1791 Bill of Rights Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the 1791 Bill of Rights to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Constitutional Convention

- Proposal and Ratification of the Bill of Rights

- Amendments of the Bill of Rights

- Honouring the Bill of Rights

- Application of the Amendments

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the 1791 Bill of Rights!

The newly established United States of America (USA) ratified the Bill of Rights, containing the first ten amendments to its Constitution, which confirmed its citizens’ fundamental rights. The First Amendment of the Bill of Rights ensures Americans their religious, speech and press freedoms and the right to peaceful assembly and petition. These amendments codify themes from earlier documents, including the Magna Carta (1215), the English Bill of Rights (1689), the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), and the Northwest Ordinance (1787).

CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

- Fifty-five delegates from twelve states convened in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention from 25 May to 17 September 1787. Rhode Island was the only state that did not have representation at the convention.

- Though the Articles of Confederation provided the framework for governance since the Declaration of Independence from Britain, many of the political leaders in the United States (US) agreed that establishing a stronger central government was critical to developing US power and potential.

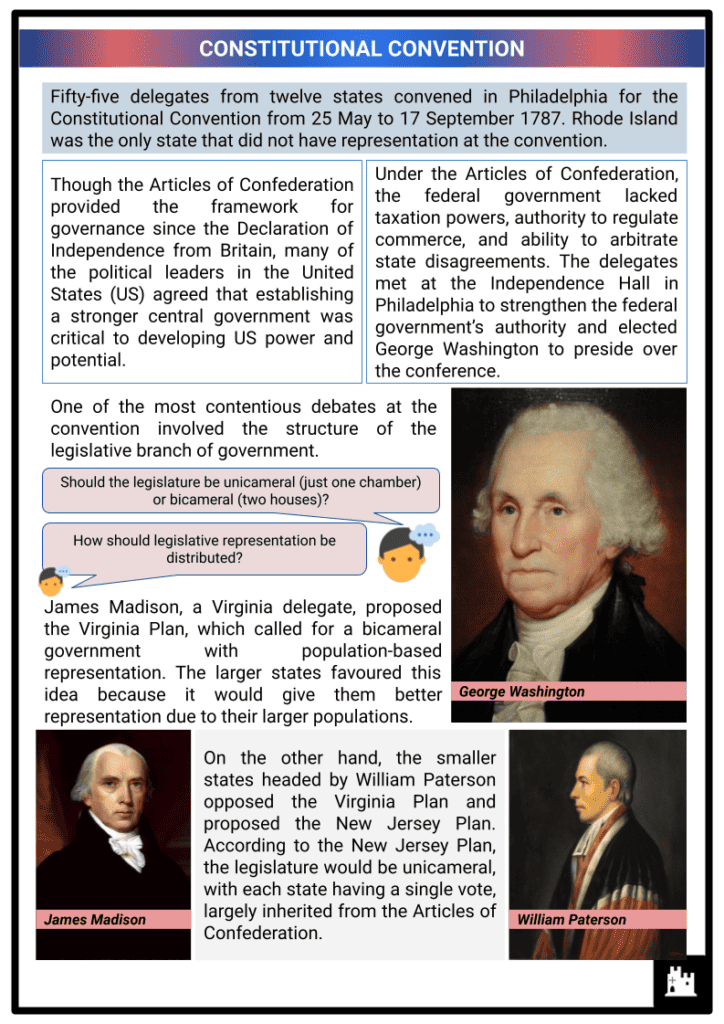

- Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government lacked taxation powers, authority to regulate commerce, and ability to arbitrate state disagreements. The delegates met at the Independence Hall in Philadelphia to strengthen the federal government’s authority and elected George Washington to preside over the conference.

- One of the most contentious debates at the convention involved the structure of the legislative branch of government.

- James Madison, a Virginia delegate, proposed the Virginia Plan, which called for a bicameral government with population-based representation. The larger states favoured this idea because it would give them better representation due to their larger populations.

- On the other hand, the smaller states headed by William Paterson opposed the Virginia Plan and proposed the New Jersey Plan. According to the New Jersey Plan, the legislature would be unicameral, with each state having a single vote, largely inherited from the Articles of Confederation.

Drafting the Constitution

- The delegates eventually used components of both Virginia and New Jersey Plans to form the Connecticut Compromise. The legislative branch would be bicameral, with an upper house called the Senate and a lower house called the House of Representatives.

- The House would be represented based on population, and each state would be assigned two Senate members. The president would exercise executive authority, who the electoral college would elect.

- The government system would be federalist in form, with three distinct branches:

- Executive (President): The President is both the head of state and the head of government, and the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

- Legislative (Congress): was given the authority to levy taxes, declare war, organise an army, regulate interstate trade and write laws to carry out these functions.

