Montagu Declaration Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Montagu Declaration to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background of the Montagu Declaration

- Reactions in India and Provisions of the India Act 1919

- Results of the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Montagu Declaration!

Between 1917 and 1922, Edwin Samuel Montagu was India’s Secretary of State. He delivered an important speech outlining the aim of British policies in India in the House of Commons on 20 August 1917. In a discussion in the British House of Commons the month before, he had launched a vicious attack on the entire system by which India was governed. The speech is often referred to as the August 1917 Declaration or the Montagu Declaration.

BACKGROUND OF THE MONTAGU DECLARATION

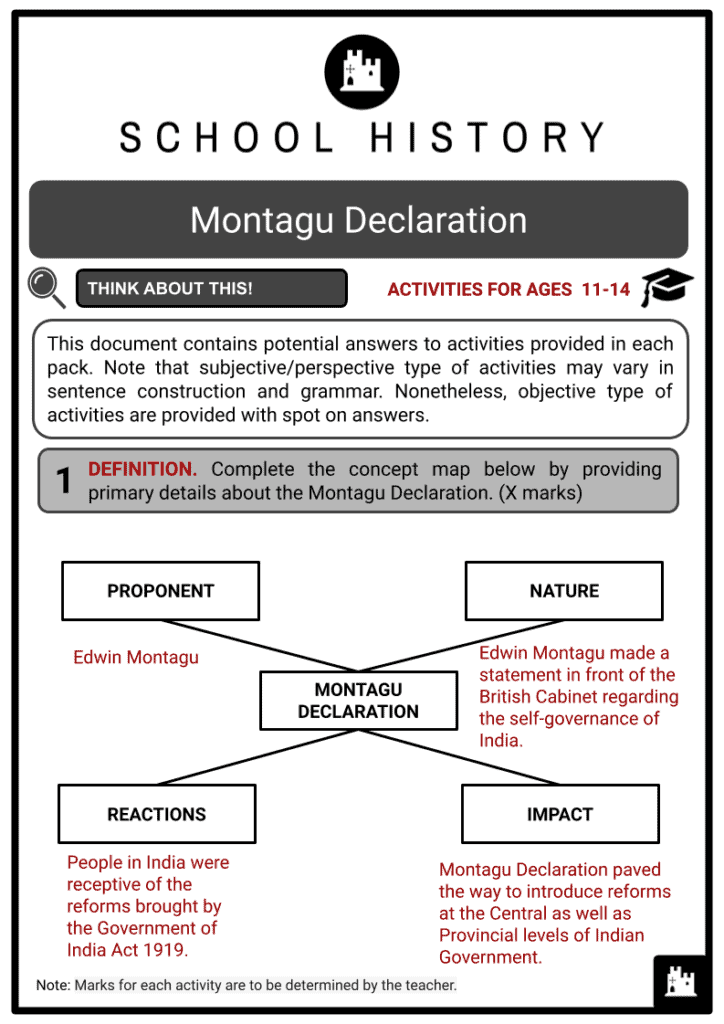

- After Austen Chamberlain resigned in June 1917 due to the Turkish conquest of Kut in 1916 and the subsequent surrender of an Indian army deployed there, Edwin Montagu was appointed Secretary of State for India. He presented a draft of a proposed statement to the British Cabinet outlining his commitment to work for the gradual emergence of free institutions in India with a view to eventual self-government.

- Based on the opinion of Lord Curzon, India’s former Viceroy, this placed too much emphasis on Montagu’s efforts to achieve self-government.

- As a result, Lord Curzon advised Montagu to focus on increasing Indian participation in all areas of government and developing self-governing institutions to gradually achieve responsible government in India as a part of the British Empire.

- In place of Montagu’s initial statement, the Cabinet adopted the statement with Curzon’s revision. The Montagu Declaration was titled: ‘Increasing association of Indians in every branch of administration, and the Gradual development of self-governing Institutions with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible governments in India as an integral part of the British Empire’. The phrase ‘responsible government’ emphasised the need for elected officials to be held accountable.

