Hadrian's Wall Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Hadrian's Wall to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Origin and Construction

- Purpose of the Wall

- Life Inside the Wall

- Wall after Hadrian’s Death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Hadrian’s Wall!

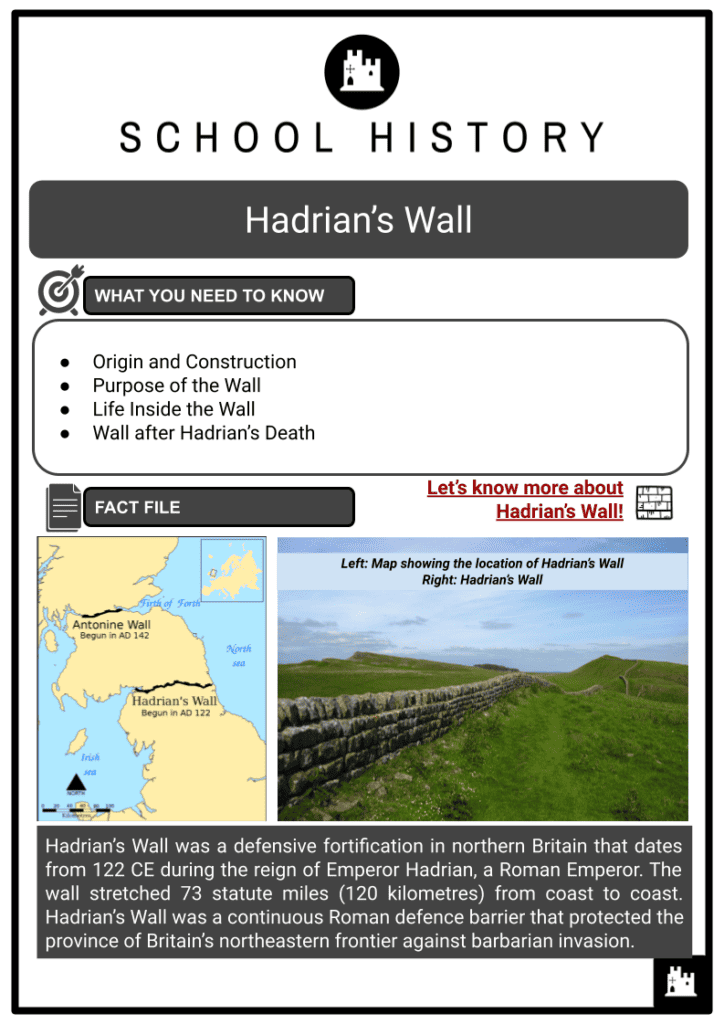

Hadrian’s Wall was a defensive fortification in northern Britain that dates from 122 CE during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, a Roman Emperor. The wall stretched 73 statute miles (120 kilometres) from coast to coast. Hadrian’s Wall was a continuous Roman defence barrier that protected the province of Britain’s northeastern frontier against barbarian invasion.