- Judicial (Supreme Court): The Supreme Court would resolve interstate conflicts.

- The Compromise also addressed a key issue between northern and southern states about slavery. The northern slaveholding states did not believe that enslaved persons should be counted at all, whereas the southern slaveholding states did. The Three-Fifths Compromise mandated that enslaved men and women be represented in the House at a three-to-five ratio of their actual numbers. As a result, every five people would count as three for legislative representation and taxation.

- Northern delegates, many of whom were rightfully against slavery, viewed the Compromise as an enemy. The southern states threatened to refuse the document’s ratification unless the interests of southern enslavers were protected.

The signing of the Constitution by state delegates by Howard Chandler Christy.

Ratifying the Constitution

- The Constitution had to be ratified – formally adopted by the assemblies of at least nine of the twelve states that had sent delegates to the convention – before it could go into effect. Surprisingly, smaller states were the first to ratify the Constitution despite the heated arguments over legislative representation. The larger states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia were the most vocal opponents to ratifying the document.

- Many opponents of the Constitution said it would establish a huge, intrusive and far-too-powerful federal government that would inevitably reproduce the tyranny that the Patriots fought against during the American Revolution.

New York Circular Letter

- Most of the delegates of the Ratifying Convention in New York were anti-Federalists, and they were unwilling to accept the Massachusetts Compromise.

- Led by Melancton Smith, they were inclined to make New York’s ratification conditional on the preceding introduction of amendments or to insist on the right to separate from the Union if amendments were not swiftly presented.

- After talking with Madison, Alexander Hamilton, a statesman, assured the Convention that Congress would not approve this.

- After the ninth state, New Hampshire, ratified the Constitution, which Virginia quickly followed, it was evident that the Constitution would go into effect with or without New York as a member of the Union.

- The New York Convention recommended ratification as a compromise, believing that the states would call for new amendments using the convention mechanism in Article V rather than making this a condition of ratification by New York.

- John Jay, an American statesman, proposed this scheme in the New York Circular Letter, which was then distributed to all states.

- The legislatures of New York and Virginia passed resolutions calling for the convention to submit modifications that the states had requested. In contrast, several other states delayed the issue for future legislative consideration. Madison drafted the Bill of Rights in part in response to the opposition.

PROPOSAL AND RATIFICATION OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

- The Federalists won the first US Congress, assembled in New York City’s Federal Hall. The 11-state Senate had 20 Federalists and only 2 anti-Federalists, both from Virginia.

- The House was divided into 48 Federalists and 11 anti-Federalists, with the latter hailing from just 4 states: Massachusetts, New York, Virginia and South Carolina.

Patrick Henry - James Madison was among the Virginia delegation to the House.

- In retaliation for Madison’s victory at Virginia’s ratification convention, Patrick Henry and other anti-Federalists who controlled the Virginia House of Delegates manipulated a hostile congressional district for Madison’s planned congressional run and recruited James Monroe to oppose him.

- By proposing amendments through Congress, Madison hoped to prevent a second constitutional convention from undoing the difficult compromises of 1787 and opening up the entire Constitution to reconsideration, risking the dissolution of the new federal government.

- Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson, the US Ambassador to France at the time.

“The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a spirit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty.”

- Jefferson then replied to Madison, saying:

“Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.”

- Historians continue to argue whether Madison regarded the Bill of Rights amendments as necessary and whether he deemed them politically expedient. George Washington addressed revising the Constitution during his inauguration as the nation’s first president on 30 April 1789.

Madison’s proposed amendment

- Madison proposed several constitutional amendments to the House of Representatives for debate. He suggested introducing introductory wording emphasising natural rights in the preamble.

- Another would extend the Bill of Rights provisions to both the states and the federal government. Several attempted to defend individual personal rights by limiting Congress’s different constitutional authorities.

- Madison thoroughly reviewed different sources in drafting the amendments. For example, the English Magna Carta of 1215 inspired the right to petition and trial by jury. The English Bill of Rights of 1689 provided an early basis for the right to keep and bear arms and prohibited cruel and unusual punishment.

- Existing state constitutions, however, had the biggest impact on Madison’s drafted amendments. Many of his revisions, including his proposed new preamble, were based on anti-Federalist George Mason’s 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Madison also searched for ideas agreed upon by numerous states to decrease future ratification opposition.

- The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted to declare men’s inherent rights, including the right to modify or abolish inadequate government.

- Federalist delegates were quick to criticise Madison’s suggestion, saying that any attempt to change the new Constitution so soon after its adoption would create the appearance of instability in the government.

