Download Collectivisation

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Collectivisation to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Prelude to collectivisation

- Introduction of collectivisation

- Resistance to collectivisation and government’s response

- Outcomes of collectivisation

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Collectivisation!

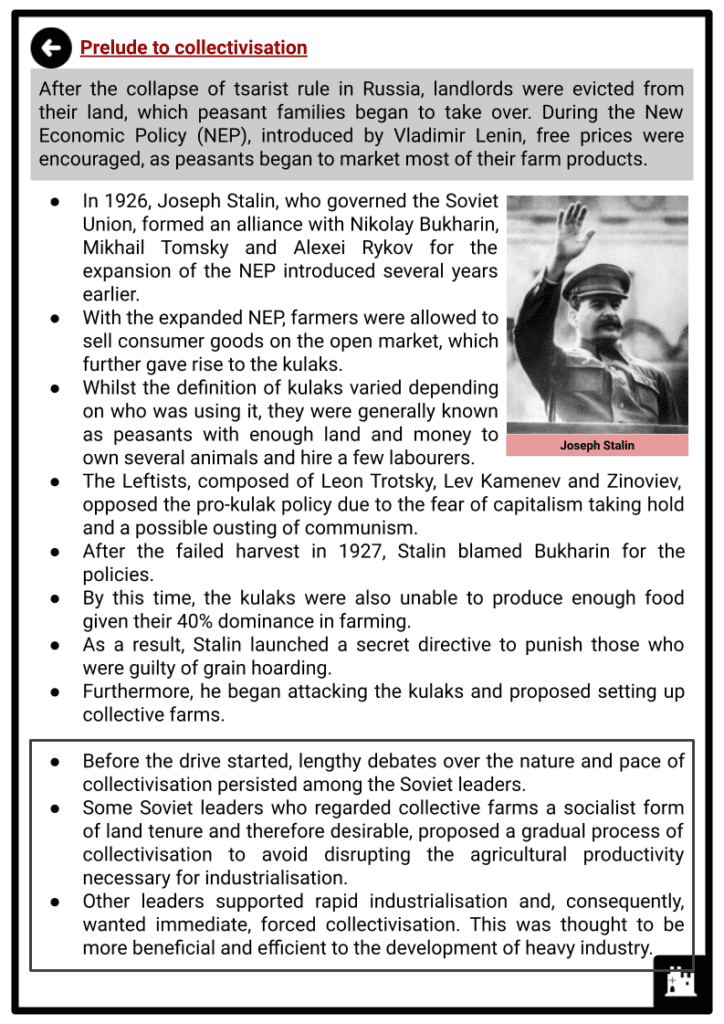

- Joseph Stalin supported economic and political policies which would modernise and bring prosperity to the Soviet Union, and collectivisation of agriculture was one of these. Under collectivisation, the peasantry was forced to give up their individual farms and join large collective farms known as kolkhozy. This was thought to transform the agricultural system with the collective farms put under complete state control. Stalin’s rigid policy led to more efficient farming and increased production at the expense of the kulaks and a widespread famine that killed millions.

Prelude to collectivisation

- After the collapse of tsarist rule in Russia, landlords were evicted from their land, which peasant families began to take over. During the New Economic Policy (NEP), introduced by Vladimir Lenin, free prices were encouraged, as peasants began to market most of their farm products.

- In 1926, Joseph Stalin, who governed the Soviet Union, formed an alliance with Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov for the expansion of the NEP introduced several years earlier.

- With the expanded NEP, farmers were allowed to sell consumer goods on the open market, which further gave rise to the kulaks.

