Soweto Uprising Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Soweto Uprising to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Reasons for the Uprising

- Soweto Uprising

- Aftermath of the Uprising

- International Reactions

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Soweto Uprising!

The Soweto Uprising was a high school student-led protest in Soweto, South Africa on 16 June 1976. The protest responded to the introduction and, later on, use of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in local schools. An estimated 20,000 students joined the protests. Students protested the use of Afrikaans in local schools that served Black students because it was a language of the White minority that ruled South Africa. The introduction of Afrikaans triggered the majority of Black students because, at that time, the apartheid system, which called for racial segregation, had been implemented by the South African government.

REASONS FOR THE UPRISING

- The Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974 was a policy that forced all schools that accepted and served Black students to use Afrikaans and English in equal amounts as their language of instruction and communication. It is crucial to know that, because of the apartheid system in South Africa, the Black students denied this policy and preferred English over Afrikaans.

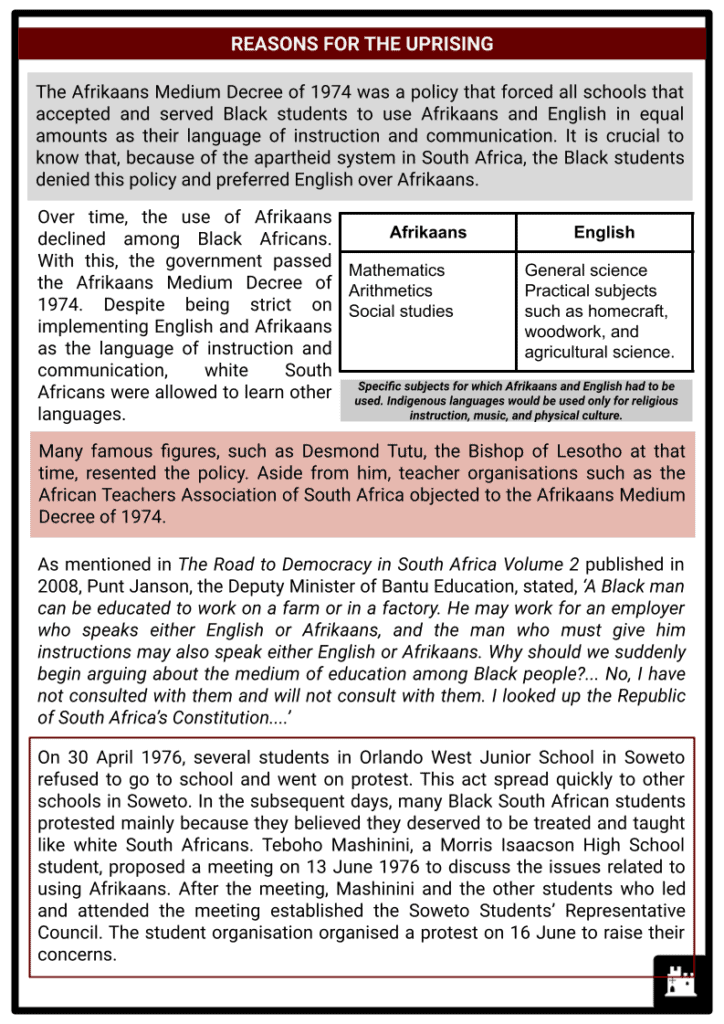

- Over time, the use of Afrikaans declined among Black Africans. With this, the government passed the Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974. Despite being strict on implementing English and Afrikaans as the language of instruction and communication, White South Africans were allowed to learn other languages.

- Afrikaans. Mathematics, Arithmetics, Social studies

- English. General science, Practical subjects such as homecraft, woodwork, and agricultural science.

Specific subjects for which Afrikaans and English had to be used. Indigenous languages would be used only for religious instruction, music, and physical culture.

- Many famous figures, such as Desmond Tutu, the Bishop of Lesotho at that time, resented the policy. Aside from him, teacher organisations such as the African Teachers Association of South Africa objected to the Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974.

- As mentioned in The Road to Democracy in South Africa Volume 2 published in 2008, Punt Janson, the Deputy Minister of Bantu Education, stated, ‘A Black man can be educated to work on a farm or in a factory. He may work for an employer who speaks either English or Afrikaans, and the man who must give him instructions may also speak either English or Afrikaans. Why should we suddenly begin arguing about the medium of education among Black people?... No, I have not consulted with them and will not consult with them. I looked up the Republic of South Africa’s Constitution....’

- On 30 April 1976, several students in Orlando West Junior School in Soweto refused to go to school and went on protest. This act spread quickly to other schools in Soweto. In the subsequent days, many Black South African students protested mainly because they believed they deserved to be treated and taught like white South Africans. Teboho Mashinini, a Morris Isaacson High School student, proposed a meeting on 13 June 1976 to discuss the issues related to using Afrikaans. After the meeting, Mashinini and the other students who led and attended the meeting established the Soweto Students’ Representative Council. The student organisation organised a protest on 16 June to raise their concerns.

