Mary Anning Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Mary Anning to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early childhood

- Family specimen business and fossil discoveries

- Later years

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Mary Anning!

Mary Anning was born in 1799 to a poverty-stricken family in Lyme Regis in Dorset. She received limited education but was able to teach herself geology, anatomy and scientific illustration. Her exceptional skills in fossil hunting proved significant to the careers of many British scientists, as well as the early development of palaeontology. Her discoveries included the first correctly identified ichthyosaur skeleton, the first two almost complete plesiosaur skeletons, the first pterosaur skeleton found outside Germany and fish fossils.

Early childhood

- Born in Dorset, England on 21 May 1799, Mary Anning was the only surviving daughter of the cabinetmaker and carpenter Richard Anning and Mary Moore. She was named after her eldest sister, who died at age four. Many of her siblings died, and only her and her older brother Joseph survived to adulthood.

- The family lived in Lyme Regis in a house built on the town’s bridge, which was very close to the sea. They were religious Dissenters, attending the Dissenter chapel on Coombe Street, whose worshippers later became known as Congregationalists.

- It was at the Congregationalist Sunday school where Anning received her limited education. She owned a bound volume of the Dissenters’ Theological Magazine and Review, which she valued highly.

- The family’s religious beliefs had an impact on their social and economic status. As they did not adhere to the Articles of the Church of England, many opportunities were denied to them, such as studying in certain universities, taking certain positions in the army, and pursuing several professions.

- Following the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, the English were urged to holiday near home rather than abroad. The family’s place of residence, Lyme Regis, became a popular seaside resort for the wealthy and middle-class tourists.

- This presented a potential opportunity for the residents of the area, who were in need of additional income for their families. The locals collected fossils and sold them to the tourists. The area is especially rich in ammonites and belemnites.

- Anning’s father mined the coastal-cliff side fossil beds near the town, often bringing Anning and Joseph to these expeditions. He also taught the children how to clean their finds. They then offered the fossils to tourists on a table outside their home. The sale supplemented the family income.

- Anning’s father had been ill due to tuberculosis and previous injuries. When he died in 1810, the family, who had been living in poverty, was left with debts and no savings. They were forced to apply for poor relief and rely mainly on charity.

Family specimen business and fossil discoveries

- Fossil collecting remained a popular pastime in the early 19th century. It gradually developed into a science as fossils proved significant to geology and biology. Anning, as well as her mother and brother, who were skilled fossils hunters, continued selling their finds to collectors and scholars in order to supplement their limited resources.

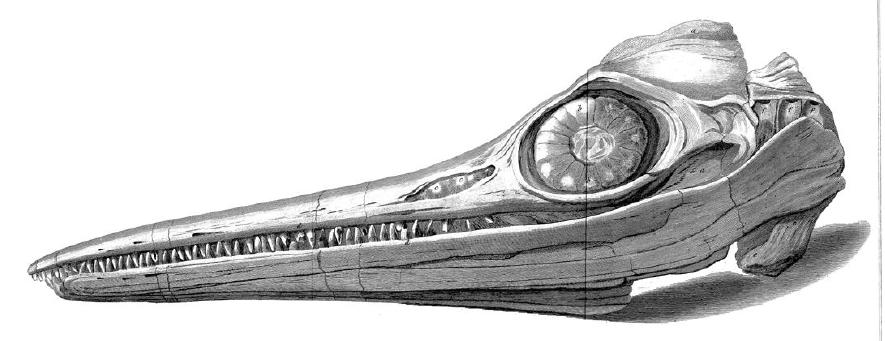

- In 1810, Anning’s brother Joseph found a strange-looking fossilised skull. After several months of digging, Anning, aged 12, discovered the rest of the 5.2-metre-long skeleton. This was the family’s first notable fossil find.

- They were paid £23 for it by Henry Hoste Henley of Sandringham, who then sold it to a famous collector.

- Scientists initially thought the specimen was a crocodile. It was studied for years and eventually named Ichthyosaur.

- Between 1815 and 1819, Anning excavated several other ichthyosaur fossils of varying sizes.

- In 1817, the wealthy Lincolnshire fossil collector Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch began to buy several specimens from the Annings. He became the family’s keenest customer.

- In 1820, the family was in a dire situation, having made no substantial discoveries.

- Birch was perplexed upon discovering the family’s impoverished circumstances, and so decided to auction off the fossil collection he purchased from them, with the intention to donate its proceeds to the family.

- The auction brought in a significant amount of money, which seems to have helped improve the Annings’ financial footing. Additionally, the three-day auction held in London raised the family’s profile within the geological community.

- Anning’s mother initially assumed the main responsibility of the fossil business after 1810. Meanwhile, Joseph continued fossil hunting until at least 1825. Soon, Anning took the leading role in the family business.

