Thabo Mbeki Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Thabo Mbeki to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life and Education

- Early Career

- Rise to Presidency

- HIV/AIDS Denialism

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Thabo Mbeki!

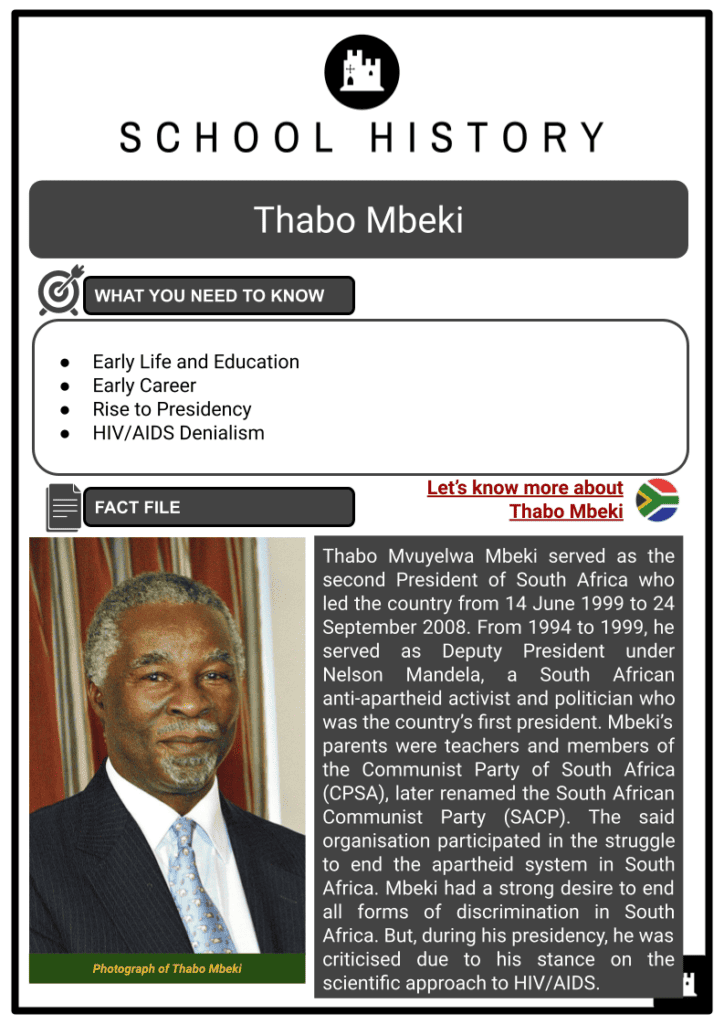

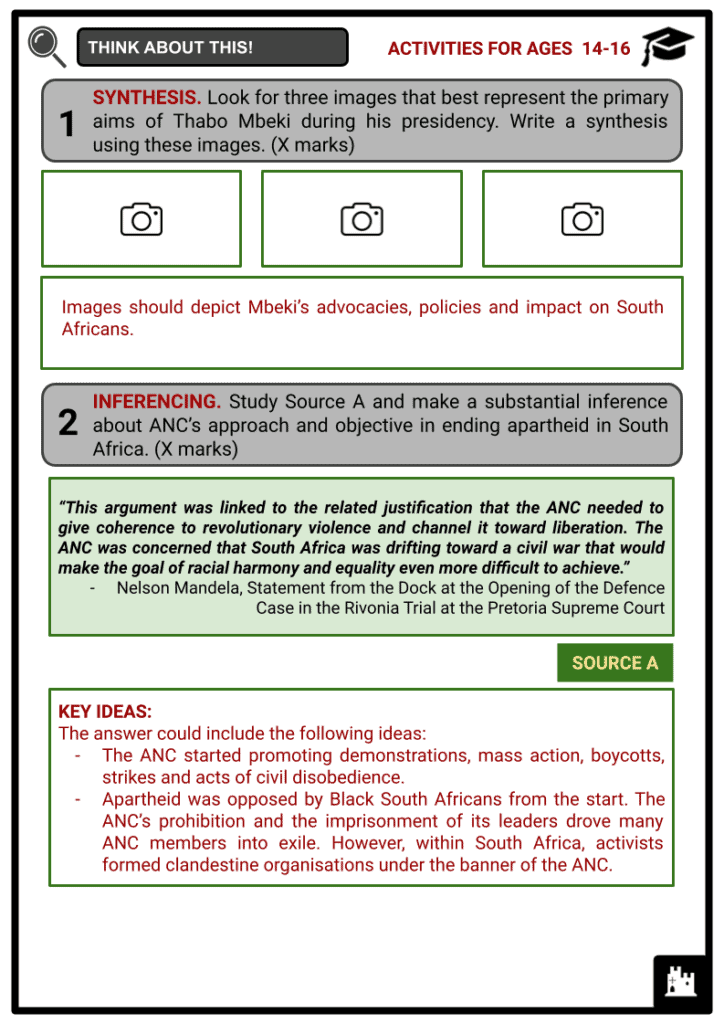

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki served as the second President of South Africa who led the country from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008. From 1994 to 1999, he served as Deputy President under Nelson Mandela, a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician who was the country’s first president. Mbeki’s parents were teachers and members of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), later renamed the South African Communist Party (SACP). The said organisation participated in the struggle to end the apartheid system in South Africa. Mbeki had a strong desire to end all forms of discrimination in South Africa. But, during his presidency, he was criticised due to his stance on the scientific approach to HIV/AIDS.

