Download Lincoln Steffens Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Lincoln Steffens to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Early life and career

- Muckraking journalism

- Investigative publication and other works

- Campaigns for McNamara brothers and the Russian Revolution

- Autobiography and later life

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Lincoln Steffens!

- Lincoln Steffens was an American investigative journalist and one of the well-known muckrakers of the Progressive Era. He specialised in investigating corruption in the government, which he detailed in a collection of articles published in his famous work, The Shames of the Cities.

- When muckraking journalism became less popular, he began to believe in the power of revolution to change societies thus he was involved in reporting on the Mexican Revolution and later the Russian Revolution. His enthusiasm for communism dwindled when he started working on his autobiography which became a bestseller.

Early life and career

- Born in San Francisco, California, Steffens was the only son and the eldest of the four children of Elizabeth Louisa Steffens and Joseph Steffens.

- He spent most of his childhood in their family mansion, a Victorian house bought in 1887 in Sacramento, the state capital.

- Born to an affluent businessman, he attended a military academy where his rebelliousness that was to lead him to political radicalism was first observed.

- After graduating, he went to the University of California at Berkeley, where he was convinced to undertake a study of philosophy since his interests in life and politics were emerging.

- Upon graduating in 1889, he studied psychology at universities together with Wilhelm Wundt in Germany and Jean-Martin Charcot in France.

- He travelled from Berlin to Heidelberg, Leipzig, Paris and London before moving to New York City.

- He was already secretly married to an American girl he had met in Germany when he returned to New York.

- In 1892, Steffens officially became a reporter for the New York Evening Post where he worked for nine years.

- He had access to abundant evidence of corruption of politicians by businessmen in pursuit of special privileges.

- This gave him the means and the confidence to fight against corruption.

- He became a managing editor of McClure’s Magazine where he continued publishing influential articles.

Muckraking journalism

- At a time when many politicians were corrupt and were practising nepotism, the journalists during the Progressive Era exposed many political issues surrounding the government and society.

- Fascinated by the web of corruption in the government, Steffens was already an active and known muckraking journalist.

- He was recruited as an editor of McClure’s Magazine on the recommendation of Norman Hapgood, the editor of Collier’s Weekly.

- He was part of the celebrated muckraking trio together with Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker.

- Other writers who worked for this magazine in that period include: Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Willa Cather and Burton J. Hendrick.

- Whilst working for McClure’s, Steffens wrote about governmental and political corruption.

- He published “Tweed Days in St. Louis”, in which he described the disparity between reality and the image portrayed by those in power.

- This was caused by the corruption in municipal government, which was also the case in most cities, towns and villages in America.

- During this period, Steffens was popular as his articles became widely read.

- Ida Tarbell was hired as a staff writer, who went on and wrote a 20-part series on Abraham Lincoln.

- Muckraking, a term coined by President Theodore Roosevelt, doubled the magazine’s circulation.

- Roosevelt condemned the writers for their seemingly singular focus on covering the negative aspects of society thus he called them muckrakers.

- Steffens became even more motivated in using McClure’s Magazine to campaign against corruption in politics and businesses.

Investigative publication and other works

- Steffens continued to specialise in investigating the government, and published works with the aim of seeking political reforms in urban America.

- He compiled the series of articles he wrote in McClure’s and published them into a book entitled “The Shame of the Cities” in 1904.

- This book, which became a bestseller, included Tweed Days in St. Louis, The Shame of Minneapolis, The Shamelessness of St. Louis, Pittsburg: A City Ashamed, Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented, Chicago: Half free and Fighting On, and New York: Good Government to the Test.

