Marcus Garvey Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Marcus Garvey to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early Life

- Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA)

- Criminal Charges Against Garvey

- Later Years

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Marcus Garvey!

Marcus Garvey and his organisation, the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA), symbolise the history of the African-American large movement. Garvey and the UNIA had built 700 branches in 38 states by the early 1920s, proclaiming a Black nationalist ‘Back to Africa’ message. His ideals, as a Black nationalist and Pan-Africanist, were known as Garveyism. He was praised for instilling pride and self-worth in Africans and the African diaspora in the face of pervasive poverty, prejudice and colonialism. He is largely regarded as a national hero in Jamaica.

EARLY LIFE

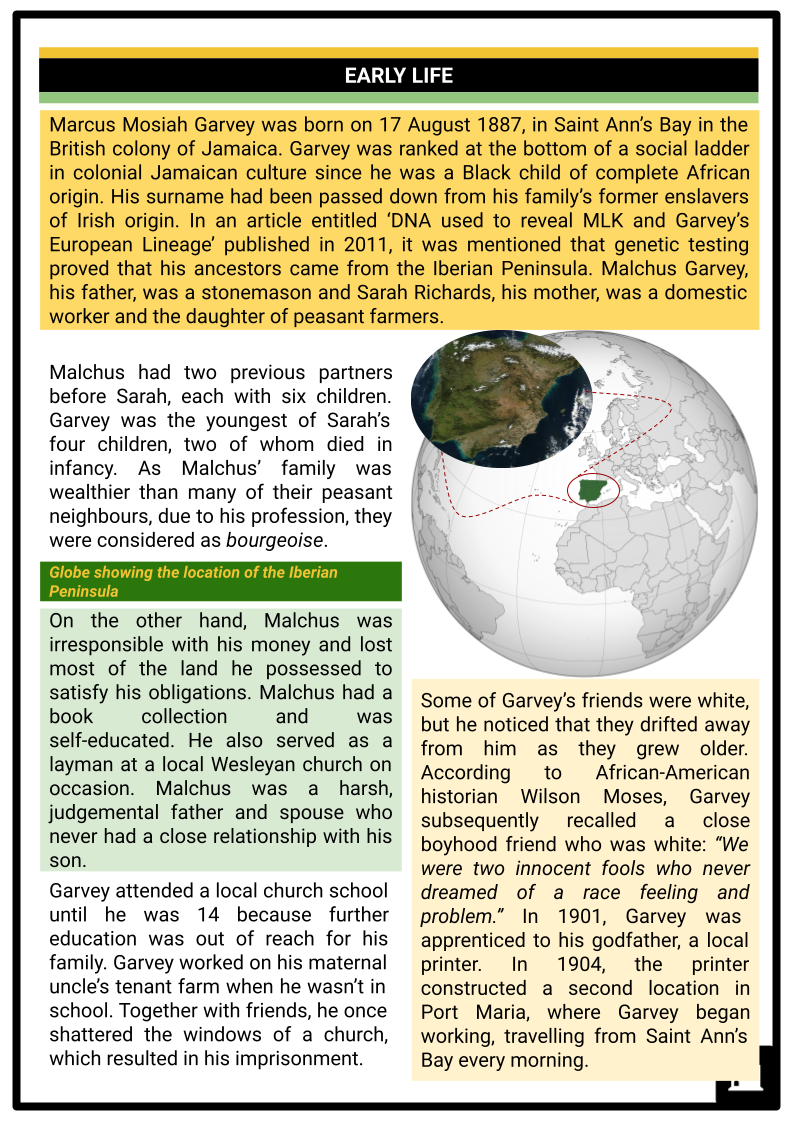

- Marcus Mosiah Garvey was born on 17 August 1887, in Saint Ann’s Bay in the British colony of Jamaica. Garvey was ranked at the bottom of a social ladder in colonial Jamaican culture since he was a Black child of complete African origin. His surname had been passed down from his family’s former enslavers of Irish origin. In an article entitled ‘DNA used to reveal MLK and Garvey’s European Lineage’ published in 2011, it was mentioned that genetic testing proved that his ancestors came from the Iberian Peninsula. Malchus Garvey, his father, was a stonemason and Sarah Richards, his mother, was a domestic worker and the daughter of peasant farmers.

- Malchus had two previous partners before Sarah, each with six children. Garvey was the youngest of Sarah’s four children, two of whom died in infancy. As Malchus’ family was wealthier than many of their peasant neighbours, due to his profession, they were considered as bourgeoise.

