Key Facts & Summary

- In ancient Egypt, magic, herbs, and spells intertwine and were thought to have curative powers.

- The Ebers Papyrus is the oldest medical text in existence and contains hundreds of remedies to the patients’ illnesses.

- The Egyptians believed that physical sickness was intertwined with the spiritual realm: if one was not feeling well, it meant that they had spiritual blockages or that evil spirits were possessing the sick person.

Overview

Ancient Egyptian civilisations believed that physical wellness was connected to spiritual health. Each time the body manifested discomfort or diseases, doctors were convinced that spirits were clogging and blocking the body’s channels. In order to solve their problems, doctors (or healers) advised both prayers and natural remedies to their patients. Therefore, it is no surprise to discover that medical professions were carried out by priests.

The Ancient Egyptian’s belief in gods, demons, and spirits, blurred the lines between magic and medical scientific detachment. In fact, people believed that illnesses appeared due to the gods’ or the evil spirits’ anger: speaking their enemies language of magic and charms could alleviate their patients from pain. For instance, if one was bitten by a Scorpion, the solution consisted in offering prayers to Serket; whereas a pregnant woman would have prayed to Bes, ‘goddess of magic and medicine’ (Murrell 2018). In essence, Ancient Egyptian civilisations believed that they were inflicted with diseases and pain because they had to learn a life lesson or because they had to redeem their sins.

Before initiating treatment the doctors recited an incantation and prayed the gods to assist the patient’s healing. The doctors/priests also employed talismans in their rituals, and if patients were cured it was thanks to the placebo effect that such procedures played on the psyche and body.

Overall, it can be claimed that ancient Egyptian medicine is grounded in mysticism and herbology.

Since the ancient Egyptians had their own alphabetical and numerical system, they started recording their medical findings, and they compiled the Ebers Papyrus, which today is the most ancient text concerning medical practice. The book was written around 1500 BCE, yet, it contains over seven-hundred remedies, charms and incantations that may date back to 3400 BCE.

The work offers solutions to various conditions concerning dentistry, mental illnesses, the heart, gynaecological issues, pregnancy, dermatology, eyesight, and surgery.

Medical texts were written on papyrus (the Ebers Papyrus is around twenty metres long), and were kept in the temple Per-Ankh (i.e. ‘House of Life’) (Mark 2017). Apart from the Ebers Papyrus, other important medical texts were The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (written in 1800 BCE), which encloses information on pregnancy and contraception methods; The London Medical Papyrus (written between 1782-1570 BCE), deals with issues regarding ‘eyes, skin, burns, and pregnancy’; The Edwin Smith Papyrus, which in the year 1600 BCE was concerned with surgery; The Berlin Medical Papyrus, which treated topics concerning contraception, fertility, and methods to know whether one is pregnant or not; The Hearst Medical Papyrus offered information on urinary and digestive issues; The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus (written around 1200 BCE) dealt with rectal issues and prescribed cannabis to patients suffering from cancer (Mark 2017).

Medical Practices

In ancient Egypt there existed three types of medical practitioners: priests, magicians (who executed a number of spells and charms in order to get rid of evil spirits), and healers called swnw who employed medications when curing their patients (Barr 2014).

Although the ancient Egyptian civilisation’s knowledge in regards to anatomy was not highly developed, they nonetheless had reached certain important understandings and discoveries: in fact, they knew that that the heart pumped blood through the veins and arteries, therefore providing blood to the body. They were also aware that the liver could be infected and could suffer diseases, however, they did not know what caused them.

On the other hand, doctors believed that a women’s uterus floated within the body. Moreover, if a woman was witnessing vaginal discharge, doctors prescribed the following: ‘You should treat it with a measure of carob fruit, a measure of pellets, 1 hin of cow milk. Boil, cool, mix together, drink on 4 mornings. (Mark 2017; citing Column I.8-12). Whereas if the pain was experienced in the lower abdomen, then ‘fumigation of the womb’ (i.e. purifying with incense or other fumes) was advised (Mark 2017).

But how could a doctor predict a woman’s pregnancy? The method seems quite absurd today: however, an onion was placed the vaginal canal and if the next morning the woman’s breath presented an onion smell, then it meant she was expecting a child. Yet, this was not the only method: in fact, in some instances emmer and barely were ‘doused with a woman’s urine; and if the plants flourished’ it signified pregnancy: if emmer was the first of the two plants to sprout, then the child would be female; if barely sprouted first, the child would be male (Mark 2017).

In order to cure simple headaches, or more complicated issues such as epilepsy, abscesses and blood clots, ancient Egyptian civilisations employed harsh measures such as trepanation, which consists in drilling a hole in the skull in order to relieve pressure and perform simple operations. Such a technique was also used as a method to exorcise patients from evil spirits and in an attempt to relieve mental illnesses.