ORIGIN AND CONSTRUCTION

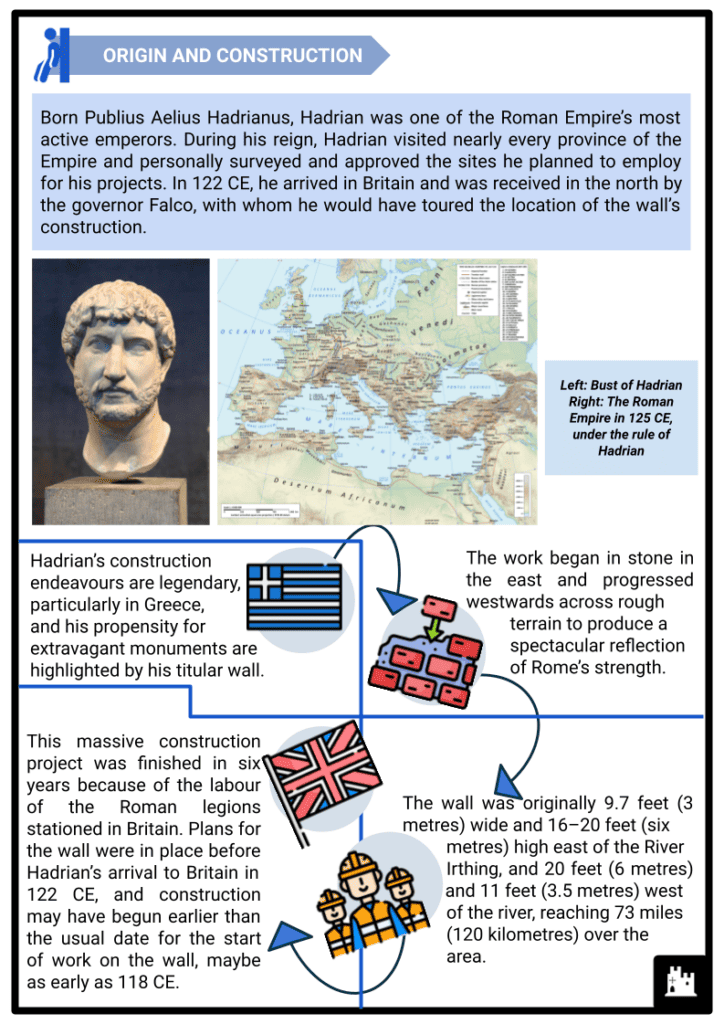

- Born Publius Aelius Hadrianus, Hadrian was one of the Roman Empire’s most active emperors. During his reign, Hadrian visited nearly every province of the Empire and personally surveyed and approved the sites he planned to employ for his projects. In 122 CE, he arrived in Britain and was received in the north by the governor Falco, with whom he would have toured the location of the wall’s construction.

- Hadrian’s construction endeavours are legendary, particularly in Greece, and his propensity for extravagant monuments are highlighted by his titular wall. The work began in stone in the east and progressed westwards across rough terrain to produce a spectacular reflection of Rome’s strength.

- This massive construction project was finished in six years because of the labour of the Roman legions stationed in Britain. Plans for the wall were in place before Hadrian’s arrival to Britain in 122 CE, and construction may have begun earlier than the usual date for the start of work on the wall, maybe as early as 118 CE.

- The wall was originally 9.7 feet (3 metres) wide and 16–20 feet (six metres) high east of the River Irthing, and 20 feet (6 metres) wide and 11 feet (3.5 metres) west of the river, reaching 73 miles (120 kilometres) over the area.

Broad Wall and Narrow Wall

- RG Collingwood, an English historian and archaeologist, found evidence for the presence of a large and narrow wall segment in Hadrian’s Wall.

- He claimed that the original plans for the construction of the wall changed during the construction itself, and the entire width was lowered.

- The broad sections of the wall are approximately 9.5 feet (2.9 metres) wide, while the small areas are roughly 7.5 feet (2.3 metres) wide.

- Some of the narrow sections were discovered to be built on broad foundations, which had been constructed before the designs changed.

The Vallum

- The Vallum is a 10-foot deep ditch-like formation which has two parallel mounds running from north to south of the wall.

- The Vallum and the wall run virtually parallel for almost the entire length of the wall, except at the east end between the forts of Newcastle and Wallsend, where the Vallum may have been thought unnecessary as a barrier due to the close vicinity of the River Tyne.

The wall’s footings, indicating where the Broad Wall and Narrow Wall footings connect

Turf Wall

- The curtain wall was originally constructed from turf from Milecastle 49 to the western termination of the wall at Bowness-on-Solway, probably due to a lack of limestone for constructing mortar. The turf wall was later removed and replaced with a stone wall.

- This occurred in two phases: the first during Hadrian’s reign, and the second following the reoccupation of Hadrian’s Wall following the abandonment of the Antonine Wall, which the Romans built across what is now Scotland’s Central Belt, between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth.

- Except for the passage between Milecastle 49 and Milecastle 51, where the line of the new stone wall is somewhat further north, the line of the new stone wall matches the line of the turf wall.

- The area surrounding Milecastle 50TW was constructed flatly with three to four courses of turf blocks. Milecastle 72 (at Burgh-by-Sands) and maybe Milecastle 53 employed a basal layer of cobbles. Wooden piles were employed if the underlying ground was flooded.

