Key Facts & Summary

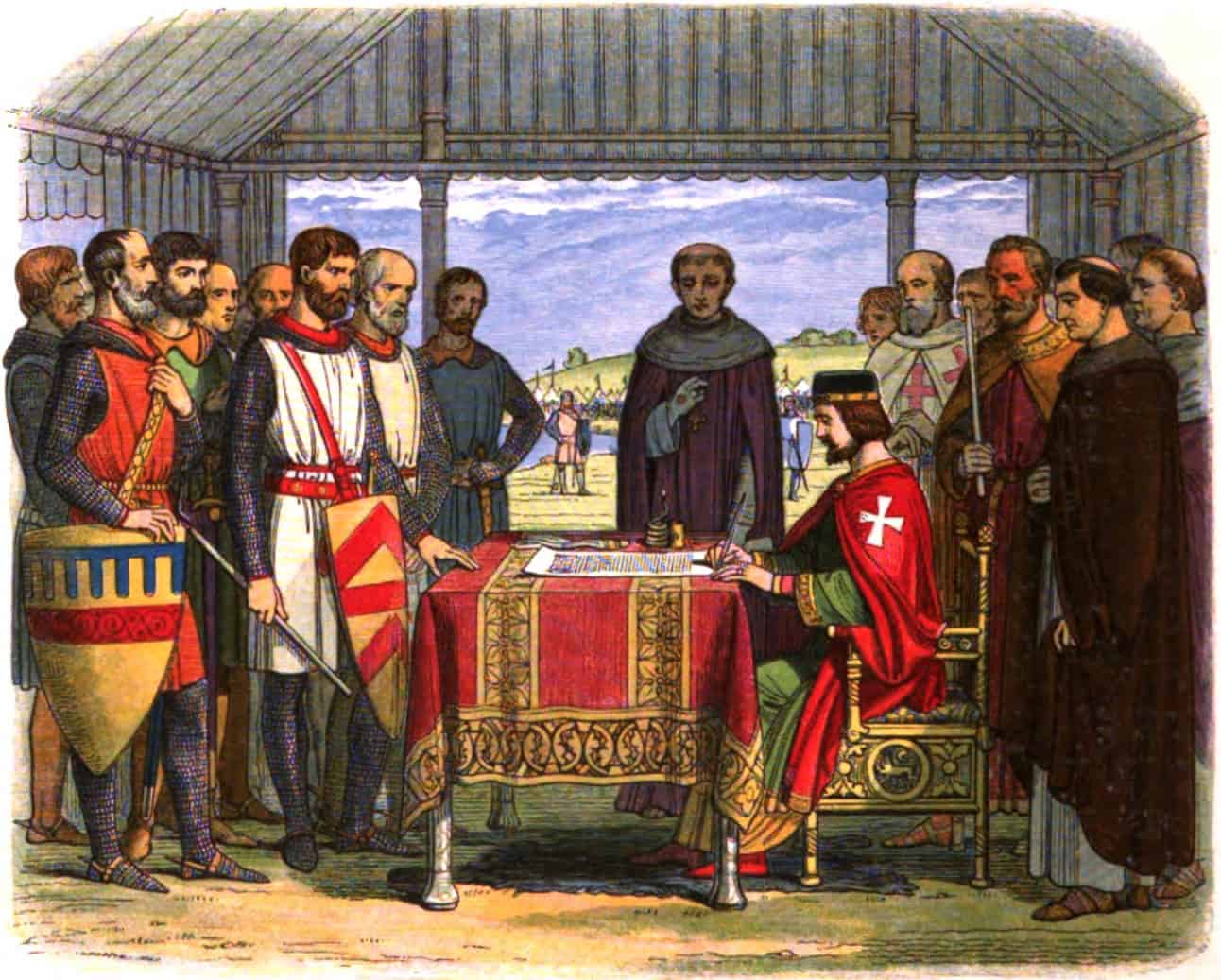

- The Magna Carta was sealed on June 15, 1215, by King John of England (also nicknamed John Without Land).

- It was drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury with the intention of restoring peace between the unpopular king and a group of commoners. He granted the protection of typical Church rights, the protection of civilians and illegal detention. He also guaranteed rapid justice and the limitation of feudal payments to the crown.

