Russification Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Russification to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Crimean Tatars and Russification

- Types of Russification

- Russification under the Tsars

- Russification under the Soviets

- Ukraine’s Russification throughout history

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Russification!

Policies intended to propagate Russian culture and language among non-Russians are called Russification. These programmes first appeared in the late 18th century, but their prominence began in the 1860s. In a historical context, the phrase refers to official and unofficial practices of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union towards its national constituents and minorities in Russia, all of which were intended to establish Russian dominance and hegemony.

CRIMEAN TATARS AND RUSSIFICATION

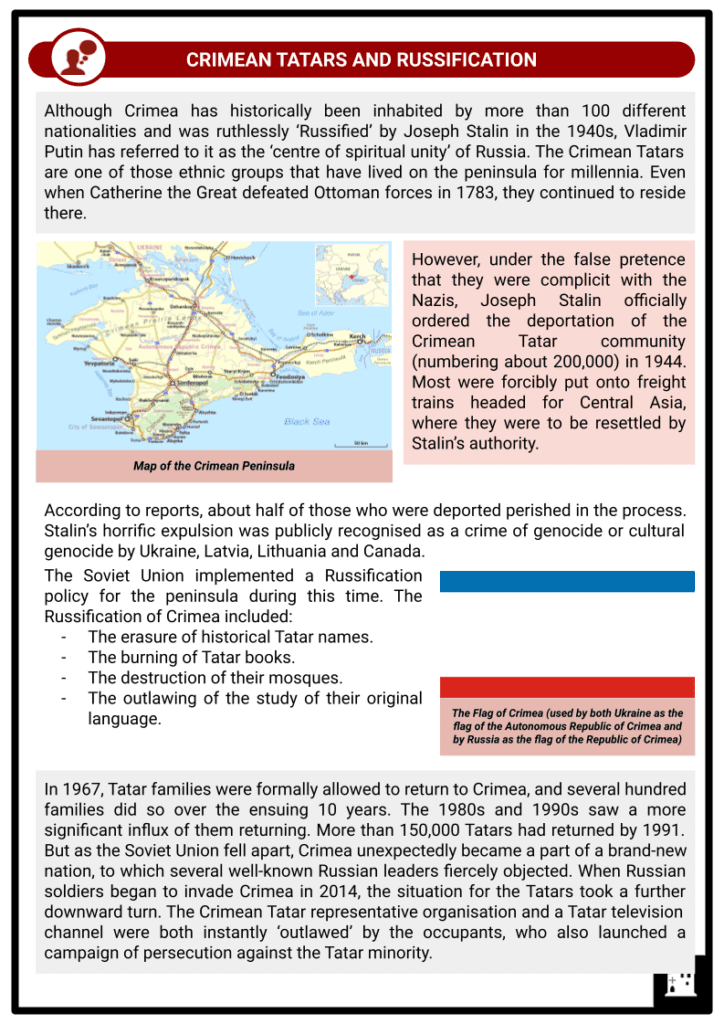

- Although Crimea has historically been inhabited by more than 100 different nationalities and was ruthlessly ‘Russified’ by Joseph Stalin in the 1940s, Vladimir Putin has referred to it as the ‘centre of spiritual unity’ of Russia. The Crimean Tatars are one of those ethnic groups that have lived on the peninsula for millennia. Even when Catherine the Great defeated Ottoman forces in 1783, they continued to reside there.

- However, under the false pretence that they were complicit with the Nazis, Joseph Stalin officially ordered the deportation of the Crimean Tatar community (numbering about 200,000) in 1944. Most were forcibly put onto freight trains headed for Central Asia, where they were to be resettled by Stalin’s authority.

- According to reports, about half of those who were deported perished in the process. Stalin’s horrific expulsion was publicly recognised as a crime of genocide or cultural genocide by Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania and Canada.

- The Soviet Union implemented a Russification policy for the peninsula during this time. The Russification of Crimea included:

- The erasure of historical Tatar names.

- The burning of Tatar books.

- The destruction of their mosques.

- The outlawing of the study of their original language.

- In 1967, Tatar families were formally allowed to return to Crimea, and several hundred families did so over the ensuing 10 years. The 1980s and 1990s saw a more significant influx of them returning. More than 150,000 Tatars had returned by 1991. But as the Soviet Union fell apart, Crimea unexpectedly became a part of a brand-new nation, to which several well-known Russian leaders fiercely objected. When Russian soldiers began to invade Crimea in 2014, the situation for the Tatars took a further downward turn. The Crimean Tatar representative organisation and a Tatar television channel were both instantly ‘outlawed’ by the occupants, who also launched a campaign of persecution against the Tatar minority.

TYPES OF RUSSIFICATION

- According to Edward C Thaden, a Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois, there are three types of Russification: unplanned, administrative and cultural.

- Thaden used the term unplanned Russification to refer to natural, cultural assimilation processes by which some people or groups adopt the Russian language and frequently the Russian Orthodox faith.

