Williams v. Mississippi 1898 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Williams v. Mississippi 1898 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background: Henry Williams

- Trial, Appeals and Decisions

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Williams v. Mississippi 1898!

Williams v. Mississippi 1898 was a United States (US) Supreme Court case that examined portions of the state constitution that established voter registration requirements. The US Supreme Court determined that the state’s requirements for voters to pass a literacy test and pay poll taxes were not discriminatory because they applied to all voters. Henry Williams, the plaintiff, stated that Mississippi’s voting rules were upheld to disenfranchise African-Americans, therefore violating the Fourteenth Amendment, which was proposed in response to concerns regarding enslaved people and which addressed citizenship rights and equal protection under the law.

Background: Henry Williams

- In Mississippi, Henry Williams, an African-American man, was prosecuted for the murder of a white man, convicted by an all-white jury, and condemned to death. He claimed that he was denied the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment since the state’s laws prohibited people of his race from serving on juries.

- To be eligible for jury service in Mississippi, a person had to be a registered voter. To be a voter, one had to pay a poll tax and demonstrate to registration officials that they could not only pass a literacy test but also understand or reasonably interpret any clause of the state constitution. Registration officials had sole discretion in determining whether an applicant possessed the required understanding. An African-American Harvard Law School graduate could not satisfy white leaders in Mississippi at the time.

- Disenfranchisement measures in the Mississippi Constitution of 1890 included a poll tax, literacy requirements, and voter registration for jury members. The poll tax and literacy provisions disproportionately disadvantaged African-Americans because they were less wealthy and less educated than whites due to a lack of resources.

- Under Article 12 of the Mississippi State Constitution (1890):

- Sec. 243. A uniform poll tax of two dollars, to be used in aid of the common schools and for no other purpose, is at this moment imposed on every male inhabitant of this state between the ages of twenty-one and sixty years, except persons who are hard of hearing or blind, or who are maimed by loss of hand or foot; said tax to be a lien only upon the taxable property. To aid the common schools in that county, the board of supervisors of any county may increase the poll tax in said county, but in no case shall the entire poll tax exceed in any one year three dollars on each poll. No criminal proceedings shall be allowed to enforce poll tax collection.

- Sec. 244. On and after the first day of January, 1892, every elector shall, in addition to the preceding qualifications, be able to read any section of the constitution of this state; or he shall be able to understand the same when read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation thereof. A new registration shall be made before the next election after January 1892.

- These laws and other more complex restrictions effectively decreased African-American voter eligibility in Mississippi from about 90% in 1890 to slightly under 5% in 1892. African-Americans disappeared from jury lists after 1892.

Trial, Appeals and Decisions

- The Mississippi Supreme Court heard an appeal on the case of Henry Williams. Williams claimed that the jury that condemned him was formed under discriminatory statutes, but the Mississippi Supreme Court affirmed that the rules were not biased in and of themselves. Williams filed an appeal with the US Supreme Court. The case was heard by the US Supreme Court in 1898, with the contention that the voting laws in the 1890 Mississippi Constitution violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

- The US Supreme Court stated that the constitutional provisions were not discriminatory, but Williams maintained that they were when administered by administrative authorities. Administrative personnel were given extensive power in determining which individuals were eligible to vote and serve as jurors. According to Williams, the state used this tactic to deny African-Americans the right to vote.

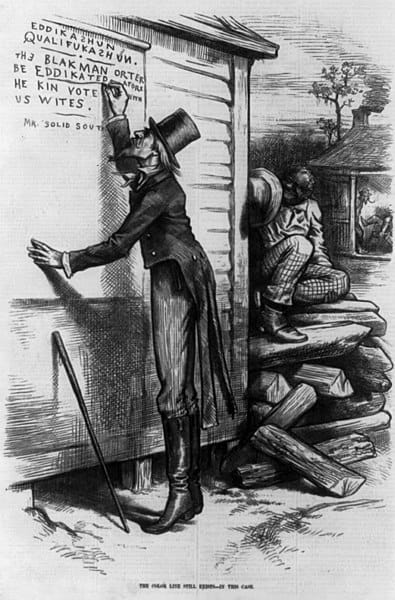

A caricature depicting the suffrage rights of African-Americans. - The trial judge rejected Williams’s reasoning and denied his motion to quash the indictment and transfer the matter from state to federal court. The trial court ruled that removal could not occur because, when racial discrimination was alleged, removal was only justifiable when the bias originated from the state constitution or statutes, not their administration. The trial court sentenced Williams to death by hanging after refusing his motions. The Mississippi Supreme Court heard the appeal but upheld the lower court’s decision.