- On the other hand, Malchus was irresponsible with his money and lost most of the land he possessed to satisfy his obligations. Malchus had a book collection and was self-educated. He also served as a layman at a local Wesleyan church on occasion. Malchus was a harsh, judgemental father and spouse who never had a close relationship with his son.

- Garvey attended a local church school until he was 14 because further education was out of reach for his family. Garvey worked on his maternal uncle’s tenant farm when he wasn’t in school. Together with friends, he once shattered the windows of a church, which resulted in his imprisonment.

- Some of Garvey’s friends were white, but he noticed that they drifted away from him as they grew older. According to African-American historian Wilson Moses, Garvey subsequently recalled a close boyhood friend who was white: “We were two innocent fools who never dreamed of a race feeling and problem.” In 1901, Garvey was apprenticed to his godfather, a local printer. In 1904, the printer constructed a second location in Port Maria, where Garvey began working, travelling from Saint Ann’s Bay every morning.

- Garvey moved to Kingston in 1905 and boarded in Smith Village, a working-class community. He found work with the P.A. Benjamin Manufacturing Company, a printing branch in the city that manufactures products. He soon ascended through the corporation’s ranks, becoming its first Afro-Jamaican foreman.

- Garvey’s sister and mother had grown estranged from his father and relocated to join him in the city. An earthquake struck Kingston in January 1907, destroying much of the city. He, his mother and his sister were forced to sleep outside for several months. His mother died in March 1908.

- Garvey became a trade unionist vice president of the Printers’ Union’s compositors division and played a key role in the November 1908 print workers’ strike. The strike was called off several weeks later, and Garvey was fired. Garvey became increasingly enraged by the disparities in Jamaican society due to these experiences.

- Garvey became the first assistant secretary of Jamaica’s first nationalist movement, the National Club, in April 1910. The group sought to depose Jamaica’s Governor, Sydney Olivier, and to stop the influx of Indian coolies, or unskilled/indentured workers, who were viewed as a source of economic competition by the established population.

- Garvey began publishing a magazine, Garvey’s Watchman (named after George William Gordon’s The Watchman), in early 1910, but it only lasted three issues. He said it had a circulation of 3,000, which was probably an exaggeration. Garvey also took elocution classes from radical journalists.

- Garvey regarded pan-Africanist Joseph Robert Love as his mentor. Garvey joined several public speaking competitions because of his improved ability to talk in Standard English.

UNIVERSAL NEGRO IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION AND AFRICAN COMMUNITIES LEAGUE (UNIA)

- Garvey left Jamaica at age 23 and travelled around Central America before settling in England for a while. During his travels, he grew convinced that the only way to better the plight of Black people was to unite them. To that aim, he left England aboard the SS Trent on 14 June 1914 and returned to Jamaica on 15 July 1914. Later the same month, in Kingston, he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, abbreviated as UNIA, to unite all of Africa and its diaspora.

- It began with simply a few members. Many Jamaicans were suspicious of the group’s prominent usage of the name Negro, which was frequently used as an insult at the time. Garvey, on the other hand, embraced the term about people of African origin.

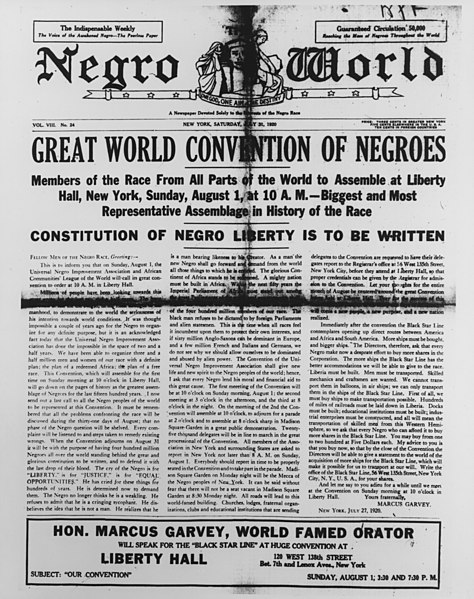

- On 17 August 1918, the Negro World was established as a weekly journal to express the organisation’s beliefs. Garvey submitted a front-page editorial each week in which he articulated the organisation’s viewpoint on many issues concerning people of African descent worldwide in general and the UNIA in particular.

- The publication eventually claimed a circulation of 500,000 and was printed in various languages. It had a page just for female readers, covered international events involving individuals of African heritage, and was disseminated throughout the African diaspora until it was discontinued in 1933.