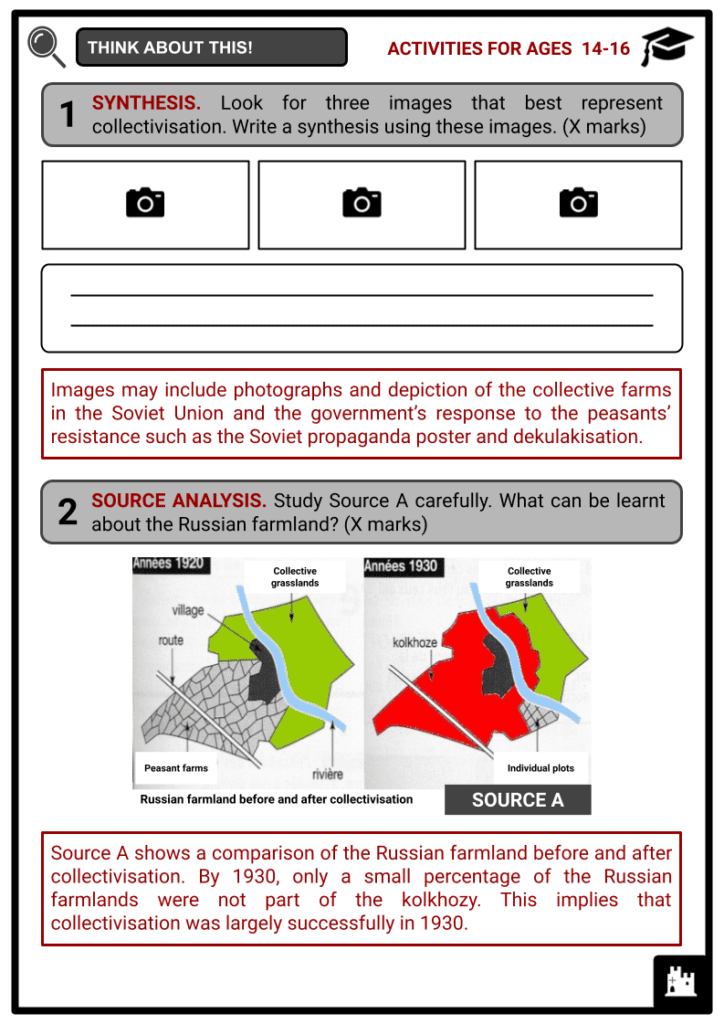

- Whilst the definition of kulaks varied depending on who was using it, they were generally known as peasants with enough land and money to own several animals and hire a few labourers.

- The Leftists, composed of Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Zinoviev, opposed the pro-kulak policy due to the fear of capitalism taking hold and a possible ousting of communism.

- After the failed harvest in 1927, Stalin blamed Bukharin for the policies.

- By this time, the kulaks were also unable to produce enough food given their 40% dominance in farming.

- As a result, Stalin launched a secret directive to punish those who were guilty of grain hoarding.

- Furthermore, he began attacking the kulaks and proposed setting up collective farms.

- Before the drive started, lengthy debates over the nature and pace of collectivisation persisted among the Soviet leaders.

- Some Soviet leaders who regarded collective farms a socialist form of land tenure and therefore desirable, proposed a gradual process of collectivisation to avoid disrupting the agricultural productivity necessary for industrialisation.

- Other leaders supported rapid industrialisation and, consequently, wanted immediate, forced collectivisation. This was thought to be more beneficial and efficient to the development of heavy industry.

Introduction of collectivisation

- Among Stalin’s major goals for the Soviet Union, he aimed to achieve economic prosperity. In order to achieve this, he supported economic and political policies which would modernise the country, and collectivisation was one of these. Stalin specifically wanted to drive the Soviet Union ahead of other countries in Western Europe, as well as the United States.

- Why collectivise the agriculture of the Soviet Union?

- Soviet agriculture at the time was carried on by primitive methods mostly on very small holdings, therefore inefficient.

- Food was needed for workers in the towns. This was essential if Stalin’s Five-Year Plans were to succeed.

- The NEP appeared to be failing. In fact, the Soviet Union was 2-million-ton of grain short to feed the towns in 1928.

- As part of the industrialisation and modernisation of the Soviet Union, peasants needed to migrate to work in the towns.

- Peasants were expected to grow cash crops that could be exported to raise money in order to acquire foreign machinery.

- The kulaks were regarded as capitalists who liked their private wealth. They were also influential, and led peasant opinion.

- The maintenance of private ownership of the means of production was incompatible with the system of socialist economy that the Communists wanted to install in the Soviet Union.

Key features of collectivisation

What?

- Collectivisation was Stalin’s policy that initially encouraged the transformation of agriculture from private-capitalist to collective-socialist production. Under collectivisation, the peasantry was forced to give up their individual farms and join large collective farms known as kolkhozy.

How?

- In order to modernise agriculture, small farms were combined into one and used up-to-date agricultural methods and machinery to boost productivity. All products were sold to the government and farmers received wages.

When?

- In 1927, the Communist Party decided to undertake collectivisation at a gradual pace, allowing the peasantry to join kolkhozy voluntarily.

- In 1928 and 1929, the Central Committee authorised plans that increased the goals and demanded 20% of the nation’s farmland to be collectivised by 1933. The kulaks resisted this strongly.

