Patrick Henry Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Patrick Henry to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

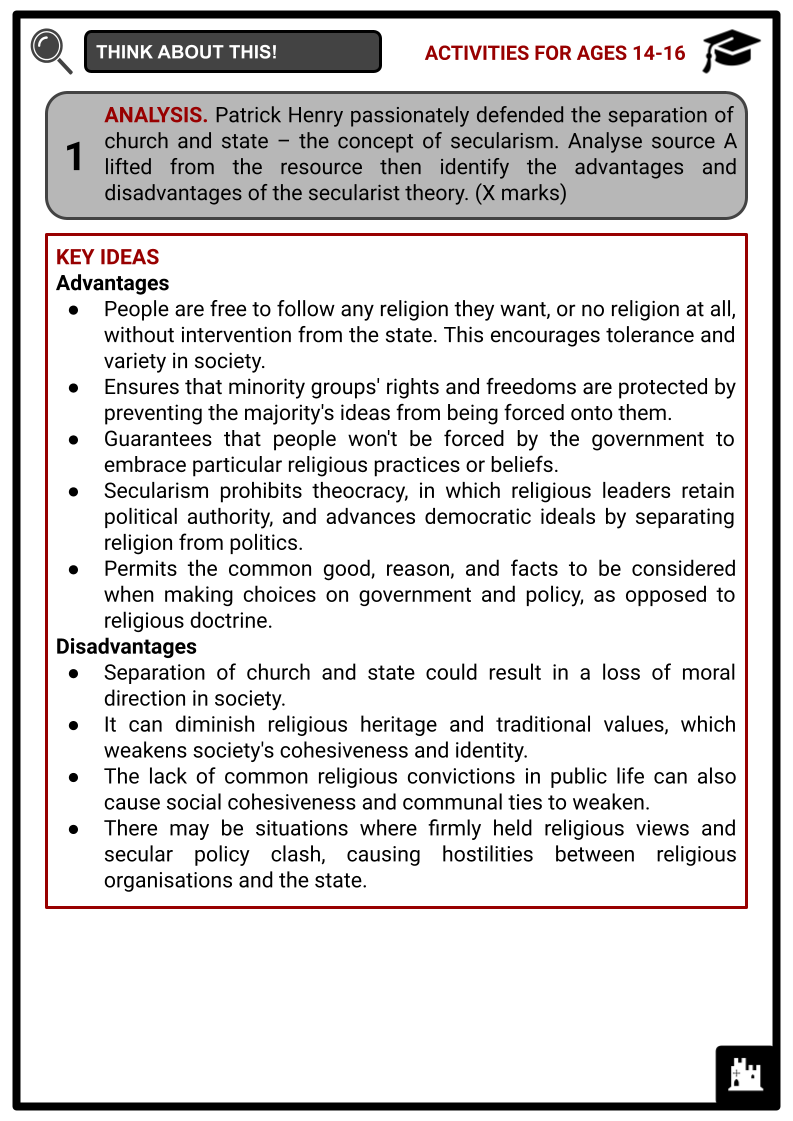

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Early Life

- Lawyer and Politician

- Later Life and Death

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Patrick Henry!

American Revolutionary leader Patrick Henry is best known for his famous quote, "Give me liberty or give me death!" Henry was a key figure in the radical opposition to the British government and only accepted the new federal government after the Bill of Rights was passed, for which he bears much of the blame. Henry's impassioned and compelling remarks served as a catalyst for the American Revolution.

