Download Medieval Food and Drink Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Medieval Food and Drink to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Cereals were consumed in the form of bread, oatmeal, polenta, and pasta by virtually all members of society.

- Vegetables represented an important supplement to the cereal-based diet. Meat was more expensive and, therefore, considered a more prestigious food and was mostly present on the tables of the rich and noble.

- The most common types of meat were pork and chicken, whereas beef was less common.

- Cod and herring were very common in the diet of northern populations.

Key Facts And Information

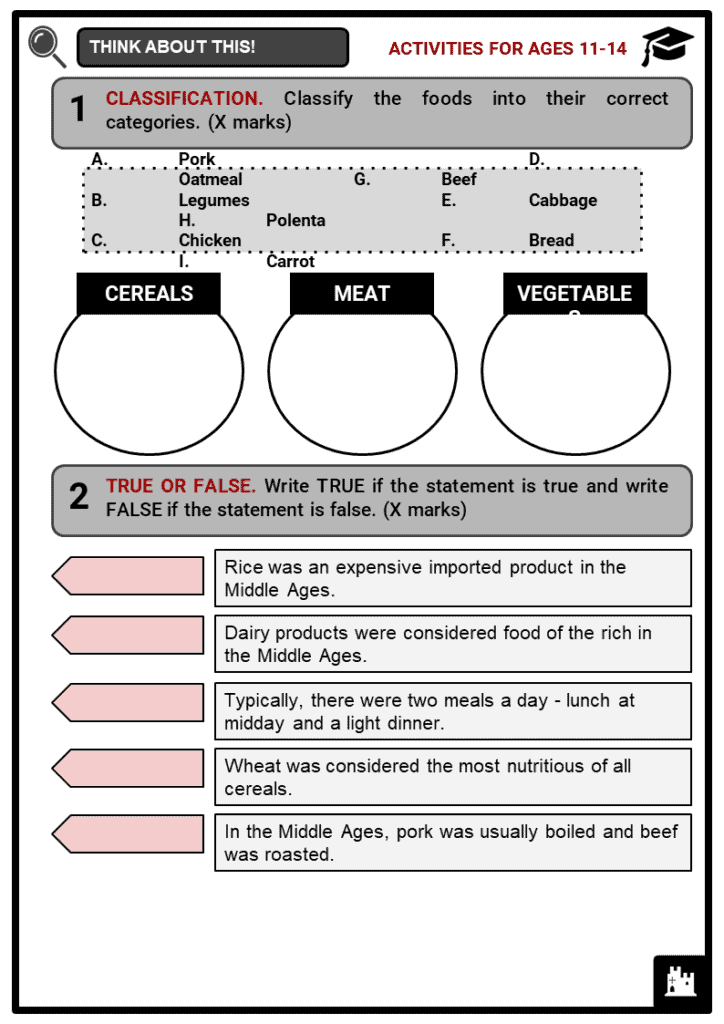

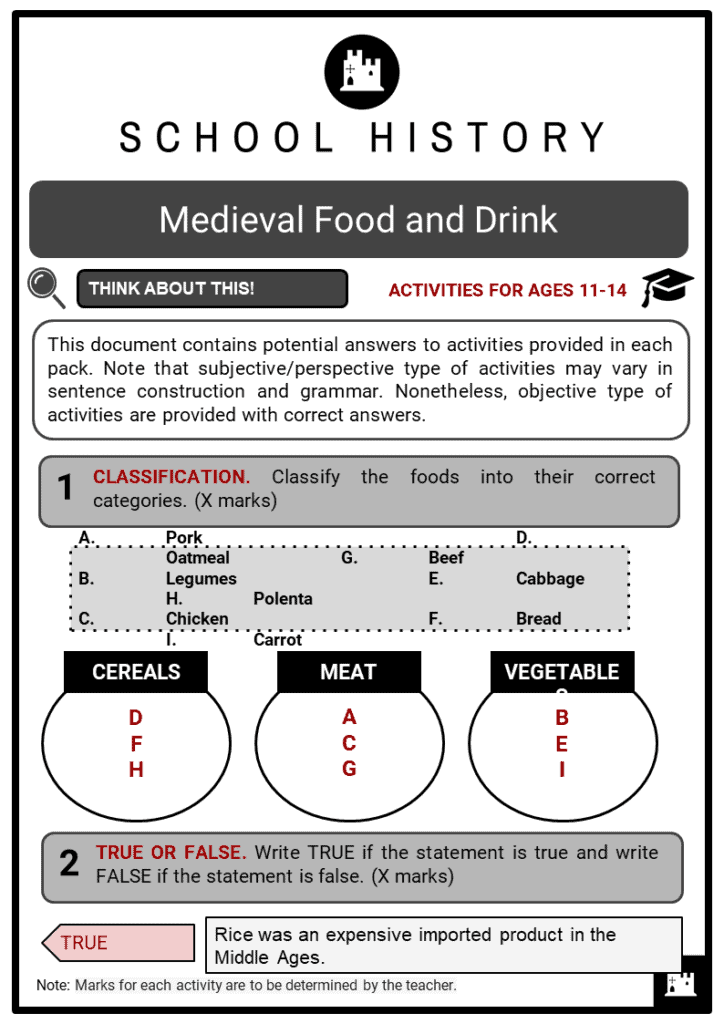

Diet restrictions depending on social class

Before delving into the types of foods that people ate in the Middle Ages, it is necessary to be aware of the social distinctions present at the time. Medieval society was stratified and strictly divided into classes. In an age where famines were quite frequent and social hierarchies were often enforced with violence, food was an important sign of social distinction and possessed great value.

Following the ideology of the era, society was made up of individuals belonging to the nobility, the clergy and the common people (i.e. most of the working class). The relationship between the classes was strictly hierarchical: the nobility and the clergy claimed their material and spiritual superiority over ordinary people. Between the nobility and the clergy, there also existed a multitude of levels that ranged from the king to the Pope, from the dukes to the bishops down to their subordinates such as knights and priests. In general, everyone was expected to remain within the social class to which they were born and to respect the authority of the ruling classes. Political power was shown not only through government action but also by displaying one’s own wealth. The nobles exhibited their refined manners at the table and were able to afford eating fresh meat flavoured with exotic spices. By contrast, men of toil had to be content with crude barley bread and salted pork. They were not expected to know the correct etiquette. The diet of nobles and high-level prelates was considered both a sign of their refined physical constitution and their economic prosperity. The digestive system of a gentleman was believed to be more delicate than that of one of his peasants and subordinates and, therefore, required more refined foods.

