criticism, much of it conservative advice.

Hundred Flowers Campaign - As the government’s tone of request for criticism became more demanding, people began to feel secure and, by the spring of 1957, intellectuals began to send assertive suggestions and criticisms. Furthermore, university students and other Chinese citizens even organised meetings and rallies and produced posters and published articles calling for government reform.

- From 1 May until 7 June 1957, the premier’s office received millions of letters. One example was the students of Peking University, who created a ‘Democratic Wall’ on which they put posters criticising the government.

- On 8 June 1957, Mao Tse-tung stopped the campaign. Both he and Zhou Enlai did not expect the amount of criticism pouring out against the government. Their expectation was that the people were happier with the establishment of the PRC under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Thus, Mao did not see the letters as constructive criticism, rather as a direct threat to the government.

- As Mao stated, ‘poisonous weeds’ should be plucked out from the bed of flowers. They called for the round-up of intellectuals, students and other citizens who criticised the government and forced them to confess that they were part of a conspiracy to overthrow the regime. Many of them were sent to labour camps for ‘re-education’.

- After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev heavily criticised the old communism exemplified in the Hungarian Uprising. Thus, Mao believed that freedom of speech would be beneficial for the PRC, resulting in the launch of the Hundred Flowers Campaign. Many people were assured that voicing their criticism would not put them in danger. However, the opposite happened.

The Great Leap Forward

- In 1958, Mao Tse-tung called for the Great Leap Forward. The main goal of the programme was to rival Western industries, specifically the UK and the US. Being an agricultural country, Mao wanted China to become a modernised nation within five years by focusing on heavy industries and usage of modern agricultural techniques.

- With the success of agricultural cooperation and collectivisation, the population in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) grew rapidly by 1958. Hence, Mao Tse-tung’s administration saw radicalisation of agriculture as essential. In order to achieve this, the development of farm irrigation was needed and for its intensive success, communes were established.

- Mao Tse-tung wanted to surpass the US and the UK in terms of economic growth. However, he saw that the momentum of communism and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had declined. Mao therefore argued that the CCP needed to follow the political will of the people and established the Great Leap Forward.

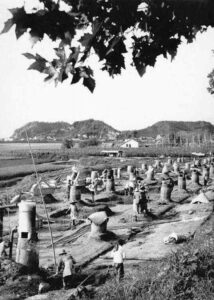

The Great Leap Forward: Communal Living

- Mao also mobilised the peasants in the communes to work and invest in steel manufacturing through backyard steel furnaces. This was part of Mao’s plan to make Chinese steel independent.

Communal Living - Though 90% of the peasants were able to produce steel, families were forced to meet quotas for production. Thus, some people melted their farm equipment, pans, pots and other cooking materials to produce steel. With no proper training, low-quality steel was produced.

The Great Leap Forward: Lysenkoism

- Also part of the Great Leap Forward was the adoption of Lysenkoism, a movement developed by Trofim Lysenko, the director of the Soviet Union’s Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences. It brought catastrophic results.

- Lysenkoism was a pseudo-scientific movement in which it was believed that farmers could cultivate ‘super crops’ 16x more productive than normal ones by exposing seeds to damp and then planting them deep underground and close together. The results in China were disastrous. Farmers in communes planted 15 million seeds an acre rather than 1.5 million, which created seed wastage upwards of 90%.

The Great Leap Forward: Four Pests Campaign

- The Four Pests Campaign was another action taken during the Great Leap Forward that was initiated by Mao towards the improvement of public hygiene.

- The Four Pests Campaign considered four pests, namely rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows, that were to be exterminated for spreading diseases such as malaria, plague and typhoid. The sparrow was on the list for consuming rice and seeds from fields.

Great Chinese Famine

- In 1959, China suffered the Great Chinese Famine that ended in 16-23 million deaths, while other records suggest the number was as high as 40 million.

Communal living - Furthermore, from 1959 until 1962, heavy industrial output dropped by 55% while light industrial output dropped by 30%. 25,000 state enterprises had to be shut down and new construction projects were cancelled. Around 8.5 million urban workers lost their jobs. The period from 1958 until 1960 is known as the ‘Three Bitter Years’ in China.

- Factors that led to the famine:

- Droughts, which persisted from 1959 until 1960.

- Failure of the Four Pests campaign and Lysenkoism.

- Poor planning in communes and of central government officials who were terrified of Mao Tse-tung.

- The Great Famine was not admitted until 1980. China continuously exported rice, hence, falling production was not noticed abroad. Seven million tons of grain were exported to finance industrial development in China. Furthermore, Mao Tse-tung did not ask for international aid.

- Stealing and robbery were rampant, prostitution grew, and starving families ate rats, worms, tree bark, leaves and even turned to cannibalism. Chinese officials only relied on the fertility rate for data, which dropped, and the mortality rate increased during this period.

Backyard furnaces for producing steel

Mao’s position in 1962

- With the disastrous outcome of the Great Leap Forward, Mao Tse-tung’s fame declined and administrative reforms occurred in the CCP. In 1959, Liu Shaoqi became the chairman of the PRC, replacing Mao who retained his position as the party chairman. Together with Deng Xiaoping, the general secretary of the CCP, they reformed the country’s economic policies to save face for Mao and the CCP.

- As a staunch communist, Mao wanted the people, specifically the peasants, to support a mass revolution and challenge CCP authority. Moreover, he wanted to establish a Cultural Revolution and to revise the curriculum at universities and colleges.

