Rosalind Franklin Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Rosalind Franklin to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early years

- Career and research

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Rosalind Franklin!

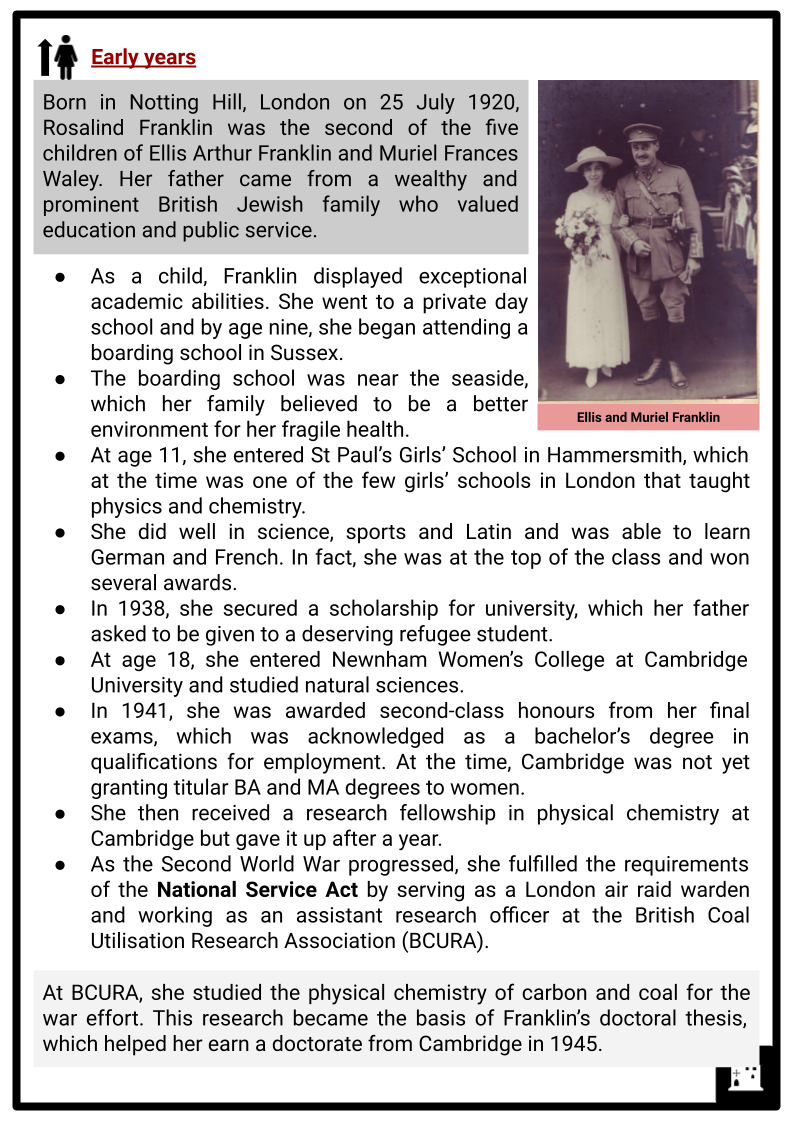

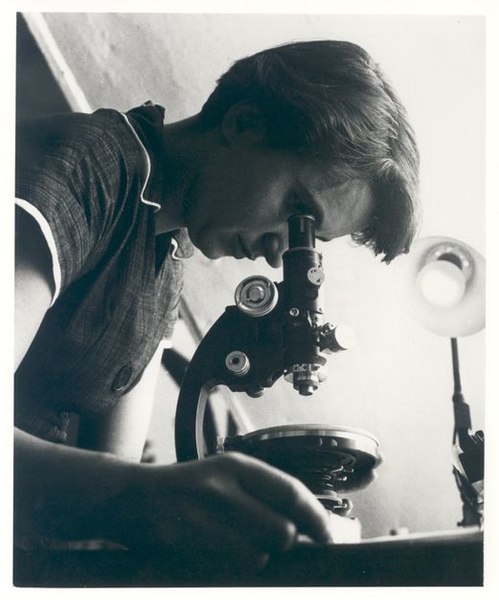

Born to a prominent British Jewish family, Rosalind Franklin received an excellent early education, which prepared her to pursue natural sciences at the university. She was an X-ray crystallographer and a chemist, whose work initially focused on carbon and coal. What was more well-known was her valuable contributions to the discovery of the molecular structure of DNA, which only earned wide recognition posthumously. Her pioneering research on the molecular structures of viruses was cut short when she died in 1958.

Early Years

- Born in Notting Hill, London on 25 July 1920, Rosalind Franklin was the second of the five children of Ellis Arthur Franklin and Muriel Frances Waley. Her father came from a wealthy and prominent British Jewish family who valued education and public service.