SOWETO UPRISING

- An estimated 20,000 Black students walked from their schools to Orlando stadium on 16 June 1976 to protest having to learn Afrikaans in their school. The Soweto Students’ Representative Council organised the protest and had support from the Black Consciousness Movement, a grassroots anti-apartheid movement that was established in the mid-1960s in South Africa.

- Some faculties and school staff joined the protest to support their students. The organisers wanted a peaceful protest since most participants were students, but to their surprise, police barricades blocked the streets of their intended route. Due to this, students began to chant and wave their placards.

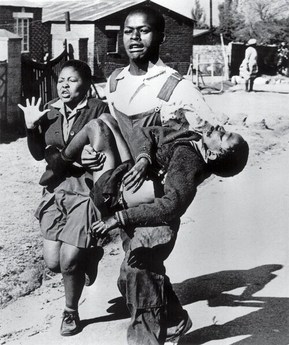

- Shortly after the students waved their placards, the police started shooting them. Hastings Ndlovu, 15, and Hector Pieterson, 12, were among the first kids killed when they were shot. The photographer Sam Nzima captured a dying Hector Pieterson being carried away by Mbuyisa Makhubo and escorted by Hector’s sister, Antoinette Pieterson, in a shot symbolising the Soweto Uprising.

Makhubo carrying Hector Pieterson who had been shot by South African police during the Soweto Uprising. - The police continued shooting at the demonstrators. The violence worsened as bottle shops and beer halls were targeted as apartheid government outposts and state-run outposts. By nightfall, the fighting had subsided. Throughout the night, police vans and armoured vehicles patrolled the streets.

- The hospitals were flooded with bruised and bloodied children. The authorities asked the hospitals for a list of all casualties with bullet wounds so that they might charge them with rioting. The hospital administration forwarded the request to the doctors, who declined to create the list.

- On 17 June, heavily armed police officers were deployed to Soweto. They carried weapons, including automatic rifles, stun guns, and carbines. They patrolled the area in armoured vehicles, with helicopters hovering overhead. The South African Army was also alerted as a tactical move to demonstrate military force.

AFTERMATH OF THE UPRISING

- The rebellion represented the government’s most serious challenge to apartheid. The growing worldwide boycott aggravated the economic and political upheaval it produced. The apartheid government would never be able to restore the relative calm and social stability in the early 1970s as Black resistance increased. Liberation movements that had been crippled or banished acquired new traction when new recruits joined the anti-apartheid movement.

- The government’s actions in Soweto infuriated many white South Africans. The day following the massacre, approximately 400 White students at the University of the Witwatersrand marched through Johannesburg’s city centre to protest the killing of children.

- Black workers joined in with the strike as the campaign continued. Riots erupted in other South African cities’ Black townships. Student associations channelled the youth’s rage and enthusiasm into political resistance.

- In the following days, many students from different schools across Soweto protested due to the government’s violent response to the protest on 16 June.

- When the death rate had risen to over 600 by the end of 1976, most of the protests had subsided. The conflicts in Soweto created economic instability. The South African rand, the official currency of the Southern African Common Monetary Area rapidly depreciated, plunging the government into a crisis.