- Liu and Deng were condemned by Mao and other rightists as they were seen as ‘capitalist roaders’. The policies they implemented also included the political rehabilitation of some of the people imprisoned during the Hundred Flowers Campaign and Mao saw these changes as desertion from his political aims.

Mao’s Personality Cult

- Propaganda techniques were used by Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to ensure that communist policies would be propagated in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

- The Ministry of Culture ensured that anti-communist material was censored by controlling literature, movies, music and art. This was greatly felt during the Cultural Revolution.

- Propaganda posters played a vital role in delivering Mao’s communist ideals. The messages ensured that people were filled with the revolutionary spirit and that all people understood their roles and responsibilities in the PRC. Thought control was used to encourage people to embrace communist ideology.

- The fanaticism towards Mao Tse-tung fuelled the Cult of Mao, which made the CCP’s objectives successful. The cult intensified during the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s achievements were glorified while his shortcomings were concealed. Even when his policies failed, he was still revered by the people due to the cult developed by his propaganda ministry.

- Every medium possible was used to demonstrate to the people how amazing Mao was: posters, statues, books, speeches and art. One of the books circulated during this period was the Little Red Book, which served as a ‘Bible’ for the Red Guards. Through these forms, Mao was seen as the father of the nation and as a hero.

Cultural Revolution

- Mao encouraged his loyal supporters to denounce bourgeois ideas embedded in academic writing. He encouraged the students from universities and colleges to rebel against their teachers who were anti-revolutionaries. As the students responded enthusiastically to Mao’s heeds, he called them the Red Guards.

- Mao summoned the Red Guards for a mass rally in Tiananmen Square on 18 August 1966. For six hours, the people listened to speeches by Mao loyalists. Mao gave free rein to these people in attacking those who were against Mao’s socialism. When the group grew by one million members in Beijing, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution began.

Cultural Revolution propaganda poster - Mao further encouraged the Red Guards to attack the Four Olds. Since Mao’s order to condemn bourgeois ideas and destroy the Four Olds was not given with specific directives, the Red Guards followed it zealously. They distributed pamphlets, plastered cities with dazibao (big character posters), organised rallies, and delivered speeches.

- Four Olds:

- Old Culture

- Old Customs

- Old Habits

- Old Ideas

- China’s old culture was destroyed, specifically elements linked to its imperial history. Literary works were destroyed and burned. Authors and owners were harshly punished. Intellectuals, capitalists, Chinese wearing foreign outfits, and Catholic nuns were targeted as they were cowed and physically attacked.

- Upon the establishment of the Red Guards in 1966, its members swore to protect Mao Tse-tung’s socialist ideals and strictly followed Chairman Mao’s statement to rebel against the system and to destroy the Four Olds.

- In February 1967, after serving their purpose, Mao tried to shut down the movement primarily led by students in order to stabilise the government. The argument was based on the notion that these young students were too radical and violent and could cause an uncontrollable upheaval.

- Through the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the Red Guards, were suppressed in rural areas such as Anhui, Fujian, Hubei, Hunan and Sichuan, they were strictly ordered to continue their education and radical movements were deemed ‘counter-revolutionary’.

- The Red Guards reacted aggressively against the turn of events, resulting in conflict with the PLA. Through Mao’s orders, the PLA was instructed to restore order in the country on 5 September 1967.

- Violence occurred towards the movement, even resulting in a mass execution of Red Guards in Guangxi province. By 1968, the movement ended with Mao’s remorseful order of shutting it down.

- The Cultural Revolution was a double-edged sword on the part of the government. As they wanted to tighten its control in China by spreading Mao Tse-Tung’s socialist ideals, it brought misery to millions of people. According to the official statistics, around 36,000 people died during the revolution.

- In 1966, several universities were shut down as the students joined the Red Guards. Moreover, educators were a prime target for attack and, as a result, all schools, colleges and universities were closed for two years. Several intellectuals, including professors and academics, were arrested, tortured and killed. Those who weren’t killed were sent to re-education camps.

- The funding for private education of children of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials was cut off and diverted to rural-based students to encourage equality. Furthermore, with the establishment of the Down to the Countryside Movement in 1968, educated youths known as zhishi qingnian were sent to rural areas to do agrarian chores as part of re-education. Hence, depriving the zhishi qingnian or rusticated educated youths the opportunity for higher education.

Conditions of China at Mao’s death

- Mao’s health declined in his last years. In March and July of 1976, he suffered two major heart attacks and then a third one on 5 September, which rendered him invalid. He died on 9 September 1976 at the age of 82.

- At the time of his death, China was in a state of political and economic dilemma. The Cultural Revolution, added to conflicts among different factions, had left the country poorer than it had been in 1965. Many schools had been closed and an entire generation of youngsters were unable to obtain an education.

- After Mao’s death, the Gang of Four were expected to take complete power of the government. However, they were eventually outmanoeuvred by the Politburo.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Mao_Zedong_sitting.jpg/800px-Mao_Zedong_sitting.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Map_of_the_Long_March_1934-1935-en.svg/1024px-Map_of_the_Long_March_1934-1935-en.svg.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0a/Mao_Zedong_in_1959_%28cropped%29.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/46/Hundred_Flowers_Campaign.jpg?20130930141256

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a0/People%27s_commune_canteen2.jpg/296px-People%27s_commune_canteen2.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/29/People%27s_commune_canteen.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Backyard_furnace4.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/c/c6/Cultural_Revolution_poster.jpg