- The Negro World was financially supported by philanthropists such as Madam CJ Walker, but six months after its establishment, it made a special plea for funds to stay afloat. Several journalists sued Garvey for neglecting to pay them for their contributions, which was widely advertised by competitor media. At the time, there were over 400 Black-run newspapers and periodicals in the United States (US).

- By the conclusion of its first year, the circulation of Negro World had surpassed 10,000 copies, which were distributed not only in the US but also in the Caribbean, Central and South America. The publishing was prohibited on some British West Indian islands.

- Following the conclusion of the First World War, US President Woodrow Wilson stated his desire to make a 14-point proposal for world peace at the upcoming Paris Peace Conference. Garvey and other African-American leaders formed the International League for Darker People to persuade Wilson and the conference to pay greater consideration to the demands of people of colour. However, their delegates needed travel documentation.

- The UNIA dispatched a young Haitian, Eliezer Cadet, to the conference at Garvey’s request. Despite these efforts, the political leaders that assembled in Paris mostly ignored non-European people’s viewpoints, instead expressing their support for sustained European colonial control.

- The US government believed that the October Revolution in Russia would incite African-Americans to engage in revolutionary conduct. Therefore, military intelligence directed Major Walter Loving to investigate Garvey. The October Revolution was the second and final significant phase of the 1917 Russian Revolution, in which the Bolshevik Party won power in Russia, establishing the Soviet state.

- John Edgar Hoover of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), now Federal Bureau of Investigation, determined that Garvey was politically subversive and should be deported from the US, adding his name to the list of persons who would be targeted in the upcoming Palmer Raids. The BOI brought Garvey’s name to the Labour Department under Louis F Post to certify the deportation. However, Post’s department declined, claiming that the case against Garvey was not substantiated.

STRUGGLES OF THE UNIA

- The UNIA expanded quickly, and in less than 18 months, it had branches in 25 states and divisions in the West Indies, Central America and West Africa. The precise membership is still being determined. However, Garvey, infamous for exaggerating numbers, claimed it had two million members by June 1919.

- Although there was considerable crossover in membership between the two groups, it remained smaller than the more established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a civil rights organisation in the United States. The NAACP and UNIA took different approaches: the NAACP was a multi-racial organisation that supported racial integration, whereas the UNIA was a Black-only organisation.

- There were disagreements between the UNIA and the NAACP, and the latter’s supporters accused Garvey of impeding their efforts to achieve racial unification in the US. Garvey was critical of NAACP head William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. Du Bois sought to disregard Garvey as a demagogue but also wanted to understand everything he could about Garvey’s movement.

- Garvey also established the African Legion, a group of uniformed men who participated in UNIA parades. Legion members formed a secret service, which provided Garvey with intelligence about group members. The Legion’s establishment alarmed the BOI, which dispatched its first full-time Black agent, James Wormley Jones, to infiltrate the UNIA.

- Garvey formed the Negro Factories League in January 1920, through which he constructed a chain of grocery stores, a restaurant, steam wash and publishing business. The UNIA hosted the First International Conference of the Negro Peoples in Harlem in August 1920. Gabriel Johnson, the Mayor of Monrovia, Liberia, attended this march.

- At the meeting, UNIA delegates elected Garvey as the Provisional President of Africa, tasked with establishing a government-in-exile capable of assuming control of the continent after European colonial rule ended through decolonisation.

BLACK STAR LINE

- Garvey and the other UNIA members founded a shipping company known as the Black Star Line. The shipping line was established to allow the transit of goods and, later, African-Americans throughout the African global economy.

- The Black Star Line became an important component of Garvey’s contribution to the Back-to-Africa campaign, but it was generally unsuccessful due in part to federal agent infiltration. It was one of many enterprises founded by the UNIA, including the Universal Printing House, the Negro Factories Corporation, and the widely circulated and extremely profitable Negro World weekly newspaper.

- The Black Star Line and its successor, the Black Cross Navigation and Trading Company, operated between 1919 and 1922. It is still a significant emblem for Garvey supporters and Pan-Africanists today.

CRIMINAL CHARGES AGAINST GARVEY

- Garvey was arrested and charged with mail fraud in January 1922 for advertising the sale of stocks in a ship, the Orion, that the Black Star Line did not yet own. He was released on $2,500 bail. Hoover and the BOI were determined to get a conviction as they had also received complaints from several Black Star Line stockholders, who urged them to investigate the situation further.