- Administrative Russification, which is frequently difficult to distinguish from centralisation, refers to official policies like those that mandate the use of Russian throughout all government departments.

- The attempt to integrate entire communities and replace their native culture with Russian is known as cultural Russification.

- While rare during the imperial era, cultural Russification became increasingly popular under the Soviets. Russian nationality policy, however, incorporated both unplanned and administrative Russification.

RUSSIFICATION UNDER THE TSARS

- Individualised unplanned Russification started early in the Moscow period. The reputation of Russian culture expanded along with Muscovite strength, especially following the capture of Kazan, the capital of the Tatars, in 1552, increasing its allure to non-Russians.

- Moscow pushed its new subjects to convert to Russian Orthodoxy, but these initiatives could have been more persistent and vigorous. Only around the middle of the 18th century was a concentrated effort made to convert Muslims and Animists in the Volga region. Due to this programme, many Tatars and almost all Mordvins, Chuvash and Votyaks converted.

- Particularly in the regions won for Russia by its wars against the Turks and through the partition of Poland, Catherine the Great pushed administrative Russification forward. Catherine did not, however, anticipate the cultural Russification of the inhabitants of this region. Instead, she sought to tie these recently acquired estates to Saint Petersburg by rationalising their management. Even here, her achievements were reasonably modest.

A satire on Catherine’s morals and on the Russo-Turkish war, from 1791 - During the rule of Tsar Nicholas I, policies approximating cultural Russification first appeared. The idea of formal nationality is crucial in this context. This worldview was developed by Sergei Uvarov, Nicholas’ minister of education, and is briefly stated as ‘orthodoxy, autocracy and nationality’.

- Uvarov sought to establish a contemporary Russian country that was unified in its fidelity to the monarch, shared the moral principles of Russian Orthodoxy, and spoke Russian.

- Official nationalism would seem to be a glaring example of cultural Russification, with non-Russian cultures being wholly assimilated. As nationality was the third and last component of his tripartite formula, Uvarov was more interested in promoting dynastic patriotism and morality.

- The Poles and the Jews were two of the most complex ethnic groups in Imperial Russia. The Poles had significant autonomy in the Kingdom of Poland from 1815 until 1830. This autonomy was significantly diminished following the Polish rebellion of 1831, but Saint Petersburg started implementing cultural Russification tactics in a second uprising in 1863.

- The educational system did not wholly outlaw Polish, but imported Russian teachers set the standard. In any case, private education was not allowed in Polish. Although Russian policies contributed to the high percentage of illiteracy among Poles, Polish culture flourished throughout these decades despite all constraints. Jews seemed to be a foreign religious and cultural group in official Russia. Throughout the 19th century, several initiatives tried to modernise the Jewish community or, to put it another way, make Jews more like educated Russians.

- These actions had less effect, partly because Jews often saw them as little more than fronts for religious conversion. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that a sizeable and quickly expanding community of Russian Jews emerged. It’s possible to view these Jews’ acceptance of Russian culture as one of the rare successes of the Russification process.

- Before the 20th century, few Russians separated Belarusians and Ukrainians as distinct national entities. The majority of these two East Slavic ethnic groups were Orthodox, and they spoke languages that were typically considered to be merely Russian dialects. Russian was frequently a language that students in Ukrainian and Belarusian schools could not understand. Belarusians and Ukrainians weren’t free to publish or teach in their native tongues until after 1905.

- The Russian Empire captured large tracts of land in Central Asia in the 19th century. In this area, administrative Russification was practised, and schools for native children were established. Towards the end of the century, the younger, educated Muslim generation, particularly Tatars, developed an interest in the Russian language.

RUSSIFICATION UNDER THE SOVIETS

- Officially, the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, explicitly repudiated all forms of national prejudice, including Russification. In practice, the situation was more complicated. Lenin’s insistence on a highly centralised party had already led to clashes with Jewish socialists (the Bund).

- The Bolsheviks opposed harsh measures used against non-Russians and backed national self-determination. They consequently criticised bourgeois nationalism without delay. After 1917, despite several initiatives to promote the growth of national (i.e., non-Russian) cultures, party centralisation meant that anyone hoping to go to the top of the Soviet hierarchy had to speak Russian well and embrace a lot of Russian-Soviet cultural norms. The patronymics and surnames used by communist militants in Central Asian Muslim nations are one illustration of this.

- Upon seizing power in late 1917, the Bolsheviks quickly issued a Declaration to the Peoples of Russia, pledging an end to any national or religious discrimination, guaranteeing free cultural development, and even endorsing national self-determination.

- The civil war brought Ukraine, the Caucasus and Belarus back under Moscow’s control. The Soviet Constitution of 1924 set out a seemingly federal but highly centralised state structure. As its name implied, the USSR consisted of individual Soviet Socialist Republics, all of which officially had the right to secede from the Union.