In other instances, if patients were suffering from headaches, medical practitioners would advise to take ‘an elixir containing human flesh, blood or bone’, or ‘mummy powder’, which supposedly had ‘magical properties’ (Andrews 2014). In fact, by ingesting the remains of a corpse, the patient believed she was also ingesting part of their spirit and their qualities, thus obtaining a higher rate of ‘vitality and wellbeing’ (Andrews 2014). Such macabre practices belong to a branch of medicine called ‘corpse medicine’ which was used for hundreds of years, up to the XVII century (in fact, the king of England Charles II, drank ‘a restorative brew made from crumbled human skull and alcohol’) (Andres 2014). In this view, eating human fat would relieve the patients from muscle aches and ingesting skull would relieve migraines and headaches.

On the other hand, for ancient Egyptian civilisations, the heart was the ‘centre of the body, spirit, and soul’ (Barr 2017).

Wounds

During the ancient Egyptian times’ wounds were taken care of by applying a concoction of ‘honey, willow leaves, acacia seeds, and other herbs’, whereas bleeding was stopped with ‘raw meat, sawdust, animal fat, or dung’ (Health and Fitness History).

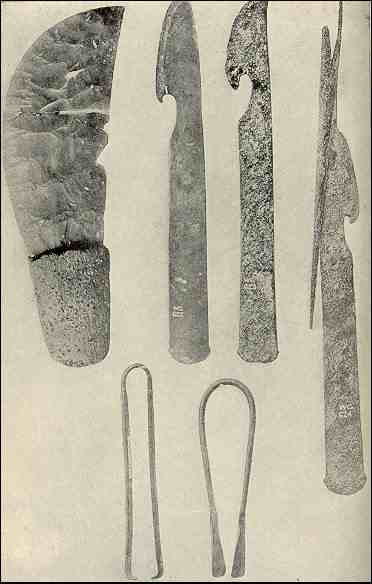

Surgical procedures were carried out with ‘forceps, bone saws, [and] scalpels’ (Health and Fitness History 2017).

Ingredients in Egyptian Medicine

Doctors prescribed specific foods since they exhibited curative properties for certain diseases. For instance, some of the most popular ingredients employed by the healers were: aloe, acacia seeds and leaves, cannabis, castor oil, cedar oil, cilantro, dates, fish, frankincense, garlic, goose fat, honey, juniper, Mandrake, pomegranate juice and root, thyme, and willow leaves (Health and Fitness History 2017).

However, also more macabre ingredients were often prescribed: for instance ‘ Lizard blood, dead mice, mud and mouldy bread were all used as topical ointments and dressings, and women were sometimes dosed with horse saliva as a cure for an impaired libido’ (Andrews 2014).

Medicines were often ‘mixed with beer, wine, or honey’ which were thought to provide the patients with medical benefits. In fact, beer was considered as the gods’ gift to humanity since it contributed to one’s ‘health and enjoyment’ (Mark 2017). The protectors of beer were the female divinities Tenenet and Hathor, and the male god Set. Although Set is considered the God of chaos, violence, upheavals, storms, and had murdered his own brother Osiris, he was nonetheless a powerful god. In fact, the pharaoh of Egypt Seti I, had particularly honoured the God, and an incantation was created in order to cure unknown illnesses through the use of beer. The spell is recited in the following way: ‘There is no restraining Set. Let him carry out his desire to capture a heart in that name ‘beer’ of his – To confuse a heart, and to capture the heart of an enemy’ (Mark 2017; citing Roberts, 98).

Although today it is well known that Mercury is a poisonous substance, during the ancient Egyptian period it was considered a potent liquid that could increase one’s lifespan: in fact, it was claimed that by ingesting Mercury one would ‘gain eternal life and the ability to walk on water’ (Andrews 2014). Such a practice was adopted by the Chinese Emperor Quin She Huang, who subsequently died due to poisoning.

The Demotic Magical Papyrus is entirely dedicated to spell, charms, and rituals: all the material contained in such book borders the mystical and the occult. Some of the papyrus’ incantations attempted to bring the dead back to life.

Medicine and Healing through Deities

Nefertem was the god of aromatherapy and perfumes. His name derives from ancient Egyptian ‘nfr-tm’ which signifies ‘perfect, without any equals’. According to tradition, Nefertem had donated to Ra (God of immortality) a lotus flower, which symbolised birth and regeneration.

Bes, Tueret, Hetet, Imhotep and Neith were the protectors of pregnant women and childbirth.

Bibliography

[1.] Andrews, E. (2014). 7 Unusual Ancient Medical Techniques. Available from: https://www.history.com/news/7-unusual-ancient-medical-techniques

[2.] Barr, J. (2014). Vascular Medicine and Surgery in Ancient Egypt. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 60 (1). Pp. 260-263.

[3.] Health and Fitness History (2017). Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Available from: https://healthandfitnesshistory.com/ancient-medicine/ancient-egyptian-medicine/

[4.] Mark, J.J. (2017). Egyptian Medical Treatments. Ancient History Encyclopaedia. Available from: https://www.ancient.eu/article/51/egyptian-medical-treatments/

[5.] Murrell, D. (2018). What was Ancient Egyptian medicine like? Medical News Today. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323633.php

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b7/Egyptian_Doctor_healing_laborers_on_papyrus.jpg

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9d/Ancient_Egypt_Medical_tools2.jpg