- To debate the introduction of limited self-government to India and the protection of minority communities’ rights, Montagu travelled to India in the latter part of 1917 to meet with Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy of India at that time, and leaders of the Indian community.

- Montagu drafted a report with Bhupendra Nath Bose (President of the Indian National Congress), Lord Donoughmore (British Conservative Party politician), William Duke (Scottish Civil Servant) and Charles Roberts (British Liberal Party politician).

- Montagu spoke with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Mahatma Gandhi, and other key figures in India. A thorough report on Indian Constitutional Reforms was written based on the meetings between Montagu, Chelmsford and Indian leaders. In July 1918, this report was made available.

- The 1919 Government of India Act was based on this report. The Montagu Declaration was referred to as the Magna Carta of India because it came about more than 15 years after Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858.

- Since a sizable majority of the members of the provincial legislative councils were elected, the changes at the local level were quite significant. The nation-building ministries of India’s government were put under ministers in a system known as diarchy, who were each personally accountable to the assembly. Executive councillors appointed by the Governor were in charge of maintaining the departments that made up the framework of British authority.

- The executive councillors were accountable to the Governor and sometimes to the British government. Diarchy was instituted in the provinces by the Act of 1919. As a result, there was a distinct division between the rights of the central and provincial governments.

- The rights over defence, foreign affairs, telegraphs, railways, postal services, foreign trade, etc., were all on the main list. The provincial list covered jail, police, justice, public work, sanitation, health and education.

- The centre was given control over the authorities not listed among the states. The Governor had the last say in any disputes involving the “reserved” and “unreserved” functions of the State (the former covered finance, police, revenue, publishing of books, etc., while the latter included health, sanitation, local-self government, etc.). The Diarchy was established in 1921 in Bengal, Madras, Bombay, the United Provinces, the Central Provinces, Punjab, Bihar and Orissa, and Assam; it was then expanded to include the North-West Frontier Province in 1932.

REACTIONS IN INDIA AND PROVISIONS OF THE INDIA ACT 1919

- Since many Indians had fought alongside the British in the First World War, they anticipated receiving far more lenient treatment. The Muslim League and the Indian National Congress joined forces to call for self-rule. The Government of India Act 1919 did not meet political aspirations. The Rowlatt Acts, which were first passed in 1919, restored limits on the press and freedom of movement after the British repressed resistance.

- Despite the unified opposition of the Indian council members, these policies were rushed through the legislative body. In protest, several council members, including Jinnah, quit.

Mahatma Gandhi - These actions were primarily viewed in India as betraying the populace’s ardent support for the British war effort.

- The Rowlatt Acts were the target of Gandhi’s first-ever statewide protest, which peaked in the Punjab. Amritsar’s predicament deteriorated in April 1919 when General Reginald Dyer, a British military officer, ordered his soldiers to fire on protesters crammed into a small plaza, killing at least 379 civilians.

- General Dyer was fired due to the Hunter Inquiry’s recommendation on his action. Many British residents backed Dyer because they believed the Hunter Inquiry had mistreated him. General Dyer received a £26,000 donation from the conservative Morning Post, and Montagu’s censure resolution was almost successful because of Sir Edward Carson, an Irish unionist politician.

- The first approach of reluctant cooperation ended after the Amritsar Massacre further fuelled Indian nationalist feelings.

- Many young Indians wanted quicker progress towards their country’s independence and were dissatisfied by the lack of promotion as British took over the administration’s old roles.

- Delegates to the Indian National Congress annual meeting in September 1920 agreed with Gandhi’s call for swaraj, or self-rule, either within the boundaries of the British Empire or outside of it if necessary.

- The swaraj called for a strategy of non-cooperation with British control. Hence Congress decided not to run any candidates in the 1921 elections convened due to the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms.

General Reginald Dyer

PROVISIONS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT 1919

- Diarchy was established in the shape of the Executive Councillors and Ministers, two classes of administrators.