- Administrative Russification was practically complete throughout the Soviet era: all official documents, including passports, postal forms and stamps, were printed in Russian or, in union republics, in Russian and the republican language, such as Latvian. Some of the administrative Russification that took place included:

- Fluency in speaking the Russian language

- Incorporation of Russian material within the USSR

- Mixed marriage between a Russian and other nationalities

- In the Russian Republic, several smaller nationalities mainly saw significant rates of Russification, leading post-Soviet national leaders to lament the widespread de-nationalisation of their people under Soviet authority, for instance, in Tatarstan.

- Culture-wise, things were more complex. All students from Tallinn to Vladivostok studied Russian in school starting at a young age, even though non-Russian republics did have their schools employing their tongues. Even Estonian television transmitted the Russian-language Moscow news programme Vremya every evening. Radio and television programmes were available in a variety of languages.

- Numerous, if not hundreds, of so-called Soviet languages were used in publications, and students were permitted to study in their union republic’s speech up to and including the university level. However, even by students in Vilnius, Baku or Kyiv, all dissertations at the kandidat (Master’s or PhD degree) were written in Russian.

- Even obtaining a primary education in the local language was only sometimes straightforward in the Belarusian and Ukrainian republics. Parents who insisted too much ran the risk of being branded as nationalist or anti-Soviet.

UKRAINE’S RUSSIFICATION THROUGHOUT HISTORY

- The Ukrainian People’s Republic declared complete independence in response to the Bolshevik takeover of power on 7 November 1917, claiming the central Ukrainian provinces and the traditionally Ukrainian settled territories of Kharkiv, Odesa and the Donets River Basin. More significantly, however, the Central Rada refused to cooperate with the new government in Petrograd.

- Lenin went out of his way to accept the Ukrainian nation as separate in June 1917 and considered the Rada a potential collaborator in his attack on the Provisional government. Still, his attitude significantly shifted following the Bolshevik takeover of power. To gain a majority at the Congress of the Soviets, the Bolsheviks attempted to apply the same strategy they had used to seize power in Petrograd in Kyiv. Nevertheless, they failed and fell into the minority. After the Bolsheviks moved to Kharkiv, a bustling industrial city closer to the Russian border, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was created. The Central Rada refused to acknowledge or accept the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic because it viewed it as a ‘Bolshevik clone’.

- The western countries, who supported Denikin and his anti-Bolshevik campaign, tried to contain the ‘anti-Ukrainian zeal of Volunteer Army Commanders’ when Ukrainian complaints about their treatment and the violation of their civil liberties and cultural rights reached them.

This 1921 Soviet recruitment poster for military education featured the Ukrainisation theme - Because of the Bolshevik programme of Korenisation, Ukrainian culture was revitalised after World War One. The approach opposed the idea of Soviet people with common Russian ancestry, even though it was intended to increase the Party’s influence among local cadres. Stalin put the concept of a united Soviet Union, in which competing national cultures were no longer permitted, ahead of Korenisation. The Russian language grew increasingly into the sole official tongue of Soviet socialism.

- An extensive campaign against ‘nationalist deviation’ was launched during agricultural reorganisation and industrialisation, which resulted in Ukraine’s Korenization strategy being abandoned and the political and cultural elite being attacked. The first round of purges, between 1929 and 1934, was directed against the Party’s revolutionary generation, which included many Ukrainisation proponents in Ukraine.

‘By the mid-1930s, with purges in some of the national areas, the policy of korenizatsiia took a new turn, and by the end of the 1930s, the policy of promoting local languages began to be balanced by greater Russianization, though perhaps not overt Russification or attempts to assimilate the minorities,’ writes Vernon V Aspaturian in his book The Non-Russian Peoples.

- Mykola Skrypnyk, the Ukrainian commissar of education, was explicitly singled out by the Soviet government for advocating modifications to the Ukrainian language that were deemed risky and counterrevolutionary.

- Russia has been working harder since 2022 to ‘Russify’ the parts of Ukraine under its control. Since President Vladimir Putin began his full-scale invasion of the nation on 24 February 2022, Russian soldiers have taken a large portion of Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk and its southern Kherson and Zaporizhzhia provinces. There are now more and more indications that the head of the Kremlin is attempting to ‘Russify’ these areas to transform them into Russian regions.

- The Crimean Peninsula, which Russia brutally took from Ukraine in 2014, is accessible from Kherson, one of Ukraine’s southernmost provinces, a vital area with a sizable agriculture industry that touches both the Black and Azov Seas. Iron mines and big manufacturing firms may be found in Zaporizhzhya, a significant industrial hub. Together, they were occupied and assisted Russia in creating a land bridge from the mainland to Crimea.

- Russian actions have caused major fears, even though there was evidence of Russification and Russia’s slow annexation of these lands for weeks since the invasion began. Firstly, Putin issued a rule that would make it easier for Ukrainians living in seized territory to ‘passportise’, or become Russian citizens. The Ukrainian Foreign Ministry denounced Russian efforts as ‘a gross violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, norms and principles of international humanitarian law,’ and the EU ambassador to Ukraine, Matti Maasikas, claimed that they are taking place because the local Ukrainian population is not supporting them.