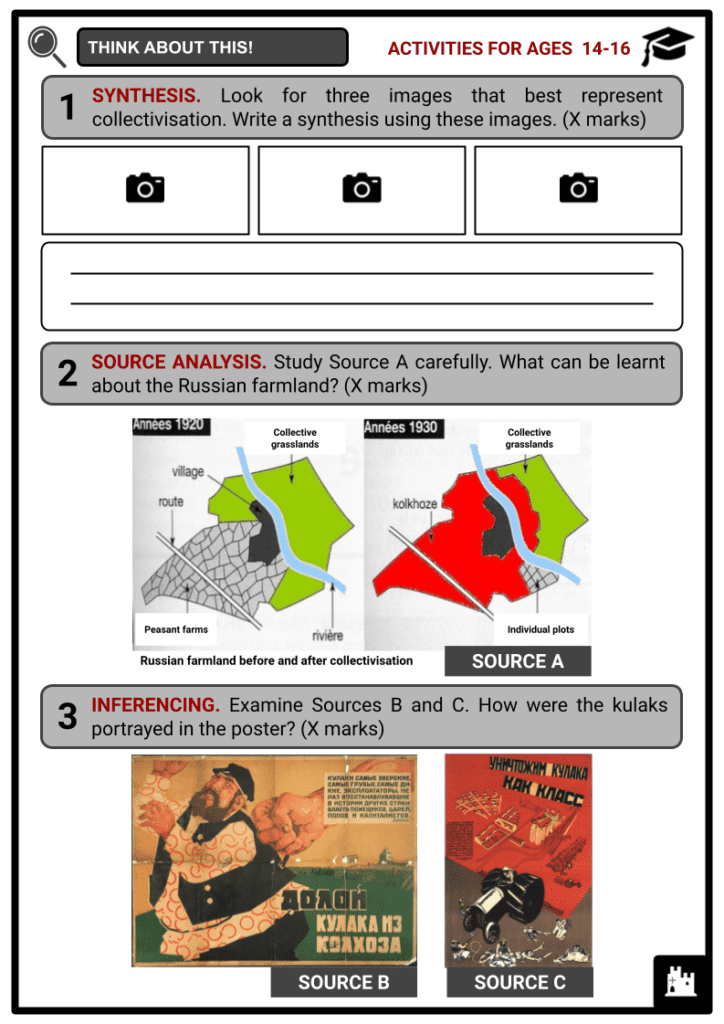

- Between October 1929 and January 1930, the proportion of peasant households forced into kolkhozy shot up from about 4% to 21%, although the government’s main efforts in the rural area were focused on extracting grain from the kulaks.

- During the winter of 1929-30, compulsory collectivisation was enforced by the army. Stalin called upon the party to “liquidate the kulaks as a class”. The Central Committee decided that a huge majority of the peasant households should be collectivised by 1933. Peasants who resisted the policy were punished harshly.

Harsh measures included:

-

- Land confiscations

- Arrests

- Deportations to prison camps

- As a result, by March 1930 about 58% of the peasantry had been forced to join collective farms.

- Due to fears that the kulaks would try to undermine the scheme, the kulaks themselves were disallowed to join these collective farms.

- Consequently, an estimated five million kulaks were deported to Central Asia or to the timber regions of Siberia, where they were used as forced labour. Approximately 25% of these died by the time they reached their destination.

Resistance to collectivisation and government’s response

- In 1930, many peasants rebelled against Stalin’s policy and objected violently to abandoning their private farms. In many cases, they burned farmland, destroyed their equipment and slaughtered their livestocks.

- About 2,200 rebellions involving more than 800,000 peasants broke out in several regions during 1930.

- As the animosity toward the Soviet regime became so great, Stalin was forced to call a halt to collectivisation.

- In March 1930, he wrote an article “Dizzy from Success” for Pravda, in which he claimed that 55% of Soviet agricultural households were working in collective farms. Furthermore, he shifted the blame to local officials for being overzealous in their duties.

- Stalin did not reveal the resistance to collectivisation of peasant communities in Ukraine, the north Caucasus and central Asia. Whilst the risings were suppressed by the army, widespread resentment led to a decline of productivity.

- The hiatus in the collectivisation process resulted in a decrease in percentage of peasant households enrolled in kolkhozy: only about 24% remained in June 1930.

- Similarly, in the southwestern region the figure fell from 82% in March to 18% in May.

- Later that year, the drive was renewed at a slower pace but with equal tenacity.

- With the enforcement of various administrative pressures, one-half of the peasant-households were recollectivised by 1931.

- The absence of heavy agricultural machinery and farm animals impaired the new collective farms, causing a decline in output.

- In 1932-33, a crop failure spread a famine in the countryside, leading to the deaths of millions of peasants.

- By 1939, 99% of Soviet farmland was collectivised, and 90% of all production went to the government.

Outcomes of collectivisation

- The Soviet government achieved some successes imposing the collectivisation of agriculture, but the cost to the Soviet people was immense. Nevertheless, the Communist programme persisted in spite of the cost in human suffering and lives.

Successes of the policy

- Internal passports were introduced, which controlled peasants moving between rural or urban areas in search of food.

- Peasant farmers were taught basic literacy on collective farming and were granted private plots of land.

- Motor Tractor Stations were set up near kolkhozy, which provided communal access to equipment, including tractors and harvesters.

- Grain production increased to about 100 million tons in 1937, and 99% of farmland was collectivised by 1939.

Failures of the policy

- Many peasants protested through passive resistance. They began to slaughter animals to avoid confiscation, which resulted in supply shortages.

- Under dekulakisation, Stalin’s policy to eradicate the kulaks as a class, around 5 million people suffered.

- The peasants’ resistance to Stalin’s rigid policy and a harvest failure were followed by widespread and severe famine known as the Great Famine in 1932-33.

- Despite these great costs, the intense collectivisation brought about the final establishment of Soviet power in the countryside. Agriculture became integrated with the rest of the state-controlled economy. Moreover, the state was endowed with the capital it needed to transform the Soviet Union into a major industrial power.