- As a child, Franklin displayed exceptional academic abilities. She went to a private day school and by age nine, she began attending a boarding school in Sussex.

- The boarding school was near the seaside, which her family believed to be a better environment for her fragile health.

- At age 11, she entered St Paul’s Girls’ School in Hammersmith, which at the time was one of the few girls’ schools in London that taught physics and chemistry.

- She did well in science, sports and Latin and was able to learn German and French. In fact, she was at the top of the class and won several awards.

- In 1938, she secured a scholarship for university, which her father asked to be given to a deserving refugee student.

- At age 18, she entered Newnham Women’s College at Cambridge University and studied natural sciences.

- In 1941, she was awarded second-class honours from her final exams, which was acknowledged as a bachelor’s degree in qualifications for employment. At the time, Cambridge was not yet granting titular BA and MA degrees to women.

- She then received a research fellowship in physical chemistry at Cambridge but gave it up after a year.

- As the Second World War progressed, she fulfilled the requirements of the National Service Act by serving as a London air raid warden and working as an assistant research officer at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA).

- At BCURA, she studied the physical chemistry of carbon and coal for the war effort. This research became the basis of Franklin’s doctoral thesis, which helped her earn a doctorate from Cambridge in 1945.

Career and research

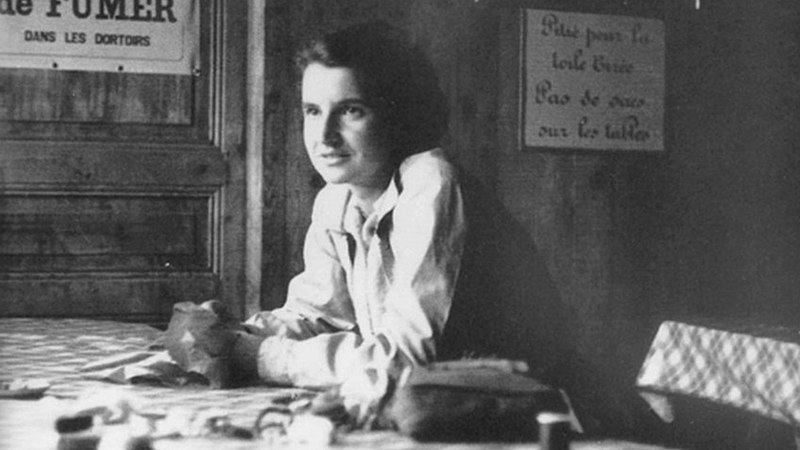

- With the war coming to an end, Franklin looked for job openings that would allow her to use her knowledge of coals. She was introduced to notable individuals that led to her appointment with the X-ray crystallographer Jacques Méring at the State Chemical Laboratory in Paris in 1947.

- In Paris, she learned the practical aspects of applying X-ray crystallography to amorphous substances.

- This resulted in her research on the structural changes caused by the formation of graphite in heated carbonaceous materials.

- She authored a number of papers based on this research, which proved valuable for the coking industry.

- In 1950, Franklin received a three-year fellowship to work at King’s College, London. However, she was delayed in finishing her work in Paris.

- In 1951, she joined as a research fellow in the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Biophysics Unit, which was directed by John Randall.

- She was initially assigned to work on X-ray diffraction of proteins and lipids in solution but was redirected to work on deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fibres and to guide the graduate student Raymond Gosling’s thesis, as the new developments in the field required her expertise.

- This reassignment caused significant friction between Franklin and another researcher, Maurice Wilkins, who had previously obtained a crystalline X-ray pattern of DNA and was very eager to continue the work.

- Both carried on their work in relative isolation, and their clashing personalities served to widen the gap.

What did Franklin’s X-ray diffraction work at King’s, College London discover?

- Franklin used X-ray diffraction to investigate the chemical makeup and structure of DNA, which remained unclear in the early 1950s.

- She used a new fine-focus X-ray tube and microcamera, which she refined to be humidity-controlling using different saturated salt solutions.

- This enabled her to produce better quality X-ray images, leading to her immediate discovery that the DNA sample could exist in two forms, what she called the crystalline or A form, and the paracrystalline or B form. This clear differentiation of A and B forms solved a problem that had baffled previous researchers.

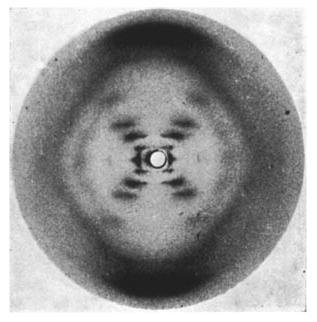

- In 1952, she and Gosling captured the image of the B form known as Photo 51, which later proved to be critical evidence in establishing the structure of DNA. However, Franklin put the photograph to the side as she focused on solving the diffraction pattern of the A form.

