Bechuanaland Protectorate Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Bechuanaland Protectorate to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Expansion of the British Empire in Africa

- Establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate

- Development in the Bechuanaland Protectorate

- Path to independence

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Bechuanaland Protectorate!

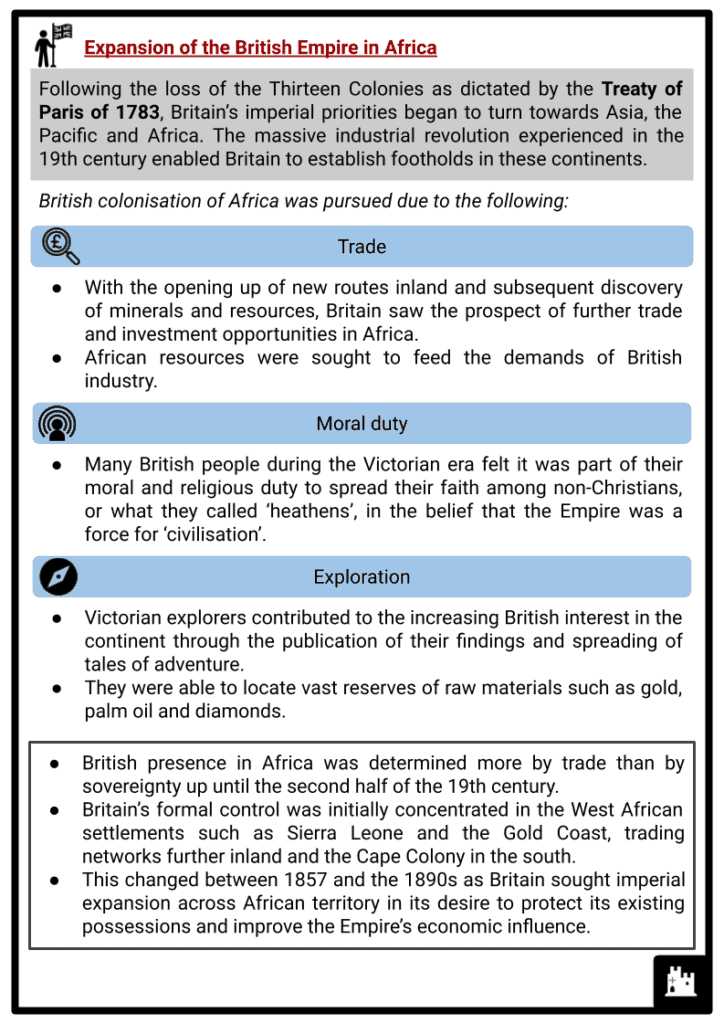

The Bechuanaland Protectorate was established by Britain in March 1885 with the intention to protect the huge landlocked region in Southern Africa against further expansion by Germany, Portugal or the Boers. While Britain was generally responsible for the administration of the territory, the Tswana people were granted self-government. Under British rule, administrative reform and economic development were limited. The protectorate gained its independence in September 1966 as the Republic of Botswana following a surge in nationalist spirit in the region.