INTERNATIONAL REACTIONS

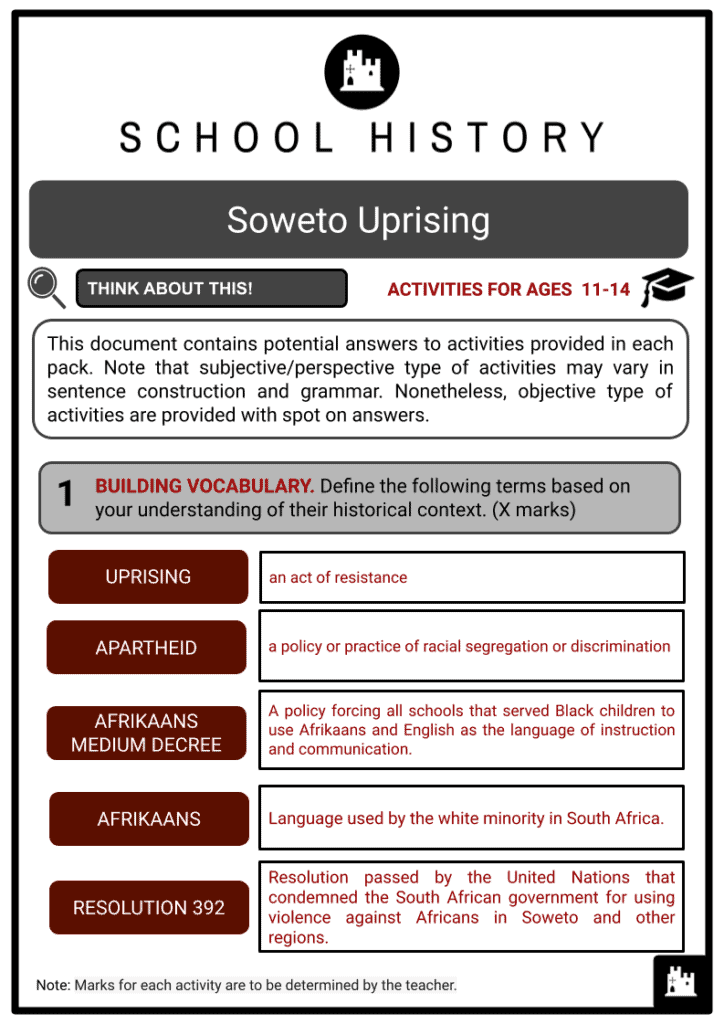

- The United Nations Security Council voted Resolution 392, sharply condemning the incident and the apartheid administration. The United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met John Vorster, the South African State President, a week after the uprising began. Instead of discussing the incident in Soweto, they talked about other political issues concerning their territories.

- Exiles of the African National Congress (ANC), a social-democratic political party in South Africa, condemned the incident in Soweto and called for international action and more economic sanctions against South Africa.

Photograph showing the students protesting in front of police during the protest against Afrikaans - Images of the rioting were broadcast throughout the world, shocking millions of viewers. The photograph of Hector Pieterson’s lifeless body, taken by photojournalist Sam Nzima, sparked outrage and led to widespread condemnation of the apartheid regime. In June 1996, the Ulwazi Educational Radio Project of Johannesburg created an hour-long radio documentary depicting the events of 16 June totally from the perspective of those living in Soweto at the time, 20 years after the uprising.

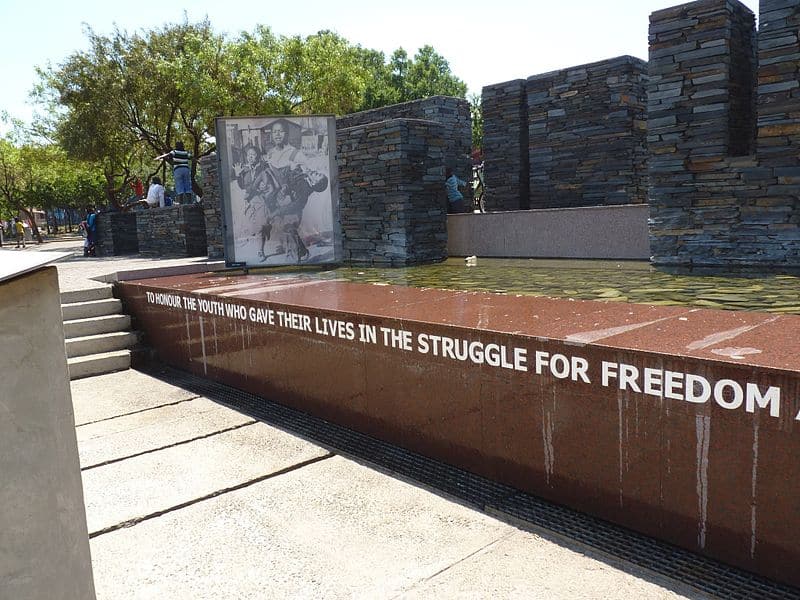

- In South Africa, 16 June is now observed annually as Youth Day, commemorating the uprising. Across the African continent, it is regarded as the Day of the African Child, which not only marks the uprising but also focuses on children in Africa – celebrating their lives and noting the challenges they regularly face.

KEY FACTS

- The Black South African teenagers who demonstrated that day came from several high schools in Soweto.

- Apartheid’s objective was to elevate the Afrikaans language and culture above all other cultures in South Africa. Remember that Afrikaans comprised only a minor percentage of South Africa’s population. Before establishing language limits in the schools, the Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974 neglected to obtain the input of significant stakeholders in the Black community.

- In South Africa, Hector Pieterson, a 13-year-old who was cowardly shot and killed by police during the revolt, is widely regarded as a martyr. There is also a memorial to him near where he was killed. Pieterson was with his older sister, Antoinette Pieterson, at the time of his death.

- The famous anti-apartheid activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu once called Afrikaans ‘the language of the oppressor’.

SOWETO IN POPULAR MEDIA

- Cry Freedom, a 1987 film directed by Richard Attenborough, and Sarafina!, a 1992 musical film, both featured the Soweto Uprising.

- The uprising was also depicted in the 2003 film Stander, which was based on the life of legendary bank robber and former police captain Andre Stander. Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba’s song Soweto Blues described the Soweto Uprising and the role of children in it.