- Even though it presented itself as a unilateral concession by the king, it actually constituted a contract for the recognition of reciprocal rights.

- After the death of King John, the government of William the Marshal, regent of his infant successor Henry III, had the document issued again in 1216 and was stripped of some of its most radical contents. Its latest and last revision was in 1297.

- Although the Magna Carta has been modified several times over the centuries by ordinary laws issued by the parliament, it is still considered a valuable and fundamental document.

Overview

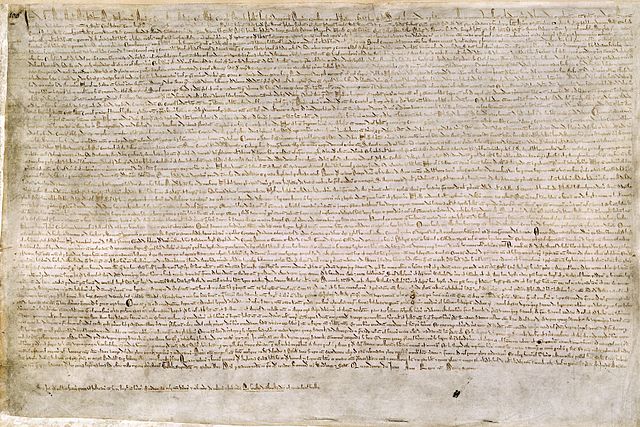

The Magna Carta is a document with which King John of England granted certain privileges and right to his subjects. It was sealed in June 1215. In later ages, it came to be regarded as the cornerstone of English liberty. It consists of a preamble and 63 clauses, written in Latin, presented by the king to a group of rebellious barons, his royal vassals, at Runnymede, a meadow beside the Themes not far from London.

The Magna Carta grants those privileges and liberties that were to become fundamental to the development of a constitutional government in England. The document had no title in 1215. It was only later when it came to be viewed as guaranteeing basic political and legal rights, that it was called Magna Carta, or the Great Charter. Two copies are in the British Museum, one in Lincoln Cathedral, and one in Salisbury Cathedral, in England.

Background

After the Norman Conquest, in 1066, England was ruled by able Norman and Angevin kings who centralised the government, developed new institutions such as the exchequer, and reformed the legal system. By the time of Henry II, who regained from 1154 to 1189, England was the best-governed kingdom of Western Europe. Yet, its official government was beset by the danger of inadequate control over the royal powers. Thus, an arbitrary king like John, who succeeded his brother Richard I in 1199, was able to use his great authority to exploit his subjects.

Most historians agree that John was an intelligent administrator capable of tremendous work, but that he was also capricious, lazy, greedy, untrustworthy, scornful of accepted behaviour, and unskilled in waging war. By 1206 he had lost all his continental possessions except Aquitaine to Philip II of France. This loss, which discredited John in England, encouraged his barons to seek redress of their wrongs.

Among their grievances were that the king had demanded excessive military service or exorbitant payments of money in lieu of it; that he had sold offices, favoured friends, and extorted money from his subjects; that he had increased old taxes without obtaining proper consent from his vassals; and that he had shown little respect for feudal law, breaking it when it suited his ends. The royal courts had become vehicles for his will, cases were too frequently decided by royal whim, and crushing fines and penalties too frequently meted out.

Moreover, so estranged were John’s relations with the Church, and so often had he despoiled it of possessions, that the clergy also feared and distrusted him. Pope Innocent III placed an interdict on England in 1208 and excommunicated John in 1209. John did not seek peace with the Church and did not make amends until 1213. Thus, on the eve of Magna Carta John had alienated most of his kingdom. His despotic exercise of authority led the baron to unite to humble him in 1215.

Provisions of the Charter

Most of the 63 clauses of the Magna Carta were concerned with guaranteeing feudal law and benefited only the feudal nobility. The Church was granted its traditional freedom and privileges. A few clauses dealt with the rights of the middle class in the towns and relieved some economic inequities. But the ordinary freeman and peasant, who made up the vast bulk of England’s population, were scarcely mentioned. The Magna Carta was not, therefore, a great democratic document, securing fundamental liberties for all. Instead, it was essentially a feudal charter assuring privileges to the aristocracy.