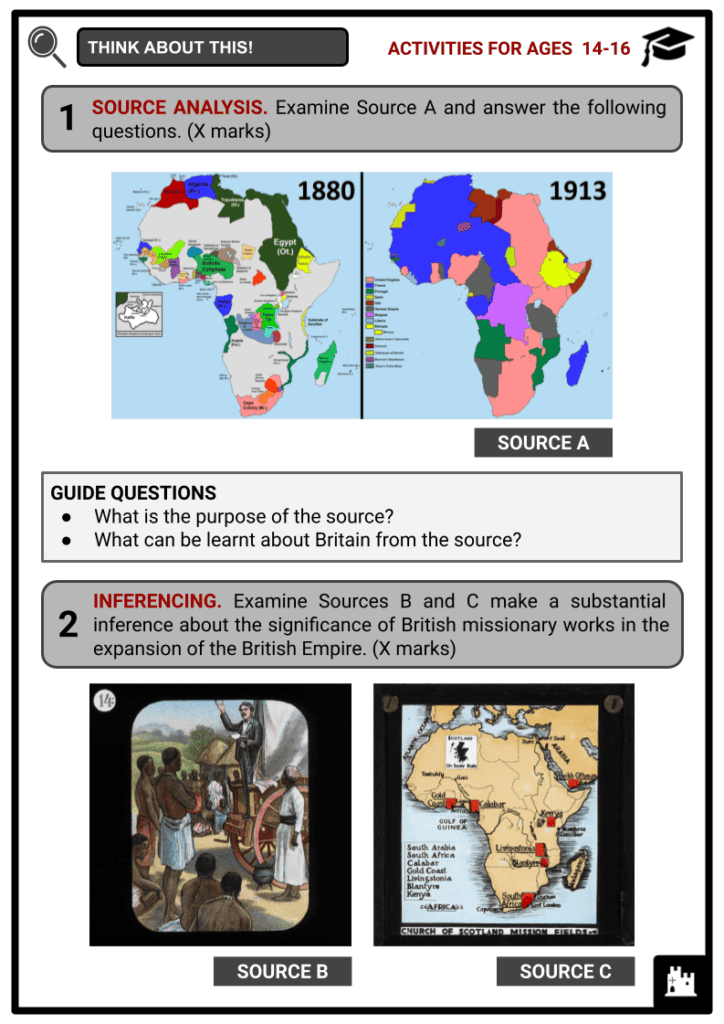

Expansion of the British Empire in Africa

- Following the loss of the Thirteen Colonies as dictated by the Treaty of Paris of 1783, Britain’s imperial priorities began to turn towards Asia, the Pacific and Africa. The massive industrial revolution experienced in the 19th century enabled Britain to establish footholds in these continents.

British colonisation of Africa was pursued due to the following:

Trade

- With the opening up of new routes inland and subsequent discovery of minerals and resources, Britain saw the prospect of further trade and investment opportunities in Africa.

- African resources were sought to feed the demands of British industry.

Moral duty

- Many British people during the Victorian era felt it was part of their moral and religious duty to spread their faith among non-Christians, or what they called ‘heathens’, in the belief that the Empire was a force for ‘civilisation’.

Exploration

- Victorian explorers contributed to the increasing British interest in the continent through the publication of their findings and spreading of tales of adventure.

- They were able to locate vast reserves of raw materials such as gold, palm oil and diamonds.

- British presence in Africa was determined more by trade than by sovereignty up until the second half of the 19th century.

- Britain’s formal control was initially concentrated in the West African settlements such as Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast, trading networks further inland and the Cape Colony in the south.

- This changed between 1857 and the 1890s as Britain sought imperial expansion across African territory in its desire to protect its existing possessions and improve the Empire’s economic influence.

British Expansion in Africa (1857–1890)

- Britain found a particular rival in France, which led to the formalisation of control of the former in areas where British traders had been operating. This was done by chartering companies including the Royal Niger Company, the Imperial British East Africa Company and the British South Africa Company to enforce British claims in the continent.

Establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate

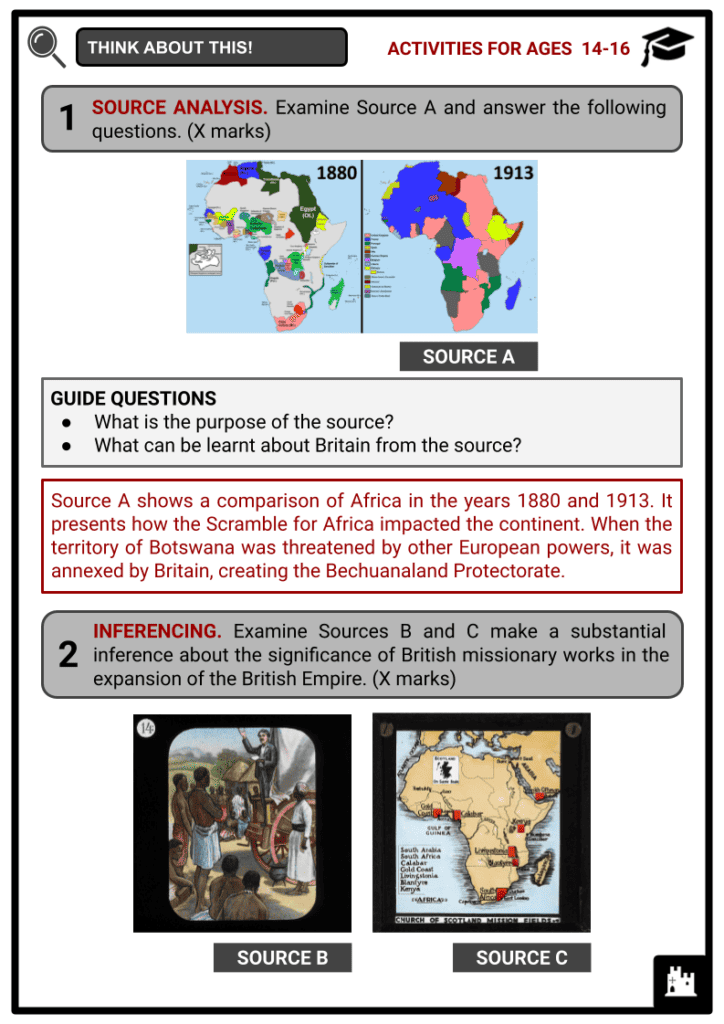

- Following the conclusion of the Batswana-Boer Wars in the first half of the 19th century, trade thrived in Southern Africa owing to the consequent peaceful conditions. New roads to the Cape Colony enabled British missionaries and traders to access the huge landlocked region in Southern Africa that later became the Bechuanaland Protectorate, modern-day Botswana. In fact, the Lutheran and the London Missionary Society proponents both became constituted in the region by the 1850s.