Food

Before the 14th century, bread was not a very common food among the lower classes, especially in the north where wheat grew with difficulty. Bread-based diets gradually became more common during the 15th century.

Throughout the Middle Ages, rice remained an expensive imported product and began to be cultivated in northern Italy only towards the end of the era. Wheat was common throughout Europe and considered the most nutritious of all cereals and, as a consequence, it was regarded as the most prestigious and most expensive cereal.

Although cereals represented the basis of every meal, vegetables such as cabbage, beets, onions, garlic, and carrots were also very common foods. Many of these vegetables were consumed on a daily basis by farmers and manual workers and, therefore, were considered less prestigious foods than meat.

Legumes such as chickpeas, beans, and peas were also commonly consumed and were an essential source of protein, especially for the lower classes.

Except for peas, legumes were often viewed with suspicion by the dieticians of the time, who recommended the upper classes avoid them because they caused flatulence and because they were associated with peasants.

Meals

Typically, there were two meals a day: lunch at midday and a light dinner in the evening. The two-meal system remained widespread until the late Middle Ages. Small snacks between meals were quite common, but it was also a matter of social class, as those who did not have to do arduous manual work did without them.

For practical reasons, morning breakfast was consumed by the working classes and was tolerated for children, women, the elderly and the sick. However, since the church preached against the sins of gluttony and other weaknesses of the flesh, people tended to be ashamed of having breakfast in the morning, since it was considered a sign of weakness.

Evening banquets and dinners consumed late at night with considerable consumption of alcoholic beverages were considered immoral. Alcohol, in particular, was associated with gambling, vulgar language, drunkenness, and lewd behaviour. Although the Church disapproved, small meals and snacks were common and those who worked generally had permission from their employers to buy food to nibble on during their breaks.