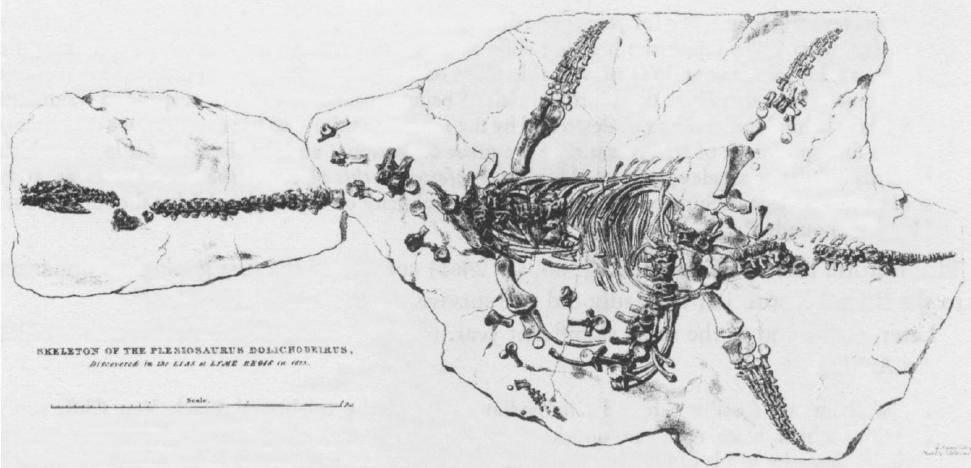

- In 1821, a specimen obtained by Birch, most probably from Anning, was named and described to be the genus Plesiosaurus. While the paper gave credit to Birch, it did not mention who discovered it.

- In 1823, Anning found a much more complete Plesiosaur skeleton, which was rumoured to be fake due to its unprecedented 35-vertebrae long neck.

- The French anatomist Georges Cuvier reviewed Anning’s drawing of the second skeleton and suggested that it was a fraud.

- This led to a special meeting of the Geological Society of London early in 1824, to which Anning was not invited. At the time, women were not allowed to join the Society, or even attend meetings as guests.

- The meeting concluded that the skeleton was legitimate, and Cuvier later admitted his mistake.

- In 1826, Anning had saved enough money to buy a house with a glass storefront window for her shop, Anning’s Fossil Depot.

- The business was well-known by this time, and many collectors and geologists from Europe and America visited her at Lyme to collect fossils or discuss anatomy and classification.

- Although she lacked formal scientific training, she taught herself geology, anatomy and scientific illustration. This, coupled with her local area knowledge and classification skills, earned her a reputation among the predominantly male and upper-class palaeontology community.

- Despite this reputation, she was not given full credit by the scientific community for many of the fossils she excavated.

- In 1826, Anning found what appeared to be a chamber containing dried ink inside a belemnite fossil. She noticed how this resembled the ink sacs of modern squid and cuttlefish. This led to the conclusion that belemnites had also used ink for defence.

- In 1828, Anning discovered a partial skeleton of a pterosaur, which was described as Pterodactylus macronyx and later called Dimorphodon macronyx.

- It was the first pterosaur skeleton to be found outside Germany. It sparked public sensation when it was shown at the British Museum.

- The English geologist, William Buckland, credited her with the discovery of the specimen in his paper. He recognised Anning’s skills again when he published about the bezoar stones he named coprolites, which were fossilised faeces of ichthyosaurs.

- In 1829, Anning uncovered a fossil fish, Squaloraja, which was thought to be a member of a transition group between sharks and rays.

- While Anning was more knowledgeable about fossils and geology than many of the prominent fossil collectors to whom she sold, it was always the gentlemen geologists who published the scientific descriptions of the specimens she discovered. She was also often overlooked and not properly credited for her efforts. Nevertheless, she continued assisting famous scientists of the time in their hunting expeditions.

Later years

- By 1830, the demand for fossils had declined, and Anning had had no recent major finds. This left her under financial strain. The geologist Henry De la Beche helped her by commissioning a lithographic print of his watercolour paintings based largely on fossils found by Anning. This was called the Duria Antiquior, which became the first scientifically minded paleoart. The proceeds of the prints were given to Anning.

- Later that year, Anning finally made another major find, a skeleton of a new type of plesiosaur, which sold for £200.

- Around this time, she left the Congregational Church and began attending the Anglican Church. This decision came about following a change in leadership in her previous church, and partly due to the greater social respectability of the established church.

- In 1835, she again faced financial difficulty after losing much of her life savings in a bad investment.

- Her friend Buckland was determined to help her, and so convinced the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the British government to grant her an annuity, known as a civil list pension, in exchange for her numerous contributions to the science of geology. Anning had some financial security thanks to the £25 annual pension.

- In the last few years of her life, her fossil work was affected by illness.

- In 1846, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer, the Geological Society of London raised funds from its members to assist her in her expenses.

- On 9 March 1847, she died at the age of 47. She was buried in the churchyard of St Michael’s, the local parish church.

- De la Beche, president of the Society, eulogised her in his annual address, which was also published in the Society’s quarterly transactions.

- In 1850, a stained-glass window in Anning’s memory depicting the six corporal acts of mercy was unveiled at St Michael’s Church. In 1902, the Lyme Regis Museum was constructed on the site of Anning’s former home. In 2010, the Royal Society recognised her as one of the ten most influential women scientists in British history. In 2022, the statue of Anning was unveiled in Lyme Regis on the 223rd anniversary of her birth.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Mary Anning?

Mary Anning was a British fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who made significant contributions to the field of palaeontology in the early 19th century.

- What were Mary Anning's most famous discoveries?

Mary Anning discovered the first complete Ichthyosaur skeleton in 1811 when she was just 12 years old. She later discovered the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton in 1823 and the first British Pterosaur fossil in 1828. These discoveries revolutionised the scientific understanding of prehistoric marine life.

- What challenges did Mary Anning face as a female scientist in the 19th century?

Mary Anning faced numerous challenges due to her gender and social status. As a woman, she was excluded from academic institutions and scientific societies, and she faced discrimination and scepticism from male scientists who were reluctant to accept her findings.