- Garvey spoke out against the allegations, but he blamed them on competing African-American groups rather than the state. In addition to alleging angry former UNIA members, he claimed in a Liberty Hall speech that the NAACP was behind the conspiracy to imprison him. The mainstream press picked up on the claim, portraying Garvey as a scam artist who had duped African-Americans.

- Garvey said the Black Star Line’s operations would be halted following his arrest. Garvey met with Edward Young Clarke, the Imperial Wizard pro tempore of the Ku Klux Klan, at the Klan’s offices in Atlanta in June 1922. The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is the name of several historical and current American white supremacists, far-right terrorist organisations and hate groups.

- The meeting between Garvey and the KKK quickly became public, and it was featured on the front pages of numerous African-American newspapers, provoking great outrage. Following the disclosure, several notable African-Americans started the Garvey Must Go campaign, including Chandler Owen, Asa Philip Randolph, William Pickens and Robert Bagnall.

- Garvey had some success in 1922 as well. Hubert Fauntleroy Julian, the country’s first Black pilot, joined the UNIA and performed aerial feats to increase the organisation’s visibility. He also succeeded in gaining a UNIA mission to the League of Nations, sending five members to Geneva to represent the organisation.

- Garvey urged for the impeachment of several top UNIA officials at the August 1922 conference, including Adrian Johnson and JD Gibson, and claimed that the UNIA cabinet should be appointed directly by him rather than elected by the organisation’s members. When they refused to quit, he resigned as leader of the UNIA and Provisional President of Africa, most likely to force their resignations.

- He then publicly criticised another senior member, Reverend James Eason, and successfully rejected him from the UNIA. With Eason gone, Garvey urged the remainder of the cabinet to resign, which they did, and he resumed his role as the organisation’s leader. In September, Eason founded the Universal Negro Alliance, a rival organisation to the UNIA. Garveyites slew Eason in New Orleans in January 1923. Hoover felt that senior UNIA members had ordered the killing despite Garvey’s public denial. Following the murder, eight prominent African-Americans publicly accused Garvey of killing Eason.

- They encouraged the Attorney-General to file criminal charges against Garvey and dissolve the UNIA. After being postponed at least three times, the trial on the mail fraud charges of Garvey and other defendants began in May 1923. Garvey’s attorney, Cornelius McDougald, persuaded him to plead guilty to secure a low sentence before the trial started. Still, Garvey refused, dismissing McDougald and deciding to represent himself in court. The jurors adjourned for ten hours on 18 June to deliberate on the verdict. Garvey was found guilty, but his three co-defendants were not.

- In September, Judge Martin Manton granted Garvey bail for $15,000, which the UNIA later increased, while he challenged his conviction. He toured the US as a free man, giving a speech at the Tuskegee Institute. Early in 1925, the Court of Appeal upheld the initial court verdict. Garvey was in Detroit at the time and was arrested on his way back to New York City on a train.

- Due to a signature campaign, Garvey was set free and returned to Jamaica in 1928. Supporters in Kingston hailed Garvey. UNIA members raised $10,000 to assist him in settling in Jamaica, with which he purchased a spacious property in an affluent suburb dubbed Somali Court.

LATER YEARS

- When Garvey was freed from prison after serving three years of his term, he proceeded to Geneva, Switzerland, to speak before the League of Nations on race and the global abuse of people of colour. He returned to Jamaica a few months later and founded the People’s Political Party, the country’s first contemporary political organisation. Its agenda prioritised workers’ rights and the disadvantaged.

- Garvey moved to London in 1935, living and working until his death at 52. Marcus Garvey died on 10 June 1940 as a result of complications caused by two strokes. Due to the Second World War travel restrictions, he was initially buried in St Mary’s Roman Catholic cemetery in Kensal Green, London. However, on 13 November 1964, his remains were exhumed and interred beneath the Marcus Garvey Memorial in Kingston, Jamaica’s National Heroes Park.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who is Marcus Garvey?

Marcus Garvey was a Jamaican political leader, publisher, journalist, orator who became a prominent figure in the early 20th-century Pan-African movement.

- What is Marcus Garvey best known for?

Marcus Garvey is best known for his leadership in the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and his promotion of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism.

- What is the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)?

The UNIA was founded by Marcus Garvey in 1914. It aimed to unite people of African descent worldwide, promote economic self-sufficiency, and foster a sense of pride in African heritage.