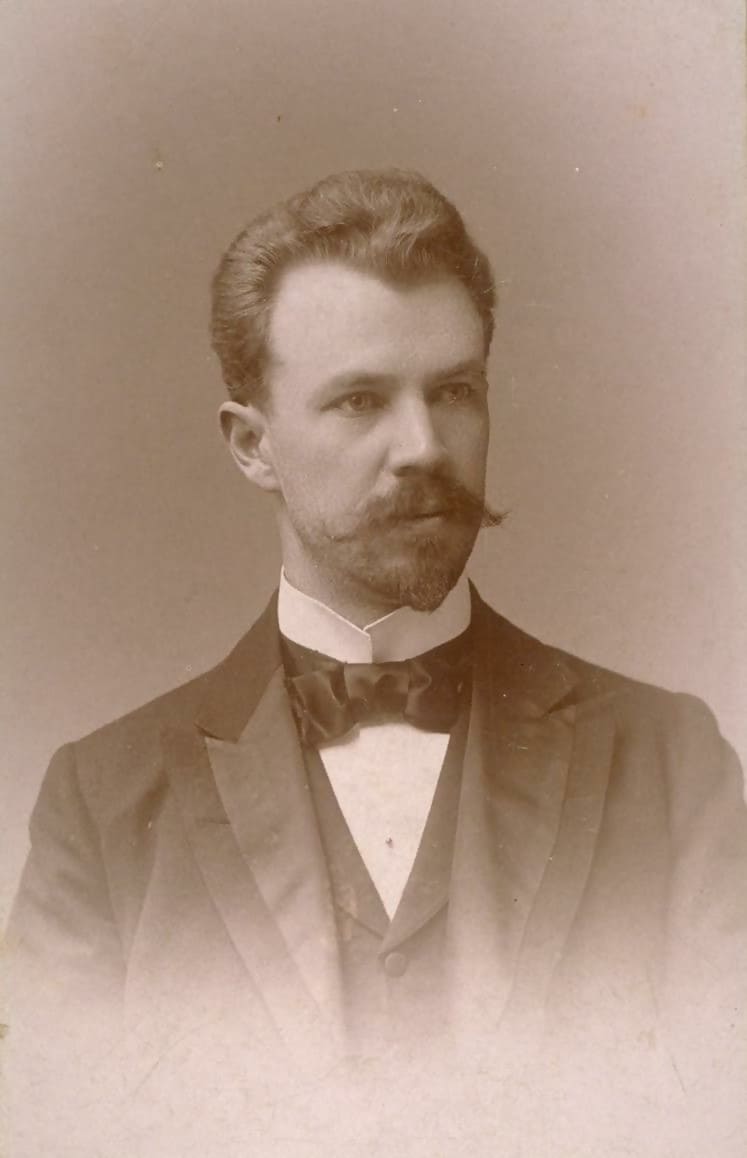

- Whilst he was known for calling out the politicians on their questionable works, he praised politicians whom he considered to be worthy such as Robert La Follette and Seth Low.

- Through Steffens’ investigations detailed in the “The Shame of the Cities”, the government took action to stop the corruption by passing new laws and legislations, albeit rather slowly.

- He also wrote “The Traitor State” in 1905, in which he criticised New Jersey for patronising incorporation.

- This work was followed by an investigation into state politicians thus he published “The Struggle for Self-Government” in 1906.

- He left McClure’s along with Tarbell and Baker and joined The American Magazine.

- Steffens gained recognition due to his nationwide lecture tours, where he raised questions and tried to provoke outrage to bring about political reforms.

Campaigns for McNamara brothers and the Russian Revolution

- Steffens continued to write about corruption until 1910 when muckraking journalism became less popular.

- He began to doubt the effectiveness of reform politics. He joined John Reed to report on Pancho Villa and his army.

- He strongly supported the rebels and formed the view that revolution was the way to change capitalism in Mexico.

- When the Los Angeles Times was bombed by the McNamara brothers in 1910, Steffens went to Los Angeles and talked to the perpetrators.

- The bombing killed 21 newspaper employees and injured 100 more.

- Steffens offered to defend the actions of the McNamara brothers in print but his intervention proved to be a disaster.

- His interest in the trial and to help the McNamara brothers were based on his Christian belief and his intention to improve labour relations.

- He also believed in the idea of the Golden Rule – a faith in the fundamental goodness of people – which was much attacked by the radicals.

- By this time, finding magazines that would publish his work was difficult and Steffens slowly lost his American audience.

- In January 1919, Steffens and his friend, William Christian Bullitt, assistant secretary of state, argued that they should be sent to Russia to open up negotiations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

- The Secretary of State Robert Lansing granted them permission on 18 February.

- Steffens and Bullitt had a meeting with Lenin in Petrograd on 14 March and it was agreed that the Red Army would leave Siberia, the Urals, the Caucasus, the Archangel and Murmansk regions, Finland, the Baltic states, and most of the Ukraine as long as an agreement was signed.

- President Woodrow Wilson and David L. George rejected the idea.

- When the terms of the Versailles Peace Conference were published, Bullitt resigned in protest.

- Steffens returned to the United States and made his famous remark about the new Soviet Society,

- When he returned from Russia, he promoted his view of the Soviet Revolution as he was inspired by the success of the Bolshevik Revolution and strongly believed in communism since he associated the economic system of capitalism with the cause of social corruption.

- He continued to support communist activities but refused to identify with a specific party or doctrine.

Autobiography and later life

- Whilst various publications discriminated against Steffens, several publishers had offered him contracts to write his autobiography.

- Steffens married Ella Winter, a socialist writer he met whilst reporting on the Versailles Peace Conference.

- They lived in Italy for two years where their son Peter was born.

- He started to work on his autobiography in Italy and soon their family relocated to Carmel, California.

- Steffens and Winter soon became controversial figures in the leftist politics of the region.

- “The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens” was published in 1931, only two years after the Great Depression.

- It recorded Steffens’ progressing views from being a sophisticated intellectual to reformer to revolutionary which was relatable to many people.

- He gained back his prominence as a writer as his autobiography became a bestseller but an illness halted his lecture tour in America in 1933.

- Steffens supported the American Writer’s Congress whose main objective was to give aid to those fighting Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Europe.

- In 1934, Steffens and his wife helped found the San Francisco Workers' School (later the California Labor School), where he also served as an advisor.

- He died of heart failure at his home in Carmel, California on 9 August 1936.

Image source:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c2/Lincoln_Steffens.jpg

[2.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McClure%27s#/media/File:McCluresCoverJan1901.jpg

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7c/Furuseth-La_Follette-Steffens-1915.jpeg

[4.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_Revolution#/media/File:Soldiers_demonstration.February_1917.jpg