PURPOSE OF THE WALL

- When Hadrian took the imperial throne in 117 CE, there was turmoil and insurrection in Roman Britain and among the peoples of different conquered regions around the Empire, including Egypt, Judea, Libya and Mauretania. These difficulties may have motivated his plan to build the wall and his construction of limes in other parts of the Empire, notably the Limes Germanicus in what is known as modern-day Germany.

- Scholars disagree about how much of a threat the inhabitants of northern Britain truly posed to the Romans and whether there was any economic benefits in defending and patrolling a fixed line of defences like the wall rather than conquering and annexing what is now Northumberland and the Scottish Lowlands and defending the territory with a looser arrangement of forts.

- Hadrian and his counsellors, on the other hand, devised a solution to their issues that has lasted for centuries.

- The wall’s principal purpose was to be a physical barrier against raiders, persons intent on crossing its queue for animals, treasure or enslaved people and returning with their prize.

- The wall supports this interpretation, and pits known as cippi are frequently discovered on the berm or flat area in front of the wall. These pits housed branches or tiny tree trunks entangled with sharpened branches. These would make a wall attack even more difficult. It is the Roman counterpart of barbed wire, used to deter an enemy attack and keep the attackers within range of the defenders’ missiles.

“(Hadrian) was the first to build a wall, eighty miles long, to separate the Romans from the barbarians).” - David J Breeze and Brian Dobson, Hadrian’s Wall, 2004.

- Along the length of the wall, there were 14–17 fortifications and a Vallum that ran parallel to the wall. The conventional understanding of the wall as a defensive work designed to repel attack from the north is based on the site’s composition.

- Roman troops handled these defences, and it has been shown that these soldiers did engage in skirmishes with the locals.

- Hadrian’s Wall allowed the Roman troops to establish additional layers of defence to help defend their region while still maintaining authority over those on their side of the wall.

- A clear border wall like Hadrian’s Wall helped the Romans to prohibit anyone from quickly departing their side of the country, and such an enormously lengthy wall made evasion difficult.

- This was useful not just for defence but also as a kind of propaganda. It displayed the Roman Empire’s great grandeur, particularly that of Hadrian.

“The wall, like other great Roman frontier monuments was as much a propaganda statement as a functional facility…” - Neil Faulkner, The Official Truth: Propaganda in the Roman Empire, 2011.

LIFE INSIDE THE WALL

- The regular soldier stationed on Hadrian’s Wall would typically patrol the structure’s top and keep watch over the several forts and turrets along the way. At its peak, the wall housed approximately 10,000 troops drawn from various auxiliary divisions in the Roman army. The wall’s primary function was defence, but these soldiers were likely expected to serve as border patrol agents.

- Auxiliary soldiers from several countries throughout the Roman Empire lived along Hadrian’s Wall.

- The Roman army’s auxiliary men occupied Segedunum Fort. They lived at the fort for almost 290 years. The unit that lived there when it was first erected was probably the Second Cohort of Nervians from Gallia Belgica (Belgium).

- However, the force that stayed in the fort the longest was the Fourth Cohort of Lingonians from Germania Superior (eastern France).

- Another intriguing aspect of this wall is that the region around it became populated due to its high occupancy and status as a Roman power and authority symbol.

- Farmers and townspeople were divided into zones on either side of the wall. This meant that the local Britons and the Romans who handled the wall were constantly in contact, which resulted in some cultural interchange.

WALL AFTER HADRIAN’S DEATH

- Following Hadrian’s death in 138 CE, the new Emperor, Antoninus Pius, left the wall in a support function, effectively abandoning it. He started construction on the Antonine Wall around 160 kilometres (100 miles) north, across the isthmus spanning west-south-west to east-north-east. An isthmus is a narrow strip of land that connects two larger landmasses and separates two bodies of water.

Bust of Antoninus Pius - This turf wall featured more forts than Hadrian’s Wall and ran 40 Roman miles. This area was later known as the Scottish Lowlands, often the Central Belt or Central Lowlands.