EARLY LIFE AND EDUCATION

- Mbeki was born on 18 June 1942 in Mbewuleni, located in the Sakhisizwe Local Municipality of the Eastern Cape in South Africa. Mbeki was the second of four siblings: he had one sister and two brothers. His parents were Nomaka Epainette Mbeki and Govan Mbeki.

- At an early age, Mbeki’s family was separated from Govan due to a teaching assignment outside their hometown. Mbeki recalled that he grew up seeing portraits of famous figures such as Karl Marx and Mahatma Gandhi all over their house. The two became known for their philosophical perspectives on social classes and how society could provide more for the masses.

- Mbeki began his studies in 1948. Towards the end of his education, the Bantu Education Act was implemented, which later became the Black Education Act. This act was a form of segregation law that legalised several aspects of the apartheid system.

- At 14, he became a member of the Youth of League, a youth wing organisation of the African National Congress (ANC), which is known as a social democratic party in South Africa. Since then, he has been active on issues concerning student politics.

- In 1959, a strike happened that interrupted Mbeki’s schooling at Lovedale. After that, he transferred to Johannesburg, where he became the guide of Walter Sisulu and Duma Nokwe. Both figures were South African anti-apartheid activists and held positions in the ANC.

- Mbeki was very active in participating and organising student protests. His activities resulted in his expulsion from Lovedale. Despite this, he continued his studies at home. Also, Mbeki remained active in the ANC even after the organisation was banned in South Africa.

- While finishing his British A Levels, Mbeki was elected Secretary of the African Students’ Association (ASA). The ASA was established on 17 December 1961 in Durban under the ANC. When the ASA was formed, Durban was considered the centre of Black student life in South Africa. Unfortunately, years after Mbeki joined the ASA, the organisation collapsed due to the continuous arrest of many of its members. The arrest occurred when political movements were coming under increasing attack from the state.

EARLY CAREER

- Mbeki took a degree at the University of Sussex due to the encouragement of the ANC. During this period in Mbeki’s life, many student activists fled South Africa because of police attention. While at university, he was involved in many ANC activities and immersed himself in the organisation of the English Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Photograph of Lovedale where Mbeki attended high school - The English Anti-Apartheid Movement was a British organisation at the forefront of the international movement opposing South Africa’s apartheid system and supporting South Africa’s non-white population oppressed by apartheid legislation.

- A few months after Mbeki arrived at the University of Sussex, Govan was arrested together with Mandela and Sisulu. After the trial, Govan, Mandela and Sisulu were sentenced to life imprisonment.

- Mbeki travelled to London after finishing his degree at the University of Sussex to work full-time for the ANC’s English headquarters’ propaganda unit. In 1967 he joined the editorial board of the organisation’s official magazine, the African Communist.

- Mbeki also worked at the London office with two prominent figures of the anti-apartheid movement, Oliver Tambo and Yusuf Dadoo, before being sent to the Soviet Union in 1970 for military training.

- Later that year, he arrived in Lusaka and was soon appointed Assistant Secretary of the ANC Revolutionary Council.

- As the Assistant Secretary of the ANC Revolutionary Council, Mbeki played a significant role in turning the international media against apartheid. He was also crucial in establishing the ANC frontline base in Swaziland and other underground organisations.

- Because of these underground organisations, Mbeki and other anti-apartheid activists were detained and deported. They successfully negotiated to be deported to Mozambique, a neutral territory, rather than South Africa.

- Mbeki rose to lead the Department of Communications and Publicity in the 1980s, where he coordinated diplomatic operations to engage more white South Africans in anti-apartheid activities. When delegations of sports, business and cultural representatives visited Lusaka for talks, they all expressed surprise to meet and hear Mbeki’s political stand on apartheid-related issues experienced by Black South Africans.

RISE TO PRESIDENCY

- On 2 February 1990, ANC exiles began to return to South Africa because the announcement came that the organisation was no longer banned. The ANC had to undergo significant internal reorganisation, absorbing the local ANC underground organisations, free activists and other political prisoners from the trade unions. It also had an elderly leadership, which meant that a younger generation of leaders had to be groomed for succession.

- In the year 1993, Mbeki became the ANC National Chairperson.

- Mbeki became one of two national deputy presidents in Mandela’s ANC-led Government of National Unity after the 1994 elections.

- In 1997, Mbeki became the ANC President.

- Pursuant to the 1999 elections, Mbeki was elected President of South Africa because the ANC won by a majority.

PRESIDENCY OF SOUTH AFRICA

- Mbeki’s administration focused on the country’s ongoing transition from apartheid, reducing crime, and combatting the spread of AIDS in Africa.

