Ostpolitik Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Ostpolitik to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Ideological Roots and Intentions

- Ostpolitik and Policy on Germany

- New Ostpolitik

- Second Phase of Ostpolitik

- Opposition in Eastern Europe

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Ostpolitik!

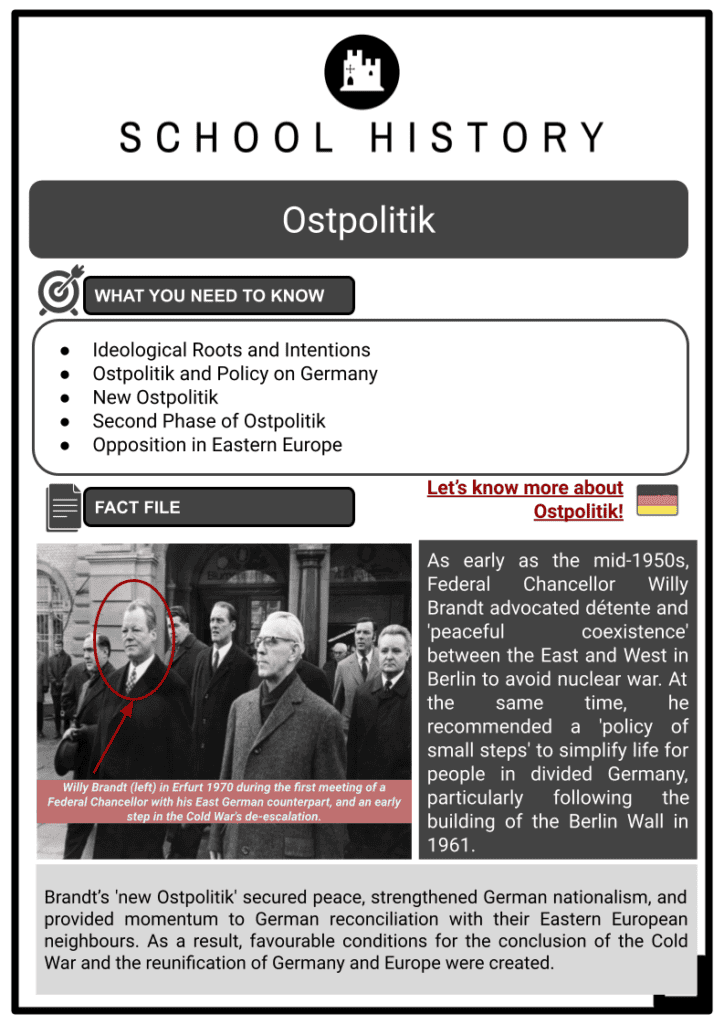

As early as the mid-1950s, Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt advocated détente and 'peaceful coexistence' between the East and West in Berlin to avoid nuclear war. At the same time, he recommended a 'policy of small steps' to simplify life for people in divided Germany, particularly following the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961.

Brandt’s 'new Ostpolitik' secured peace, strengthened German nationalism, and provided momentum to German reconciliation with their Eastern European neighbours. As a result, favourable conditions for the conclusion of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany and Europe were created.

IDEOLOGICAL ROOTS AND INTENTIONS

- Willy Brandt's perspective on Ostpolitik and German strategy dates back to the early years of the Cold War, which split Germany (East and West), Europe and the world in 1948. The failed public uprisings in East Germany in 1953 and Hungary in 1956 convinced Berlin's social democrats that communist authority could not be ended violently if a nuclear war was to be avoided.

- In his judgement, only a policy of détente, 'peaceful coexistence', and exchanges between the blocs would help the free, democratic West overcome the communist system in the East in the long run.

- As Governing Mayor of Berlin in 1958, Brandt called for the Federal Republic to execute 'Ostpolitik' in addition to integrating and closely cooperating with its Western partners.

- He intended improved connections with the Soviet Union and the revival of links with communist-ruled countries in Eastern Europe, most notably Poland.