Some clauses, however, contained broad provisions that later came to be more flexibility interpreted. One clause stated that the royal vassals must be summoned to councils to give their advice and consent to important affairs of the realm. Another stipulated that the king demanded military service and the royal vassals had the right to decide whether to serve or substitute a money payment, called scutage. Another enjoyed that all extraordinary taxes had to be approved by the royal vassals. In the XIV and XV centuries, when the power of the feudal aristocracy had declined and the non-feudal classes had acquired political power, these clauses were cited as evidence that there should be no legislation or taxation without the consent of the king’s subjects given in parliament, and that the king could not arbitrarily make laws or impose taxes.

Certain clauses pertaining to the law were extremely important for their influence over the future legal proceedings. John had had to agree that henceforth justice could not be bought or sold. By clause 39, which declared that no freeman could be arrested, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled, or ‘in anyway destroyed’ except by the lawful judgment of his person by the law of the land, the king promised that every freeman would receive justice in a court of law before any action was taken against him. This is the seed of the basic principle due process of law that guarantees men against arbitrary imprisonment or punishment and assures them of proper trial. Although trial by jury had been introduced for civil cases during the reign of Henry II, there was no jury trial for criminal cases until later in the XIII century. However, XVII century lawyers and historians interpreted the Magna Carta as having provided for such trials.

To make sure that John abided by his promises, clause 61 established a baronial council to enforce adherence, if necessary by force of arms. This, however, cannot be interpreted as providing for constitutional control over the king, which came only later in the Middle Ages when parliament gained control over legislation and taxation. The importance of the Magna Carta in 1215 was that for the first time the king’s vassals had forced him to agree that he was and should be subject to the law and that for the first time royal power had been checked.

Reissues and Confirmations

Little more than a year after John had granted the Magna Carta he died and was succeeded by his infant son, Henry III. In November 1216, soon after his coronation, the charter was reissued in Henry’s name, with some clauses of the original charter omitted. This reissue of the Magna Carta was concerned chiefly with matters lying within the sphere of private law rather than relating to the administration of government or to the control of the royal power since the barons were confident that they could restrain an infant king. A second reissue of the Magna Carta took place in November 1217, again with revisions. A third and final reissue, in February 1225 shortly after Henry was declared of legal age, was almost identical to the reissue of 1217. This marked the final form assumed by the Magna Carta and was the document known in later Medieval times. It was this version that was considered to be the beginning os statute law and that was confirmed on numerous occasions by the kings of England during the later Middle Ages.

Historical Importance

In three centuries after 1215, the Magna Carta became a symbol for the restriction of arbitrary royal power and came gradually to be viewed as embodying the fundamental law of the land. Not until the XVII century and later, however, was it interpreted as establishing constitutional control of the king, the doctrine of no taxation or legislation without the consent of parliament, trial by jury for criminal cases, and guarantees against arbitrary imprisonment and punishment, and the concepts of democratic government and impartial justice. In their bitter struggle with the Stuart kings in the early XVII century, lawyers and members of parliament like Sir Edward Coke began to construe the Magna Carta as assuring these rights. In the XVIII century, the jurist William Blackstone incorporated this interpretation in his famous Commentaries on the Laws of England. Historians and statesmen of the XIX century praised the Magna Carta as the greatest safeguard of English liberties. Thus construed, the charter influenced the political and legal ideas of men in America and played a vital role in colonial history, in the American Revolution, and in the framing of the Constitution of the United States. Interpreted by successive generations to serve their needs, the Magna Carta has contributed greatly to the development of constitutional government and an impartial juridical system throughout the English speaking countries.

Bibliography

[1.] Breay, C. (2010). Magna Carta: Manuscripts and Myths. London: The British Library.

[2.] Breay, C. and Harrison, J. (2015). Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy. London: The British Library.

[3.] Carpenter, D. A. (2004). Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London: Penguin.

[4.] Powicke, F. M. (1963). The Thirteenth Century 1216–1307. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[5.] Turner, R. (2009). King John: England’s Evil King?. Stroud: History Press.

Image sources:

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/King_John.jpg

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c0/Magna_charta_cum_statutis_angliae_p1.jpg