ECONOMIC POLICY

- As Deputy President, Mbeki was heavily active in economic policy, particularly in pioneering the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) programme, inaugurated in 1996. GEAR was a five-year plan that focused on privatisation and the removal of exchange of controls.

- In contrast to the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) policy that served as the foundation for the ANC’s platform in 1994, GEAR placed a lower priority on growth-oriented and redistributive imperatives. It subscribed to liberalisation, deregulation and privatisation elements.

- Mbeki also emphasised communication between government, business and labour, establishing four working groups – for big business, Black business, trade unions and commercial agriculture. Mbeki regularly met with business and labour leaders to develop confidence and discuss solutions to underlying economic difficulties.

- According to the Free Market Foundation, the average annualised quarter-on-quarter GDP growth was 4.2% under Mbeki’s presidency, with average annual inflation of 5.7%. Mbeki popularised the concept of a dual or two-track economy in South Africa, with severe underdevelopment in one segment of the population, and argued that high growth would only benefit the developed segment, with little benefit to the rest of the population.

- Nonetheless, he expressly pushed for governmental backing to establish a Black capitalist class in South Africa. The government’s Black economic empowerment policy, expanded and consolidated under his administration, was criticised precisely for benefitting only a tiny Black elite and thereby failing to address inequality.

FOREIGN POLICY

- Although Mbeki developed individual strategic ties with foremost African leaders, including the heads of state of Nigeria, Algeria, Mozambique and Tanzania, multilateral collaboration was likely his most important foreign policy tool. Mbeki’s government and Mbeki personally are generally acknowledged as the single most major driving factor behind the establishment of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) in 2001, which attempts to construct a framework for advancing African economic development and cooperation.

- Mbeki served as chairperson of the Non-Aligned Movement from 1999 to 2003 and the Group of 77 + China chairperson in 2006.

- In 2007, following a prolonged diplomatic campaign, South Africa secured a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term.

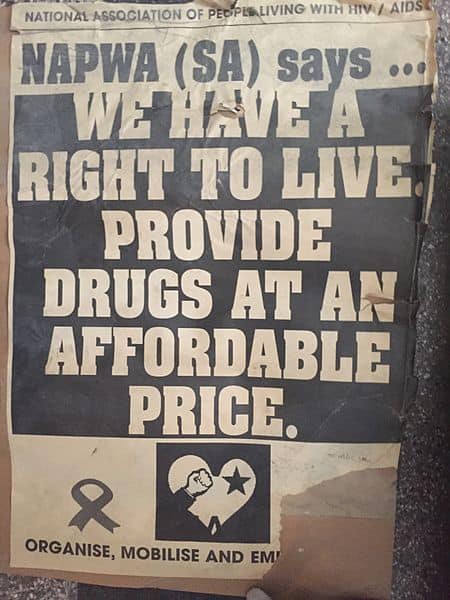

Protest poster asserting that people with AIDS need appropriate drugs to live

HIV/AIDS DENIALISM

- Mbeki was also chastised during his presidency for his HIV/AIDS public statement. He was perceived as sympathetic to or influenced by the ideas of a small minority of experts who questioned the scientific consensus that HIV caused AIDS and that antiretroviral medications were the most effective treatment.

- Mbeki wrote a letter to United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan to emphasise the differences in how the AIDS epidemic manifested in Africa and the West. He also stated that his government was committed to finding the appropriate approach to address the health concern in South Africa.

“Not long ago, people in our own country were slain, tortured, imprisoned, and barred from being mentioned in private or public because the established authority considered their opinions dangerous and discredited. We are now being asked to do exactly what the racist apartheid tyranny we opposed did because it is claimed that there is a scientific position accepted by the majority, against which dissent is forbidden. People who would otherwise fight hard to safeguard the crucially important rights to free thought and expression are now on the front lines of the HIV/AIDS campaign of intellectual intimidation and terrorism...”

- The letter was released to The Washington Post, causing an uproar. During the same period, Mbeki organised a commission to explore the cause of AIDS. The commission was comprised of parasite researchers and orthodox researchers. Commentators assume that his stance was inspired by distrust of the West and a reaction to racist perceptions of the continent and its people.

- During the eight years that Mbeki was president, he continued to express sympathy for HIV/AIDS denial and implemented policies that denied antiretroviral medications to AIDS patients.

- The Mbeki government even withheld assistance from clinics that began using AZT to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child. He also prohibited using nevirapine, a medication that helps prevent HIV infection in babies, supplied by a pharmaceutical company.

- Instead of providing these ‘poisons’, he appointed Manto Tshabalala-Msimang as the country’s health minister shortly after being elected president. She advocated the use of unproven herbal remedies such as ubhejane, garlic, beetroot and lemon juice to treat AIDS, earning her the moniker Dr Beetroot.

- On 7 February 2008, research by Nicoli Nattrass estimated that the failure of Mbeki’s administration to provide ARV drugs until 2006 was responsible for more than 300,000 deaths. Later that year, a study by Pride Chigwedere et al., published in the December 2008 issue of the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, estimated that Mbeki’s HIV/AIDS policies were responsible for more than 330,000 deaths.