- As the influence of British missionaries in the region grew stronger, several Tswana rulers and people accepted Christianity and a huge deal of Tswana customary law was impacted.

- In the late 1860s, many white miners and prospectors came to the territory to begin deep gold mining at Tati.

- The gold rush, however, was short-lived, and the diamond mines at Kimberley near the region came to be Southern Africa’s first great industrial area from 1871.

- The Scramble for Africa in the 1880s saw South-West Africa colonised by the German Empire.

- Meanwhile, the territory of Botswana was annexed by Britain by using its missionary and trade connections with the Tswana states.

- This was to keep the roads through the region open for British expansion and to link the Cape Colony to British territories further north.

- In 1885, the Scottish missionary John Mackenzie called for British protection of the Tswana people from Boer freebooters encroaching on their territory from the south.

- This influenced the British government to despatch a military expedition led by Sir Charles Warren to South Africa to assert British sovereignty over the contested territory.

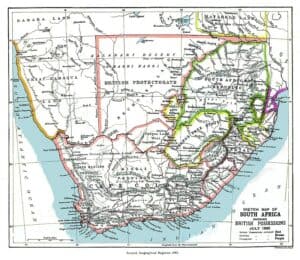

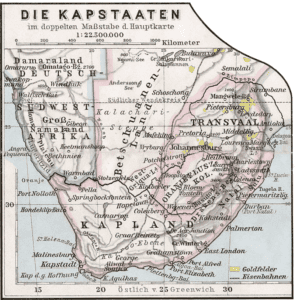

A German map showing the undivided Bechuanaland territory - After Warren finalised several treaties with Tswana rulers, the Bechuanaland Protectorate was established in March 1885. In September, the territory south of the Molopo River was declared the Crown colony of British Bechuanaland. In 1890, the Bechuanaland Protectorate was extended to the Tawana and the Chobe River.

Development in the Bechuanaland Protectorate

- Three main Tswana peoples, the Bamangwato, the Bakwena and the Bangwaketse, occupied the Bechuanaland Protectorate. A number of minor groups like the Bamalete and the Bakhatla, and the descendants of the original dwellers of the area, such as the Bushmen and Makalaka, also lived in the protectorate. The local Tswana rulers were initially left in power with the British administration confined to the police force to defend the borders against other European colonial ventures.

- The 1890s saw the protectorate split into eight different reserves, with moderately small amounts of land designated for white settlement.

- British colonial expansion was privatised in the form of the British South Africa Company (BSAC). In the early 1890s, the British government decided to turn over the protectorate to the BSAC. However, this plan was opposed by the Tswana leaders, who then sent a delegation to London in 1895 to protest.

- As a result, the protectorate remained under the British Crown but the leaders had to submit to the BSAC the right to build a railway to Rhodesia through their lands.

- From 1895, the administrative capital of the protectorate was at Mafeking, the capital city of the North-West province of South Africa. This meant that the capital was outside the territory, creating an unusual situation. This also reflected that the British government intended the protectorate as a temporary expedient. Moreover, as one of the High Commission Territories, the British office of the High Commissioner for Southern Africa was responsible for its administration, with the major Tswana groups granted self-government. The office was initially held by the governor of the Cape Colony, then by the Governor-General of South Africa.

- The High Commission Territories which included the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Basutoland (present-day Lesotho) and Swaziland (present-day Eswatini) were not included in the Union of South Africa formed in 1910. Provision was made for their later incorporation. Investment and administrative development within the protectorate were limited.

- Consequently, the Bechuanaland Protectorate appeared to be a mere appendage of South Africa, providing migrant labour and the rail transit route to Rhodesia.

- In 1911, the Tati district, an area where gold was discovered in the 1860s, was annexed to the protectorate via the Tati Concessions Land Act with a special agreement to uphold rights of access for Rhodesian Railways.

- When the First World War broke out, concerns about the threat from the neighbouring German South-West Africa and any overflow of aggression into the protectorate emerged. Consequently, the Resident Commissioner established a Volunteer Reserve of 100 men to assist the police in administering the territory and quelling any unrest that might occur during the conflict. A small German raid on a border post and a rebellion in South Africa took place which were both suppressed by a combination of British and local forces.

- The First World War saw the enthusiastic contribution of the inhabitants of the protectorate to war funds by supplying 100 pairs of socks knitted for troops abroad.