- Following a procedural process in which the revisions were initially forwarded to a select committee for reconsideration, the Senate agreed to take Madison’s motion up as a full body beginning on 21 July 1789.

- The committee’s 11 members made major revisions to Madison’s 9 suggested amendments, including removing most of his preamble and inserting the phrase freedom of speech and the press.

- On 24 August 1789, the revisions were adopted and transmitted to the Senate, altered and reduced from 20 to 17.

- The Senate further revised these modifications, making 26 alterations of its own. Madison’s proposal to apply sections of the Bill of Rights to both the states and the federal government was rejected, and the 17 amendments were whittled down to 12, which were passed on 9 September 1789.

- In contrast, many anti-Federalists were now opposed, realising that Congressional adoption of these amendments would significantly reduce the possibilities of a second constitutional convention. Anti-Federalists like Richard Henry Lee contended that the Bill preserved the most problematic parts of the Constitution, like the federal judiciary and direct taxation.

AMENDMENTS OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

- The first ten amendments were submitted by Congress in its first session in 1789. After being ratified by three-quarters of the legislatures in the various states, they became a part of the Constitution on 15 December 1791 and are known as the Bill of Rights.

- The First Amendment prohibits the government from interfering with the rights to free speech, peaceful assembly and religious exercise.

- The Second Amendment proclaims that properly organised militias are a bulwark of liberty and that the right to keep and bear arms is guaranteed.

- The Third Amendment prohibits soldiers from being quartered in private residences, an immensely divisive topic that drove the colonies to war with Great Britain.

- The Fourth Amendment protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures of private property.

- The Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Amendments establish several legal and criminal justice guarantees, including the right to a jury trial; protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy (being tried twice for the same offence); the right to due process; the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment; and the right to face one’s accuser, obtain legal counsel, and be informed of all criminal charges.

- The Ninth Amendment recognises that the previous eight amendments provide a partial list of all the rights and protections given to people.

- The Tenth Amendment specifies that any powers not expressly granted to the federal government in the Constitution will be transferred to the states. This strengthened the notion of federalism, or separation of powers, by assuring that the federal government could not assume rights and functions not expressly granted in the Constitution.

HONOURING THE BILL OF RIGHTS

- Washington had 14 original handwritten copies of the Bill of Rights, one for each of the initial 13 states and one for Congress. The Georgia, Maryland, New York and Pennsylvania copies went missing.

- After 50 years on exhibit, the casing had traces of corrosion, but the documents appeared in good condition. As a result, on 17 September 2003, the casing was updated, and the Rotunda was rededicated. In his dedicatory remarks, US President George W Bush stated:“The true [American] revolution was not to defy one earthly power, but to declare principles that stand above every earthly power—the equality of each person before God, and the responsibility of government to secure the rights of all.”

APPLICATION OF THE AMENDMENTS

- The Bill of Rights had minimal judicial impact for the first 150 years of its existence. Gordon S Woods, an American historian, stated: “After ratification, most Americans promptly forgot about the first ten amendments to the Constitution.”

- Historian Richard Labunski traces the Bill’s legal inactivity to three factors:

- Culture of tolerance

- The Supreme Court focuses on intergovernmental balances of power.

- The Bill initially only applied to the federal government

- However, most of the Bill’s provisions were applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment in the 20th century, a process known as incorporation, beginning with the freedom of expression clause in Gitlow v. New York (1925). The Supreme Court declared in Talton v. Mayes (1896) that constitutional safeguards, including the articles of the Bill of Rights, do not apply to the conduct of Indigenous peoples’ governments.

- By providing deeply established legal protection for diverse civil liberties and fundamental rights, the Bill of Rights establishes legal restrictions on the powers of governments. It operates as an anti-majoritarian/minoritarian safeguard.

- In the decision of West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Supreme Court determined that the founders intended the Bill of Rights to place some rights beyond the reach of majorities, ensuring that some liberties would persist past political majorities.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the 1791 Bill of Rights?

The 1791 Bill of Rights refers to the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution, which

were ratified on 15 December 1791. These amendments guarantee fundamental rights and protections to American citizens. - What rights are protected by the 1791 Bill of Rights?

The 1791 Bill of Rights protects various rights, including freedom of speech, religion, and the press, the right to bear arms, protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, the right to a fair trial, and protection against cruel and unusual punishment, among others.

- Why were the Bill of Rights amendments added to the Constitution?

The Bill of Rights was added to address concerns raised by Anti-Federalists, who feared that the original Constitution did not provide enough protections for individual liberties. The amendments were added to ensure the rights and freedoms of American citizens.