- Even before he was elected Chancellor, he advocated for and promoted programmes to reduce tensions between the two German states, primarily in the interest of cross-border trade. His suggested new Ostpolitik argued that the Hallstein Doctrine did not destabilise the communist authority or even improve the situation of Germans in the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

- Brandt felt that working with the communists would promote meetings between East and West Germany. Nonetheless, he emphasised that his new Ostpolitik did not disregard the Federal Republic's close ties with Western Europe and the United States, nor its membership in NATO.

- According to German biographer Helga Haftendorn, several West European countries entered a more adventurous eastwards policy period. When Brandt became Chancellor in 1969, the same politicians feared a more independent German Ostpolitik, which they believed would become a new 'Rapallo'.

- France believed that after détente, West Germany would become more assertive: Brandt eventually resorted to blackmailing the French government into supporting his policies by withholding German financial contributions to the European Common Agricultural policies.

- RAPALLO was a treaty signed by the German Republic and Soviet Russia that renounced all territorial and financial claims against each other and established amicable diplomatic relations.

OSTPOLITIK AND POLICY ON GERMANY

- The 'policy of small steps' in Berlin foreshadowed a new attitude between West Germany and East Germany that gradually developed in the 1960s.

- Beginning in late 1966, the Grand Coalition in Bonn, led by Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger, instituted significant course corrections, to which the Foreign Minister at that time, Willy Brandt, and Egon Bahr (Chief of Planning) made substantial contributions.

- The CDU, CSU and SPD supported international détente and believed that resolving the problem between East and West Germany was only conceivable within a European peace treaty. Aside from that, the coalition partners were united in their efforts to reach non-aggression treaties and seek reconciliation with their Eastern European neighbours.

- GRAND COALITION is a term in German politics that refers to a governing coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD), which have historically been the major parties in most state and federal elections since 1949.

Map of Poland’s western border - However, diplomatic relations were established only with Romania in 1967. The remaining Eastern Bloc countries, under pressure from the Soviet Union, the GDR and Poland, opposed rapprochement with the Federal Republic.

- For the rapprochement policy to be implemented, Willy Brandt advocated for the first time in 1968 for Poland's western border to be recognised as the Oder-Neisse line.

- THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AND GERMANY’S POST-WAR TERRITORIAL LOSSES

- The border included the former Prussian areas of Posen and West Prussia that were not lost to Poland in 1918.

- Except for Saxony, all of the regions of Germany depicted on this map were part of the pre-war state of Prussia.

- Danzig was a League of Nations-managed free city.

- Despite being West of the Oder-Neisse line, Poland annexed Stettin and the surrounding area.

- Despite Brandt's advice, the CDU and CSU maintained that the GDR was not a state and that only the Federal Republic represented all Germans and all of Germany. Kiesinger and the Christian Democrats opposed Brandt's urgent recommendation to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

- NUCLEAR NON-PROLIFERATION TREATY is an international treaty whose purpose was to prevent the spread of atomic weapons and weapons technology, to foster cooperation in the peaceful uses of atomic energy, and to advance nuclear and general and complete disarmament.

NEW OSTPOLITIK

- Only the social-liberal government of Willy Brandt (SPD) and Walter Scheel (FDP) dared to break old taboos beginning in 1969. They no longer disputed the existence of a second German state, the GDR, ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and gave up the claim to represent all Germans.

- In 1970, as the first federal German head of government, Brandt visited the GDR for talks. The main principles of the social-liberal government's so-called 'new Ostpolitik' included:

- Renunciation of violence.

- Respect for the inviolability of European borders.

- Reduction of tensions.

- Securing peace.

- Good neighbourly relations.

- Co-operation across blocs.

- The agreement made by Egon Bahr with the Soviet Union in 1970 was crucial in this regard.