Preparation of food

Cooking included the use of fire: since stoves were not invented until the 18th century, people cooked directly over the fire. Ovens were also used, however, building them was very expensive and they were only found in larger houses and baker’s shops. Often, medieval communities had an oven whose ownership was shared. Therefore, essential food was prepared in public rather than private. There also existed portable ovens that moved thanks to wheels: they were used to sell cakes and pies along the streets of medieval cities.

Most people cooked in simple pots, and soups and stews were, therefore, the most common dishes.

In some dishes, fruits were mixed with meat, eggs, and fish. For example, the tart de brymlent is a recipe that dates back to the 14th century. This dish was a salmon or cod pie that included a mixture of figs, prunes, raisins, apples, and pears.

Following the four humours medical and dietary prescriptions of the time, food had to be combined with sauces, spices, and other specific ingredients depending on the nature of food. For instance, fish was considered cold and humid in nature, therefore, it was believed that the best way to cook it was by frying it, by placing it in the oven, or by seasoning it with hot and dry spices. Beef was considered dry and warm and, as a consequence, it was boiled. Pork was regarded as warm and moist, therefore, it had to be roasted.

Food preservation

The methods of food preservation were essentially the same as those that had been used since ancient times and things did not change much until the beginning of the 19th century with the introduction of food preservation in airtight metal cans.

One of the simplest and most common methods to preserve food consisted of heating the food, or exposing it to the wind in order to eliminate its humidity and prolong the life of almost all types of food.

In fact, drying food drastically reduces the activity of various hydrophilic microorganisms that cause decomposition. While in hot climates this result was reached mostly by exposing the food to the sun, in the colder countries wind or ovens were exploited. Moreover, subjecting foods to certain chemical processes, such as smoking, salting, fermentation or preservation in the form of jam, served to make the food last longer. These methods were advantageous because they contributed to the creation of new flavours. Smoking or salting meat in the fall was a fairly widespread strategy to avoid having to feed more animals than necessary during the harsh winter months. It was common to add a lot of butter (around 5-10%) because it did not deteriorate. Vegetables, eggs, and fish were often pickled. Another method of food preservation consisted of creating a thick crust around the food, cooking it in sugar, honey or fat, and then storing it. The changes caused by the bacteria were also exploited in various ways: cereals, fruit and grapes were transformed into alcoholic beverages, whilst milk was fermented and transformed into a wide variety of cheeses and dairy products.

Beverages

In modern times, water is a popular choice for a drink to accompany a meal. In the Middle Ages, however, concerns about its purity, medical recommendations and its low prestige made it a secondary choice and alcoholic beverages were always preferred. In fact, they were considered more nutritious and better for promoting digestion than water. Wine was consumed daily in most of France and in all the countries of the Mediterranean basin where vines were cultivated. In the northern countries, it was the drink preferred by the bourgeoisie and only the upper classes that could afford it. However, it was much less common among the peasants and the working class. In the Nordic countries, ordinary people’s most popular drink was beer. However, since it was difficult to preserve beer for a long time, it was mostly consumed fresh and it was consequently less clear than modern beers and had a lower percentage of alcohol.

Milk was not drunk by adults. It was reserved for the poor, the sick, children, and the elderly. Milk was much less widespread than other dairy products due to the lack of technologies to prevent it from going sour quickly.

Juices were prepared with different fruits and berries: pomegranate and blackberry wine, as well as pear and apple cider, were especially popular in the Nordic countries where these fruits grew abundantly.

Among the surviving medieval drinks that we still drink in the present day is prunellé, which is made with wild plums and is currently called slivovitz. Another example is mead, a type of wine made from honey.

Bibliography

[1.] Adamson, M. W. (editor), Food in the Middle Ages: A Book of Essays. Garland, New York. 1995.

[2.] Dyer, C., Everyday life in medieval England, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000

[3.] Freedman, P., Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. Yale University Press, New Haven. 2008.

[4.] Harvey, B.F., Living and dying in England, 1100–1540: the monastic experience, Oxford University Press, 1993

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Peasants_breaking_bread.jpg

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/Medieval_peasant_meal.jpg

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c0/Cuisine_m%C3%A9di%C3%A9vale.jpg

[4.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d3/Monk_sneaking_a_drink.jpg