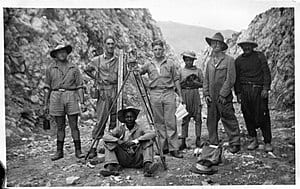

A mixed group of Lebanese labourers, Australian and AAPC servicemen in Lebanon, 1942 - In 1920, two advisory councils to represent both Africans and Europeans were created as a result of an expansion of British central authority and the advancement of local government. The African Council comprised eight leaders of the Tswana groups and some elected members.

- In the 1930s, attempts to reform administration and to commence mining and agricultural development were extremely opposed by Tswana leaders as they believed that such would only strengthen colonial control and white settlement. In 1934, there were proclamations that oversaw tribal rule and powers.

- Following the British entry into the Second World War, men from the High Commission Territories were recruited into the African Auxiliary Pioneer Corps (AAPC) labour unit. Mobilisation for the AAPC started in late July 1941. About 10,000 men from the Bechuanaland Protectorate enlisted to serve overseas.

- This was made possible as Tswana rulers proved willing to provide men for the British Army. During the North African, Dodecanese and Italian campaigns, the AAPC provided logistical support to the Allied war effort while some relieved British field artillery units of their duty. Moreover, the protectorate also invested in disease control and livestock improvement during the conflict.

- After the war, the protectorate reverted to its pre-war role as an appendage of South Africa. In 1947, King George VI of Britain and his family visited the territory to thank the people for their wartime service.

- Successive governments of the Union of South Africa sought to have the High Commission Territories transferred to their jurisdiction, but the British government kept delaying. The National Party’s economic policies seemed to threaten British investments in South Africa at a time when colonial possessions were of great assistance to Britain in funding its outstanding balance. At the same time, nationalists renewed their demand for the incorporation of Lesotho, Botswana and Swaziland into South Africa.

Path to independence

- Developments in South Africa in the 1950s ended any prospect of Britain or the High Commission Territories agreeing to incorporation. As it came to be clear that the three territories had to be developed towards political and economic self-sufficiency, limited funds were made available for the provision of social services, education, soil conservation and infrastructure development.

- In 1951, a European-African advisory council was set up.

- From 1952, political movements began to be organised by the supporters of Seretse Khama, an heir to the chieftainship of the ruling Tswana group in the Bechuanaland Protectorate who had been in exile in Britain due to his marriage to a British woman. There also emerged a nationalist spirit even among older Tswana leaders.

- In 1956, Khama and his English wife were permitted to return to the protectorate as private citizens after he had relinquished the chieftainship.

- He started to participate in local politics and was elected to the tribal council as its secretary in 1957.

- In 1960, the Bechuanaland People’s Party was founded.

- In 1961, a consultative legislative council was formed after limited national elections.

- In the same year, Khama along with other delegates to the African Advisory Council set up the Bechuanaland Democratic Party (BDP).

Flag of Botswana - His exile worked to his advantage as it gave him an increased credibility with an independence-minded electorate.

- In 1964, the British initiated political change and put the independence of the High Commission Territories on their agenda.

- A new administrative capital for the protectorate was immediately built at Gaborone.

- With the capital moved from Mafeking, South Africa, to Gaborone, the Bechuanaland Protectorate became a self-governing territory in 1965.

- Owing to the party’s effective propaganda and organising across the protectorate, the BDP swept aside its rivals to dominate the 1965 election.

- Under an elected BDP government, Khama as prime minister persisted to campaign for the independence of the Bechuanaland Protectorate while based in the newly established capital of Gaborone.

- In early 1966, an independence conference took place in London. On 30 September 1966, the Bechuanaland Protectorate gained its independence as the Republic of Botswana and Khama became its first president. In its early years of political independence, Botswana continued to rely on Britain to fully fund its administration and development.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/SouthAfrica1885.jpg/800px-SouthAfrica1885.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Kapstaaten_1905.png/800px-Kapstaaten_1905.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Australian_Army_Engineers%2C_African_Auxillary_Pioneer_Corps_and_Lebanese_workers_in_the_cutting_at_Maameltein_Lebanon%2C_1942.jpg/300px-Australian_Army_Engineers%2C_African_Auxillary_Pioneer_Corps_and_Lebanese_workers_in_the_cutting_at_Maameltein_Lebanon%2C_1942.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Flag_of_Botswana.svg/1024px-Flag_of_Botswana.svg.png

Frequently Asked Questions

- What was the Bechuanaland Protectorate?

Bechuanaland Protectorate was a British colonial territory located in southern Africa. It existed from the late 19th century until 1966, when it gained independence and became the Republic of Botswana.

- Where was the Bechuanaland Protectorate located?

Bechuanaland Protectorate was situated in southern Africa, bordered by South Africa to the south and southwest, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to the northeast, and Namibia to the west.

- Who were the indigenous people of Bechuanaland Protectorate?

The indigenous people of Bechuanaland Protectorate were primarily the Tswana ethnic group. Various Tswana tribes and communities inhabited the region.