- Gosling later showed Photo 51 to Wilkins, who then showed it and some of Franklin’s unpublished data to James Watson, unbeknownst to Franklin.

- Using the characteristics and features of Photo 51, as well as evidence from other sources, Watson and Francis Crick developed a chemical model of the DNA molecule.

- In 1953, Franklin decided to transfer to Birkbeck College, as she was recruited by her former tutor, the physics department chair, John Desmond Bernal. This meant that she had to abandon her DNA work at King’s College, London.

- She left King’s College, London in mid-March, and her new laboratory was in one of a pair of deteriorated and cramped Georgian houses containing several different departments.

- She continued to help Gosling to finish his thesis. In July, the British scientific journal Nature published three papers showing the molecular structure of DNA to be a double helix, one of which was authored by Franklin and Gosling.

- At the end of 1954, she was granted funding from the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), allowing her to work as a senior scientist with her own research group.

- At Birkbeck College, Franklin’s expertise in X-ray crystallography was applied to explore ribonucleic acid (RNA), a molecule as fundamental to life as DNA.

- In particular, she studied the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), an RNA virus, in collaboration with Aaron Klug.

- She found out that all TMV particles were of similar length, and this first major work on TMV was published in Nature in 1955.

- She assigned the graduate student Kenneth Holmes to study the complete structure of TMV, and they soon made a discovery that the covering of TMV was protein molecules arranged in helices.

- Together with Klug and John Finch, they began publishing seminal works on TMV. The group proceeded to study RNA viruses affecting several plants.

- In 1956, Nature published Franklin’s study showing that the RNA in TMV was wound along the inner surface of the hollow virus.

- She travelled to the United States and visited the University of California, Berkeley. Her colleagues recommended that her group study another RNA virus, the poliovirus.

- Around this time, she was hospitalised multiple times and began undergoing treatment for ovarian cancer. Despite her illness, she continued to work.

- In 1957, her grant application was approved, and she was set to receive £10,000 for three years from the US Public Health Service of the National Institutes of Health.

- She intended to examine live, rather than killed, poliovirus at Birkbeck. Bernal arranged for the safe storage of the virus.

- Franklin, together with her group, set about to figure out the structure of the poliovirus while it was in a crystalline state.

- As their work progressed, she had to leave the research due to her rapidly deteriorating health.

- In early 1958, Franklin decided to return to work and was promoted to research associate in Biophysics. However, her health forced her to stop working. She died on 16 April.

- After her death, her team member Klug led the group research on the structure of the poliovirus.

- Franklin’s five-foot-high model of TMV was featured in Expo 58, the first major international fair after the Second World War, which opened in Brussels a day after she died.

- Throughout her career, she authored 19 papers on coals and carbons, five on DNA and 21 on viruses.

- In 1962, Watson and Crick, along with Wilkins, accepted the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery and description of the structure of DNA. Franklin’s role in the discovery went largely uncredited. Watson revealed in his memoir published in 1968 that it was Franklin who contributed to the crucial X-ray crystallography photograph.

- Several institutions honoured Franklin posthumously, including the Birkbeck, University of London opening the Rosalind Franklin Laboratory in 1997, the King’s College, London launching the Franklin-Wilkins Building in 2000, and the Finch University of Health Sciences in North Chicago, Illinois, changing its name to the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in 2004. Furthermore, in 2020, the UK Royal Mint released a 50-pence coin in honour of the 100th anniversary of Franklin’s birth, featuring a stylised version of Photo 51.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/Rosalind_Franklin.jpg/499px-Rosalind_Franklin.jpg?20180422194635

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Rosalind-franklin-in-paris.jpg/800px-Rosalind-franklin-in-paris.jpg?2022071909020

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/b/b2/Photo_51_x-ray_diffraction_image.jpg?20121230185027

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Rosalind Franklin?

Rosalind Franklin was a British biophysicist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was instrumental in understanding the structure of DNA.

- What was the significance of Rosalind Franklin's Photo 51?

Photo 51, an X-ray diffraction image of DNA taken by Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling, provided critical evidence for the helical structure of DNA. It was a key piece of data used by Watson and Crick in developing their double helix model.

- Did Rosalind Franklin receive recognition for her work on DNA?

Unfortunately, Rosalind Franklin did not receive significant recognition for her contribution to discovering the DNA structure during her lifetime. Credit for the discovery was primarily attributed to James Watson and Francis Crick.