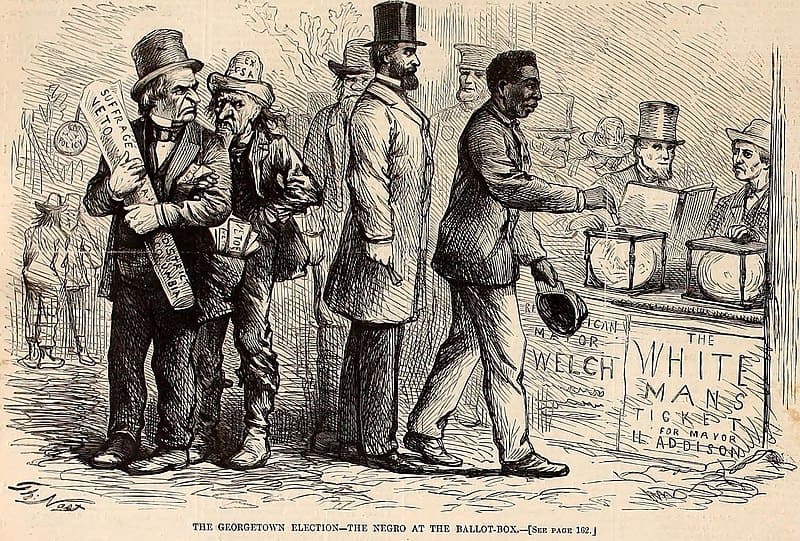

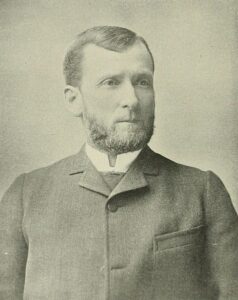

- Justice Joseph McKenna, one of the jurors during the hearing, wrote the court’s opinion, which ruled that the sections of the Mississippi Constitution and legislation at issue were not unconstitutional and upheld the judgement against Williams. McKenna also led that the authority granted to state and local officials in charge of elections and jury selection, while allowing for unconstitutional racial discrimination, was not unconstitutionally disproportionate.

- The court refused to interfere with Mississippi’s application of its laws because:“Mississippi’s constitution and statutes do not appear to discriminate between races, and it has not been demonstrated that their actual administration was wicked; only that evil was possible under them.” - Justice Joseph McKenna

- This was true even after the state admitted that it had administered these regulations with a discriminatory motive.

- The court had previously ruled that governments may not use race as an express basis for discrimination in civil and political spheres. Still, in this case, the justices reasoned that the Fourteenth Amendment was met as long as racial oppression was achieved in a neutral manner.

Justice Joseph McKenna - The court determined that merely demonstrating that parts of the Mississippi Constitution and legislation could be used to discriminate against African-Americans was insufficient: Williams had to show evidence of actual discrimination. The provisions were deemed to conform with the Fourteenth Amendment because they were in general nondiscriminatory and could be applied to all individuals, regardless of race.

- The court determined that administrative personnel, not the law, were discriminating against African-Americans and that there was no judicial recourse for that form of discrimination.

Aftermath

- Through 1908, other Southern states enacted new constitutions with provisions similar to Mississippi’s constitution. With this, thousands of African-Americans and poor Whites were effectively disenfranchised.

- Although some northern Congressmen recommended decreasing the allocation of members in the House of Representatives to southern states to reflect the percentage of disenfranchised African-Americans, no action was taken. With one-party control, white Southern Democrats possessed a considerable voting bloc that they used for decades to reject any Federal legislation prohibiting lynching or public killing.

Image Sources

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_color_line_still_exists%E2%80%94in_this_case_cph.3b29638.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Harper%27s_weekly_(1867)_(14596177519)_The_Georgetown_elections,_the_Negro_at_the_ballot-box_(cropped).jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_McKenna_%28assoc_justice%29.jpg