EARLY LIFE

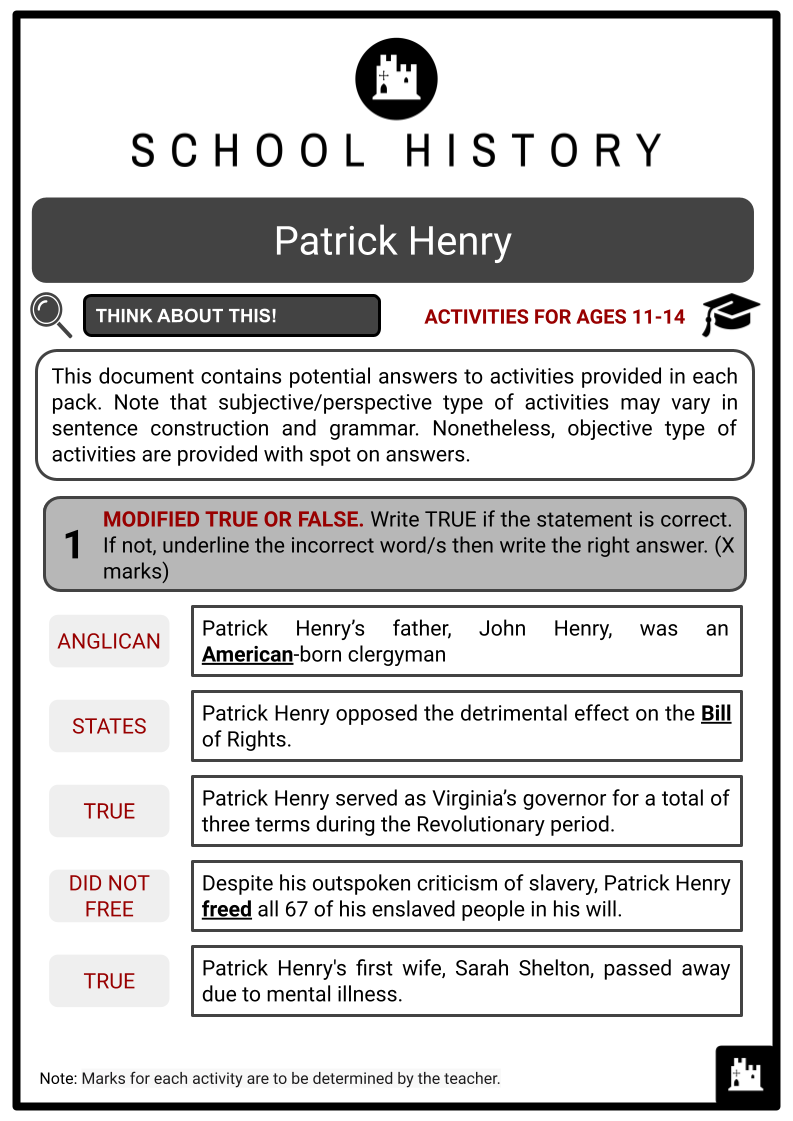

- Patrick Henry was born on 29 May 1736, on his family's property in Studley, Hanover County, Virginia. John Henry, his father, was an immigrant from Aberdeenshire, Scotland, who studied at the University of Aberdeen's King's College before moving to Virginia in the 1720s. After moving to Hanover County in 1732, John Henry married Sarah Winston Syme, a prosperous widow descended from a well-known English-American family in the neighbourhood.

- Henry, the second of nine children, learned a lot from his father, an Anglican clergyman, and his uncle, a university graduate from Scotland. He learned to play the flute and fiddle as a young child. He might have taken inspiration for his excellent oratory skills from his uncle's and other religious speeches. On occasion, Henry would accompany his mother to services conducted by travelling Presbyterian ministers.

- Henry was exposed to a variety of religions at a young age because he was raised during Virginia's Great Awakening.

- Even though he remained an Anglican, he picked up the idea from people like Samuel Davies that social action should be motivated by faith and that speeches should emotionally resonate with listeners.

- Though he was uncomfortable with the Anglican denomination in Virginia, he was greatly impacted by religion.

- He defended religious liberty, called for harmony among Christian groups, and denounced the evils of Virginia, especially intolerance and slavery.

- He passionately defended the separation of church and state before the Virginia Ratifying Convention in 1788, saying that everyone should have the freedom to practise their religion without interference and that religious convictions should be the result of personal conviction rather than force.

- Henry took over his father's store at the age of fifteen. Henry experienced his first taste of failure when his business failed. In 1754, he married Sarah Shelton, a local innkeeper's daughter. Henry got some farmland as part of his wife's dowry. For three years, he attempted to cultivate tobacco there, but his new endeavour didn't work out well. Henry and his spouse lost their farmstead to fire in 1757. After that, he assisted his father-in-law in running a tavern while pursuing legal studies. He obtained his law licence in 1760. Together, he and Shelton had six children.

LAWYER AND POLITICIAN

- The Virginia Colony approved a statute altering the way church clergy were compensated, resulting in a financial loss for the ministers. Henry gained notoriety as a lawyer and persuasive speaker with the 1763 case known as "Parson's Cause." A Virginia clergyman filed a lawsuit seeking compensation after King George III reversed the statute, and he was successful. When the matter was brought before a jury to determine damages, Henry stood up against the clergyman. By drawing attention to the legal decision's connection to royal meddling in colonial affairs and greed, he persuaded the jury to give the lowest possible award—one farthing, or one penny.

- Henry was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1765. He established himself as one of the first critics of British colonial policies.

- Henry stood out against the Stamp Act of 1765 during the discussion of the legislation, which essentially taxed all printed paper used by the colonists. He argued that the colony should be the sole entity with the authority to tax its people.

- Henry remained unaffected despite some members of the assembly screaming that his remarks were treasonous.

- His recommendations for resolving the issue were printed and disseminated to other colonies, which contributed to the growing unrest against British control.

- Henry was a driving force behind the escalating uprising against Britain and possessed a unique capacity to communicate his political philosophy in terms that the average person could understand. In 1774, he was chosen to attend the Continental Congress in Philadelphia as a delegate. He met Samuel Adams there, and the two of them fanning the flames of revolution.

- Patrick Henry urged the colonies to band together throughout the proceedings to oppose British control, saying, "I am an American, not a Virginian. The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more."