- Because Antoninus could not defeat the northern tribes, when Marcus Aurelius became Emperor in 164 CE, Antoninus reoccupied Hadrian’s Wall as the primary defensive barrier and abandoned the Antonine Wall.

- In 208–211 CE, Emperor Septimius Severus attempted to retake Caledonia and briefly reoccupied the Antonine Wall. The campaign ended in defeat, and the Romans withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall.

- Following Gildas, the early historian Bede wrote:

“[the departing Romans] thinking that it might be some help to the allies [Britons], whom they were forced to abandon, constructed a strong stone wall from sea to sea, in a straight line between the towns that had been there built for fear of the enemy, where Severus also had formerly built a rampart.” - Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum.

- Barbarian invasions, economic collapse and military coups weakened the Empire’s grip over Britain in the late fourth century. By 410 CE, the estimated end of Roman authority in Britain, the Roman administration and legions had vanished, leaving Britain to rely on its defences and government.

- Archaeologists discovered that some wall sections were occupied far into the fifth century. Local Britons may have garrisoned some forts under the command of a Coel Hen figure and former dux, a former Saxon chief or leader.

- Hadrian’s Wall deteriorated, and the stone was reused in various local structures over the years.

- Enough stones taken from Hadrian’s Wall survived in the seventh century to be used in the construction of St Paul’s Church in Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, where Bede was a monk.

- It was included before the installation of the church’s dedication stone, which can still be seen in the church and is dated 23 April 685.

- Much of the wall has since vanished. Long sections of it were used for road construction in the 18th century, particularly by General Wade to build a military road to transfer troops to defeat the Jacobite rising of 1745. The antiquarian John Clayton is responsible for preserving much of what is left.

- To keep farmers from removing stones from the wall, Clayton began purchasing some of the land where the wall existed. In 1834, he began purchasing land around Steel Rigg near Crag Lough.

- Clayton eventually ruled over property stretching from Brunton to Cawfields. This section contained Chesters, Carrawburgh, Housesteads and Vindolanda. Clayton excavated at the forts of Cilurnum and Housesteads and some milecastles.

- Clayton handled the farms he purchased and successfully improved both the land and the livestock. He used the proceeds from his farms to fund restoration projects. Workers were hired to restore sections of the wall up to a height of seven courses.

WORLD HERITAGE SITE

- Hadrian’s Wall was designated a World Heritage Site in 1987, and it became part of the transnational Frontiers of the Roman Empire’s World Heritage Site in 2005, along with sites in Germany.

- Even though Hadrian’s Wall was designated a World Heritage Site in 1987, it remains unsecured, allowing people to climb and stand on it, but this is not encouraged as it could harm the historic structure.

Beacons lit along Hadrian's Wall - On 13 March 2010, a public event called Illuminating Hadrian’s Wall occurred, illuminating the path with 500 beacons.

- On 31 August and 2 September 2012, the wall was illuminated again as part of a digital artwork named Connecting Light as part of the London 2012 Festival.

- A National Trail route that follows the length of the wall from Wallsend to Bowness-on-Solway was opened in 2003. Because of the sensitive nature, walkers can only use the path during the summer.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hadrians_Wall_map.svg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hadrian%27s_Wall,_junction_of_the_Broad_Wall_and_Narrow_Wall_bases.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Antoninus_Pius_Glyptothek_Munich_337_cropped.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Beacons_lit_along_Hadrians_Wall_(geograph_4917923).jpg

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why was Hadrian's Wall built?

Hadrian's Wall was constructed primarily for defensive purposes. It served as a fortified barrier to protect the Roman province of Britannia from raids and invasions by the northern tribes, particularly the Picts and Scots.

- How long is Hadrian's Wall?

Hadrian's Wall is approximately 73 miles (117.5 kilometres) long, stretching across northern England from the North Sea in the east to the Irish Sea in the west.

- Who built Hadrian's Wall?

The wall was constructed by Roman soldiers, primarily the Roman legions stationed in Britannia. Construction of Hadrian's Wall began in 122 CE and was completed around 128 CE during the reign of Emperor Hadrian.