- The Moscow Treaty, signed in the Kremlin by Brandt and Scheel, paved the way for future Eastern treaties with Poland in 1970, the GDR in 1972, Czechoslovakia in 1973, and the Four-Powers Agreement in Berlin in 1971.

- Recognising the Oder-Neisse line as Poland's western border, the Federal Republic accepted the final loss of the former eastern German territories due to World War II.

- With his genuflection in Warsaw, which caused a worldwide sensation, Brandt admitted German guilt and responsibility for the Nazi regime's crimes. Willy Brandt, speaking for his country, asked for forgiveness. Through its new Ostpolitik, the Federal Republic established itself as a well-respected peace partner.

- The new Ostpolitik was highly divisive in domestic politics. The CDU and CSU opposition and the Vertriebenenverbände (exile organisations) intensely opposed the Eastern Accords.

- The SPD-FDP alliance respected Europe's political status quo while being committed to restoring German unification. Willy Brandt was a loyal supporter of Germans' right to self-determination. For him and his cabinet, full recognition of the GDR by the Federal Republic under international law remained a pipe dream.

- The two German states could not be foreign countries to one another, as Brandt pointed out.

- Developing ties between Bonn and East Berlin simplified intra-German travel, visits and mail traffic, resulting in significant improvements for millions of Germans.

- Ostpolitik shifted from a bilateral to a multilateral phase in 1973, with the start of talks on Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions (MBFR) and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE). The CSCE Final Act of Helsinki in 1975 is regarded as the pinnacle of international détente.

- The 35 European and North American signatory countries undertook to accept the inviolability of European borders, refrain from interfering in the domestic affairs of other countries, and respect human rights.

- FINAL ACT OF HELSINKI 1975. The Helsinki Process was a document signed after the third phase of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which took place in Helsinki, Finland, between 30 July and 1 August 1975.

- Willy Brandt and Egon Bahr believed that confidence-building measures and disarmament could lead to a new security system and, eventually, a European peace settlement. This hope, however, was yet to be realised in the 1970s. After 1975, the détente policy shifted into crisis mode.

SECOND PHASE OF OSTPOLITIK

- The East-West conflict was re-intensified due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the crisis in Poland between 1980 and 1981, and the superpowers' nuclear arms race at the start of the 1980s. Willy Brandt's key priority in the 'second Cold War' was averting a nuclear catastrophe, which would destroy everything.

- Beginning in 1983, the SPD and its chairman, who at that point were in the opposition in the Federal Republic, sought discussion with the communist rulers of the Eastern Bloc with more zeal. This second phase of Ostpolitik sought to reinvigorate détente, promote disarmament, and establish elements of a European peace settlement.

Mikhail Gorbachev - The Federal German Social Democrats negotiated nuclear and chemical weapons-free zones in Central Europe with the SED, the GDR's ruling communist party. However, the agreements that resulted were highly contentious. In the 1980s, Willy Brandt initiated high-level relations with communist parties in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union.

- Like his predecessor, Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, Brandt maintained tight ties with his successor, Mikhail Gorbachev, who took power in Moscow in 1985.

- Brandt warmly embraced and supported Gorbachev's disarmament and reform proposals.

OPPOSITION IN EASTERN EUROPE

- Willy Brandt took a cautious approach to the Eastern European civil rights movements that cited the CSCE Final Act and sought respect for human rights in their respective countries. On the one hand, he sympathised with the Czechoslovakian 'Charta 77' and the Polish labour union. On the other hand, he refused to meddle in the internal affairs of Eastern Bloc countries. Brandt avoided public support for opposition forces in order not to compromise his good relationships with government officials there.

- In the case of Poland, at the start of the 1980s, the SPD chairman feared a Soviet military invasion, like what happened in Czechoslovakia in 1968, for which he did not want to provide a reason. However, Brandt is widely criticised for reacting moderately to the imposition of martial law in 1981 and for failing to meet with Solidarno leader Lech Wasa during his visit to Poland in 1985.