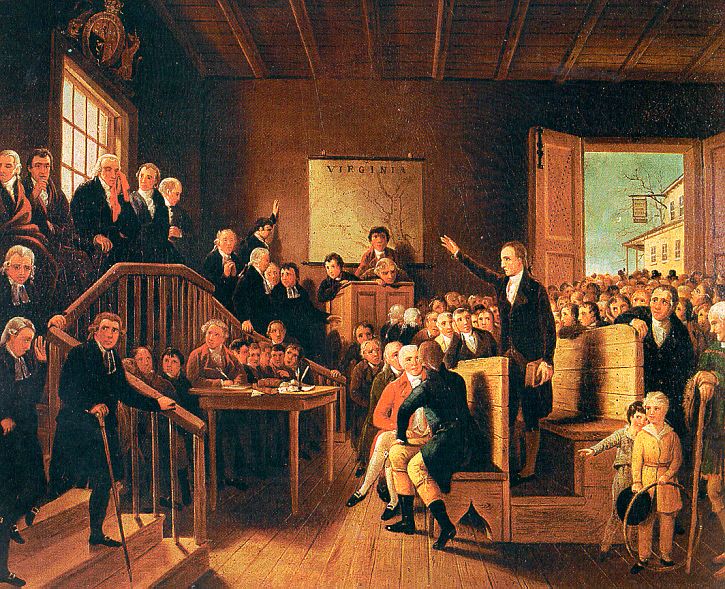

- Henry delivered what is arguably the most well-known speech of his career the following year. In March of 1775, he was present at the Virginia Convention. The committee was discussing whether to use force or peaceful means to end the problem with Great Britain. Henry sounded an appeal to arms, saying, "Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? ... Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!"

- The American Revolution got underway quite quickly after the first guns were fired. After six months, Henry resigned from his position as Virginia's armies' commander-in-chief. He assisted in drafting the state's constitution in 1776, emphasising statesmanship. In the same year, Henry was elected as the first governor of Virginia.

- Henry offered the revolt his full support in his capacity as governor. He assisted George Washington in supplying troops and gear. Additionally, he dispatched troops from Virginia, under George Rogers Clark, to expel British forces from the northwest. Henry resigned from the governorship in 1779 after serving three terms. He continued to participate in politics as a state assembly member. Henry was governor for two more terms in the middle of the 1780s.

- Henry was a staunch opponent of federalism, seeing a strong federal government as a precursor to the kind of tyranny the colonists had endured under British rule. He declined a chance to go to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in 1787. Even after the convention, when he received a draft of the Constitution from Washington, his opposition to this renowned instrument remained.

- When it came time for Virginia to ratify the Constitution, Henry opposed it, believing that its ideas would have a detrimental effect on states' rights and labelling them "dangerous." Many Federalists, including James Madison, were concerned that Henry would succeed in his anti-Constitution campaign given the strong support he enjoyed in Virginia. Henry's argument did not, however, win over most legislators, as the text was confirmed by a vote of 89 to 79.

LATER LIFE AND DEATH

- Henry quit his job in government in 1790. He made the decision to go back to practising law, and his practice flourished. Henry was often nominated to high-ranking posts over the years, including Attorney General, Secretary of State, and Justice of the Supreme Court, but he declined each one. Rather than wrangling with the political landscape, he would have rather been with his second wife, Dorothea, and their numerous children. In 1775, his first wife passed away following a struggle with mental illness.

- The relatively difficult relationship between Patrick Henry and George Washington during the ratification discussions started to improve in 1794.

- Henry rejected Washington's offers of a Supreme Court seat, Secretary of State, and ministerial offices, citing family responsibilities, even though he supported Washington over Jefferson and Madison.

- Henry resisted attempts by Virginia Governor "Light-Horse" Harry Lee to nominate him to the Senate in order to preserve his standing in the state.

- Henry lived out his final years at "Red Hill," his plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia. Henry was eventually convinced to run for office in 1799. By this time, he had switched political parties and joined the Federalists. Henry pushed for a seat in the Virginia legislature at Washington's encouragement. Despite winning the position, he passed away before taking office. He died at his Red Hill residence on 6 June 1799.

- Despite never having been elected to the federal government, Patrick Henry is regarded as one of the greatest revolutionary leaders. His titles include "Voice" and "Trumpet" of the American Revolution. His strong speeches sparked a revolt, and his political initiatives outlined plans for a new nation.

- Henry left his wife and his six sons equal shares of his property and 67 enslaved people in his testament. Despite his protests against tyrannical enslavement and his countless remarks criticising the system of slavery itself, he did not free any of his enslaved people.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who was Patrick Henry?

Patrick Henry (1736–1799) was an American attorney, orator, and politician best known for his stirring speeches advocating for American independence from British rule.

- What is Patrick Henry famous for?

Patrick Henry is famous for his impassioned speech on 23 March 1775 in Richmond, Virginia, in which he proclaimed, "Give me liberty, or give me death!" This speech is considered one of the most influential in American history.

- What were Patrick Henry's views on slavery?

Patrick Henry enslaved people and was a product of his time. While he expressed some reservations about the institution of slavery, particularly its moral implications, he did not actively work towards its abolition and was not a vocal abolitionist.