- The Governor headed the executive branch of the province government.

- The subjects were divided into the reserved list and the transferred list.

- The Governor and councillors were in charge of the reserved list, and the ministries were in charge of the transferred list.

- The elected Legislative Council members made the nominations for the ministers. Unlike the councillors, they had to answer to the legislature.

- With almost 70% of the members being elected, the size of the legislative bodies increased. The act also included provisions for class and communal electorates. There were certain restrictions on women’s voting rights, nevertheless.

- The Governor had the power to veto decisions made by the council. The Governor-General served as the top executive officer at the federal level of government.

- The Legislative Assembly, the forerunner of the Lok Sabha, and the Council of State, the predecessor of the Rajya Sabha, were both introduced in this report as the two houses of the bicameral legislature.

- Three of the eight members of the Viceroy’s executive council had to be Indians.

- Elections were implemented, but the right to vote was only partially universal. Only a select group of people who were titled, wealthy or in positions of authority were eligible to vote.

- For the first time, the statute allowed for creating a public service commission.

- It also resulted in establishing an Indian High Commission in London.

RESULTS OF THE MONTAGU-CHELMSFORD REFORMS

- The Montagu-Chelmsford Report stipulated that a survey be conducted after ten years. Sir John Simon of the Simon Commission, a group of seven members of the British Parliament under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon, was in charge of the study that suggested additional adjustments in this regard. Three roundtable discussions occurred in London in 1930, 1931 and 1932. However, they did not make any progress.

- The main contention between the Indian National Congress and the British was the retention of separate electorates for each community, which the Congress opposed.

- The 1935 passage of the revised Government of India Act continued the self-government reforms initiated by the Montagu-Chelmsford Report.

- The report was significant because it marked the beginning of actual action to involve more Indians in running their nation. Elections were implemented, undoubtedly increasing political consciousness among Indians with at least some education.

- However, the improvements didn’t go far enough to ease Indian nationalists’ complaints and justifiable demands. The Viceroy still had a lot of power to make the legislature less effective. The franchise had a very restricted and limited scope.

Excerpt from the MONTAGU DECLARATION

Then we must not pass over lightly the problem of the villager. No system of representation will be satisfactory unless the agricultural population has, at any rate, some part and share in it. There are various ways in which it could be done, some of them indirect—local organisations of various kinds. I am perfectly certain that a Committee such as the right hon. Gentleman has been referring to to-day must face this village problem, and if it goes there and explores the possibilities of getting representative village opinion, it will discover several ways of carrying that instruction of ours into effect. Another class of the community which ought to be, and must be, represented is that of the workmen. Anyone who goes to Bombay and Calcutta and sees that extraordinary weltering mass of abandoned men living in insanitary filth, swarming upstairs and along corridors just like bees in a hive, must wonder how on earth they can live at all. No system of self-government can be satisfactory unless people in those conditions find somehow or other an access into the various governing assemblies and provincial and Imperial legislatures. I believe it is possible. I believe, for instance, that organisations like the Servants of India can make suggestions as to how that population is to be represented. In any event, hand them over to the lawyer, to the landowner, and to the big capitalists of Calcutta and Bombay and the condition of those people will be worsened rather than improved. We must, in weakening the sort of fatherly control that has been exercised up to now, put some weapons in the hands of the wage-earning masses of the industrial centres in India which will mean that they will be represented on the legislative councils, both local and Imperial.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What were the Montagu Declaration?

The Montagu Declaration was a speech delivered by Edwin Samuel Montagu, India’s Secretary of State to the House of Commons, which outlined his plans for increasing Indian participation in self-governance.

- What was the result of the Montagu Declaration?

The Montagu Declaration resulted in the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, also known as the Government of India Act 1919, which aimed to give Indians a more significant role in governance while maintaining British control.

- What was the reaction in India?

Nationalists criticised the declaration as they demanded self-government or home rule. Despite the aim of incorporating Indians into the government, Britain had no intentions of ceding powers.